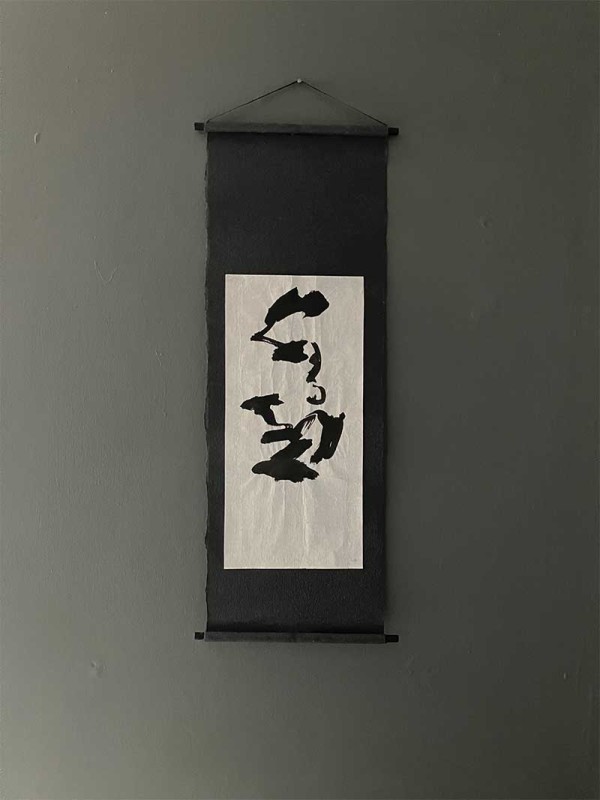

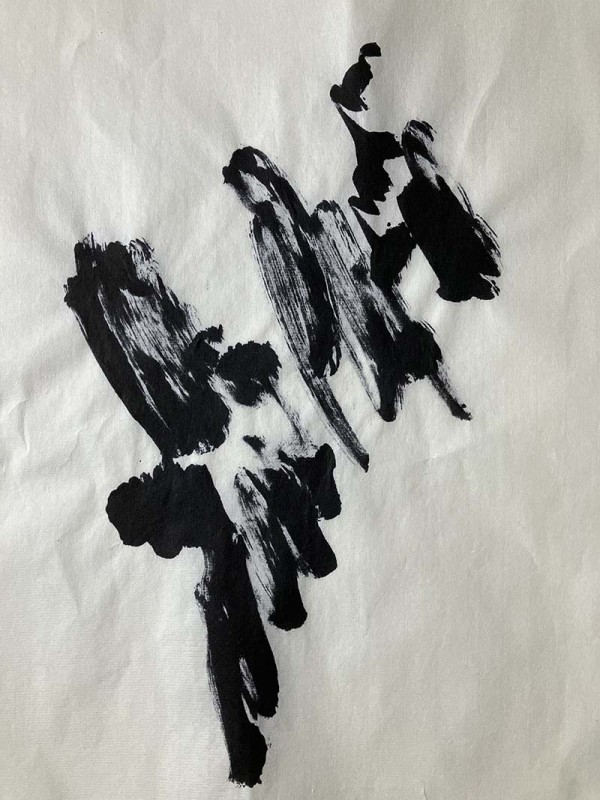

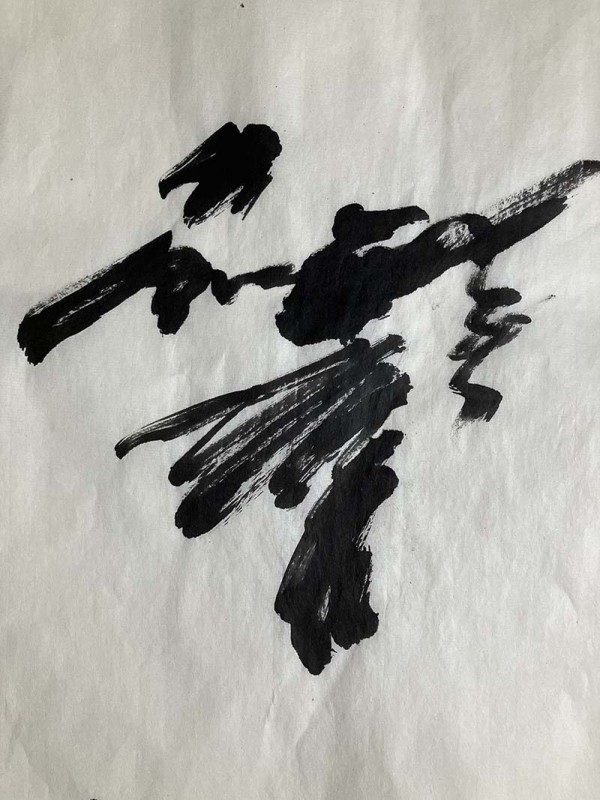

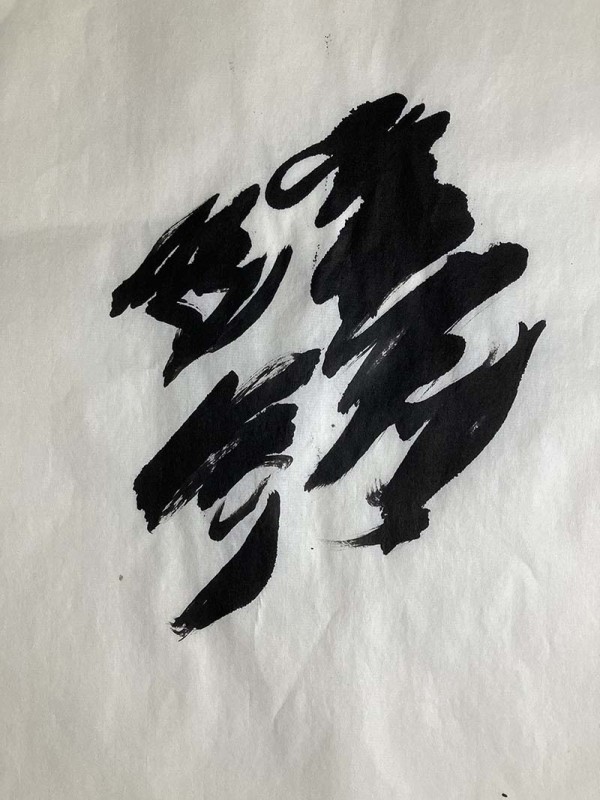

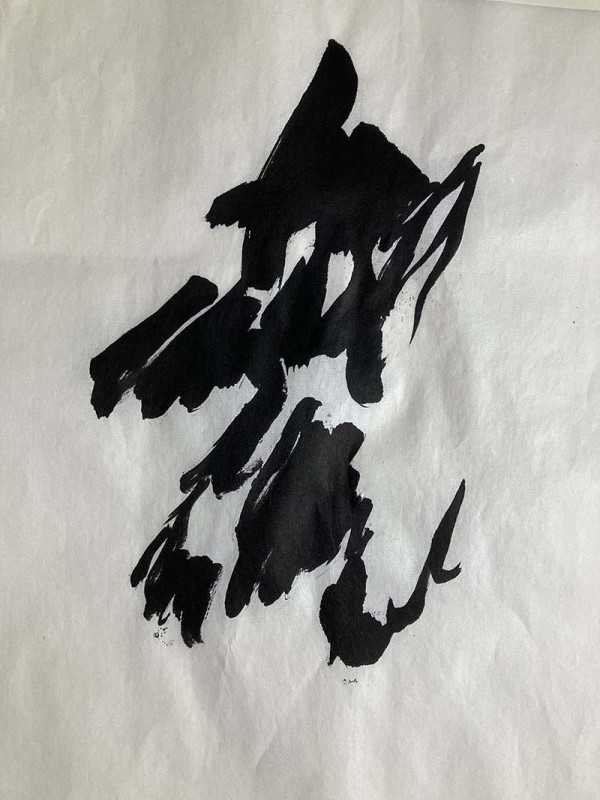

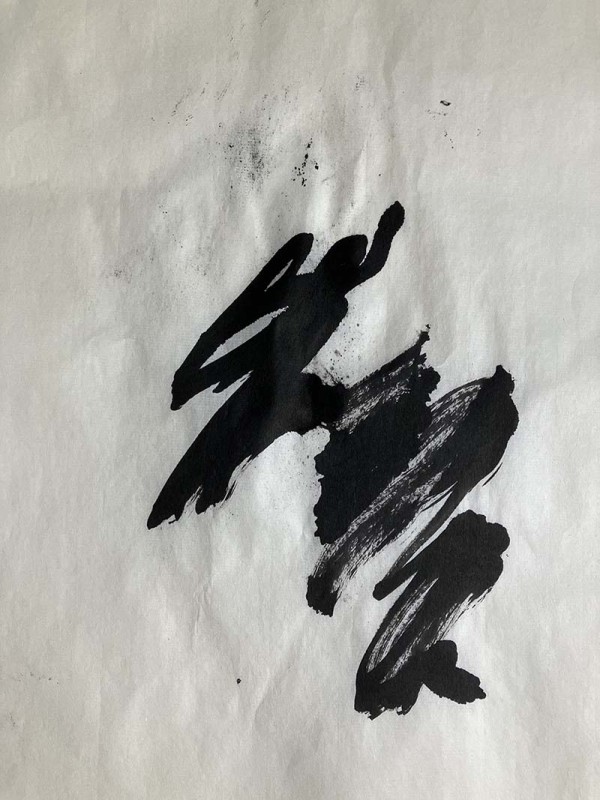

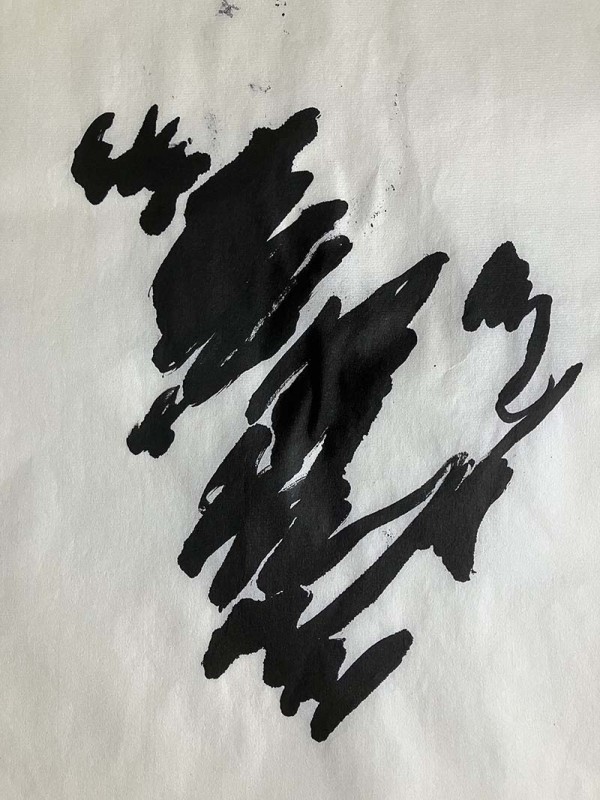

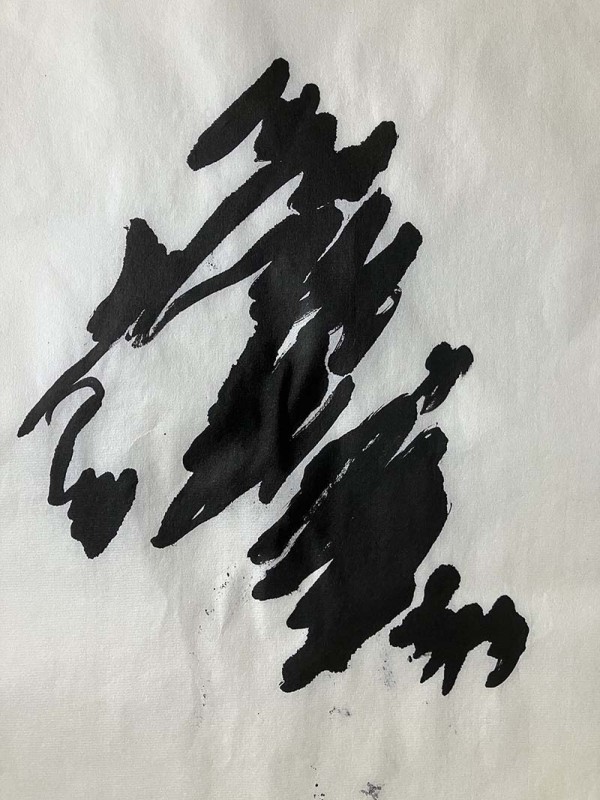

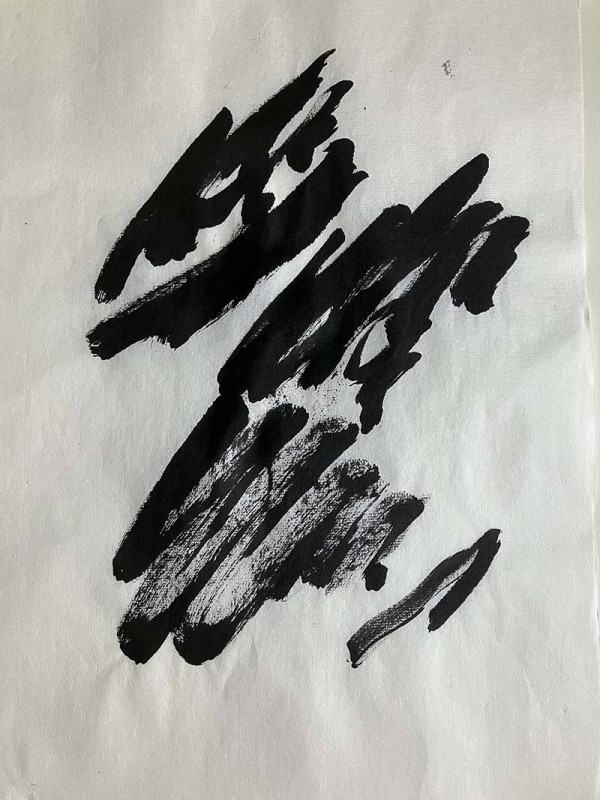

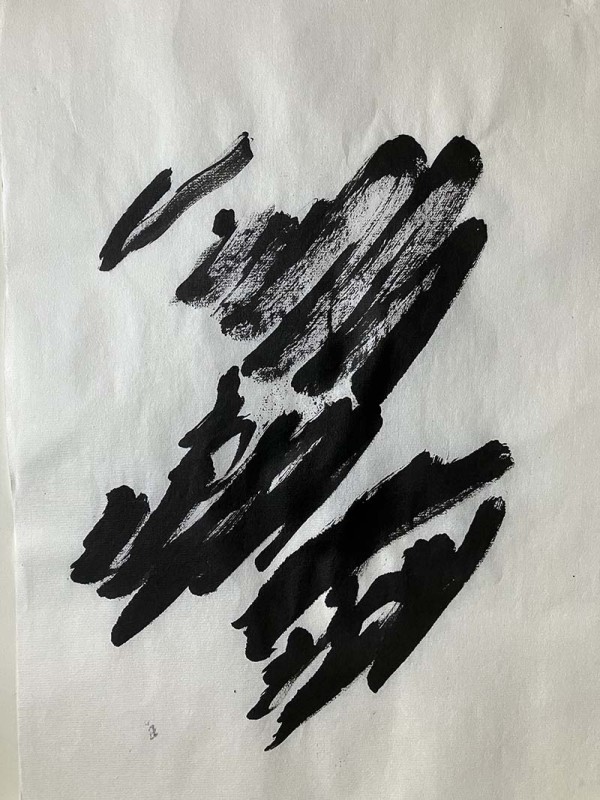

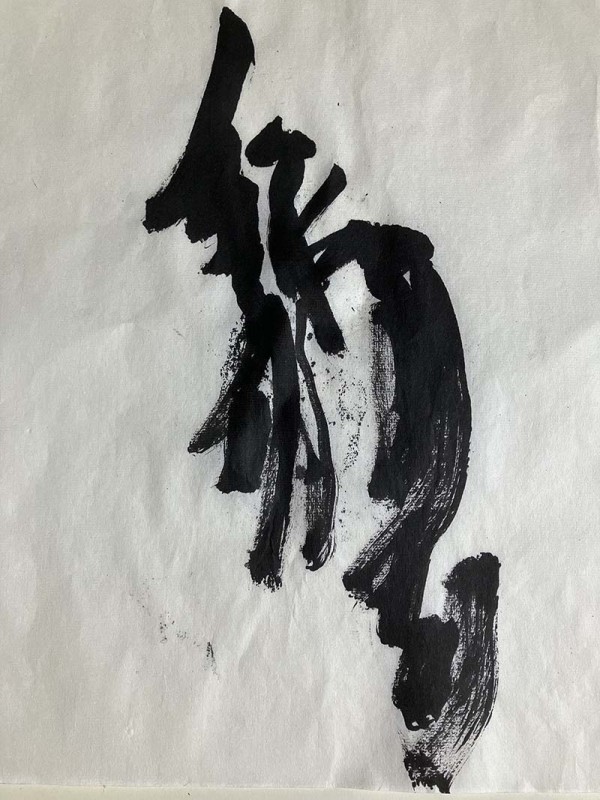

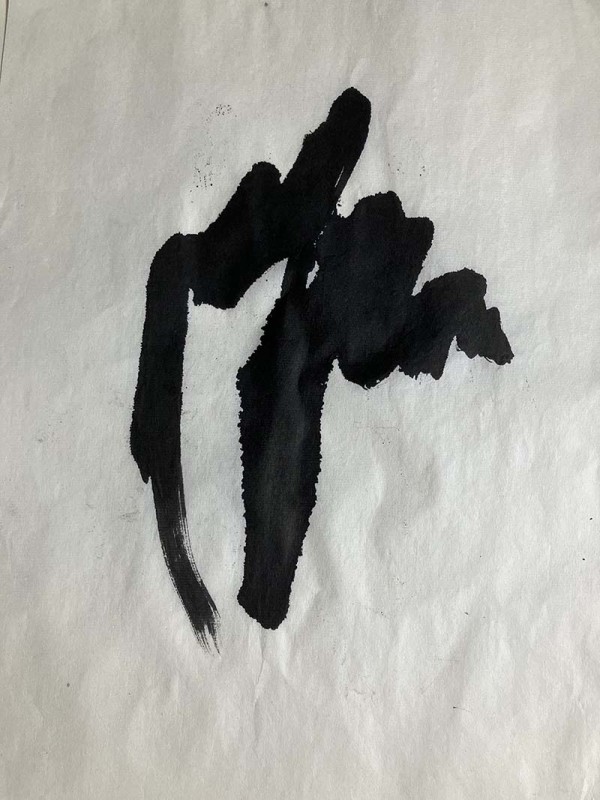

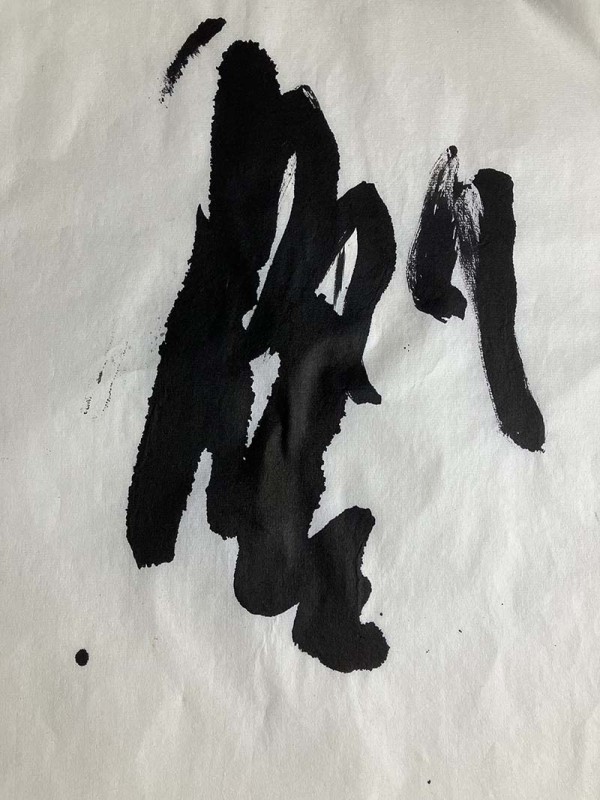

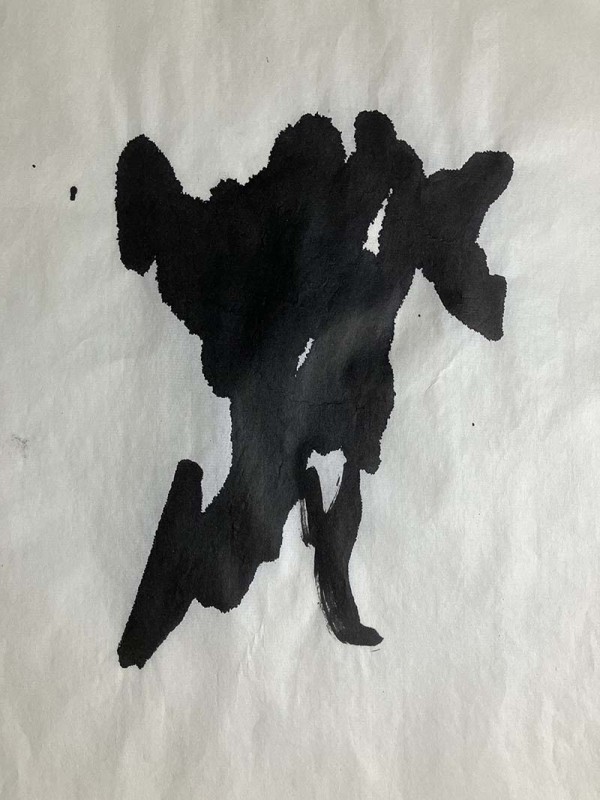

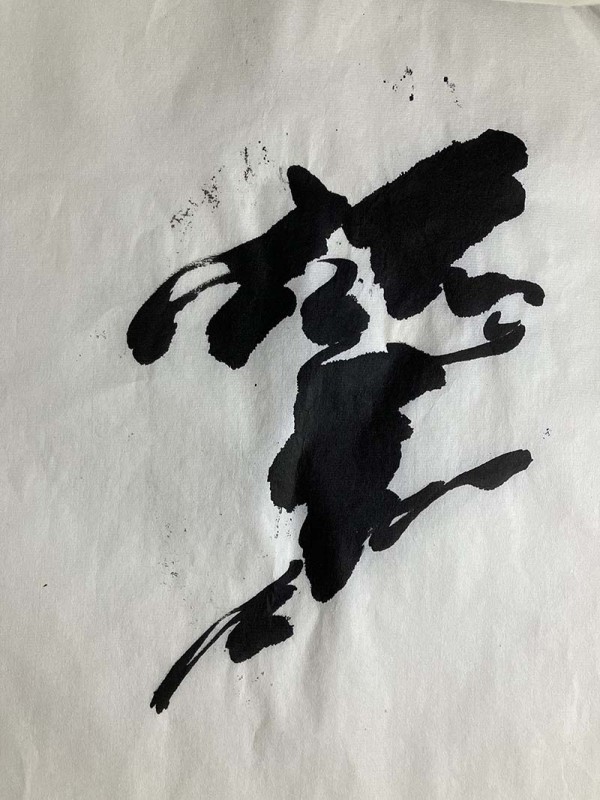

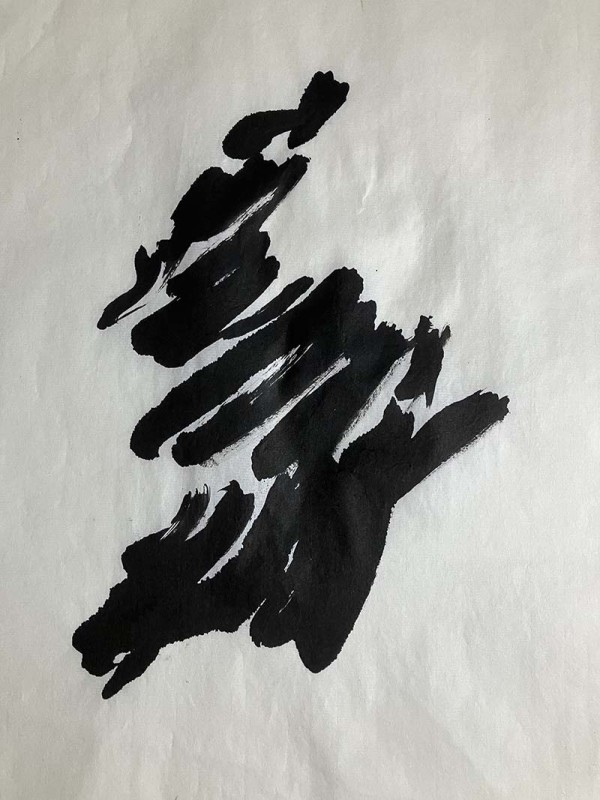

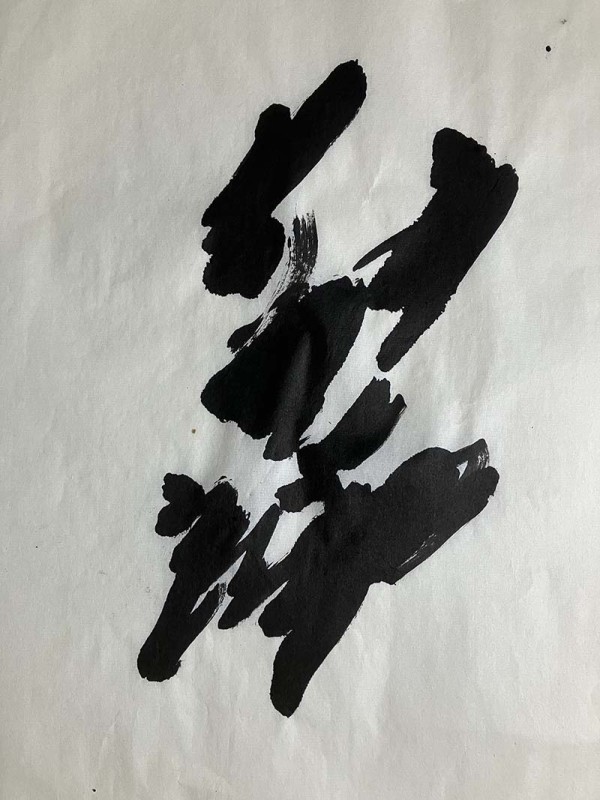

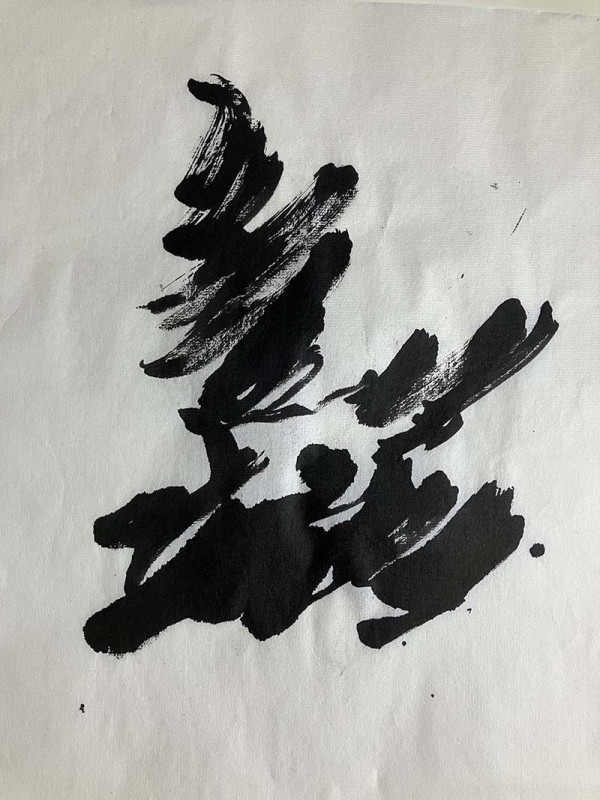

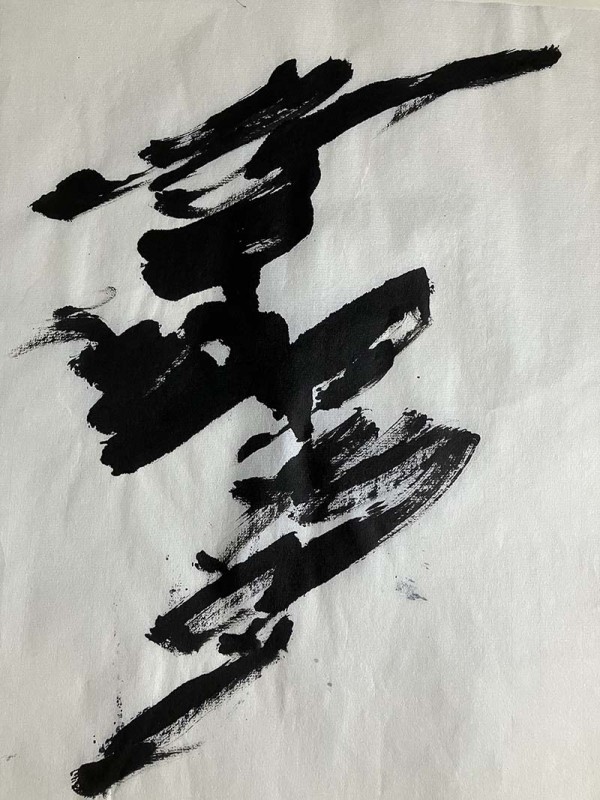

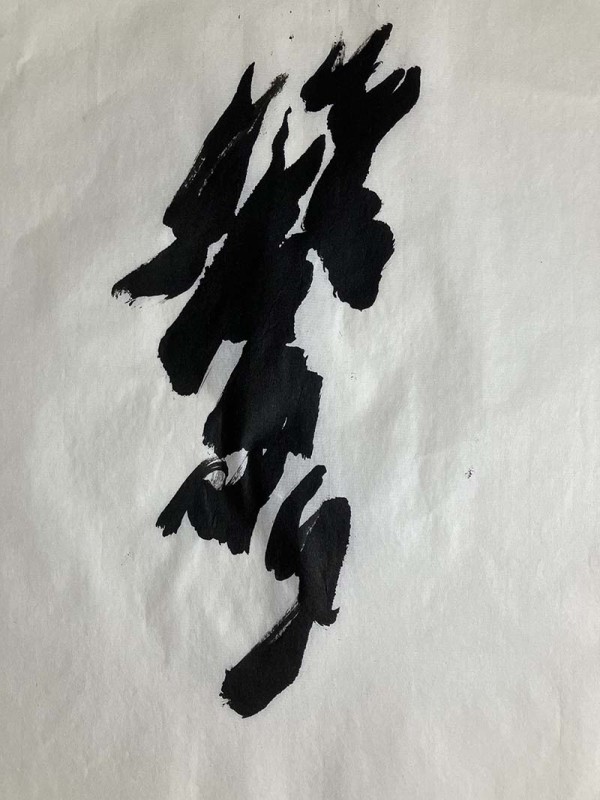

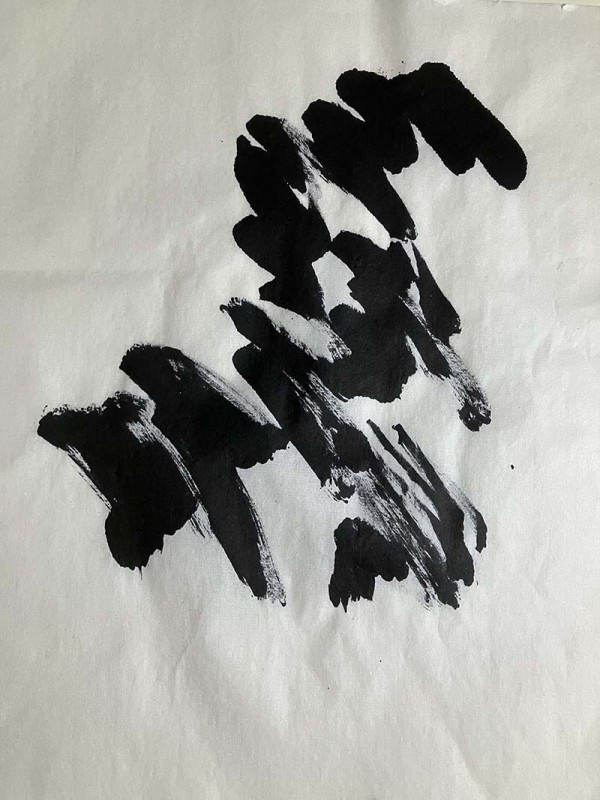

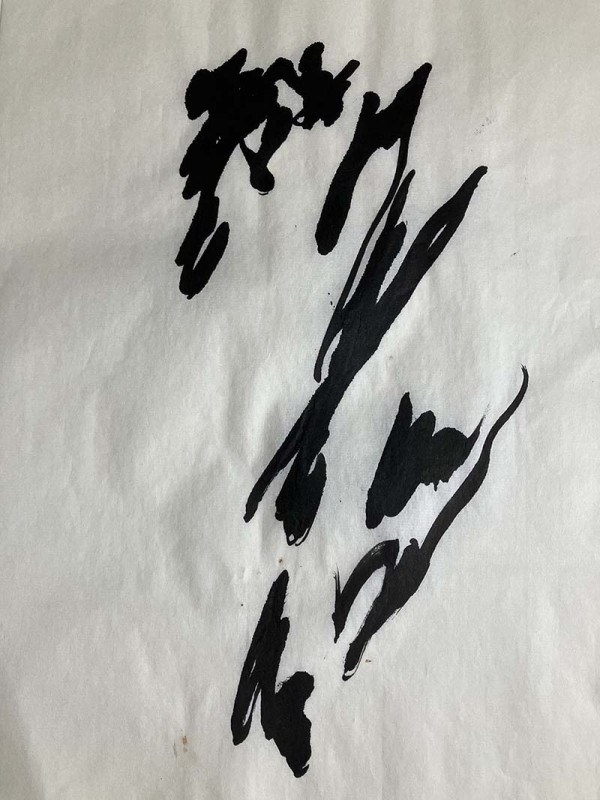

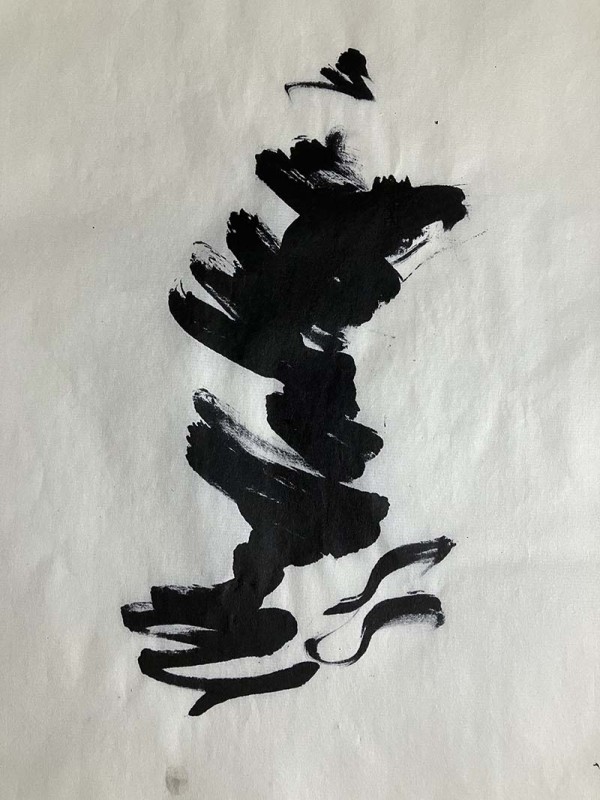

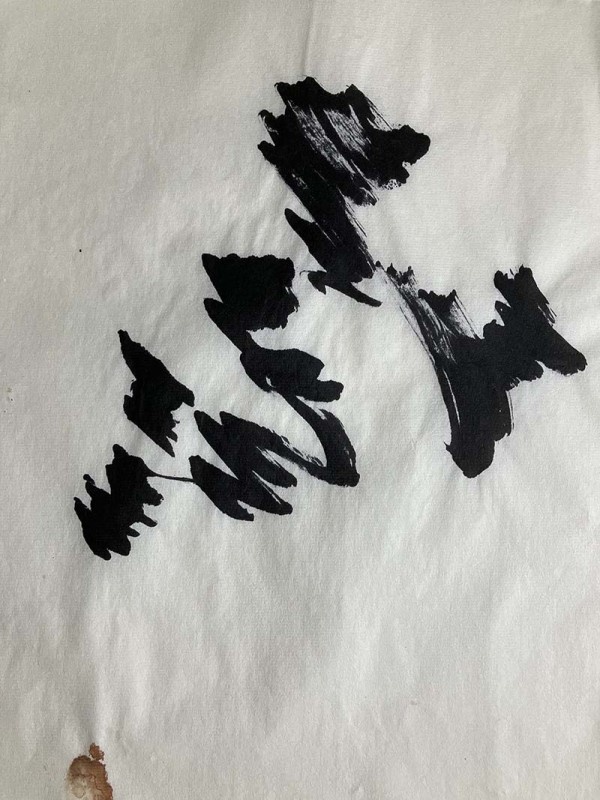

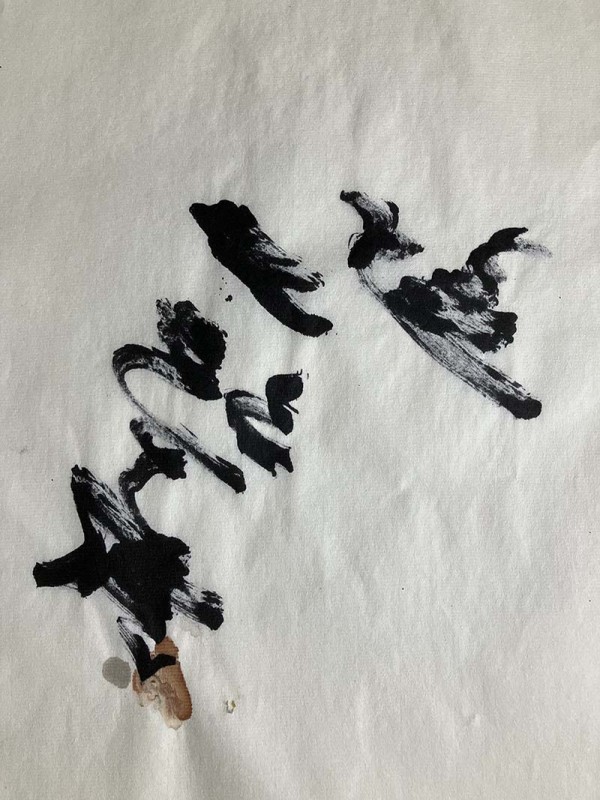

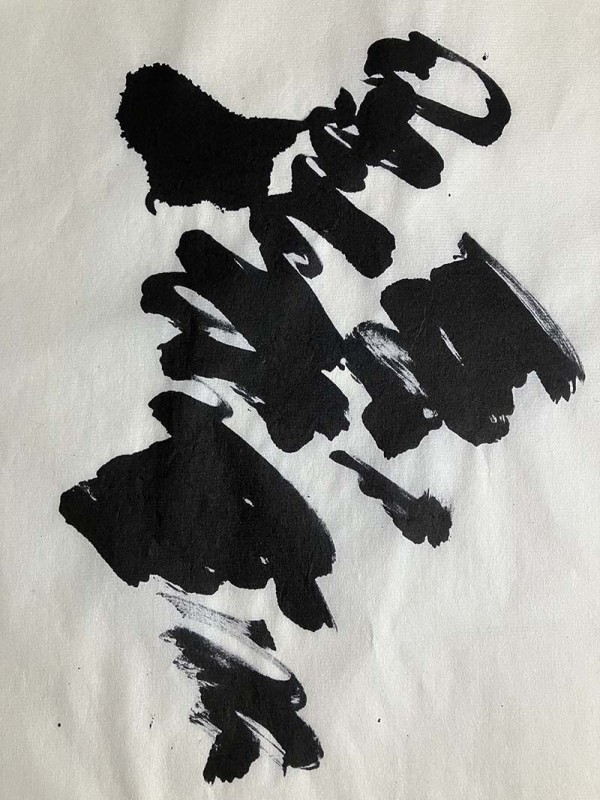

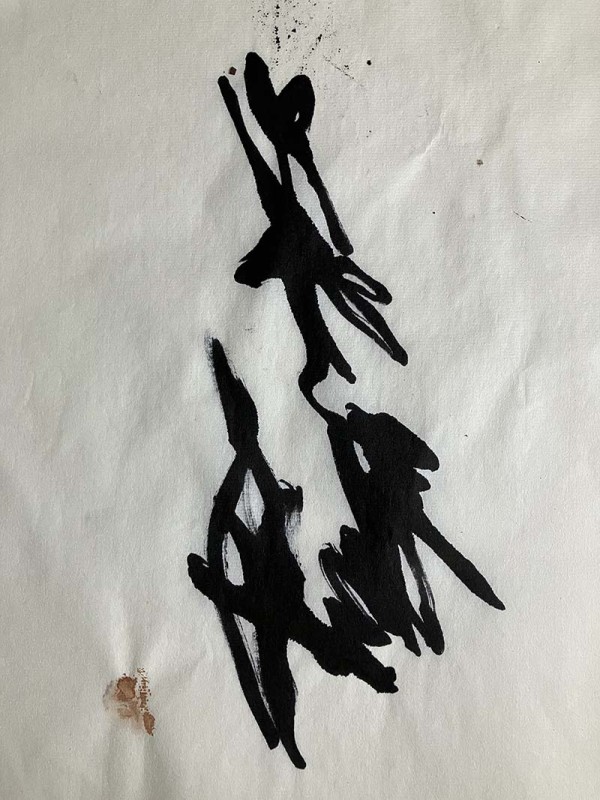

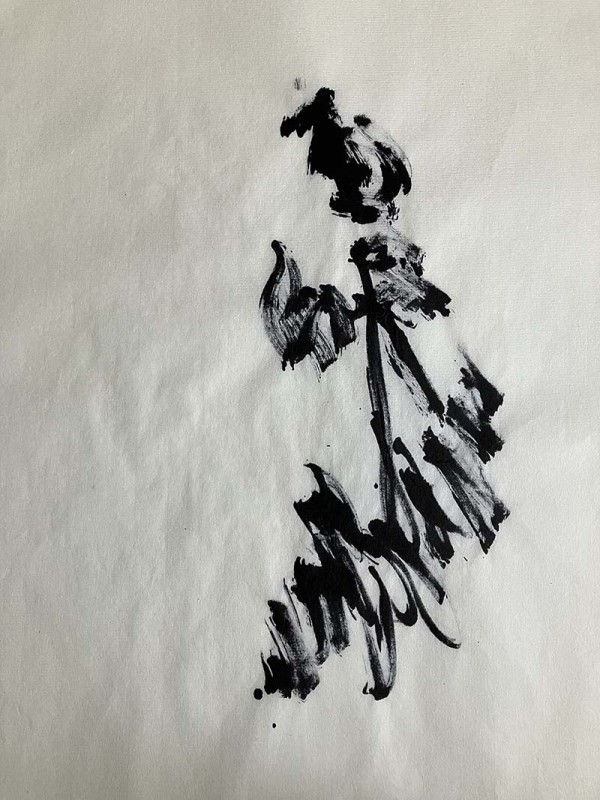

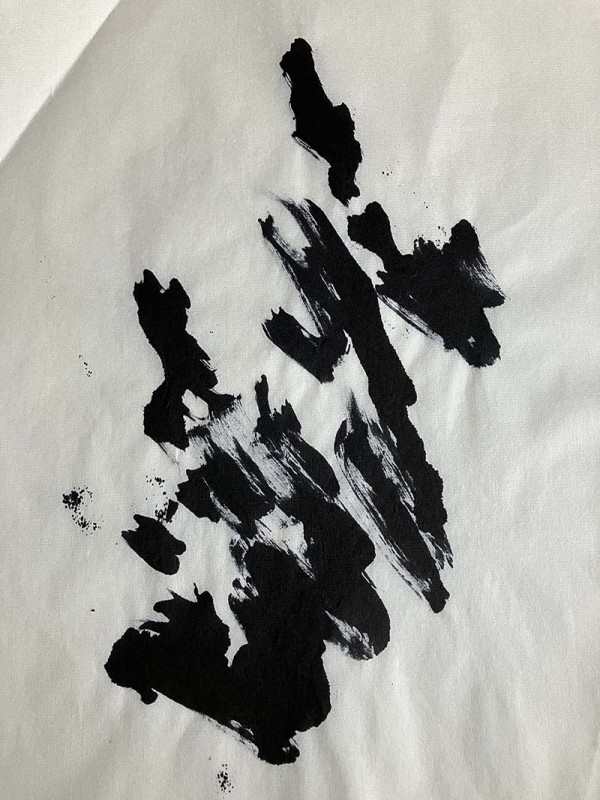

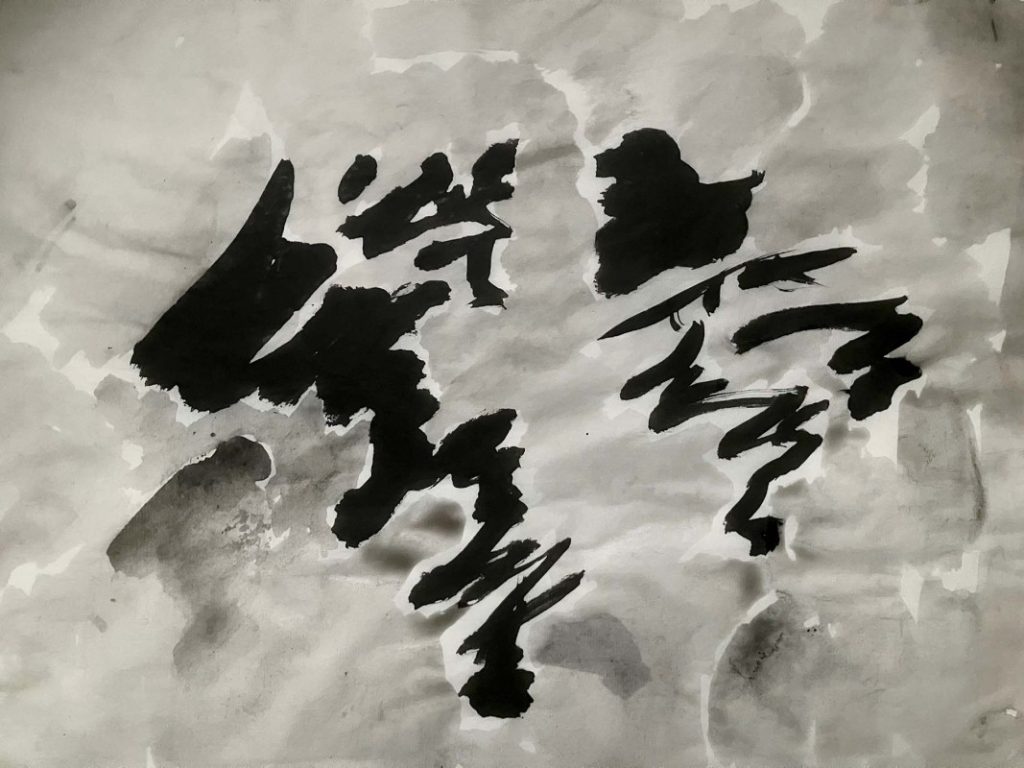

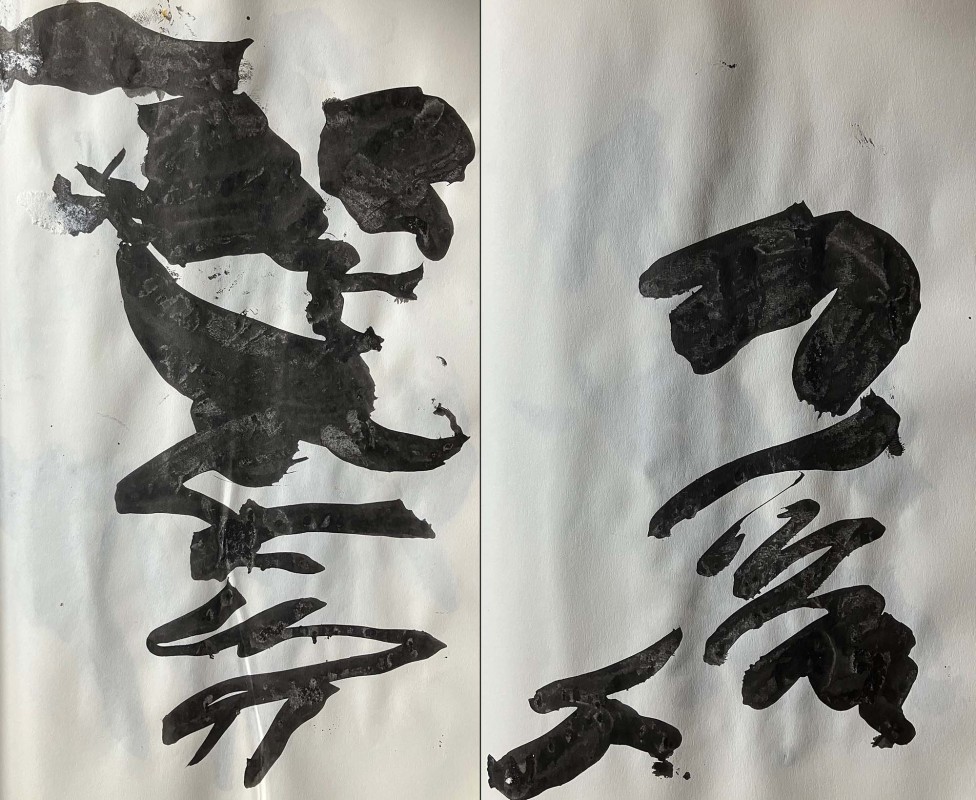

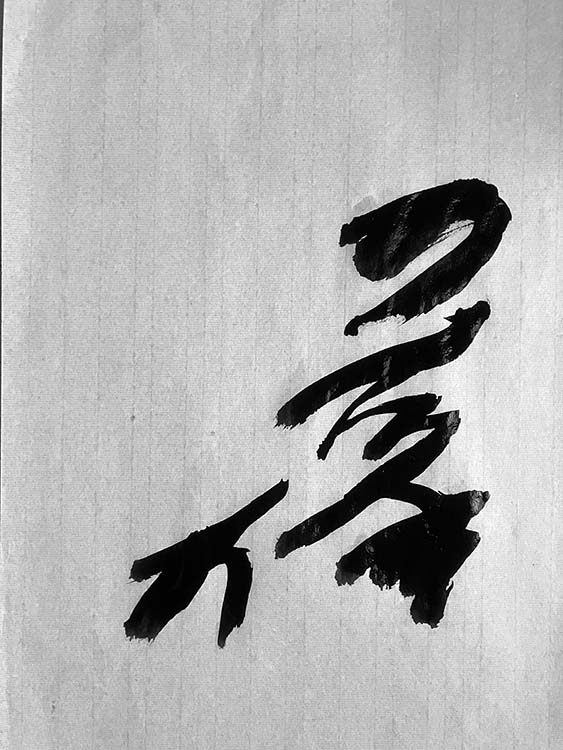

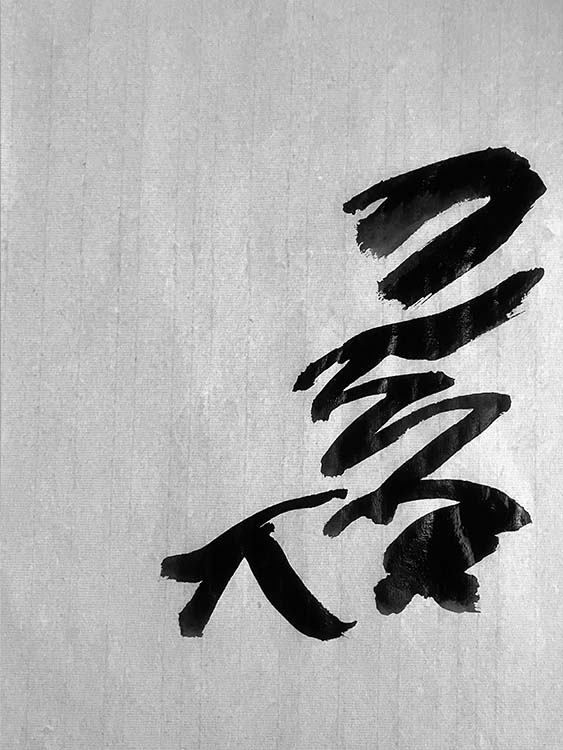

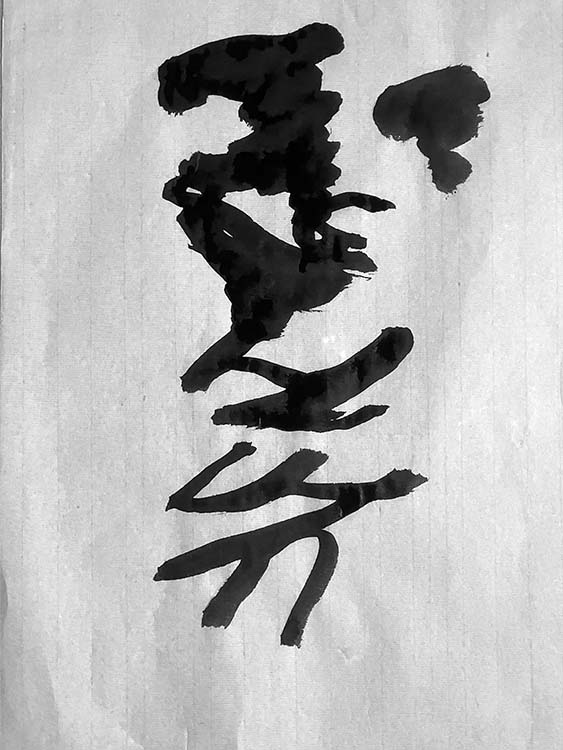

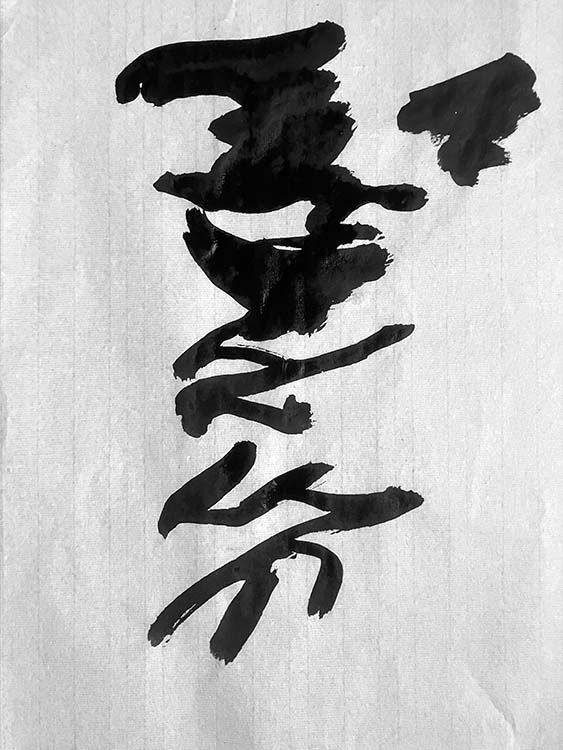

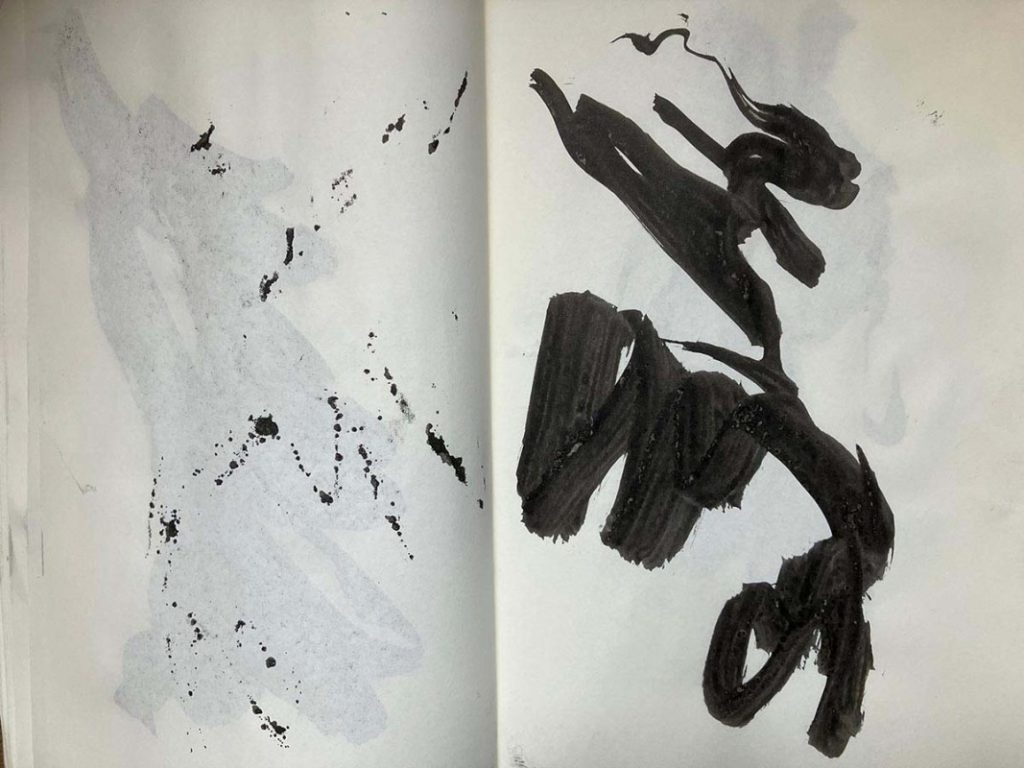

I’m going to be producing some scrolls using the shadow calligraphy I’ve created in the woods and having had a scroll made recently, I’ve been looking at how to take this further, using the whole scroll as an artwork, rather than acting simply as a framing device for the painted character.

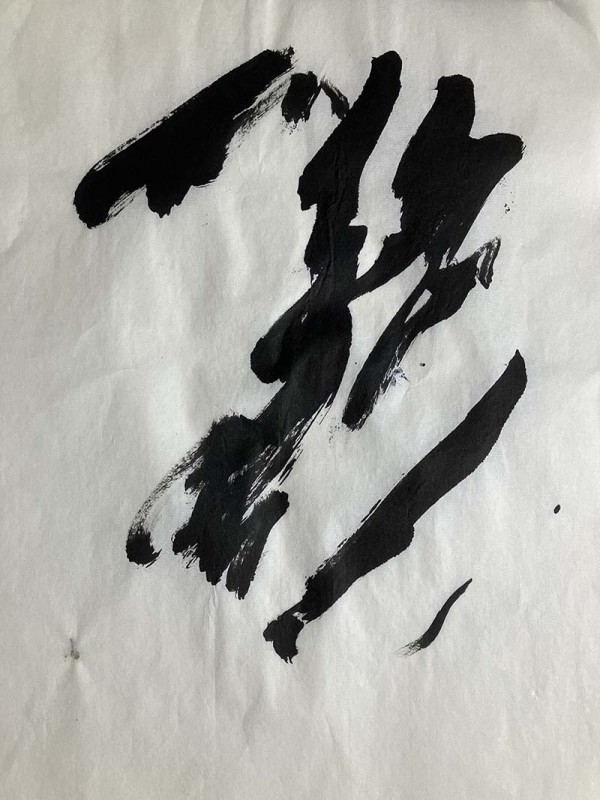

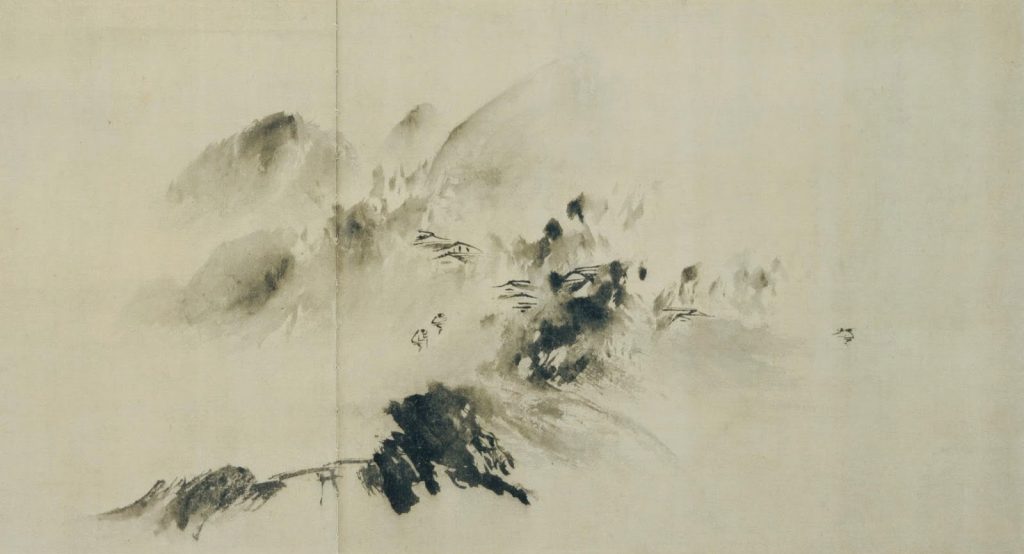

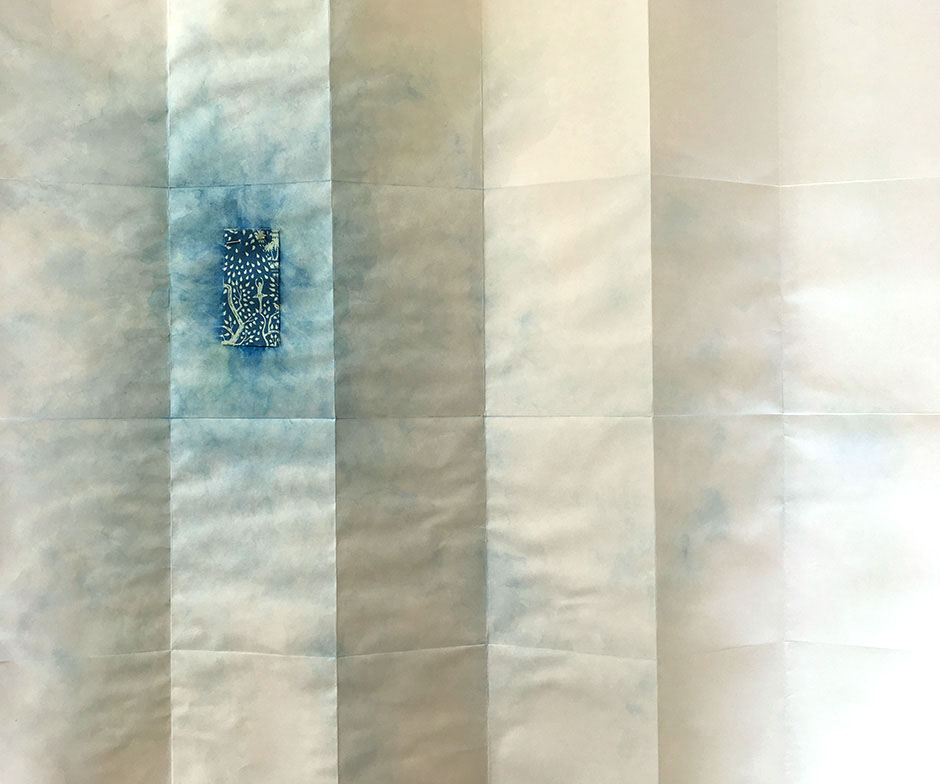

To help with this I’ve been looking at buying a scroll and the image below shows three that I found for sale on eBay.

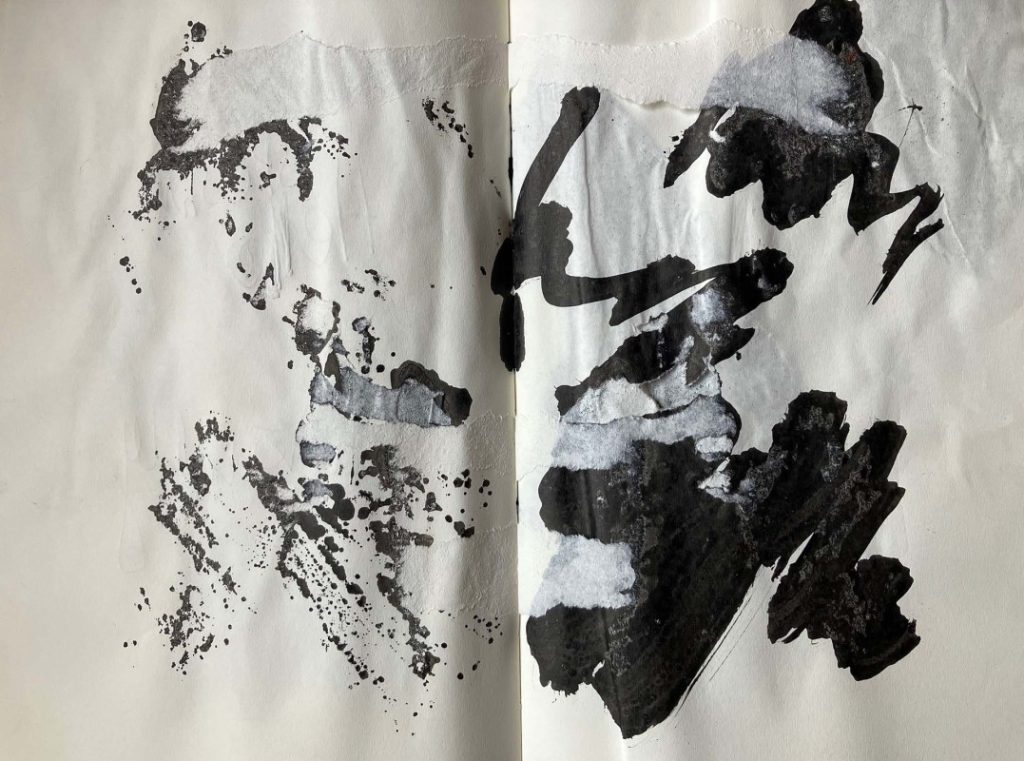

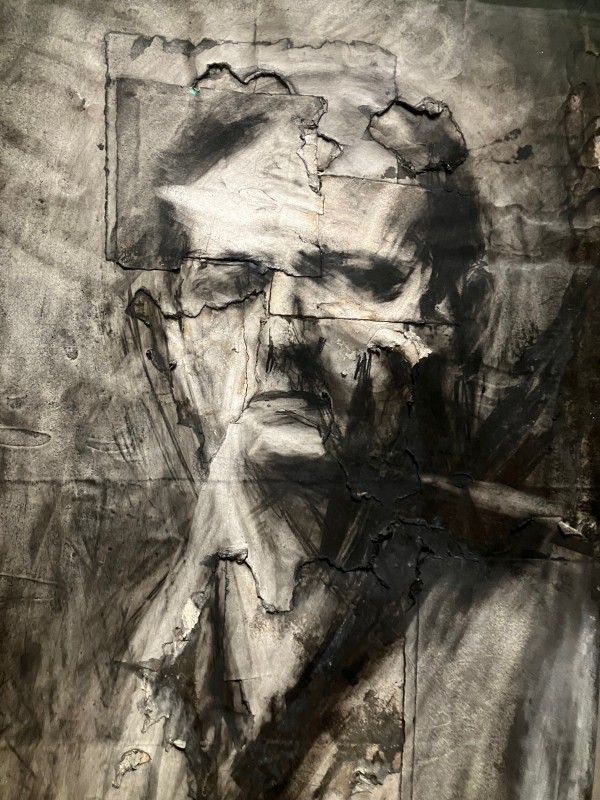

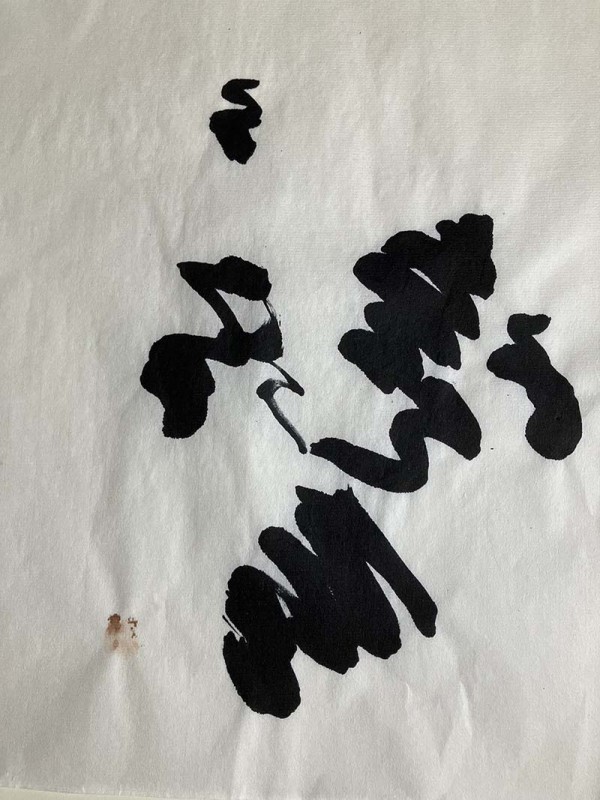

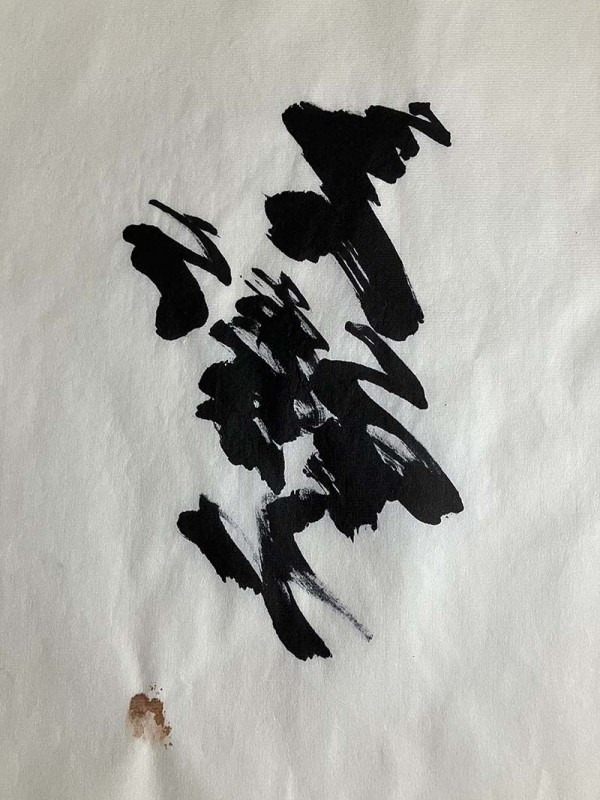

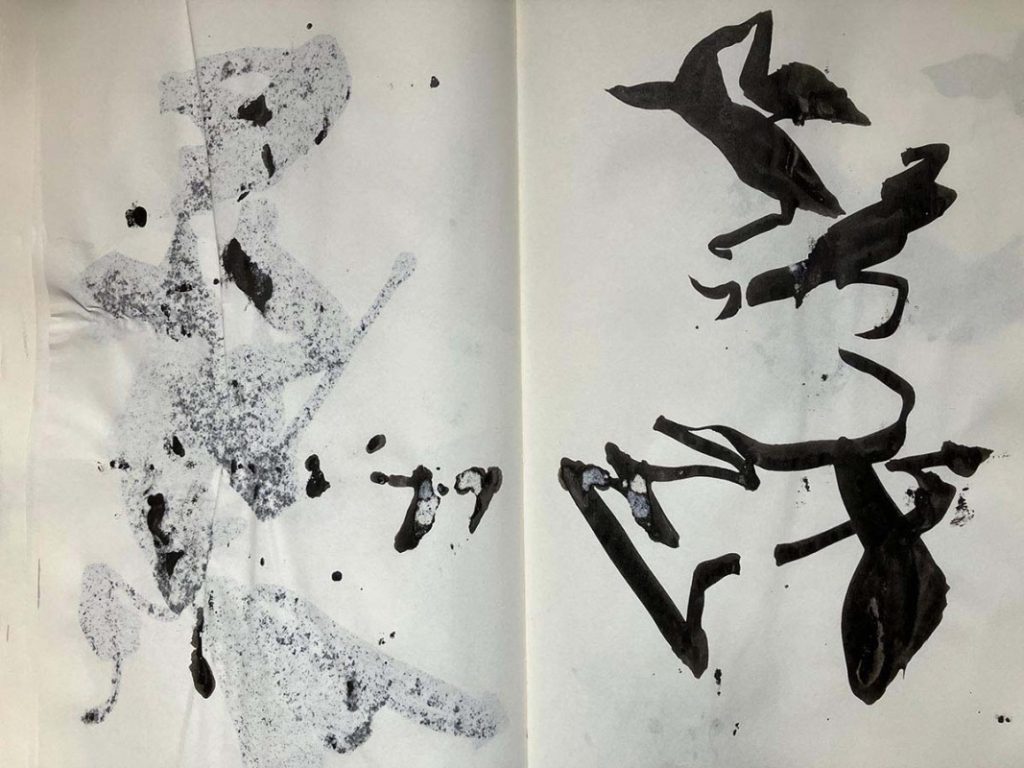

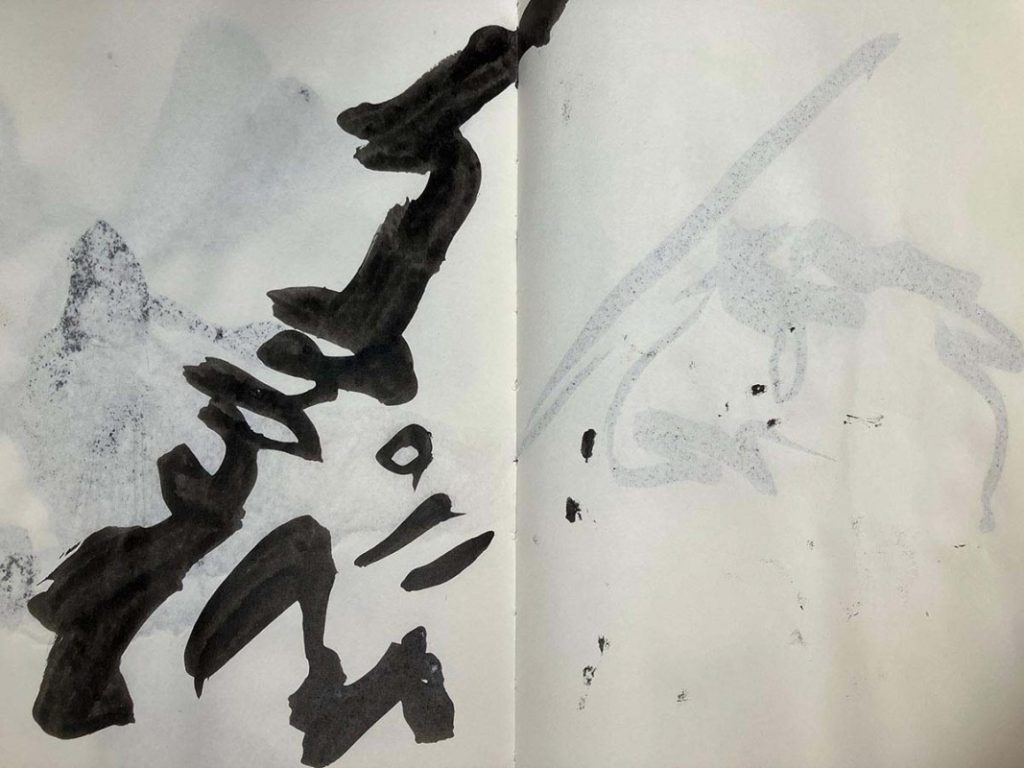

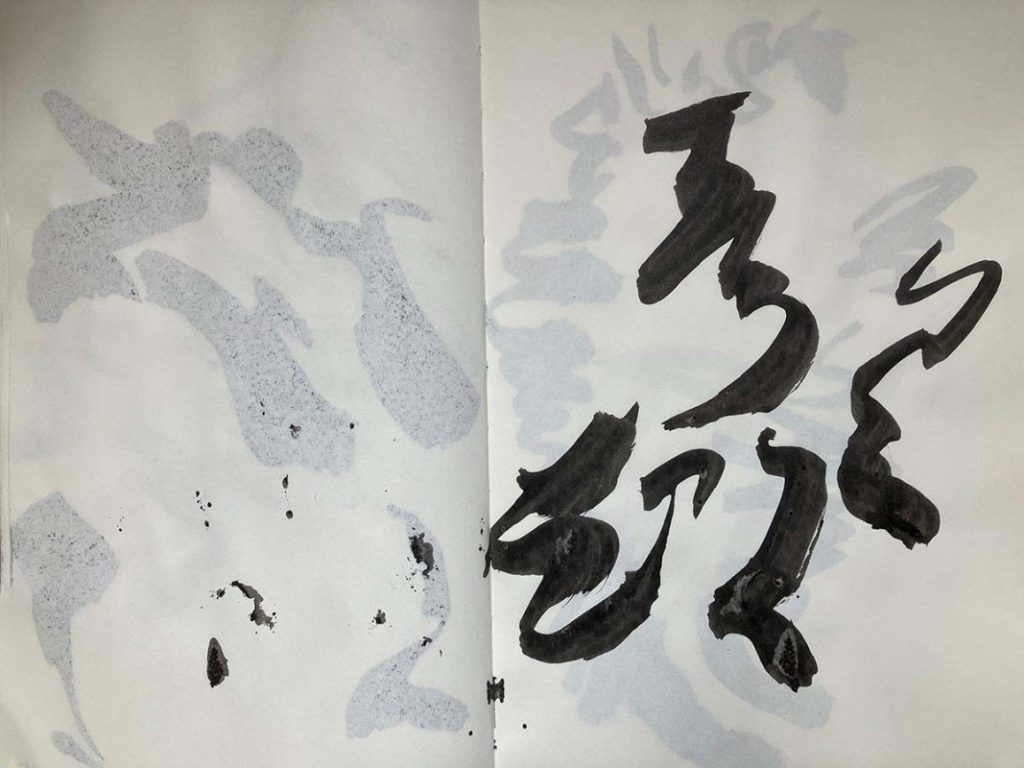

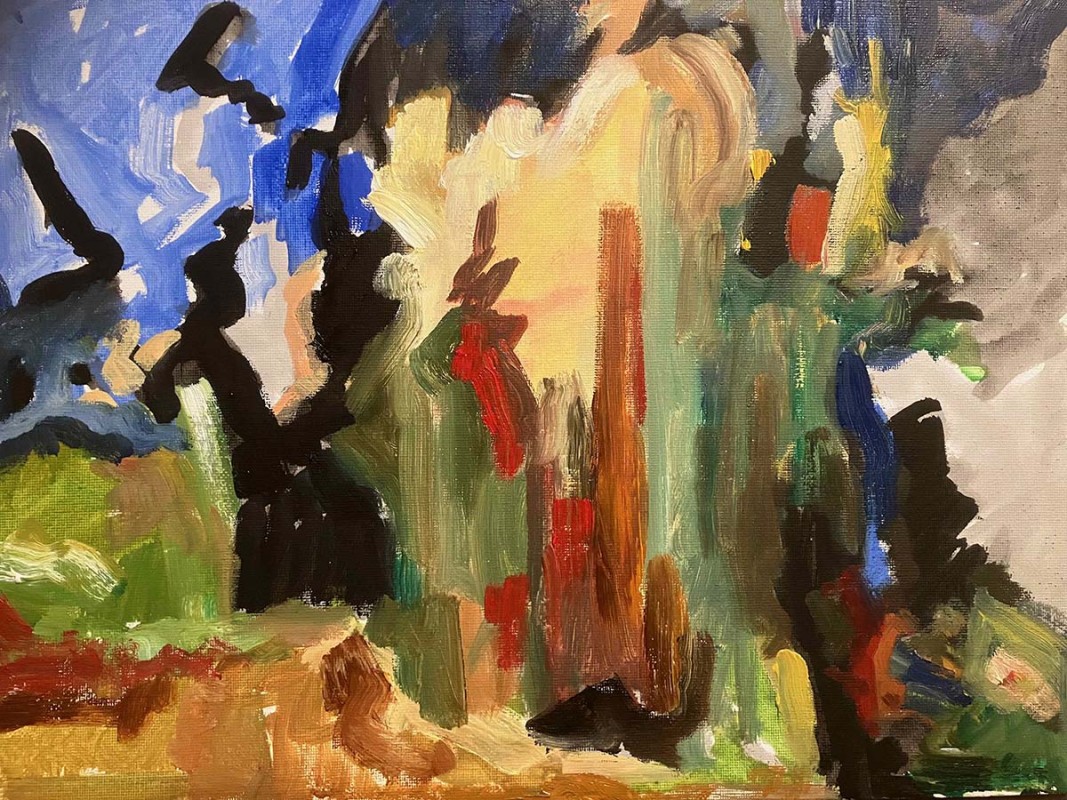

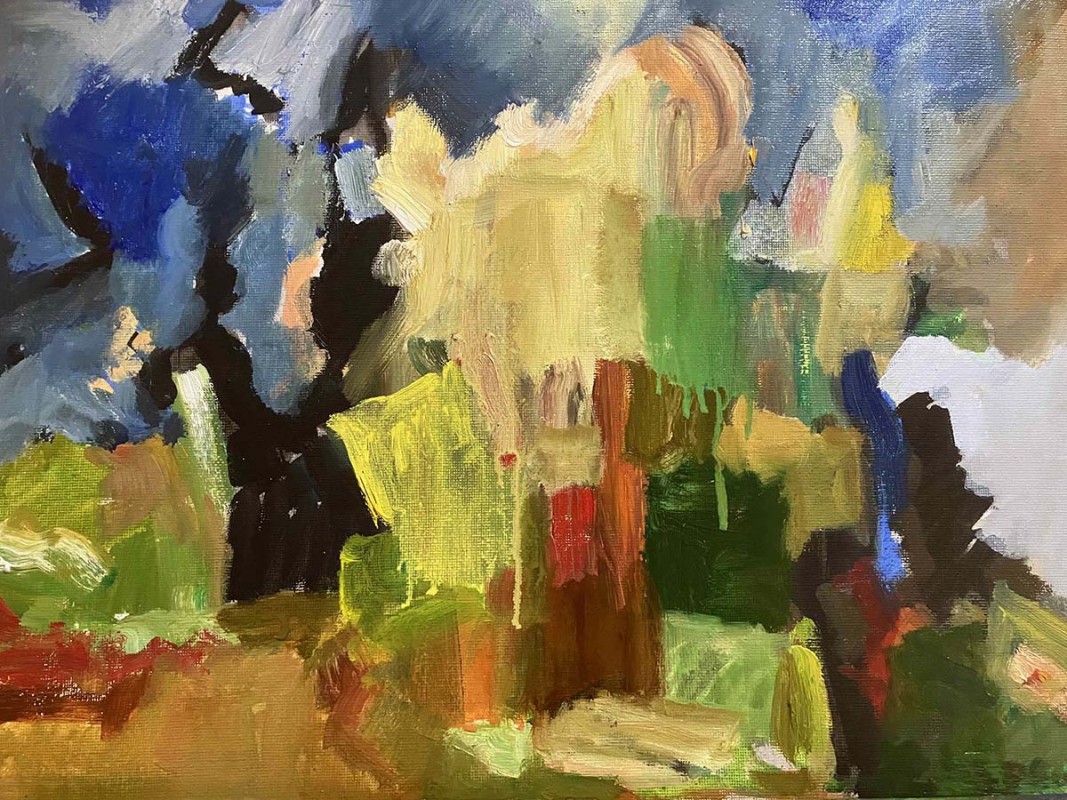

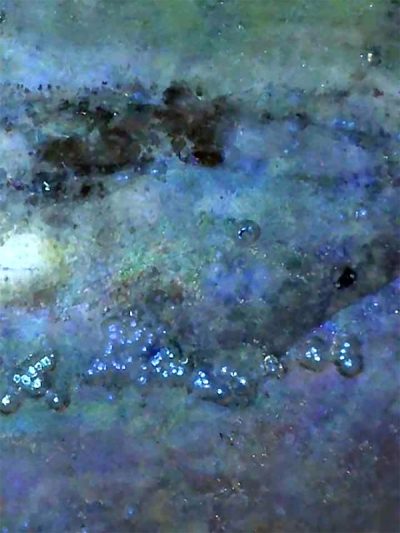

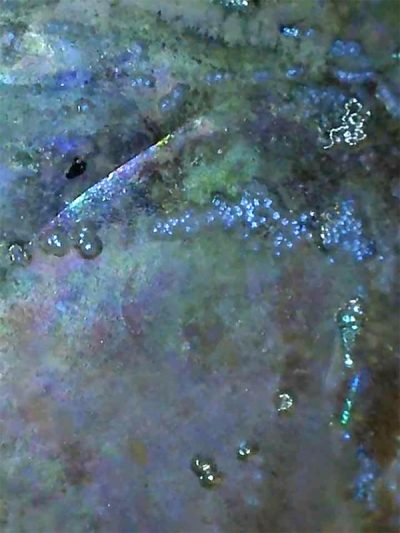

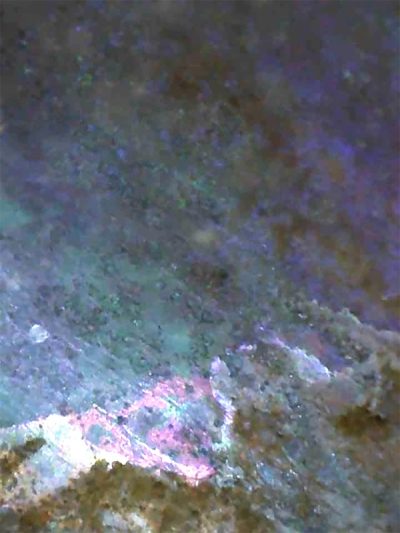

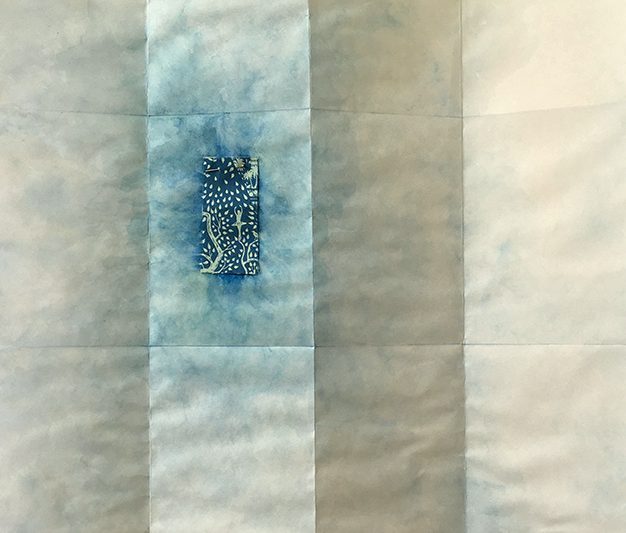

Looking at the material used in these, I was reminded of some work I did a while back using fragments of fabric which I then extended onto paper.

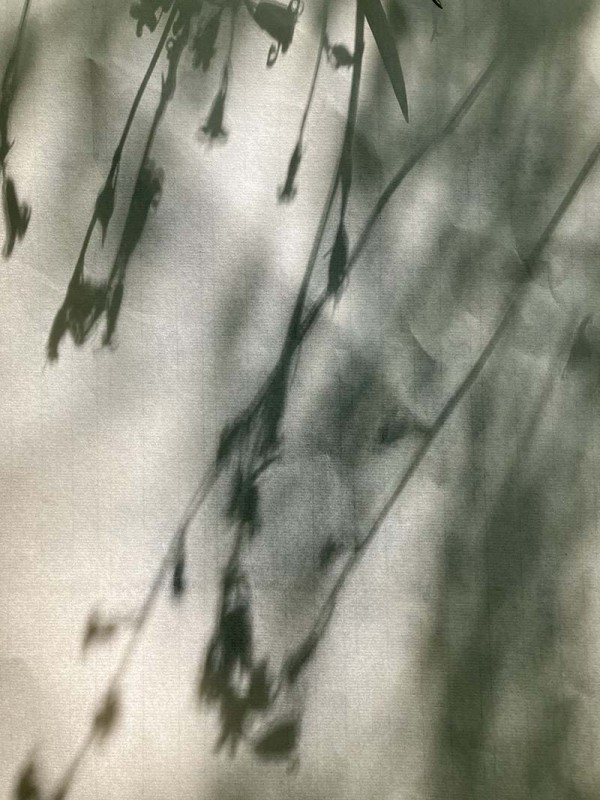

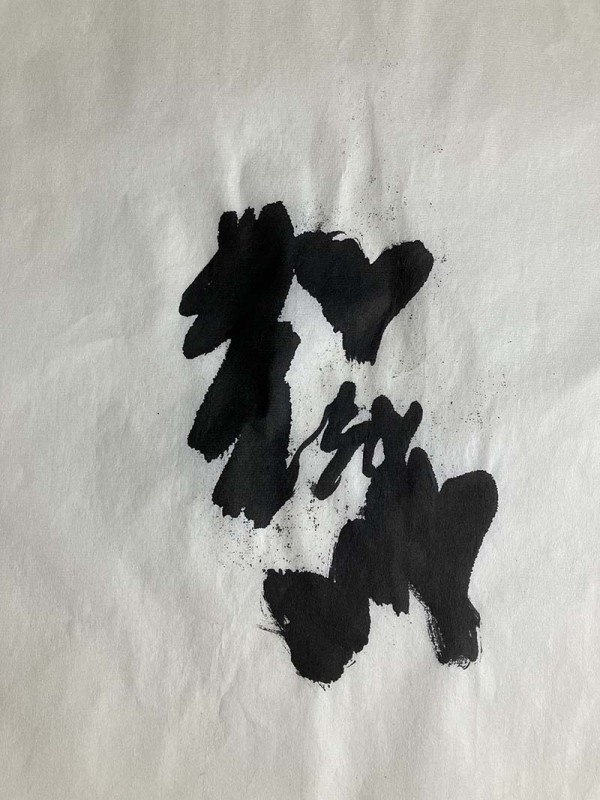

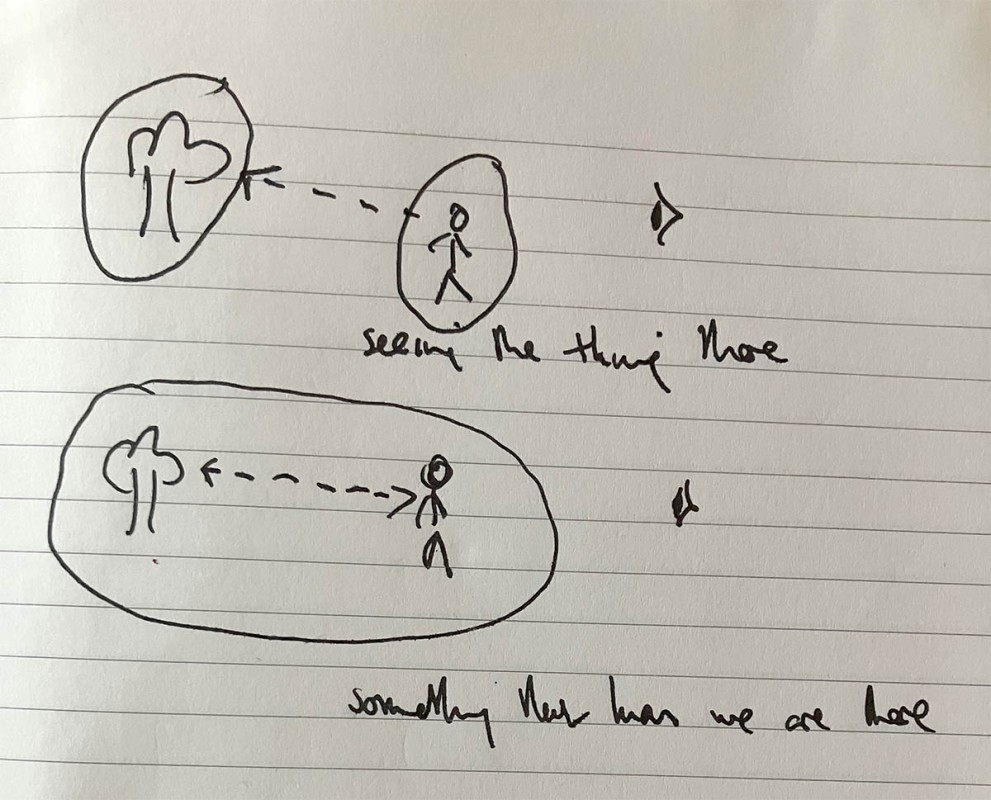

I like the idea of the backing for the painted ‘characters’ incorporating this idea of the fragment which would then extended into the body of the scroll support. This would itself support the idea behind the characters; that they are all that remains of a moment in the woods which we can interpret as a ‘word’, thereby returning, in our minds, to that lost moment in time. The pattern of the fragment in the support might be foliage which which would then be extended across entire support, echoing the idea of the moment being extended in our mind’s eye.

I think this idea would work well both with paper and fabric, so I shall be busy trying these out soon.