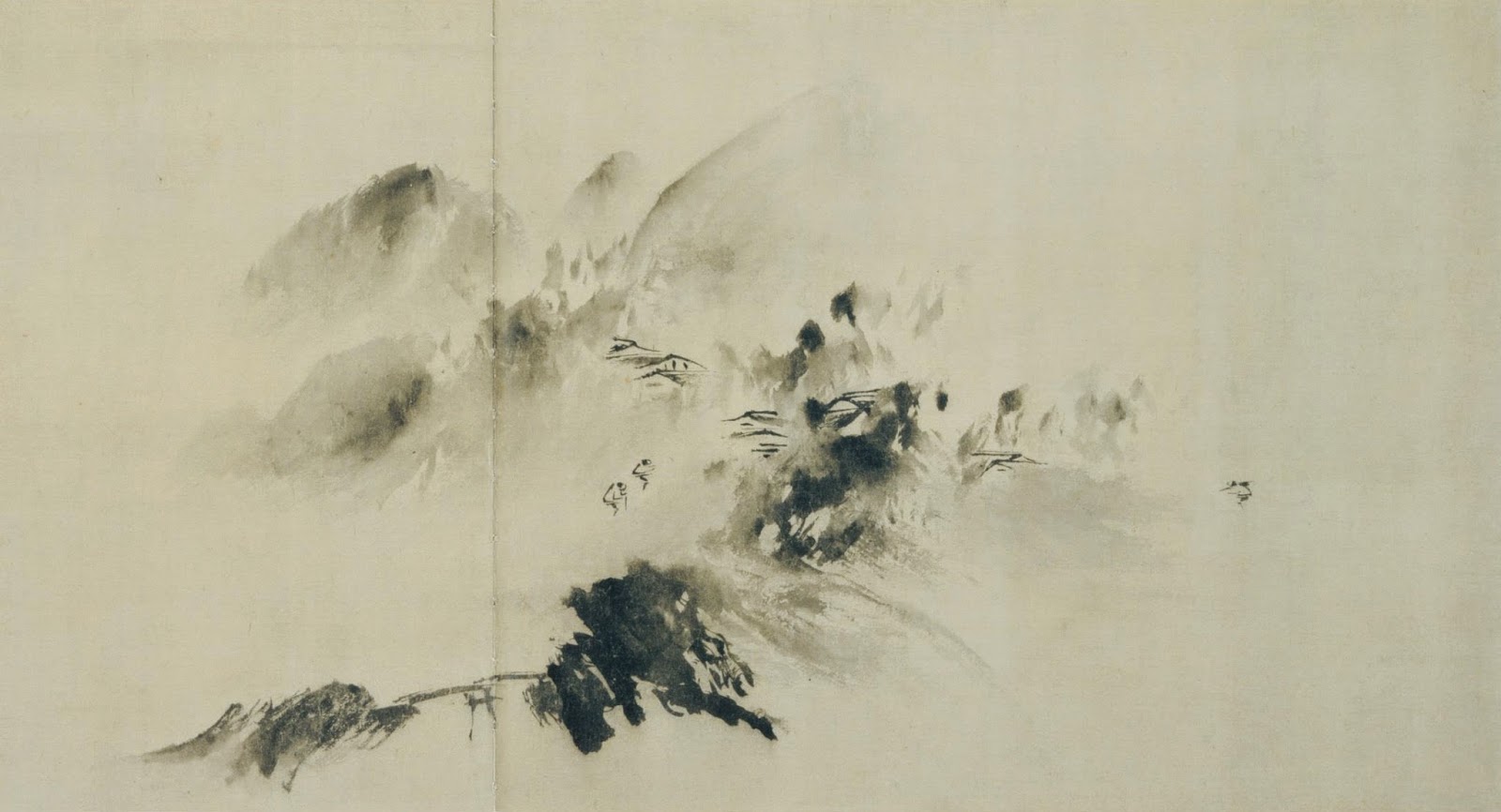

I’ve never before considered myself a fan of Chinese art but there have been times (most recently in the British Museum) when I’ve been overawed by a particular work. I refer in particular to early (11th-14th century) landscapes which move the viewer in a way one doesn’t find in the Western landscape tradition until much later on. (Why did it take so long for landscape painting to develop in the West? And why was it such a key part of painting in the Far-East so early on?) Paintings such as that below (Mountain Village in Clearing Mist by Yu Jian – made all the more extraordinary when one considers it was painted around 800 years ago in the mid 13th century), transport the viewer to a time long gone; they reveal – much as with the 17th century Japanese haiku of Basho – a moment long since past; not so much through what they depict but how it is depicted.

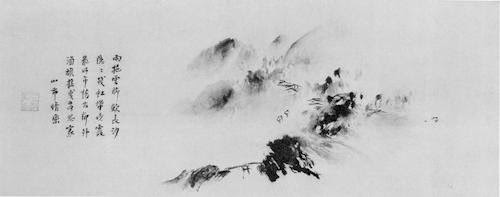

If I’ve never been a fan of Chinese painting per se, I have always admired Chinese calligraphy, which is of course, in itself, a form of painting. One can see in the full view of Yu Jian’s painting below, the text on the left hand side.

One can see here how the landscape itself becomes a kind of text, arranged not in straight lines, but in accordance with the serpentine lines of mountain paths, the drifting patterns of mist and the directions of distant sounds carried on the wind.

With works like these, it’s almost as if you see the landscape before the painter himself. We first see the work as a whole (the landscape as a whole), but then, whilst picking through the gestures of the artist, evident enough in the brushstrokes, we see the landscape as it is – or was – revealed. Yu Jian’s painting is not a painting of what was experienced, but rather the experiencing of what was experienced.

There’s a quote I’ve often used from Christopher Tilley. In his book, The Materiality of Stone – Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology, he writes:

“The painter sees the trees and the trees see the painter, not because the trees have eyes, but because the trees affect, move the painter, become part of the painting that would be impossible without their presence. In this sense the trees have agency and are not merely passive objects… The trees ‘see’ the painter in a manner comparable to how a mirror ‘sees’ the painter: that is, the trees like the mirror, let him become visible: they define a point of view on him which renders for him something that would otherwise remain invisible – his outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence… the trees and mirror function as other.”

Like the trees, the mountains share that agency; they too ‘see’ the painter’ and it’s almost as if the painting becomes a painting, not of Yu Jian looking at the mountains, but of the mountain ‘seeing’ Yu Jian. It’s not the mountain that is made visible on the paper, but the artist’s outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence.