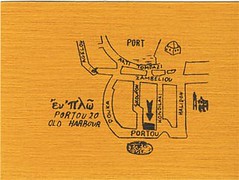

It was in the small square, at southern end of Kondylaki Street, where we met two brothers, coaxing as best they could, passing tourists into their restaurant. “My brother and I are having a party,” they told us, “at 7.30.” They handed us a card. “You’re nice people, where are you from?” They’d asked the same question, albeit more pointedly (and with a heavy dose of irony) to those who’d ignored their advances. England, I said, and Monika, from Poland. Funny how when speaking English to foreigners, I do so with an accent; one which I presume is something akin to – as in this case – the Greek way of speaking. I’d done as much in Spain a few weeks back, ordering a beer as if I was Speedy Gonzalez. “Ah, Poland! Where in Poland? Krakow? Warszawa? Katowice? Czestochowa?” Warszawa, came the reply. “The best!” one of the brothers replied, with acute comic timing; it was clear they’d been doing this for quite some time. “It starts at 7.30 and…” one added, as an aside, but yet, with a certain flourish, “I assure you, my mother and my sister are in the kitchen…” As if we needed such assurances.

Having already walked around much of Chania, I had the impression that aside from the 15th century lighthouse, many of the town’s landmarks, or architectural points of interest, somehow lurked around streets such as this one. They stood in corners, perched above the roads (or lay below ground level) stealing themselves away in shadows, rather than standing out as buildings often do, waiting like dressed up grandparents for a visit. This is certainly not a criticism (far from it), and there are of course exceptions to this – for want of a better word – rule. But generally speaking, Chania’s visual history is there to be found rather than simply observed. Of course, no building in any town or city gives up its secrets through simple observation; one must enter into some sort of a dialogue. But in the way in which a building might give up its secrets, so Chania gives up its buildings.

The history of the town is as interesting as it is often tragic, and the scars of war and conquest are manifest in its palimpsestic array of buildings, many of whose origins date back to the Venetian era (13th to mid 17th century). It is the site of the ancient Minoan settlement of Cydonia (evidence of which can be seen in the Kasteli district in the Old Town), and has been ruled successively by Byzantines, Arabs, Ventians and Ottamans, who overran the city in 1645. Finally, in 1941, the Nazis took control and another tragic page in Chania’s history was written.

Walking around the town, we found evidence of this tumultuous past in churches turned into mosques and mosques turned back into churches; Islamic arches filled in and plain windows set within the stones. I’ve always harboured an interest in blocked up doors and windows, and here in Chania there were many examples. And this is what I find so fascinating about the town; the fact that ruins are not isolated but are used again in other buildings, that successive architectural values give rise to conflated, unique, and idiosyncratic styles; that where one regime follows another, the past is not torn down, but is modified (one is reminded here of recent debates surrounding communist buildings in post-communist countries).

The Janissaries Mosque for example on the western harbour, built in 1645 is now an art gallery, and on its facade one can still see portions of Arabic reliefs – scripts carved from out of the stone. The calligraphy is worn and whispering, yet its presence is a clear reminder of the past. And all around Chania, it is these shards which pierce the consciousness of the traveller; Venetian windows and doorways plugged into tumbledown houses appear like childhood memories from nowhere, and one realises that Chania is not a town of buildings at all, but rather one constructed entirely of fragments. And such is the the number of fragments revealed to those who walk the streets, I found myself – as a typical tourist – taking numerous photographs. My camera was readied as if I was on safari, ready to capture an exquisite Venetian architrave, which might, at any moment disappear back into the shadows. I remember writing a while back, a novel set in my home town Oxford, where the young protagonist observed through an iron gate, one of the last remaining Bastions of the old city wall. “St. Cross was the daughter church of St. Peter in the East and was situated not far from that church in a street of the same name. It was approached by Longwall Street, towards the end of which, just before the junction with Hollywell and St. Cross Road, Adam’s pace slowed in anticipation of the gate through which could be glimpsed a remnant of Oxford’s mediaeval past. It was one of his favourite monuments, but no matter how contrived and deliberate his steps, the lone bastion of the old city wall seemed to fall from sight as if glimpsed from a passing car, as though no mortal eyes could frame it for longer than the time it took to blink. It was as if through the bars, the centuries passed still lingered, appearing in a space built for a second.” This is how I felt, when finding evidence of the past in these remnants of windows and doors. I would stand and try to build the past around them, that from which they were – for a few seconds at least – conspicuously estranged. But no matter how long I looked, for example at the window below, my gaze could never do justice to the scale of the past behind it.

Even when looking at the photographs, I find the same thing applies, and I’m reminded of a quote from Proust, as discussed in a text by Samuel Beckett: “But were I granted time to accomplish my work, I would not fail to stamp it with the seal of that Time, now so forcibly present to my mind, and in it I would describe men, even at the risk of giving them the appearance of monstrous beings, as occupying in Time a much greater piece than that so sparingly conceded to them in Space, a place indeed extended beyond measure, because, like giants plunged in the years, they touch at once those periods of their lives – separated by so many days – so far apart in Time.” These elements, these architectural shards, are like parts of those same-said giants, parts of limbs touching the present day. We cannot observe with one look the beings as a whole, we can only walk and see in pieces what constitutes the sum, a sum which can only ever be imagined.

I’d thought, whilst walking around Chania, how with every step it seemed to change, as if one were walking through a huge kaleidoscope – a image enhanced by the colour in the streets; the kitsch fodder for tourists, the pink hues of the closing day and the swarms of people, emerging to devour the night, flitting about the myriad lights. The town’s character is revealed through whatever fragment it chooses to present the viewer, at whatever time: a window’s architrave, a decorative lintel, an old vaulted ceiling in one of the many restaurants. I could imagine a mass of giants, writhing beneath the cover of Chania’s single facade, itself like a blanket – a patchwork quilt by which the past is covered.

On the bus to Heathrow, just the week before we found ourselves in Chania, I had been considering my work on the Holocaust and considering the question which so many ask me, ‘why are you interested?’ There is, I have since realised, a reason why, but in the process of finding the answer, I found myself considering other traumatic events and in particular the places where these events were played out, whether Auschwitz-Birkenau, the battlefields of World War 1 or a single cell in the Tower of London. Recently too, I’ve been watching Claude Lanzmann’s ‘Shoah’ and whilst listening to the testimonies of survivors, I thought of those places I had visited; Auschwitz-Birkenau, Majdanek and Belzec. Listening to (and indeed watching) the testimonies of those who perpetrated such crimes (‘may I takes notes?’ asks one, as if learning the facts of the crimes for the first time and thereby denying his own involvement), I found it hard to see, in the faces of men who looked like any other grandfather, the face of the monsters they were (excepting Josef Oberhauser, interviewed by Lanzmann in a Berlin bar). The truth is – and this is what makes the Holocaust all the more terrible – ordinary people, who outside of war would, in all likelihood, have led ordinary lives, did in war, unspeakable things. Likewise, ordinary places became sites of gross inhumanity, trees became soldiers, as if beneath the surface, there exists a poison, which surfaces in history and debases everything and everyone it touches, disappearing to leave the world silent, the victims dead and perpetrators old, old men, hoping that age might rob them of what they’ve done.

Walking up Kondylaki street, away from the harbour, we saw a sign for the the Etz Hayyim Synagogue. We followed the sign, and as if the giants moved beneath the surface of Chania’s long facade, a doorway opened up to us.

The free literature explained how: ‘the synagogue was reconstructed under the aegis of the World Monuments Fund in New York and the Central Board of Jewish Communities of Greece…’ and that ‘…while committed to its Jewish character Etz Hayyim is also sensitive to the multi-ethnic and religious needs of our times and its doors are open to provide a haven for all persons seeking a place of spiritual repose and regeneration.’

Indeed it was a place of great tranquility; a peace at odds with the past, and the sad history of those who once prayed there.

Turning back to the pamphlet supplied by the synagogue, I read the following section, entitled ‘The 2nd World War and the Jews of Hania – 1941-1944’. It read: Suddenly, just before dawn on the 29th May 1944, the entire area in which the Jews lived was blocked off by trucks and loudspeakers ordered the Jews out into the street. They were not allowed to take anything with them and were assembled at the south end of Kondylaki Street in the small square and in the square adjacent to the harbour to the north. Within an hour they were driven by trucks to the prison of Ayas not far from Hania. The Jewish Quarter was immediately looted – first by the soldiers. In the late afternoon they synagogue of Etz Hayyim was stripped of all its religious artefacts and left to be rented by squatters. After almost two weeks of imprisonment at Ayas, with little food and no changes of clothes, the Jews of Hania were loaded onto trucks and driven to the east of the island to Herakleion. The official count is that 265 men, women and children arrived there on the 9th June and were put on board a converted tanker called the Tanais that set sail for Athens that evening at 8.00. Along with them were some 600 Greek and Italian prisoners of war. At 3.15am on the morning of the 10th June the ship was sighted just off the island of Milos by a British submarine and immediately given a torpedo broadside that broke the ship apart. All who were aboard were drowned. Had the ship arrived in Athens the Jews on board would have been sent by cattle-cars to Auschwitz-Birkenau for immediate gassing and cremation which is what had already happened to the Jews of Salonika and elsewhere in Greece. 94% of the Jews of Greece perished in the ‘Final Solution’ of the Nazis.

It was hard to imagine, walking back up this street and around those of the old Jewish Quarter, how such a thing could have happened here. But it did.

“You are nice people…” one of the brothers said. He was again being sarcastic. The group of tourists had declined his advances and so he fixed his eyes on a female member of the party, and drew his hands down, as if to trace her curves. He looked at me and winked, nodding in her direction. I smiled and walked on.