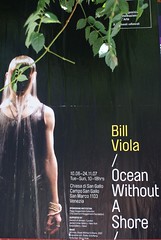

For some time I have wanted to visit the Biennale, and, finally this year, I went. To be honest, I had little idea what to expect, or what – from a ‘professional’ perspective – I would gain, but my hopes were raised when, having left our hotel, we saw the following poster:

Admittedly this was a fringe event, but it promised much. I last saw Bill Viola’s work in May this year, in Warsaw, and was blown away by it. He’s an artist who interests me a great deal, not just through his exhibited works, but also through his writing. So, on a hot and glorious day, we made our way to the Chiesa di San Gallo, a small and somewhat unassuming fifteenth century church, a stone’s throw from St. Mark’s Square.

Inside it was dark. On three altars, three large, flat screens were placed, one in front and two either side of those who stood or sat watching near the entrance. There was a stillness inside, emphasised by the sonic aspect of the work as well as by the coolness of the interior, a quietude augmented by the contrast with the heat and the light outside.

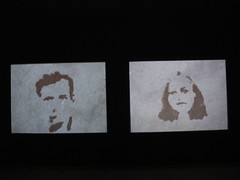

At first I thought there was something wrong with two of the screens, as the pictures shown on both of them were monochrome, blurred and rather grainy, much like an image one might see through an infrared camera. The screen directly in front however, showed a figure, beautifully lit and filmed as one would expect from Viola. Of course the point soon became clear.

Before the monochrome figures was a wall of water which one could not quite discern except for the occasional highlights at the bottom of the screen where the water caught the lights. Slowly, again in Viola’s inimitable style, the figures behind the water (always shown in isolation) walked toward us, towards the mysterious screen of water. Then at last they broke through, their limbs shrouded in a halo-like light as the water became visible around them.

The figures (of which there were several) then stood for a moment, before – after varying periods of time – they walked back through the screen of water to become monochrome, fuliginous shadows; versions of what they had just that second been.

This was a work, whose meaning was emphasised and expounded by its location. It could quite easily work in isolation, in a gallery (as was the case in Warsaw) for example, but here, in the church, it became a different piece altogether; the church was as much a part of the piece as the images played on the screens; indeed, the work’s meaning came as much through it’s ancient interior, (through which countless generations have passed in consideration of life and death and life after death and who are now themselves memories held by the church) its stones and its statues, as through the power of technology. As one looked at the ghosts behind the invisible walls of water, one could imagine the ghosts of all those who’d once sat where we were sitting. And when the figures emerged and returned to the depths, thoughts of one’s own mortality could not be ignored. More can be seen at the official website, www.oceanwithoutashore.com.

The next day we made our way to the Giardini to see the pavillions of the various participating countries and to see what, along with Bill Viola, was on offer. It says something about the art that we soon had a leaderboard (as if this was a Eurovision event) and even more, that for much of the trawl through the Giardini we had only a first and second place. Nothing warranted a third, although the battle for the wooden spoon was intense (won jointly in the end by Canada and the quite appalling German contingent).

For me, the best piece by some way was to be found in the Polish Pavillion, represented by Monika Sosnowska.

This was one of the few pieces in the whole exhibition which (like Viola’s fringe work) considered the space in which it was displayed. The architectural form, a sort of prefabricated structure had been bent and twisted so as to fit into the space in which it was shown. It had it seemed been brought to its knees and brought to mind an exhibition we had seen in Poland a few months back concerning the housing developments of the communist era, in which it wasn’t so much the structures themselves which were crushed and forced to fit a space, but humans themselves. The structure also reminded me of my own work as regards my drawings, and so I saw this almost as a physical, three dimensional drawing.

Spain came second and Russia third with the USA in fourth. I know it cheapens the whole event to reduce art to winners and losers, but then, such was the overall standard of the work it was hard not to see it that way. As for the British Pavillion… the less said the better.

Later that afternoon we took in the Arsenale, the quarter mile interior beneath which, art is reduced even further by casual and indifferent glances, to side shows and decoration. Admittedly the space is very impressive (how often is that phrase used as a means of justifying an otherwise mediocre exhinition) and there were moments when one felt glad to be there.

Oscar Munoz’s Memorial was particularly poignant, and Yang Fudong’s series of films (parts 1 to 5 of ‘Seven Intellectuals on the Yellow Mountain’) especially beautiful.

But aside from these there was little else to get excited about. The question, fundamentally, is this: how should art be seen? Or to put it another way, how best is it viewed? With Viola, the work was in its own space and its power was enhanced by the content within the church and the light and life outside. With the Biennale, in the Pavillions and the interminable Arsenale, art became like any word repeated over and over again; in the end (actually some time before the end) it lost its meaning completely.