Part 1

Freshly dug earth, a small pile. A new name on a label planted in it. Twigs and pine cones scattered upon the grass. The wind blows through the trees. Something creaks. The traffic drones in the distance. Grave stones with their backs towards me. Slate-grey surfaces. Voices in the distance talking. Different shades of grey, marked with stains of age. An alarm sounds for a while then is quiet again. The birds chirping around me. The sun catches the top of a smooth marble gravestone. To my right beyond the neatly clipped hedges a burial is taking place – a wicker coffin, the same I saw in a hearse driving past as I walked here. An aeroplane flies overhead and marks its presence with its noise. A fly buzzes. To my right the gravestones show their names. Gold and black lettering in latin and hebrew alphabets. The coffin is lowered into the ground. A man walks past outside and a siren rips through the comparative calm.

Daffodils are growing. The mourners leave the graveside and hug each other.

In the ground, in the grass the plots of land are marked in different ways. Some are slabs of grey, flecked with stain of age and lichen. Green glass beads and bits of gravel, purple flowers or shallow depressions in the ground. Or of course the small mound of freshly dug earth. The mourners are shaking hands. Two men walk between the graves before me, looking for something. One of them yawns with his hands in his pocket. Looking at the back of the gravestones it is as if the graves have turned their backs to me. To find them I will have to walk between them.

The shapes and the heights of the graves are all quite different.

There’s a feather on the ground. Grey and white like the graves themselves.

On the slabs of marble, stone etc. which mark the graves, a pot of broken plant. Holes for putting flowers in. Stones left in memory. Two on one grave. Five on another. Some have none. Others have many more.

Names begin to talk. Dates. Occupations. Places of birth and death. Daisies and last years’ autumn leaves upon the ground. Flowers on one grave; a pot of lavender and white roses amongst them.

Flowers left on turned earth. A mug.

Physician.

Hamburg.

Deported to Riga. December 1941.

Cellist. Artist.

Social Anthropologist.

Geographer.

Moss grows on the glass beads of a grave.

The edges have fallen.

Names. Places and dates slowly melting into the bluish stone. The grass creeps over the edges.

Calgary.

Tartakov. Poland.

Holocaust Survivor.

Reflections of the trees in the polished marble slabs of the graves.

Teacher.

She graced the world.

Lavender growing marks another grave.

Orange lichen creeps up the base of a gravestone.

The stone slab of a grave has almost been swallowed by the grass.

Car doors close as mourners leave the cemetery.

A rose bush, cut back, climbs through a hole.

To so good a man no evil thing can happen.

Wloclawek, Poland.

Nikolai.

Prague.

Perished in Dachau.

Tachow, Poland.

And her family who died in the second world war.

Komotau.

Goerhau.

A small head stone barely poking above the ground.

His work lives.

Komotau, Czechoslovakia.

Who were put to Death in Poland in 1942.

Members of her family massacred in Poland 1942.

Victims of the Holocaust.

He made a new life in England.

A single stone on a grave.

Hamburg.

Komitau (formerly Bohemia)

Minsk.

Riga.

Uneven surface.

Painted stone on a grave.

An artists life.

Scratches on a grave.

Berlin.

My shadow upon the grass before me and as I stand and walk.

Como, Italy.

Swansea.

Cold wind begins to blow. Constant sound of traffic.

Faint names slowly disappearing into a grave.

Vienna.

Breslau.

Berlin. Vienna.

Pomorzany (Poland).

Skoczow (Poland).

Bratislava. Arch. and Eng.

Dried leaves crunch beneath my feet.

The ivy rattles on the tree trunk.

A train horn blows.

Graz (Austria).

Enkirch-Mosel.

Berlin.

A plant pot in its plastic.

A grave grown over with ivy etc.

A coloured windmill turns.

St. Petersburg.

Walking and looking back, the names become once again the plain surfaces of the stones.

A digger fills in a hole in the ground.

The diggers work is done.

Names all face the same way. Dates blur.

For many, the dates are carried everywhere by those who remember them.

Part 2

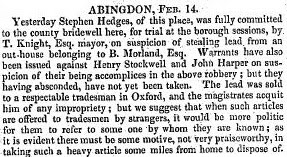

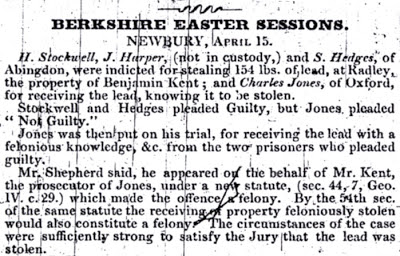

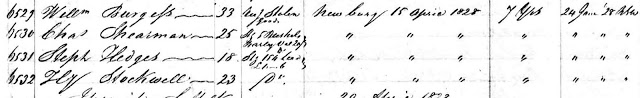

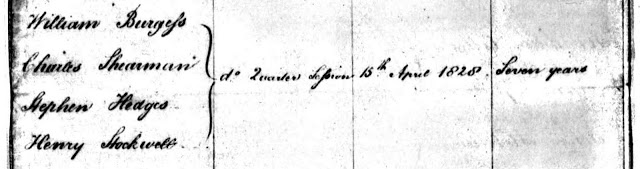

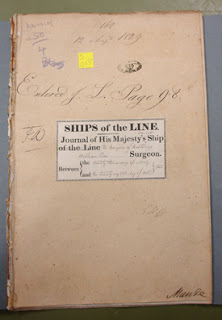

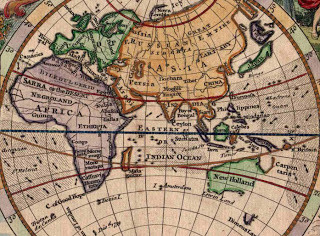

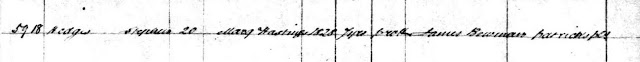

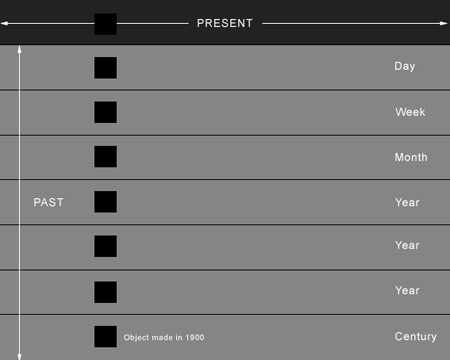

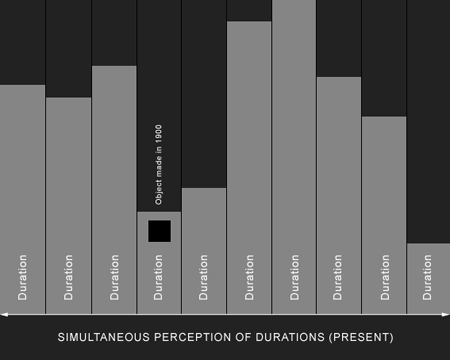

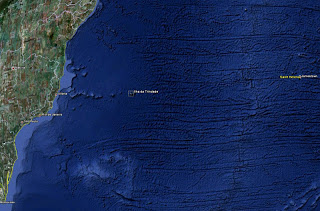

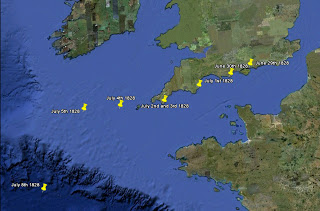

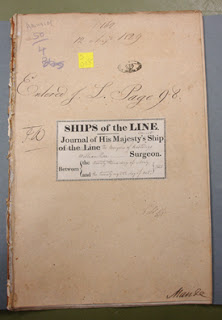

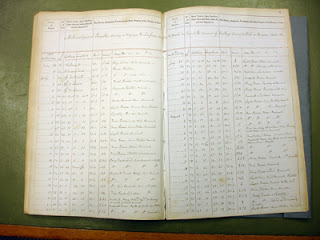

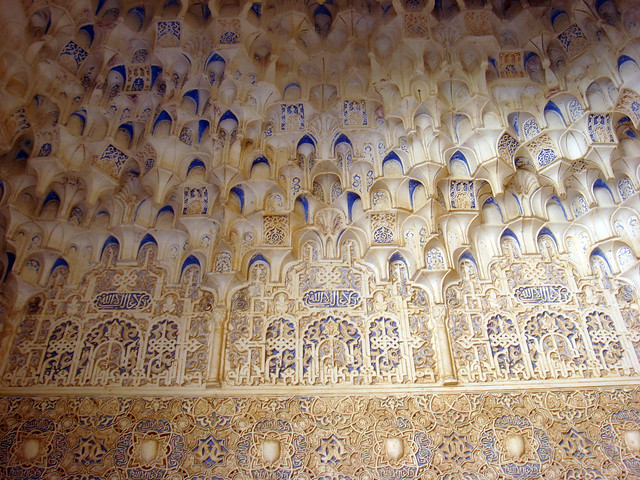

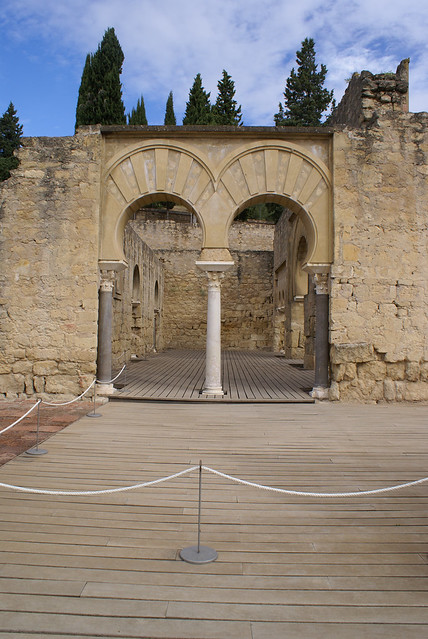

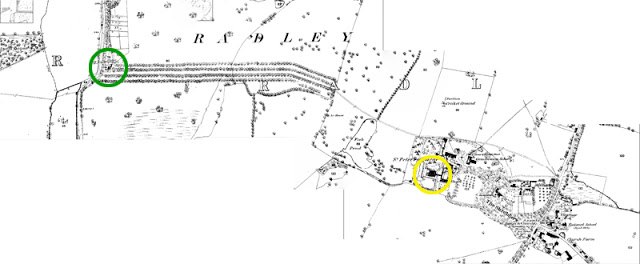

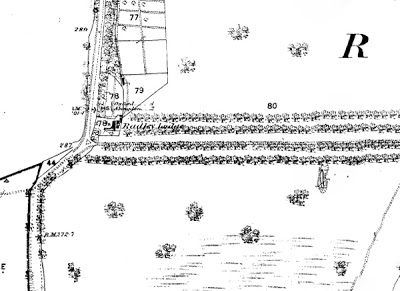

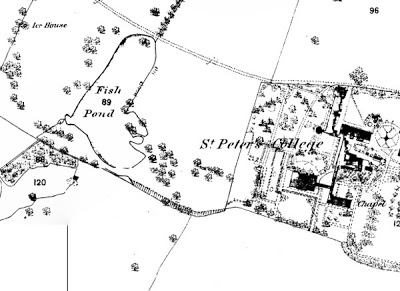

The following is a transcription of stream-of-consciousness thoughts spoken about the cemetery, considering the cemetery in both the past and the future as well as in the present. The images were made during the process as aids to thinking.

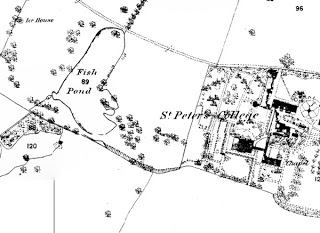

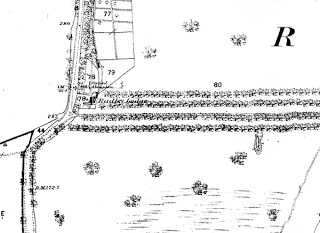

Looking at the cemetery today, not necessarily those graves in the Jewish section but the stones of those buried 50, 60 years or more, one sees how the names slowly recede back into the stone, how the edges of the letters are smoothed, covered over with lichen. How the front of the gravestones become no different to the back. The boundaries of the grave if they are marked with stone begin to collapse. The graves themselves begin to sink. One day the stones will fall and the grass will cover them over and perhaps all that will be left in years and years to come will be a shallow depression in the ground, something like a footprint at the end of one life’s journey.

Cemeteries are places where names go to die. When these names are lost from the stones, when the people that remember them are themselves gone, so we are lost to memory. All that is left to remember us is the ground itself, the world itself. We are that footprint on the ground and beneath the ground our remains live on. They decay, break down and every part of us carries on somehow. Looking at the trees in the cemetery one can see them as metaphors for those buried within. We are in a strange way like seeds in reverse – like an acorn. We begin at the top of the tree before the tree has even grown and we travel between villages and towns, in and around our home towns; every thought we have every connection we make grows its branches, the branches of the canopy until those branches become less and less, albeit thicker and thicker until we’re left with just the trunk marking a small spot in the round and beneath the ground the roots echoing the canopy itself. Perhaps in a way when our bodies decay when we’re broken down into atoms, that is what the roots somehow represent.

And when that tree grows its leaves, every year bears its fruit, we can imagine every place that person had been to, still bearing a trace – a living trace – of their existence. Looking around the cemetery, the Jewish part of the cemetery, one is struck by the places from which people have come, the journeys they have led often in tragic circumstances, which have led them to this small patch of ground.

As I was coming home on the train yesterday watching the landscape pass me by anonymously, one part blurring into the next as if rushing into the past, I saw a small pool of water surrounded by trees into which I threw my eyes imagining what it was like beneath the water’s surface, and there they remained for some of the journey. Whilst I saw the world whizzing by, my eyes were still. All sounds were gone as my thoughts and my eyes drifted beneath the water. And a day later I can still imagine them there the world seems not to have changed and yet a lot of things have happened since then.

One can almost imagine the bodies buried within the cemetery as being like that and the lives they led as being like the man on the train, that though they are still now, in the quiet and the dark, somehow the lives they led are still moving; between Berlin and the cemetery, Vienna and the cemetery, Poland, the Czech Republic, Russia, all the places from which they’ve come.

One can go back before the cemetery was even there when it was just another field, another plot of ground, perhaps it was farmed? I don’t know. Things grew in it of course, the grass grew, trees grew, every blade of grass was more a part of the world than any of these people. And yet within the ground now a wealth of experience has been poured into each of these little holes, experience that is full of happiness, tragedy. Thinking about the trees the branches separating off one should really think of them as one continuous branch that starts high above the ground and snakes its way downwards, every encounter is a knot making up the vast canopy of the tree until it reaches the soil.

When one’s in the cemetery one can’t help think of one’s own death and where we will end up, which patch of ground we will occupy and looking at any patch now one can think whether it will be the place where a life not yet even begun will be remembered by the earth long after the name has died. And in any patch of ground one can also think whether someone is there beneath, unknown, unseen of course, unknowable, but a person who’s left a mark somewhere in the world.

I can’t help but think of the battlefields of Verdun, where from the barren wastes whole forests have now grown, each tree in some way reminding us of the people that died, each branch part of the journey they made through their lives. There’s also the trees grown around sites of the Holocaust those planted to hide the places, those which have grown afterwards. Somehow they too serve to remind us of those lost on those small patches of ground.

There is a connection between this idea of small patches into which so much is poured so many thoughts, so many memories, love, anger, tragedy, laughter. One thinks of a town from which these people were from. Towns in Poland, Germany, the Czech Republic, Russia. One thinks of Vienna and it’s almost as if within that small grave, in that small hole in the ground the whole of that city has been poured. For every city, every place is defined by the people who lived there. So in many respects these are graves not only for people but for places.