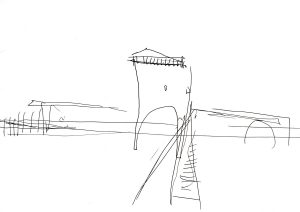

The journey into my own past and that of my ancestors began following a visit to Poland in October 2006, during which time I visited Auschwitz-Birkenau. There are, as far as I’m aware, no familial connections with the camp or indeed with the Holocaust, and yet, after visiting Auschwitz and other camps, such as Majdanek, Belzec and Natzweiler-Struthof, I began to search for my own heritage – a search which has enabled me, in some small way, to resolve what I can only describe as my confrontation with History at the site of the infamous death camp.

One of the many difficulties facing the visitor at Auschwitz-Birkenau, apart from the sheer, overwhelming, tangible horror of the place (its physical presence, the documentary evidence and the exhibits of possessions and other human artefacts) is the enormous numbers with which one is confronted. How can one possibly imagine 1.1 million dead? How can one, amongst that mountain of disappeared people, find the individual to whom one might, in some small way, relate? After all, with the exception of a relative few who wrote about their experiences (Anne Frank, Primo Levi, Filip Muller and so on) all that remains of millions of people are mountains of shoes, mountains of ash, lists of names, or maybe nothing at all.

So having stood upon the Ramp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, and having walked away, I wanted to explore my relationship – as an individual – with the past, with History itself, and so I began to mine my own past; the mountain of anonymous people I call my ancestors.

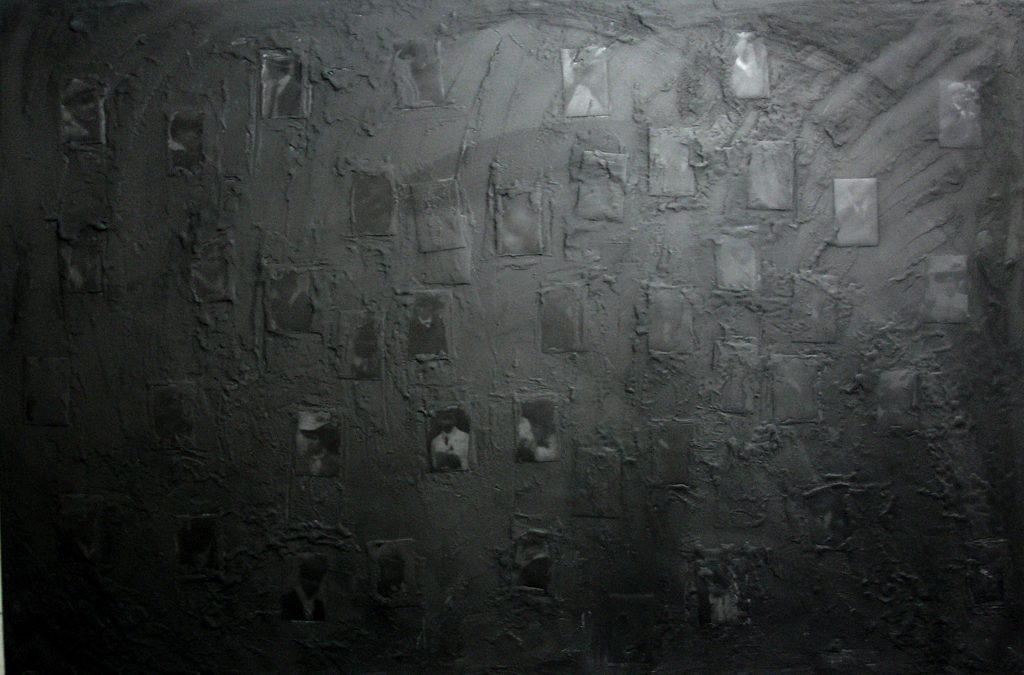

I joined the Ancestry website and soon began to build my family-tree; great-grandparents, great-great-grandparents, great-great-great and so on, tracing all four lines to the end of the eighteenth, beginning of the nineteenth centuries. In all I amassed over 300 names, the vast majority of whom no-one knew; they were names and nothing more. But as these names – these pieces – were placed in the puzzle, as relationships were re-established so they began to live again. Movements between counties and countries, across the UK, from one generation to the next, augmented this sense of my ancestors’ reawakening and soon I began to see the tree as my own geographic biography; I was able to map my own coming-into-being directly onto the landscape.