“Frontiers are lines. Millions of men are dead because of these lines.”

Georges Perec

The name Somme is, in the minds of many, synonymous with death, a byword for futile and indiscriminate slaughter. Think of the Somme and the image of men walking towards their deaths comes to mind. Think of the Somme and one date stands out above all others; 1st July 1916, the day the battle began. The battle itself lasted over four months, up until November 18th, but the 1st July is as infamous a date as any, being as it is the blackest day in British Military History. By the end of the first day’s fighting, British and Commonwealth forces had lost almost 60,000 men, with 20,000 of those killed or missing in action – a number which is almost impossible to comprehend. The exact number of casualties over the entire course of the battle (1st July – 18th November 1916) is unknown, but Allied forces lost some 620,000 men with over 145,000 killed or missing in action. Germany suffered around 465,000 casualties with almost 165,000 of those killed or missing.

These numbers are of course horrendous, but there’s always a danger that statistics such as these will only ever be numbers, rather than a single death multiplied several thousand times. Every one of those over 300,000 killed or missing in action was a son, husband or brother; an individual whose life was cut short for a small patch of ground. And we mustn’t forget the wounded whose injuries were often appalling – the result of a new type of warfare, where bodies were mauled and mangled by artillery shells, machine gun fire and shrapnel. Disfigurements and mental illness meant that even if they were lucky enough to return, many would never again lead a normal life.

Before visiting the battlefields, I recorded my thoughts on how I imagined the Somme. Drawing on old photographs, books I’ve read and contemporaneous records, I’d built up a picture – a collage of sorts – of devastated fields, cut through with trenches; craters and mud, machine gun fire and shells. I’d imagined woods reduced to spent matchsticks occupying a space on the horizon and the terrain as I saw it in my mind’s eye was almost always flat. The images themselves were silent, equivocal and without any weight or real sense of place. There was colour but like any specific detail the colours were always vague. Any imagined scene was removed from my senses. I could try to imagine the war, but of course any idea as to what it was like would – to say the very least – be well wide of the mark. I could imagine the rain, the blue sky, the smell of the grass, but still it was all divorced from my senses; an indeterminate collection of images wherein there was little sense of direction. I could try and imagine movement, but any progression derived only from a series of stills as if I was looking down a length of film found on a cutting-room floor.

Having arrived in the Somme, we drove towards our B&B, down the narrow roads which cut across the fields. The sun was setting, casting long shadows which lay down across the landscape like discarded coats and clothes. I couldn’t help but think of those who’d stood in the trenches on the morning of 1st July 1916, knowing they might never see another sunset again. For a moment, this sunset became the one they wouldn’t to see. The sunset of that terrible day.

On arriving at the B&B we found our first cemetery.

We had just over a day to explore the Somme battlefields and therefore took the ‘Circuit of Remembrance’ a route signposted with poppies which takes in the major sites of the battle. Starting at Beaumont Hamel, we travelled to Thiepval, Pozières, Longueval, Rancourt, Peronne and La Boiselle. The following morning, we travelled to Serre to see the place where, among others, the Accrington Pals suffered horrific losses on that first terrible day.

Travelling through the countryside and seeing signposts pointing the way to villages and towns such as Arras, Pozières and Thiepval, I felt a strange sensation, in that prior to visiting the Somme, these legendary names were almost fictions – places connected with a distant past found only in the pages of history. Temporal distance in some way then correlates with geographic distance, where places one has never been are like those times to which one can never go. It’s as if they are names of moments in time rather than places in another country; the past is indeed a foreign country, and yet one it seems can go there.

Of all the places we visited along the ‘Circuit of Remembrance,’ two stand out in particular; the site of the attack on Serre at what is now The Sheffield Memorial Park, and the Newfoundland Memorial Park at Beaumont-Hamel. Of course all other sites were extremely poignant, not least the Memorial to the Missing at Thiepval and the many cemeteries, all immaculately kept, which are found throughout the Somme countryside.

The first place we visited was the Newfoundland Memorial Park at Beaumont Hamel.

It’s one of the few sites in the Somme region where the ground has remained largely untouched since the end of the First World War. The trenches are still visible, for example, St. John’s Road and Uxbridge Road which once led to Hyde Park Corner and Constitution Hill; trenches now filled in beneath a field of Rape (the line of the Uxbridge Road trench has been marked in white in the car park).

The naming of the trenches has always interested me. It’s almost as if in the midst of the ruined landscape, whose pre-war character had all but been effaced, a new place was brought into being; not simply a ruin of that pre-existing world, but a new world entirely; a labyrinth of lines cut into the ground, named after streets or towns back home. It’s as if these ‘streets’, ‘lanes’ and ‘alleys’ were each a piece of the collective memory of those who fought and died there; fragments of a place called ‘home’ to which many would never return. Now of course the trenches have all but disappeared along with the men who made them, along with their individual memories. And yet they remain on maps and in books, and although the ruined towns and villages have been rebuilt, their own much older names seem to belong more to this other lost world than that before or after.

It was at Beaumont Hamel that the Newfoundland Regiment attacked on 1st July 1916, suffering as they did appalling losses. The following description is taken from the ‘Newfoundland and the Great War’ website:

“Thus it was that the Newfoundlanders moved off on their own at 9:15 a.m., their objective the first and second line of enemy trenches, some 650 to 900 metres away. In magnificent order, practiced many times before, they moved down the exposed slope towards No Man’s Land, the rear sections waiting until those forward reached the required 40-metre distance ahead…

…No friendly artillery fire covered the advance. A murderous cross-fire cut across the advancing columns and men began to drop, at first not many but then in large numbers as they approached the first gaps in their own wire. Private Anthony Stacey, who watched the carnage from a forward trench with Lieutenant-Colonel Hadow, stated that “men were mown down in waves,” and the gaps cut the night before were “a proper trap for our boys as the enemy just set the sights of the machine guns on the gaps in the barbed wire and fired”. Doggedly, the survivors continued on towards The Danger Tree.”

The ‘Danger Tree’ still stands, and standing there today, looking at the sheep laying around its base, it’s hard to imagine the scene at that same place 96 years ago.

Like many who’ve read about the Somme, I was aware how close the opposing armies were to one another – at least in terms of stats – separated as they were by the void of No Man’s Land, but it was only in this place that the distance was made startlingly apparent; it was hardly any distance at all. Entering the memorial, one can see the British front lines. A leaflet guides you around and suddenly, you find yourself looking back from the German front line towards where you entered, a distance which is all but a few minutes’ walk away. And in between is a patch of ground, much like any other you might have seen before but upon which thousands lost their lives.

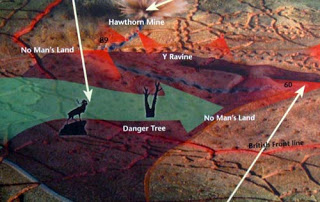

The following images show the Caribou Monument to the Newfoundland Regiment (shown on the map above) which stood at the British Front Line. The Danger Tree is that shown above which marked the furthest many men managed to get. The Y-Ravine is behind the German Front Line, the trenches of which are also shown below.

Of course it goes without saying that in 1916, the ground would have looked very different. Pockmarked by shells, cut through with trenches running on for miles and covered with swathes of barbed wire it would have presented advancing troops with considerable difficulties even without the horrors of enfilading machine gun fire and pounding artillery.

As far as can be ascertained, 22 officers and 758 other ranks were directly involved in the advance that day. Of these, all the officers and around 650 other ranks became casualties. Of the 780 men who went forward about 110 survived unscathed, of whom only 68 were available for roll call the following day. To all intents and purposes the Newfoundland Regiment had been wiped out, the unit as a whole having suffered a casualty rate of approximately 90%.

It goes without saying that as tourists today we can never imagine what it was like to be a part of this battle, not that we should be deterred from trying. Even so, one can appreciate things which sharpen the focus of any prior knowledge of the war and in particular any images which one might have imagined beforehand. I’d read about the attack on Beaumont Hamel in a book by Peter Hart and had imagined a vague collection of ‘ambiguous stills’ with which I did my best to appreciate the experiences of those who suffered the appalling violence of that first day. But standing in the middle of what had been No Man’s Land, with the British Front Line to my left, beside the Newfoundland Caribou Memorial, and the German Front Line to my right – just behind the memorial to the 51st Highland Division – I was struck by how small the battlefield, at that position, was. As I’ve said, if this was any place in the countryside, it would constitute nothing more than a small part of a short walk, but in 1916 it was a great advance, in the pursuit of which, many thousands lost their lives.

There is a tendency at sites such as this, or rather in associated museums (for example that in Ypres) to create recreations of battles with sounds effects, waxworks, lighting effects and so on. For me, such recreations do nothing other than turn history into fantasy. They push history – which already borders on fiction (in that it can only be imagined) – deeper into the world of make-believe. Recreations serve no other purpose than to ‘entertain’ and certainly do little by way of justice to memory of the men who fought there. It’s much better to be in a place, to hear the birds and see the trees… they might not be shells or machine guns, but they are real all the same.

I must admit I could have stood there in ‘No Man’s Land’ for hours, collecting together what I knew of the war and what I could glean from the guide and anchoring it to the reality of the world by which I was surrounded. What I could really appreciate here was the terrain, not only the pock-marked surface, but the level of the ground which, superficially at least, appeared quite ‘flat’. Certainly, if one was out walking, one wouldn’t think it was particularly steep or hilly. However, from the point of view of those who left the British Front Line to attack the Germans, one could see what they were up against. The ground rose just enough to leave them exposed, while at the same time affording the German army at least a degree of shelter. Indeed, something which I found myself coming to understand in the Somme, were the subtle shifts of the terrain and how such changes, visible to the individual eye, shaped the war as a whole and determined the fates of so many hundreds of thousands of men.

The image below is taken in what was No Man’s Land. The Y Ravine Cemetery is on the right. Over the ridge in the distance is the German Front Line.

Over the course of the last few years, ever since my visit to Auschwitz, I’ve tried to understand what it is about being in a particular place that makes knowledge of a past associated with that place so much more compelling. It seems obvious that it should be the case, but why? I can watch countless DVDs about the Somme for example, view masses of photographs, read the testimonies of those who fought and look at the lists of the names of the dead. But only by standing there, in the middle of a field (upon which sheep were grazing) did the full horror make itself known.

I felt exactly the same thing at the Sheffield Memorial Park, situated on what was once the British Front Line between ‘Matthew Copse’ and ‘Mark Copse’ near the village of Serre. It was from here that an attack was made on what was then a fortified village by, amongst others, the Accrington Pals and Sheffield City Battalions, again on that infamous day, 1st July, 1916.

Again, staring ahead towards the Queens Cemetery, behind which the German Front Line would have run, one could see just how close the two sides were to one another. One could also read the terrain and see the advantage the Germans had when facing the approaching army. As a result therefore, one could also see just what the soldiers of the Pals Battalions were up against, even without the horrors of machine guns and artillery.

Again I have to stress, that we can never fully appreciate what the men who climbed from their trenches faced that fateful day. But as with my experience at the Newfoundland Memorial, I found that in looking towards where the German lines would have run, across the field over which the soldiers would have walked, the horrors of which I’d read became much clearer. I couldn’t see the guns of course, or the artillery and barbed-wire. I wasn’t walking into a hail of bullets with shrapnel flying from shells bursting all around me. But there in the tranquility of the present day, where one could hear the birds, I’d brought with me to that place, the whole of my existence – my past – and that was something at least I had in common with the brave men who fought there.

In La Boiselle, one can find the Lochnagar Crater, caused by a huge mine detonated at 7.28am on 1st July 1916. Containing 24 tons of explosives, it was at the time the largest ever man-made explosion.

At 300 feet in diameter and 70 feet deep, the crater is still the largest caused by man in anger. Again, like the various battlefield sites, it’s a tranquil place, in stark contrast to the violence from which it was created. And yet, although one can’t hear the noise, one can see it in the vast space left in the ground. The sound has left a footprint; it’s become physical, just as sounds remain in the pock-marked battlefields found across the Somme.

In some respects, this idea of a ‘sonic footprint’ is akin to that of people leaving a trace on paths, roads, tracks and other lines found in the landscape. The trenches for example – those which one can see today – are not as they were in 1916 (i.e. they’re not as deep and are grown over with grass) but they are lines created by people many years ago. They might not call to mind a sound in quite the same way as the Lochnagar crater, but they’re nonetheless records of actions and movements.

In his book, ‘Lines, A Brief History’, anthropologist Tim Ingold writes that human beings, ‘leave reductive traces in the landscape, through frequent movement along the same route’. He considers this in light of the etymology of the word writing (derived from the Old English term writan – meaning to incise runic letters in stone) and surmises that human beings somehow ‘write’ themselves in the landscape. Henri Bergson wrote that our whole psychical existence was something just like a single sentence. I believe,’ he said, ‘that our whole past still exists.’ The whole past could be said to exist, upon and within these trenches, as ‘sentences’, ‘written’ in the landscape by men almost 100 years ago.

These lines can also – metaphorically speaking – be thought of as magnetic tapes, where as we walk, we record our presence; where what we see, hear, touch etc. at any given moment, is analogous to the recording head of a tape-player arranging the magnetic particles so as to record the sound or video image. Equally, when we walk down a particular street, path or track, we simultaneously play-back previous recordings, those laid down by people long since lost to the past and the battlefields of the Somme are a perfect place to illustrate this point.

At the battle for Serre on that fateful day – 1st July 1916, hundreds of men lost their lives on the ground between the village and the memorial where we were standing. The weather on the day of our visit was mixed, but mostly dry (the battle took place on a beautiful summer’s day). There were patches of blue sky and the odd cloud. Looking ahead, I could see the lie of the land. I could see the distance, the village of Serre and behind me the trees of the copse. I could hear the birds and feel the ground beneath my feet. Imagine then, that as I walked, the things I saw were somehow recorded in the ground upon which I was walking: the position of the sun, the colour of the sky, the sound of the birds and the distance. As a record-head receives information and translates it onto tape, so metaphorically, my body was doing the same.

Of course, recording-heads don’t just record, but play-back all that’s previously been recorded. Again we can think of the ground as being crossed by many lines and that along every one of those lines are hundreds of ‘recordings’ left by those who went before us. We can imagine that what they saw, what they heard and what they thought were all translated into the ground upon which they walked.

It was Bill Viola who said that ‘we have been living this same moment ever since we were conceived. It is memory, and to some extent sleep, that gives the impression of a life of discrete parts, periods or sections, of certain times or highlights’. If we think of the lines the soldiers left behind, lines which stopped abruptly in No Man’s Land, we can imagine them leading all the way back to the time they were born.

These long, individual lines are of course impossible for us to imagine in their entirety, but on sites such as the battlefields at Serre and Beaumont Hamel, where the lines of trenches can still be seen and where No Man’s Land stretches out ahead, we can be sure at least of seeing a small part. By following these fragmentary lines, our bodies in a very small way mirror that of the soldiers. Again I have to stress the words very small way and again make it clear that we can never know what it was like to experience what they did.

When we walk down the line of a trench, the gestures of our bodies are bound in some very small way to mirror those of people caught in the midst of war. When we look at the sky, down at our feet, turn our heads left or right, we can assume that an aspect of the way our bodies move is almost a mirror-image of those who went before us. We can imagine then, that when we plant a footstep, the way our body moves, what we see around us is akin to the idea of our bodies playing back that which has been recorded in the ground; the ground determines how we move – determines the shape of our body; thus we empathise kinaesthetically with those lost to the past.

These lines, as I’ve said, are only fractions of the total line carried by men into battle, i.e. the total span comprising the entire geography of their lives. But history is full of holes, and the gaps have holes of their own.

History tells us only a little about the past. It gives us the outline whereas the rest is all but missing. The history of an event, as told in a book, has a beginning, a middle and an end, but of course in reality the past is never like that. Historic events are about the people involved, many of whom are missed out altogether. For George Lukács, ‘the “world-historical individual” must never be the protagonist of the historical novel, but only viewed from afar, by the average or mediocre witness.’ In other words, those historic events written about in books, are best discovered through the eyes of those who are missing from the text, people who at best are either given the epithet ‘mob’ or ‘masses’ or are bundled into numbers and tables of statistics. It’s through the eyes of these people that I want to see the past.

To consider this a little further; in the film Jurassic Park, the visitors to the Park are shown an animated film, which explains how the Park’s scientists created the dinosaurs. DNA, they explain, is extracted from mosquitoes trapped in amber and where there are gaps in the code sequence, so the gaps are filled with the DNA of frogs; the past is in effect brought back to life with fragments of the past and parts of the modern, living world. This ‘filling in the gaps’ is exactly what I have done throughout my life when trying to imagine the past and it’s just what we do in terms of the fragments of lines upon which we can kinaesthetically engage with people lost to the past. Where there are gaps we use our own lives to fill the holes and thereby understand that those who died in places like the Somme, were people just the same as ourselves.

Something else which plays a key role in interpreting landscapes such as those at the Somme is something which we might describe as ‘Embodied Imagination.’ We all at some point in our lives try to imagine the past whether through photographs, paintings or literature, but what we imagine always comprises snapshots, static images animated to some degree by our imaginations. It’s exactly how I described my thoughts on the Somme before my visit.

“Before visiting the battlefields, I wanted to record how I imagined the Somme. Old photographs, books and contemporaneous records all made a picture – a collage of sorts, comprising devastated fields, cut through with networks of trenches. Craters and mud; machine gun fire and shells. Woods reduced to spent matchsticks occupying a space on the horizon. The terrain as I’d imagined it was always flat and the images themselves silent, equivocal, without any weight or sense of place. There was colour but like any specific detail it was always vague. Any imagined scene was removed from my senses. I could try to imagine the war, but of course any idea as to what it was like would be well wide of the mark to say the very least. I could imagine the rain, the blue sky, the smell of the grass, but still it was all divorced from my senses; an indeterminate collection of images wherein there was little sense of direction. I could try and imagine movement, but any progression derived from a series of stills as if I was looking down a length of film found on a cutting-room floor.”

In his book ‘The Materiality of Stone: Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology,’ Christopher Tilley writes:

“At the basis of all, even the most abstract knowledge is the sensuous, sensing and sensed body in which all experience is embodied: subjectivity is physical… The body carries time into the experience of place and landscape. Any moment of lived experience is thus orientated by and toward the past, a fusion of the two. Past and present fold in upon each other. The past influences the present and the present rearticulates the past.”

In a ‘Phenomenology of Landscape,’ he writes: “Knowledge of place stems from human experiences, feeling and thought.”

We could say therefore that knowledge of the Serre battlefield, for example, stems from ‘human experiences’ (the experiences of those who fought in 1916), ‘feeling’ (my own kinaesthetic experience of the battlefield in the present day) and ‘thought’ (my embodied imagination where my knowledge of past human experience is animated by my own kinaesthetic experience). Knowledge of a place is both geography and biography, of both the place and the individual.

Again, Christopher Tilley’s work is useful here. In his book, ‘Body and Image,’ he writes:

“What the body does in relation to imagery [landscape], its motions, its postures, how that imagery [landscape] is sensed through the fingers or the ear or the nose, as much as through the organ of the eye, actively constitutes the mute significance of imagery [landscape] which to have its kinaesthetic impact does not automatically require translation into either thoughts or meanings. The kinaesthetic significance of imagery [landscape] is thus visceral. It works through the muscles and ligaments, through physical actions and postures which provide affordances for the perceptual apparatus of the body in relation to which meaning may be grafted on, or attached. Meaning is derived from and through the flesh, not a cognitive precipitate of the mind without a body, or a body without organs.”

The ‘perceptual apparatus of the body’ as described by Tilley is akin to what I’ve described as my kinaesthetic experience of the battlefield. ‘Meaning’ can then be ‘grafted on’ or ‘attached’, where that meaning is my knowledge of past human experience. The whole is what I’ve described as ‘embodied imagination.’ But we must be careful not to reduce experience down to a mind/body dualism. The mind is not divorced from the body, neither is the body separate from the mind. ‘Consciousness is corporeal.’

I mentioned earlier the names of the trenches; the fact that for four years, a strange, new and violent place was imposed upon a peaceful agricultural landscape; how it’s almost as if the names of the trenches were fragments of the collective memory of those who dug and occupied them. Today, when we walk along what remains, we engage kinaesthetically with those who knew them during the war and we carry with us the entire geography of our existence, stretching back in a line to the day we were born. In effect, we impose – just as we’ve done throughout our lives – our own world upon that which already exists. “In a fundamental way,” writes Christopher Tilley, “names create landscapes” and in a sense, the names of those we have known, whether throughout our lives or for a few minutes are mixed with the names of streets, cities and buildings, to make a landscape unique to us as individuals. The landscape of the Somme, in the physical present or in books and maps has been created not only by the names which existed prior to the war, but by the names of the trenches, fortifications and not least the names of everyone who fell here.

Inevitably in a place such as the battlefield at Serre where so may men fell on that small patch of ground, one’s thoughts will turn to death – the literal end of the line. In an interview in 1979 with Frank Venaille, writer Georges Perec was asked: “…don’t you think that… the determination to work from memories or from the memory, is the will above all to stand out against death, against silence?”

If we can empathise kinaesthetically with the lives of the men who fought, it’s almost inevitable that we will somehow engage with their deaths which inevitably means a contemplation of our own, and in that sense, the fact that we can then walk away means that to some extent we do indeed stand out against death and silence.

Death is at its most visible in the cemeteries and monuments of the Somme. The landscape is covered with hundreds. Immaculate and maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, they are strangely beautiful places wherein one’s breath is always taken away by the row upon row of white headstones. It’s only here the scale of the slaughter becomes apparent. Some headstones have names, many – where names are unknown – have just the words A Solider of the Great War. Often the date is familiar, coinciding with the start of a phase in the battle, July 1st 1916 for example. But many men too vanished altogether and over 72,000 of these men are commemorated on the Thiepval memorial to the missing.

In some respects, by being in the places where they fell, by walking the lines of the trenches and through ‘reading’ or ‘playing-back’ ‘recordings’ in the lines which cover the Somme as I’ve described above, we are, kinaesthetically, remembering the missing and all who never returned home. People are places and places are people. Remembrance is not an act solely of the mind, but of an embodied imagination.