In his book, Trees – Woodlands and Western Civilization, archaeologist Richard Hayman writes:

“…the forest provides the setting for chance encounters that take the protagonists away from their everyday lives. Woodland is the gateway to a parallel reality of the underworld, but it is also a refuge where the real world is held in limbo.”

“Woods,” he says, “are poised between reality and imagination…” They have “roots in the ground and reach up to the sky linking earth with heaven.” They “span many lifetimes” and in this sense can be seen to link the past and present too.

When I visited Auschwitz-Birkenau in 2006, it was the trees (pictured below) which most unnerved me. The way they moved in the breeze – just as they would have done at the height of Holocaust. It was this ‘everydayness’ which, for a second, enabled me to straddle past and present.

Portals to the past, these trees were once gateways to death. It was amongst these trees that victims were kept before being sent to the gas chambers nearby.

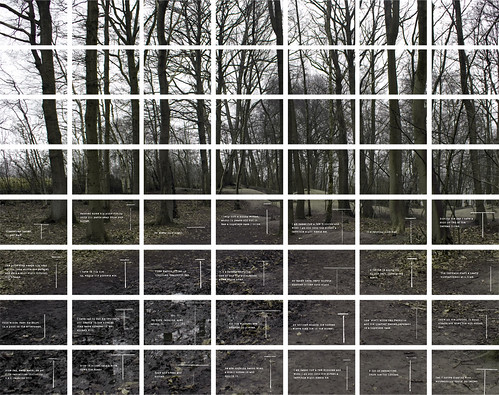

A work I created in 2009 – The Woods, Breathing – took the form of words taken from two books: one the Diary of Adam Czerniakow, the other, Pilgrims of the Wild by Grey Owl, a book which Czerniakow had read in the Warsaw ghetto.

The words were planted amongst the trees of Shotover. Some of them – quite mundane – could almost have been describing the place in which I had placed them. For example, ‘Silver birches’ pictured below.

Others, like ‘Identity Papers’ (below) called to mind the reality of Czerniakow’s world; one not so dissimilar from ours, in terms of the fact it was real.

A quote from his diary illustrates this: “In Otwock. The air, the woods, breathing.” It describes a moment of respite from the horrors of the ghetto and while we might find it hard, despite our greater efforts, to empathise with life in such appalling conditions, we can empathise much more readily with that moment in the woods.

Below is a painting by Paul Nash entitled ‘We are Making a New World.’

The trees in this landscape have been splintered by shellfire. The following extract from Neil Hanson’s book The Unknown Soldier is a vivid description of the landscape Nash is depicting.

Clearly visible on the skyline, High Wood was a long low hill, a natural strong point, the highest ground in this low-lying area. Densely forested when the fighting began, the months of incessant shelling had left it a wood in name only, reduced to a wasteland of of shell-holes, over-running with water, its trees splintered to matchwood, leaving smashed stumps barely two feet above the ground, and shattered rock and churned earth, like a sea all heaving in anger.

Below is a trench map showing various woods in an area of The Somme.

One could say the Great War was the start of the modern age; the past, in the form of dense woods had been obliterated.

The woods have grown back and walking within them, it’s almost impossible to appreciate what they were like for soldiers during the Great War. As in Auschwitz-Birkenau, it was the nowness of my being there, of experiencing the present in, for example, the moving of the trees, that enabled me to establish some kind of connection with those who had lived through such a catastrophic event. With the return of the trees comes the return of the past.