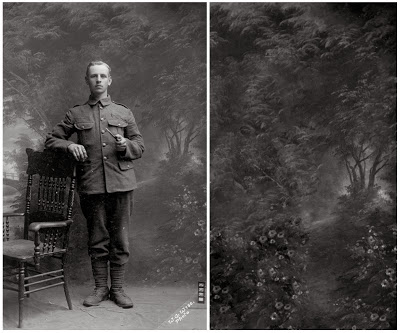

The image below (that on the right) has been made as part of my research towards creating landscapes based on the backdrops of WWI soldier portraits.

The Keening Landscape

The First World War: this young soldier would have played his part; perhaps one of the nearly 900,000 British men killed in action. Or one of the over 1.6 million wounded. But there is nothing in the backdrop or prop that points us towards that tale. Just the costume.

So what story does the scenery tell us? A soldier stands in a landscape; an idyllic world seemingly untouched yet threatened by a war in which the soldier has yet to play his part. (Or rather, the war has yet to play a part in the soldier’s life: an important distinction, for if the story or ‘play’ is History, then this soldier’s part would be a minor one. Imagine a vast stage, filled with hundreds, maybe thousands of actors. Most of them would say nothing, remaining part of the anonymous ‘chorus’ (exiting and entering the stage) leaving the lead actors, playing the parts of named politicians and Generals, to speak any lines. Yet of course, in his own life story, this soldier would play the lead. It would be as if towards the end of the ‘play’, one of those hundreds or thousands of extras making up the chorus, would step forward and begin to speak.)

Quotes from ‘Trees’

Trees – Woods and Western Civilisation by Richard Hayman

“…the forest provides the setting for chance encounters that take the protagonists away from their everyday lives. Woodland is the gateway to a parallel reality of the underworld, but it is also a refuge where the real world is held in limbo.”

“Woods are poised between reality and imagination…”

Trees

In his book, Trees – Woodlands and Western Civilization, archaeologist Richard Hayman writes:

“…the forest provides the setting for chance encounters that take the protagonists away from their everyday lives. Woodland is the gateway to a parallel reality of the underworld, but it is also a refuge where the real world is held in limbo.”

“Woods,” he says, “are poised between reality and imagination…” They have “roots in the ground and reach up to the sky linking earth with heaven.” They “span many lifetimes” and in this sense can be seen to link the past and present too.

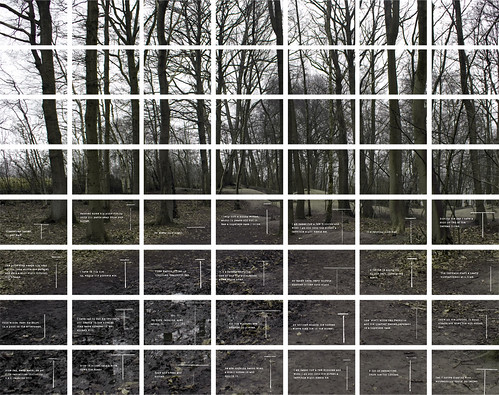

When I visited Auschwitz-Birkenau in 2006, it was the trees (pictured below) which most unnerved me. The way they moved in the breeze – just as they would have done at the height of Holocaust. It was this ‘everydayness’ which, for a second, enabled me to straddle past and present.

Portals to the past, these trees were once gateways to death. It was amongst these trees that victims were kept before being sent to the gas chambers nearby.

A work I created in 2009 – The Woods, Breathing – took the form of words taken from two books: one the Diary of Adam Czerniakow, the other, Pilgrims of the Wild by Grey Owl, a book which Czerniakow had read in the Warsaw ghetto.

The words were planted amongst the trees of Shotover. Some of them – quite mundane – could almost have been describing the place in which I had placed them. For example, ‘Silver birches’ pictured below.

Others, like ‘Identity Papers’ (below) called to mind the reality of Czerniakow’s world; one not so dissimilar from ours, in terms of the fact it was real.

A quote from his diary illustrates this: “In Otwock. The air, the woods, breathing.” It describes a moment of respite from the horrors of the ghetto and while we might find it hard, despite our greater efforts, to empathise with life in such appalling conditions, we can empathise much more readily with that moment in the woods.

Below is a painting by Paul Nash entitled ‘We are Making a New World.’

The trees in this landscape have been splintered by shellfire. The following extract from Neil Hanson’s book The Unknown Soldier is a vivid description of the landscape Nash is depicting.

Clearly visible on the skyline, High Wood was a long low hill, a natural strong point, the highest ground in this low-lying area. Densely forested when the fighting began, the months of incessant shelling had left it a wood in name only, reduced to a wasteland of of shell-holes, over-running with water, its trees splintered to matchwood, leaving smashed stumps barely two feet above the ground, and shattered rock and churned earth, like a sea all heaving in anger.

Below is a trench map showing various woods in an area of The Somme.

One could say the Great War was the start of the modern age; the past, in the form of dense woods had been obliterated.

The woods have grown back and walking within them, it’s almost impossible to appreciate what they were like for soldiers during the Great War. As in Auschwitz-Birkenau, it was the nowness of my being there, of experiencing the present in, for example, the moving of the trees, that enabled me to establish some kind of connection with those who had lived through such a catastrophic event. With the return of the trees comes the return of the past.

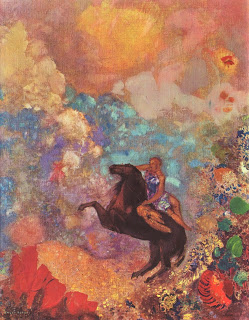

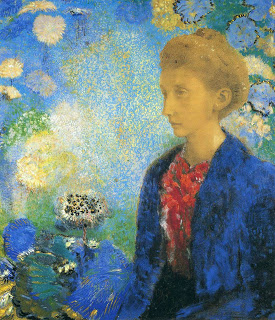

Backdrops (Odilon Redon)

A Backdrop to Eternity

Below is a typical, early 20th century studio portrait. The subject – a boy – sits on a prop. Behind him hangs a backdrop on which is painted an idealised scene – something like the view of a country estate with trees, balcony and lake.

When I first got the photo (as part of a job-lot of old photographs) I gave it a cursory look and that was that. I hardly noticed the backdrop behind, which is perhaps the point.

The image below is another studio portrait from around the same time. The subject rests upon a prop – in this case a chair. Behind him hangs a backdrop – a bucolic scene replete with woodland path, flowers, river and bridge – and again, when I first looked at the photograph – given to me as part of a collection of around 200 – I hardly noticed the backdrop; my eyes were drawn only to the soldier. But as I began analysing the backdrops of other postcards in the collection, becoming more aware of the differences between studio-based portraits, and those taken in more informal, often domestic settings, I started to think more about these backdrops.

“We whose generations are ordained in this setting part of time, are providentially taken off from such imaginations. And being necessitated to eye the remaining particle of futurity, are naturally constituted unto thoughts of the next world, and cannot excusably decline the consideration of that duration, which maketh Pyramids pillars of snow, and all that’s past a moment.”

That click of the camera, that moment, would, when pressed against the face of eternity, encompass all that has so far come and gone since the Universe began. It’s a concept quite impossible for the human mind to hold and so – in some – the void is filled with God and an afterlife. After the war, many of the bereaved tried to fill the void left in their lives through Spiritualism, attempting to contact their loved ones in an eternity filled perhaps with pre-war, picture-postcard landscapes; trees, fields, flowers, rivers and so on. And in many ways, the photographs of the soldiers above, become not images of insignificant moments made before their departure, but images of their place in an eternal moment once the war was done.

After the war, the sense of emptiness must have been everywhere. Every insignificant moment – barely acknowledged before the war – now pregnant with a pervasive sense of incomprehensible loss. The world was outwardly the same, shifted just a little, but it had taken the lives of millions to push it there.

Redshift

Anyone who has stood on the edge of the Lochnagar crater at La Boiselle in France, cannot help but be overawed by its vast size. The result of a huge mine, detonated below ground at 7:28am on 1st July 1916 (the first day of the Battle of the Somme), the crater is almost 300 feet in diameter and 70 feet deep.

“The whole earth heaved and flashed, a tremendous and magnificent column rose up in the sky. There was an ear-splitting roar drowning all the guns, flinging the machine sideways in the repercussing air. The earth column rose higher and higher to almost 4,000 feet. There it hung, or seemed to hang, for a moment in the air, like the silhouette of some great cypress tree, then fell away in a widening cone of dust and debris.” The words of 2nd Lieutenant C.A. Lewis of No. 3 Squadron RFC who witnessed the blast.

Thinking more on this, I had in my mind’s eye an image of the past receding – a past moving away from us here in the present-day. I thought about sound and how, as it moves away, its pitch shifts due to the fact its wavelength stretches (what’s known as the Doppler effect). I thought then about light, how as it moves away, its wavelength stretches and shifts towards the red end of the spectrum. It’s through this redshift that scientists can deduce how far away an object (such as a star) is from the Earth and how fast it is travelling. Redshift is often used as a way of explaining the Big Bang. If you imagine the Big Bang (or indeed any explosion), you can easily visualise how everything emanating from within it would move away from its centre. Everything we see in space today is a result of that first explosion. As a result, everything is moving away – something we can see in the redshift of distant galaxies.

As we move away from the catastrophic events of World War I, and as we approach its centenary, the craters and shell-holes that pockmark the old Western Front, become – like the trenches – filled with earth. They become grown over with grass, flowers and trees; and this gradual retreat towards the natural world is, I think, a kind of redshift in the landscape.

I want to explore this idea and to think more about an audio piece I’ve been working on: a recording of my mum and aunts singing Where Have All The Flowers Gone in 1962.

Helen Thomas

Extract from The Wild Places by Robert Macfarlane.

“She [Helen Thomas] recalled afterwards that Gurney, on being shown the map, took it at once from her, and spread it out on his bed, in his hot little white-tiled room in the asylum, with the sunlight falling in patterns upon the floor. Then the two of them kneeled together by the bed and traced out, with their fingers, walks that they and Edward had taken in the past…

Helen returned to visit Gurney several times after this, and on each occasion she brought the map that had been made soft and creased by her husband’s hands, and she and Gurney knelt at the bed and together walked through their imagined country.”

Landscape Therapy

It isn’t uncommon, when faced with an issue or issues in one’s life, to seek help from a psychotherapist or counsellor. I have recently done just that and found it a rewarding experience. I spoke at length, the therapist listened intently, then aimed a well-honed question. In an instant the angle from which I’d been viewing my problem shifted; there wasn’t an answer as such, but an increased sense of clarity. It was almost like walking lost through a thicket, meeting a guide and being taken to hitherto unknown vantage points from which the landscape could be seen more clearly. By the end of the session, I not only had a better understanding – and appreciation – of the ‘terrain’ through which I’d come, but I could see the path along which I’d walked, with all its twists and many wrong turns.

Traumatic landscapes have always interested me and my work over the last six or seven years has looked at how we – through art – can empathise with those who suffered in such environments, for example in the Holocaust or World War I. These landscapes – and I’m thinking in particular of battlefield sites on the Western Front – have suffered incredible trauma and as we walk through them, the relationship between landscape and walker becomes like that between patient and therapist.

In those moments of clarity I mentioned before, it was as if my therapist and I had for second become one and I have often experienced the same thing when walking, where for a second, I become one with the landscape and vice-versa. A turn of the head, a shift in viewpoint becomes the well honed question, to which the landscape responds with an answer; a depth is revealed, empathy established with some unknown person in the past. Often its fleeting, but one’s understanding of that particular place is enhanced beyond measure.

The landscape knows itself a little better. So does the walker.

“For the things of this world are their stories, identified not by fixed attributes but by their paths of movement in an unfolding field of relations. Each is the focus of ongoing activity. Thus in the storied world… things do not exist, they occur.” Tim Ingold, Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description.

WWI Portraits: Inside, Outside

Below are two portraits, each of a soldier about to leave home to fight in what we now know as the Great War.

In the first picture, taken in a studio, the soldier is pictured in front of a painted backdrop. In this idealised landscape, the leaves of the trees are out, the flowers are always in bloom, and behind an incongruous chair a river flows nowhere beneath a bridge. In the second picture the trees are bare, there are no flowers and a path leads to the rear of what appears to be a garden.

In the first picture, the soldier could almost be an actor standing on a stage. In the second, the soldier is – one assumes – at home, although in a sense, he too is playing a part. His however is a picture of departure; an image pregnant with the weight of all we know was about to befall him and thousands like him. The image of the soldier standing in the studio, tells me only about that time between the shutter’s opening and closing. There is no sense of an entrance or indeed an exit – whereas with the second image, one can imagine the soldier standing in place, then leaving once the picture was taken.

I can empathise with the second soldier much more readily because I know what it’s like to stand in a garden in winter. Somehow, the fact the trees are bare, along with the hedge running the length of the garden helps me make a connection. The branches and twigs are stark, vivid, real. With the first soldier, the backdrop is a fantasy and connecting with him is like trying to connect with someone else’s dream.

The main difference between the image above and those below is that in all those below I can feel the scene I’m looking at. I can almost hear it.

It was, I think, taken as the sun came up in the morning or as it set in the late afternoon…

Looking at it, I’m reminded of a photograph from my own childhood (below), taken in the winter of 1984.

Goethean Observation of a Fosslised Shell

Part 1

The object is a lump of soft grey rock. It is irregular in its appearance except for a small part about 1cm square, which is extremely regular in its form. The piece of rock is heavy and feels quite dense and sits comfortably in the palm of my hand. If I scratch the surface with my finger nail a mark is left behind. The texture of the piece of rock is rough but at the same time its softness makes it feel quite smooth to the touch. Part of its surface is smoother than that on the other side and it is on this side I can see the regular pattern of lines and a couple of other circular imprints. This smooth part of the rock feels softer than that on the outside – indeed there seems to be a distinction between an outside and an inside. The inside is defined in some respects by what looks like a cut. The ridge is about a centimetre deep and is irregular in shape, although it seems, compared with the other side, more regular.

The very distinguishable pattern is a shell. I can see the ridges running from its outer edge at the top to the bottom. There also seems to be a dark patch running from one side to the other about a third of the way down from the top. There is a distinguishable bulge at the bottom of the shell where all the lines meet.

The rock feels cool but not cold (as I write my observations outside in the garden, a breeze is blowing, turning the pages and agitating the protective wrappings in which I keep the rock). Looking carefully at the surface of the rock, on what I have called its outside, I can see small patches of grey which unlike the rather dull complexion of the rock are quite shiny, reflecting the light of the evening. The rock seems encrusted with crumbs of rock which it seems I could easily rub off with my thumb.

The rock has about nine surfaces or faces including the ridge mentioned earlier and the face on which you can find the form of the shell. Whereas the crumbs of rock and the lines, imprints and grey shining patches seem an integral part of the rock; the shell-like form seems (although it is made of the same thing) separate somehow. It is both the rock and something entirely different.

As the wind blows a little, everything moves it seems, save for the rock (and the table on which it is resting). It feels in my hand extremely fragile, as if should I drop it, it would break apart. Certainly I feel as if I could break pieces off with my bare hands.

Although to the eye there are faces of the rock which seem rough and those which seem much smoother, it feels nonetheless as I hold it in my hand the same texture all over. It has in some respects the look of a piece of bone (like a hip joint) or a worked piece of stone – an ancient tool for example.

As I write I can hear the odd shout in the street.

Part 2

The piece of rock is a fossil found in a large piece of rock next to cliffs at Charmouth. The rock is dated to around 195 million years old. The whole of this piece of rock has therefore been part of an inside for a period of time that is unimaginable in my human brain. It was once part of the cliff and therefore one can imagine that it would have been under a great weight. Of course the piece of rock only became a piece of rock because the cliff face eroded. Then part of the face collapsed, a smaller piece was broken open and inside the shell was revealed. For much of its incredible life span then, it wouldn’t have been a piece but rather a whole. And, therefore, this piece wouldn’t have born the whole weight of the cliff upon its shoulders; this weight would have been distributed throughout the layer of which it was a part.

The shell would, like the rest of the rock, have been covered (surrounded by ‘other rocks’). It is the breaking open of it which gives it a sense of being ‘inside’. Imagining it surrounded by rock, a seamless expanse of rock, one does have a sense of darkness and a sense of weight – immense dark and immense weight. When I found it and broke it open, there was, suddenly the sense of lightness and indeed light, whereupon the pattern of the shell’s form was revealed for the first time in over 195 million years.

The light from the sun in the present day allows me to see the lines – the same sun that would have shined above the sea 195 million years ago.

This sense of an outside and an inside: the inside is hidden from view – invisible, and yet it exists. Looking at a cliff one sees colossal weight, density and reaching my eyes inside, I can picture only darkness. And yet, looking at this rock, one sees a form which is fragile, delicate, regular, light. The cliffs must be full of such tiny shapes – full of fragility; a delicate, lightness of touch. This mirrors the time before the rock was formed, when the shell was a living creature in the seas. One can imagine the light of the sun on the sea, the lightness of the creature – its fragility as it lived. There is a sense of the sea being light (in terms of sunlight and a lack of weight) and yet the sea is also impenetrably dark and heavier than the cliffs which we see today.

(The cliffs are little different then to the sea. They are not static, but are moving, slowly – too slow for our eyes until the second they slide.)

The shell would have been compressed on the sea floor over tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, millions of years. Its outline, its shape, its ridges and perhaps its surface pattern were fixed as lines of incredible delicacy. The sea levels fell, the rocks shifted: huge, unimaginable forces, acting over vast, incomprehensible spaces of time – and yet this shape and these lines have remained. And all the while these lines have existed – this tiny shape has existed, whole epochs have come and gone – creatures have evolved ; whole species, including the dinosaurs have come and gone; the great mammals and so on. And finally man has evolved too. There is the sense that I’m looking only at the shell rather than the rock of which it is a part.

This lump of ‘unremarkable’ rock, shapeless, rough, grey, ugly, is just as ancient and incredible as the beautiful, perfect shell which is a small part of it.

Part 3

Movement. Frozen.

The individual object which is not a part but a whole.

Air, light, water, colour condensed to make this soft, grey mass.

Delicacy of life translated into the delicacy of the small pattern on the rock’s surface.

(The light fades outside where I write and the shape of the shell begins to dissolve into the rock).

Movement of the shell. Movement of continents.

Movements of creatures, of time on an evolutionary scale. The weight of time which this patten of lines has withstood for 195 million years.

(What can humans withstand as individuals and as a species?)

(Colours begin to face into darkness).

Part 4

Movement returned to the rock from the moment it was found and carried in my hand – carried into the garden this evening.

Movement of that creature, of everything that sank to the seabed, of the water above, whose weight pressed upon it – now becomes/joins with my own movement through time/this world.

The light that allows me to see the lines of the shell – its shape, eyes which would have evolved since that shell was in the sea.

The delicacy of light, of eyes.

Lightness. Weight. Pressure.

Light. Vision.

Lines.

Two Shells

I found the shell on the left on a beach in Spain last week. The shell on the right (on which I’ve previously written), I found in 195 million year old rock on a beach in Charmouth at New Year.

Shadows 3

I was looking at something recently which made me think of the work I’ve been exploring around the backdrops used in World War One postcards, such as that below:

Beneath the floor

I’ve always found it amazing, when, on a programme like Time Team, an apparently empty field is shown to have once been the site of some vast Roman villa; how something so grand and seemingly permanent can one day be lost to both memory and the landscape; a memento mori of inscribed lines on quite an epic scale. The recent discovery of the tomb of Richard III is perhaps the most vivid illustration of this; how the grave of so eminent a man could be buried (albeit hastily) in the choir of a friary, only for all trace (of both the grave and the friary) to be lost beneath the tarmac of a nondescript car park. In Urne Burial (1658), Sir Thomas Browne wrote:

“There is no antidote against the Opium of time, which temporally considereth all things; Our Fathers finde their graves in our short memories, and sadly tell us how we may be buried in our Survivors. Grave-stones tell truth scarce fourty years; Generations passe while some trees stand, and old Families last not three Oaks.” In the garden of the house in which I grew up, there was an oak tree – now lost; a victim of the relentless drive to build flats and houses on every scrap of space ‘available’.

In the shade of that tree (visible above on the right hand side) and the lawn beyond its reach, I spent many childhood days, playing football, high-jumping (badly), playing at being ‘The Professionals’ and, on one occasion, holding a sale to raise money for charity. But in the last year, a few years since my dad sold up and left, half the house has been pulled down (including most of my bedroom) and a new one built alongside, covering most of the garden.

The lawn on which we had picnics, over which the rabbit – Patch – thundered, chasing Sammy the cat – and the beds beneath which those same animals, amongst many others, were interred, is now itself buried beneath new concrete floors and builder’s rubble.

It’s strange to think of someone standing in a kitchen, or sitting in a living room, on the exact same space where we once played.

And that’s what made me think of those Roman villas lost to the past beneath the ground; all those memories attached to those buildings which have soaked away like water, into the ground over the course of two millennia.

The garage is now a particularly mournful sight. Here, I spent many hours (often with enormous hair as evidenced by the photograph) on the drive, playing football with my brother and friends – or sometimes by myself (I can still hear the sound of the plastic ball skitting across the concrete and the bash of the blue metal door which was sometimes the goal). The sounds too at night of my dad arriving home in the car, the radio blaring as the wooden gates were opened; the whoosh of the garage door being lifted, are memories more permanent than the concrete drive itself. Now the garage is a sorry looking creature, whose full demise is certain, along with the shed tucked away behind (in which we sometimes slept on warm summer nights).

The photo below of me and my cousins (on my dad’s side) was taken when I was a baby in the summer of 1971.

The patch of grass on which we’re sitting would soon become the garage….

Lines Drawn in Water

The following passage is taken from ‘The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot’ by Robert Macfarlane. In a chapter on water he writes:

“The second thing to know about sea roads is that they are not arbitrary. There are optimal routes to sail across open sea, as there are optimal routes to walk across open land. Sea roads are determined by the shape of the coastline (they bend out to avoid headlands, they dip towards significant ports, archipelagos and skerry guards) as well as by marine phenomena. Surface currents, tidal streams and prevailing winds all offer limits and opportunities for sea travel between certain places…”

This reminded me of some work I did on my ancestor Stephen Hedges who was transported to Australia in 1828. In particular I thought about the route The Marquis of Hastings (the ship on which he sailed) took from Portsmouth to Port Jackson (Sydney) which I mapped using Google Earth and coordinates written down in a logbook by the ship’s surgeon, William Rae.

Macfarlane also writes:

“Such methods would have allowed early navigators to keep close to a desired track, and would have contributed over time to a shared memory map of the coastline and the best sea routes, kept and passed on as story and drawing…

Such knowledge became codified over time in the form of rudimentary charts and peripli, and then as route books in which sea paths were recorded as narratives and poems…

To Ian, traditional stories, like traditional songs, are closely kindred to the traditional seaways, in that they are highly contingent and yet broadly repeatable. ‘A song is different every time it’s sung,’ he told me, ‘and variations of wind, tide, vessel and crew mean that no voyage along a sea route will ever be the same.’ Each sea route, planned in the mind, exists first as anticipation, then as dissolving wake and then finally as logbook data. Each is ‘affected by isobars, / the stationing of satellites, recorded ephemera / hands on helms’. I liked that idea; it reminded me both of the Aboriginal Songlines, and of [Edward] Thomas’s vision of path as story, with each new walker adding a new note or plot-line to the way.”

One of the things I like about William Rae’s logbook of the journey aboard the Marquis of Hastings is the description of the weather. The world aboard a prison ship in 1828 is far removed from our experience, but we know weather and can therefore use his descriptions to bridge the gap between now and then; moving from – to use Macfarlane’s words – “logbook data” through “dissolving wake” and “anticipation,” all the way back to “planned in the mind.” The description of the weather therefore becomes a poem of sorts, echoing what Macfarlane writes above; how sea paths become narratives and poems, allowing me to step back into the mind of my ancestor.

Fresh Breeze. Mist and rain.

Strong Breeze. Cirro stratus. Horizon hazy.

Hard gale & raining. Heavy Sea.

Hard rain & Violent Squalls. Hail & rain.

Glimmerings: The War Poets, Paths and Folds

One of the nicest compliments I received during Friday’s private view was ‘…these remind me of Siegfried Sassoon…’. The works in question were those images of imagined World War I landscapes painted onto folded paper, one of which I have shown below:

In fact, the war poets were brought up a number of times in relation to these works which – for obvious reasons – pleased me enormously. But, I wondered what it was about these pieces which called to mind the poets?

One of the poets I’ve become increasingly interested in, is Edward Thomas – killed at the battle of Arras in 1917. I first became aware of his work whilst reading a book of World War I poetry, in which I found his poem ‘Roads’ (a poem I’ve already discussed in relation to my work). It was then in Robert Macfarlane’s book ‘Wild Places’ that I encountered Thomas again, this time in relation to another poet, Ivor Gurney. In a previous blog I wrote:

After returning from the war, Ivor Gurney, like so many others suffered a breakdown (he’d suffered his first in 1913) and a passage in Macfarlane’s book, which describes the visits to Gurney – within the Dartford asylum – by Helen Thomas, the widow of Edward Thomas is particularly moving. Helen took with her one of her husband’s Ordnance survey maps of Gloucestershire:

‘She recalled afterwards that Gurney, on being shown the map, took it at once from her, and spread it out on his bed, in his hot little white-tiled room in the asylum, with the sunlight falling in patterns upon the floor. Then the two of them kneeled together by the bed and traced out, with their fingers, walks that they and Edward had taken in the past.’

Macfarlane discusses Thomas in another book, ‘The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot,’ in which he writes how for Thomas, paths “connected real places but… also led outwards to metaphysics, backwards to history and inwards to the self. These traverses – between the conceptual, the spectral and the personal – occur often without signage in his writing, and are among its most characteristic events. He imagined himself in topographical terms. Corners, junctions, stiles, fingerposts, forks, crossroads, trivia, beckoning over-the-hill paths, tracks that led to danger, death or bliss: he internalized the features of path-filled landscapes such that they gave form to his melancholy and his hopes. Walking was a means of personal myth-making, but it also shaped his everyday longings: he not only thought on paths and of them, but also with them.”

Ever since I walked a path in Wales on which I knew my great-great grandfather walked every day to the mine in which he worked, I’ve been interested in the idea of people as place (and vice-versa) – see Landscape DNA – the simultaneity of stories so far. The path from the small town of Hafodyrynys to Llanhilleth where he worked, not only connected those two places, it also connected me with my ancestor. It did just what Thomas suggested; connected real places but also went backwards to the past and inwards to my own self. As Macfarlane puts it: “paths run through people as surely as they run through places.”

It was important for me that the images shown above did not appear so much as pictures – objects stuck on a wall – as objects of use. I wanted them to appear as if they’d been unfolded rather than simply painted, that like maps, they could be read rather than simply looked at. I wanted them to retain the potential for being folded (which, if they were framed, wouldn’t have been possible) for this inherent potential of folding and unfolding refers back to an observation I made whilst studying an old trench map.

During that observation I wrote, “…the past movements associated with this map are therefore recorded in its folds. It resists being folded any other way.”

The folds in the map are like ancient paths in a landscape. We can walk (within reason) wherever we like through a place, but more often than not, we will follow the way of countless others before us. Paths are themselves like folds within the landscape, and we, like the map, resist being folded any other way.

Macfarlane again writes how for Thomas “…map-reading approached mysticism: he described it as an ‘old power’, of which only a few people had the ‘glimmerings’.”

These glimmerings reminded me of a passage I read in Merlin Coverley’s book Psychogeography, in which he writes: “Certain shifting angles, certain receding perspectives, allow us to glimpse original conceptions of space, but this vision remains fragmentary…”

These ‘glimmerings’or ‘shifting angles’ are best seen or accessed through the everyday; observations of which I record in other map works.

This is something which Macfarlane again seems to allude to in ‘The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot’, when he writes: “The journeys told here take their bearings from the distant past, but also from the debris and phenomena of the present, for this is often a double insistence of old landscapes: that they be read in the then but felt in the now. The waymarkers of my walks were not only dolmens, tumuli and long barrows, but also last year’s ash-leaf frails (brittle in the hand), last night’s fox scat (rank in the nose), this minute’s bird call (sharp in the ear), the pylon’s lyric crackle and the crop-sprayer’s hiss.”

As I have recorded in my text-maps:

A man talks holding his hat

A flag flies, fluttering in the growing wind

The next bus is due

A car beeps

Amber, red, the signal beeps

The brakes hiss on a bus

Maps are objects which we fold and unfold. We unfold them to find our place within the landscape. We fold them and carry them with us. The process or unfolding and (en)folding: the idea that the past can be seen as being enfolded within the smallest objects and everyday observations in vital to my work; as is the way in which we are enfolded (written) into the landscape as we walk; the way in which the landscape is unfolded as we travel across it. Knowledge, likewise, is also unfolded in this way. As Tim Ingold writes in ‘Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description’:

“…knowledge is perpetually ‘under construction… the things of this world are their stories, identified not by fixed attributes but by their paths of movement in an unfolding [my italics] field of relations. Each is the focus of ongoing activity. Thus in the storied world… things do not exist, they occur. Where things meet, occurrences intertwine, as each becomes bound up in the other’s story. Every such binding is a place or topic. It is in this binding that knowledge is generated.”

Empathy is another important aspect of my work and I’ve stated before that empathy is an augmented discourse between bodily experience and knowledge. I like to think that with these works I’ve discovered a means of expressing that.

Finally, the works I’ve made are fragile pieces, and in another passage on Thomas, I found in Macfarlane’s prose a sentence which describes why they should be so: “His poems are thronged with ghosts, dark doubles, and deep forests in which paths peter out; his landscapes are often brittle surfaces, prone to sudden collapse.”

Perhaps this, in part, answers my question above.

Kaleidoscope – Exhibition

Some photos from Kaleidoscope; the exhibition I, along with my fiancee Addy Gardner, are currently staging at The North Wall Gallery, South Parade, Summertown, Oxford. The exhibition runs until 3rd November. See website for more details.

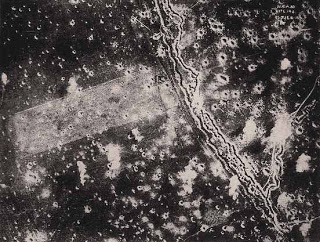

Aerial Views

I worked on a piece yesterday, the origins of which were a GPS trace of trench systems around the village of Serre. I had the idea of ‘colouring’ each segment using ash, graphite and coal dust, but of course the boundaries between these segments blurred into more or less one. However, I liked the look of what I’d produced, which reminded me – in particular where I’d made the lines visible using a palette knife – of aerial photographs I’d seen of the trenches.

The first image I produced:

An aerial view of battlefields taken during the First World War:

Kaleidoscope – coming soon

Read more at the exhibition website.

Weft and Warp

In Tim Ingold’s Being Alive, Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description, he writes the following:

“Recall Hägerstrand’s idea that everything there is, launched in the current of time, has a trajectory of becoming. The entwining of these ever-extending trajectories comprises the texture of the world.”

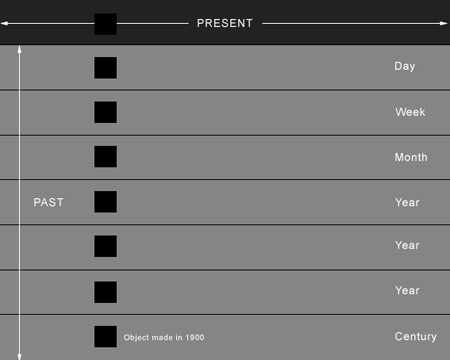

This reminded me of something I wrote some time ago about history and the relationship between history and objects:

“…what we have is not a series of horizontal strata representing stacked moments in time (days, months, years, centuries etc.), but concurrent vertical lines, or what I have called ‘durations’ where each duration is an object, building or landscape feature and where the present is our simultaneous perception of those that are extant (of course, in the case of buildings, individual objects can also contain many separate durations).

It was Bill Viola who said that ‘we have been living this same moment ever since we were conceived. It is memory, and to some extent sleep, that gives the impression of a life of discrete parts, periods or sections, of certain times or highlights’. Similarly we can say that every object, building or landscape feature has existed in one continuous moment and that it is to some extent the passing generations which gives the impression of the past as being a series of ‘discrete parts, periods or sections…”

This is very similar to what Hägerstrand – via Ingold – describes above and in many ways, the second diagram (above), illustrating the idea of vertical durations, is like a loom, where the durations are the warp threads and our perception of simultaneous durations are the weft, leading to an entwining of what Hägerstrand calls ever-extended trajectories making up the texture of the world.

In this analogy we are both the weft and the warp; both a duration and the perceiver of durations. We find something similar to this, again in Ingold’s writing:

“…since the living body is primordially and irrevocably stitched into the fabric of the world, our perception of the world is no more, and no less, than the world’s perception of itself – in and through us. This is just another way of saying that the inhabited world is sentient.”

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- …

- 31

- Next Page »