It was almost 5 years ago in 2018 that I made these videos in a forest in Oxford and I’ve always found them entrancing. The play of the shadows across the paper has, for me, the feel of Japanese or Chinese calligraphy, as if the trees themselves were writing.

I have also, more lately, been reminded of the 2016 film ‘Arrival’ in which the writing made by the alien Heptapods has a similar look and feel.

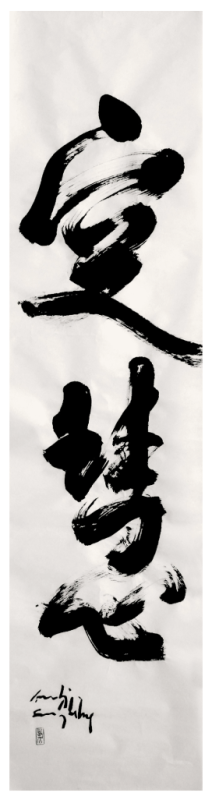

It was therefore a small step for me to begin looking at these video images as texts, ‘written’ in a language that, like the logogram above, has to be deciphered before it can be understood; a lost language belonging to a moment in time that has passed.

The ‘writing’ in these videos was made by the combination of trees, the sun and the wind, along with the person who filmed it – me. Indeed, it is the act of filming and framing these small areas of the forest floor which has rendered the shadows as something akin to ‘texts’ to be interpreted.

I’m reminded here of a passage I’ve often cited by Christopher Tilley who, in his book ‘The Materiality of Stone, Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology’, writes: “The trees ‘see’ the painter in a manner comparable to that in which the mirror ‘sees’ the painter: that is, the trees, like the mirror, let him become visible: they define a point of view on him which renders visible for him something that otherwise would remain invisible – his outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence… The trees and mirror function as Other.”

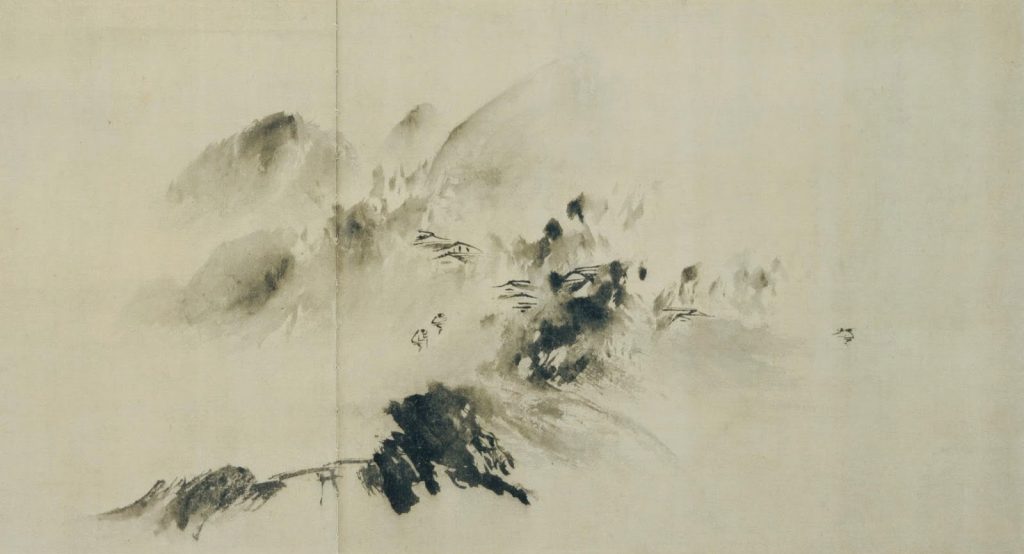

What these video ‘texts’ are describing is, I think, in part, presence, and what Tilley describes as ‘Other’. Something which would otherwise be invisible – my presence in nature – is, through the filming of the shadows, rendered visible. I must at this point bring in a passage from a book I wrote called ‘Brief Castles’ in which one of the main characters is describing his appreciation of a 13th century Chinese painting.

“Entitled Mountain Village in Clearing Mist by Yu Jian, the painting [shown below] was made all the more extraordinary on account of its age, made, as it was, around 800 years ago in the mid 13th century. This seemingly rapid work transported me to a time long gone. It revealed – much as with the Japanese haiku of Basho – an ancient and vanished moment, not so much through what it showed but how it was depicted. It was almost as if I could see the landscape before the painter himself. I could see the work as a whole (the landscape as a whole), but then, whilst picking through the gestures of the artist, evident enough in the brushstrokes, I could see the landscape as it was revealed. Yu Jian’s painting was not a painting of what was experienced, but rather the experiencing of what was experienced. It was almost as if the painting had become a painting, not of Yu Jian looking at the mountains, but of the mountain ‘seeing’ Yu Jian. It wasn’t the mountain that was made visible on the paper, but the artist himself – his presence at that moment. 800 years after his death, and Yu Jian was as good as sitting next to me. Or to put it another way, 800 years before I was born, I was as good as sitting next to him.”

The brushwork again reminds me of the videos and this line in particular resonates with what I wrote above: “It wasn’t the mountain that was made visible on the paper, but the artist himself – his presence at that moment.”

These videos are about that which is both visible and invisible; an absent presence. The trees are not in shot and all we see in the videos are the shadows cast by the branches and leaves. The moment the videos were filmed has also passed – is absent; the video pointing to the presence of the now absent film maker just as the shadows point to the trees that have also gone.

By tracing the ‘writing’ in these videos then, I am attempting, I think, to take that absence (that of the trees and the wind – the past moment as a whole) and turn it into a presence. It is a theme which has defined much of my work over the last 17 years; the idea that the past was once the present; that what has passed was once ‘now’.

We can never recover the past and by tracing the ‘texts’ in the video, I can’t recover the full ‘meaning’ of this lost ‘language’. All I can do, through the gesture of painting, is re-create that presence, which, just as with the videos, quickly becomes as much about absence, as another moment in time slips away.

I can ‘read’ the ‘texts’ and try to recover that past moment, just as I might ‘read’ an object in a museum and – by understanding how the object acts like the trees as ‘Other’ and has done with other individuals in times gone by – try to recover, though an understanding of presence, the myriad moments to which the object once belonged;

A key point here is intent. In his quote above, Tilley is describing an artist looking at the tree rather than someone seeing the tree – among many others – as they walk through the forest. This is like me intentionally filming the shadows on the forest floor as opposed to walking through the forest where the shadows play without my necessarily noticing them. Similarly, when walking through a museum we can’t help but see many of the objects on display without really looking at them. However, there are those moments when we look with intent at an object and that’s when we begin to see it as ‘Other’ and make visible (through the awareness of our own presence) what has until that time been invisible; the individual long since lost to the past.

One question I ask myself is why shadows? Why not just video the trees themselves? For one thing, there is the aesthetic quality of the shadows on the paper, but another reason is that shadows point to things beyond the frame; they take the viewer further into the world shown by the image. That is what I try to do when I look at objects in museums. I try to see the world beyond them – the world that has long gone, whether it’s a 15th century inn (as might be revealed by a fragment of mediaeval pot) or an 18th century house (hinted at by, for example, a painting).

I have explored this idea with boundaries and shadows before and described the work in previous blogs: Patterns Seeping II and Tokens and Shadows. The image below is taken from one of those blogs and is based on the fabric tokens left by mothers leaving their children in the care of The Foundling Hospital in London.