Mine the Mountain is listed on Culture24.org‘s list of Must-See Art shows this month. I’m at No.3, just below Richard Hamilton… can’t be bad!

The Answer

For years the answer to a question I’ve been asking myself has been staring me in the face. Its own face is a big ugly one on the cover of a book which I used to have and which I loved to read and play as a child.

I won’t say anymore for now, so again this entry is one that will, for the time being, make sense only to me.

Wordsworth and The Other

On my journey back from Nottingham yesterday, I listened to a podcast of In Our Time about William Wordsworth’s The Prelude. Whilst listening to one of the panel talking (Stephen Gill) I was struck by his reading of a particular passage and what he said about it thereafter. The passage was from Book II of the poem and is as follows:

The garden lay

Upon a slope surmounted by the plain

Of a small Bowling-green; beneath us stood

A grove; with gleams of water through the trees

And over the tree-tops; nor did we want

Refreshment, strawberries and mellow cream.

And there, through half an afternoon, we play’d

On the smooth platform, and the shouts we sent

Made all the mountains ring. But ere the fall

Of night, when in our pinnace we return’d

Over the dusky Lake, and to the beach

Of some small Island steer’d our course with one,

The Minstrel of our troop, and left him there,

And row’d off gently, while he blew his flute

Alone upon the rock; Oh! then the calm

And dead still water lay upon my mind

Even with a weight of pleasure, and the sky

Never before so beautiful, sank down

Into my heart, and held me like a dream.

Stephen Gill said of this passage: “look at the language of this, it’s all about your body being taken over by the outside world, the dead still water lays upon thy mind, the sky sinks down into my heart and the pleasure of it all is a weight.”

I was struck by this passage and commentary as it seems to parallel the notion of the embodied mind; a corporeal consciousness engaging with the world through the physical body.

I bought a copy of The Prelude and read the first few lines which served to illustrate this point further:

Oh there is a blessing in this gentle breeze

That blows from the green fields and from the clouds

And from the sky: it beats against my cheek

And seems half conscious of the joy it gives.

The following passage is a lovely description of the act of wayfaring:

Whither shall I turn

By road or pathway or through an open field,

Or shall a twig or any floating thing

Upon a river, point me out my course.

In a piece I wrote on my website about history, I wrote the following:

In his book The Materiality of Stone, Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology, Christopher Tilley writes: ‘The painter sees the tree and the trees see the painter, not because the trees have eyes, but because the trees affect, move the painter, become part of the painting that would he impossible without their presence. In this sense the trees have agency and are not merely passive objects. Dillon comments: “The trees ‘see’ the painter in a manner comparable to that in which the mirror ‘sees’ the painter: that is, the trees, like the mirror, let him become visible: they define a point of view on him which renders visible for him something that otherwise would remain invisible – his outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence… The trees and mirror function as Other.”’

I am interested in how the landscape remembers the people it ‘sees’ and I find this ‘Other’ everywhere in Wordsworth’s poetry. Again in Book I of The Prelude.

How Wallace fought for Scotland, left the name

Of Wallace to be found like a wild flower,

All over his dear Country, left the deeds

Of Wallace, like a family of Ghosts,

To people the steep rocks and river banks

In Lines Written A Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey, Wordsworth addresses his sister Dorothy with the following words:

Therefore let the moon

Shine on thee in thy solitary walk;

And let the misty mountain-winds be free

To blow against thee: and, in after years,

When these wild ecstasies shall be matured

Into a sober pleasure; when thy mind

Shall be a mansion for all lovely forms,

Thy memory be as a dwelling-place

For all sweet sounds and harmonies; oh! then,

If solitude, or fear, or pain, or grief,

Should be thy portion, with what healing thoughts

Of tender joy wilt thou remember me,

And these my exhortations! Nor, perchance,

If I should be where I no more can hear

Thy voice, nor catch from thy wild eyes these gleams

Of past existence, wilt thou then forget

That on the banks of this delightful stream

We stood together

I like to think of this poem and this passage as addressing nature herself, that great ‘Other’ which remembers those whom she has seen.

Ancient Reflections

I went to the Ashmolean Museum today and found myself literally in the surface of an Athenian, black-glazed hydira (water-jar) dating from around 400 B.C. My reflection in the glaze became for a moment a part of its design and I wondered as I looked at my silhouette, who else had become a part of its fabric over the course of the last two millennia?

Text Rain

The following image is taken from Tom Phillips’ book, Postcard Century. I was reminded on looking at the image of a piece I made called Dreamcatcher and in particular a photograph I took of work in progress.

Future Work

Mine the Mountain 2

This weekend I set up my latest exhibition at Surface Gallery in Southwell Road, Nottingham. It’s a lovely space run by a great group of people (all volunteers) who helped install the show – to them I am very grateful indeed! Below are some photographs of the exhibition. More information on the exhibition can be found on the Mine the Mountain website.

The exhibition runs until 19th March 2010.

Dust Motes II

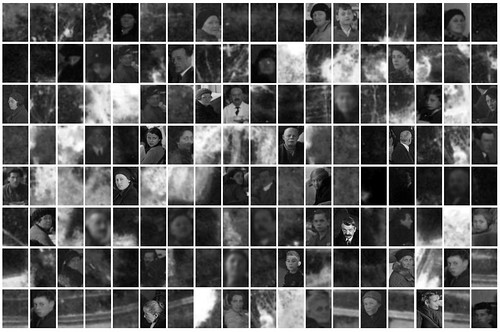

Two photographs taken from the archives of the Czechoslovakian secret police and two photographs from a piece of mine called Broken Toys.

Interesting Link

An English Journey Reimagined

www.guardian.co.uk/books/video/2010/mar/03/english-journey-iain-sinclair-alan-moore

An Act of Imagination

There’s a shop in Paris where I like to go, whenever I am there. In a box you can rummage through a small pile of photographs, miscellaneous images, nothing overly special, but for a few Euros one of them can be yours. That shown below is the last one I bought.

The photograph is small; two and a half by three and a quarter inches. It’s damaged and indistinct; blurred in parts, but nonetheless one can see the interior of a church, within which a small group of women and girls stand facing towards the altar. The photograph was taken from above, perhaps from a gallery opposite the pulpit which one can see on the opposite wall. The pulpit’s draped in material, whether that’s normal or for a special occasion I cannot say. I cannot tell what is going in, but clearly something’s happening beyond the frame of the picture (the world is happening beyond the frame of the picture – as are we, the viewer). As for a date; given the hats, I would say it was taken sometime in the 1920s.

The photograph is fragile. It has the feel of an Autumn leaf, dried and picked from the ground the following Spring. When I hold it in both my hands, my thumbs discover very slight depressions where others have looked before me. The way the paper’s warped, the way that it bends, tells me it’s been looked at many times.

Where the picture contains the trace of someone who was loved, the paper carries the gesture of the lover.

Of course we cannot know this, not for certain. But history is an act of imagination.

Who is the object of his or her attention? My eyes move to the girl at the front, dressed in white or pale colours and wearing a matching hat. My left thumb, in its slight depression almost seems to touch her, mimicking the gesture of the one to whom it belonged. There’s something secret about the image, as if whoever took it shouldn’t have been there, shouldn’t have possessed her. It’s an image that’s meant to be kissed, secreted away in a wallet. Affection has caused the wear in the corner.

She knows she’s being photographed. She knows that someone loves her. She can see in her mind’s eye the gallery behind. She can sense the gaze of her admirer. But then the paper tells me she didn’t turn around, she never returned the gaze. Ever.

A Well Staring at the Sky

The title of this piece takes its name from a passage in Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet;

“We never know self-realization. We are two abysses – a well staring at the sky.”

For me, this quote describes the act of looking at a photograph, at people in the past who are likely no longer with us. I look at them from a time when they do not exist, and they look at me from a time when my existence was wholly unlikely. They are reflections left in the water of the well, and I, for the moment am the person looking in. The portraits in the work are from a single photograph taken in Vienna c.1938. The faces are mixed with images cropped from an aerial view of the Bełżec Death Camp photographed in 1944. History too is a well staring at the sky. Again in the well’s water, we see the sky reflected with some of its stars and all of its gaps. But no gap is truly empty and all the holes in what we call history are full of traces; the residue of a glance perhaps shared between two people.

To see more work from this exhibition, please follow this link.

In Ruins

“A ruin is a dialogue between an incomplete reality and the imagination of the spectator.”

Christopher Woodward, In Ruins

Photograph of Corfe Castle taken during a school trip in 1983.

I first visited Corfe Castle in the summer of 1978 whilst on holiday with my family. I was 7 at the time. I can remember a postcard commemorating the murder of Edward the Martyr (reigned 975-978) a 1000 years before. It’s the first historic place which really captured my imagination, and ever since my mind’s been in thrall to the past. The idea of a 1000 years ago seemed – as it does now – impossible, and in the museum below, in the village of Corfe, I remember staring at a cannon ball dating from the English Civil War, trying in my mind’s eye to picture it, as it was at the time of the siege, moving through the air.

Photograph of me and my brother at Corfe Castle c.1980.

Dust Motes

Mine the Mountain 2 – Poster

For more information, please visit www.nicholashedges.co.uk/minethemountain

Mine the Mountain 2

Postcards are a kind of conversation, inasmuch as they’re a connection between two places; one that’s unfamiliar and one that’s known. That’s not always the case of course, but their form’s a framework – a metaphor – with which I try to engage with the past.; to find its lost, anonymous individuals. ‘The Past is a foreign country’, wrote the author L.P. Hartley in the first line of his novel The Go-Between. Whatever information we receive about that place, whether in writing, an object, a painting or a photograph, it comes like a postcard from a foreign shore.

Postcards are fragments, pieces of a world which has vanished, often carrying information of little or no consequence. In the translator’s foreword to The Arcade’s Project, Walter Benjamin’s ‘monumental ruin,’ we read:

“It was not the great men and celebrated events of traditional historiography but rather the ‘refuse’ and ‘detritus’ of history, the half concealed, variegated traces of the daily life of ‘the collective,’ that was to be the object of study.”

The ‘collective’ is represented in this exhibition by the sheer number of postcards and the pictures which they make when grouped together as a whole. What their component images say, echoes my attempt to find the individual so often subsumed, both in unimaginable numbers and the history which we read in books or know through film and television.

In photographs we often come closest to finding individuals when – ironically – they’re distant, when they’re blurred and unaware of the picture being taken. These are genuine moments of history. With words, it’s often the smallest of details which brings the past alive, for in these parts the whole of the time from which they’re now estranged is immanent.

Tom Phillips, in the preface to his book ‘The Postcard Century’ writes that with postcards:

“High history vies with everyday pleasures and griefs and there are glimpses of all kinds of lives and situations.”

High history sits in every word, even in the ‘x’ of a single kiss. Or the words in the postcard below; prices for Train, Ale and Fags.

A postcard too is often the physical trace of a journey, one connecting the dots from the place in which it was posted to its final destination. But this destination’s never really reached, and as such, a conversation which may have begun 100 years ago, is never finished. We read the words today, written before we’d ever the hope of existing, sent by those who don’t exist anymore.

The images in this exhibition are not ‘genuine’ postcards per se, but they are (for the most part) postcard-sized, inspired by a collection dating from the First World War. It’s the idea of the part (the individual image) as being a part of a whole which interests me and the whole being immanent in the part, just as humanity is immanent in every individual.

A Short Quote

Schopenhauer: ‘The task of art is to turn tears into knowledge’.

Kinaesthetic Empathy

The following text ‘What is Kinaesthetic Empathy’ is taken from the Watching Dance website. Although I’m not an afficionado of Contemporary Dance, I’ve become interested in how aspects of movement and general agency have started to appear in relation to parts of my work and research.

“Spectators of dance experience kinesthetic empathy when, even while sitting still, they feel they are participating in the movements they observe, and experience related feelings and ideas. As dance scholar Ann Daly has argued:‘Dance, although it has a visual component, is fundamentally a kinesthetic art whose apperception is grounded not just in the eye but in the entire body’ (Daly 2002).Spectators can ‘internally simulate’ movement sensations of ‘speed, effort, and changing body configuration’ (Hagendoorn 2004).An important source for the concept of kinesthetic empathy is Theodor Lipps’ theory of ‘Einfühlung’. Lipps (1851-1914) argued that when observing a body in motion, such as an acrobat, spectators could experience an ‘inner mimesis’, where they felt as if they were enacting the actions they were observing.This shared dynamism of subject and object implied the notion of virtual, or imaginary movement.Kinesthetic empathy and related concepts took on particular relevance in the context of modernism, which emphasized the idea that receivers should respond directly to the medium of a work of art (eg. movement rhythms) rather than to a storyline or a subject.In the US, Lipps’ ideas were taken up and developed by the influential dance critic John Martin (1893–1985), who championed the dance of Mary Wigman and Martha Graham. Martin argued that what he variously called the spectator’s ‘inner mimicry’, ‘kinesthetic sympathy’ or ‘metakinesis’ was a motor experience which left traces – ‘paths’ – closely associated with emotions in the neuromuscular system. Sensory experience could have the effect of ‘reviving memories of previous experiences over the same neuromuscular paths’, and also of ‘making movements or preparations for movement’ (Martin 1939).”

The following is a quote from Christopher Tilley:

“If writing solidifies or objectifies speech into a material medium, a text which can be read and interpreted, an analogy can be drawn between a pedestrian speech act and its inscription or writing on the ground in the form of the path or track.”

What I have been researching as part of my work could be described as Kinaesthetic Empathy whereby a person’s being in a place and his/her movement through or around that place is a means of ‘reading’ the ‘writing’ laid on the ground by what Tilley calls the ‘pedestrian speech act’.

Totes Meer

I was watching The Culture Show last night and during a piece on a Paul Nash exhibition at the Dulwich Picture Gallery I was struck by the following painting, Totes Meer which can be seen below.

It shows a heap of German planes – those brought down over England, ready to be sorted so the metal could be salvaged. For Nash, it was a scene to inspire Patriotism, but what interested me – at least initisally – was the fact this scrap heap had been in Cowley, not far from where I once lived.

I am of course interested in the past, the wreckage of the past if you like, and how we can salvage parts to be reused in the present day, so therefore this painting has a great deal of interest for me; not only because of that but because of the scrapheap in Cowley.

Stories

In his excellent book, ‘The Past is a Foreign Country’, David Lowenthal writes:

“Among the Swahili, the deceased who remain alive in the memory of others are called the ‘living-dead’; they become completely dead only when the last to have known them are gone.”

Having read this, I began to think about Henry Jones, my great-great-grandfather who took his own life in Cefn-y-Crib in 1889. For all intents and purposes, he had, until I (and another distant relative) had begun to research him, been ‘completely dead’ in that anyone with a knowledge of who he was would also have passed away. For many years therefore, he would have existed as a name, inscribed on his grave or recorded in various documents such as census returns. He would have been, apparently, nothing more than that.

Now however, he is part of my family tree, ‘reconnected’ – albeit abstractly – to his own loved ones and those who came both before and after he lived. But a list of names, connected or otherwise is only a part of the story. As Tim Ingold writes, in his book ‘Lines – a Brief History‘:

“The consanguineal line is not a thread or a trace but a connector.”

The line connecting Henry Jones to his forebears and descendants tells us nothing about him. As Ingold explains; ‘Reading the [genealogical] chart, is a matter not of following a storyline but of reconstructing a plot.’ What I want, as far as is possible, is the story, the narrative as it was written at the time.

As I wrote in my essay ‘What is History?‘:

“Human beings [Ingold writes] also leave reductive traces in the landscape, through frequent movement along the same route… The word writing originally referred to incisive trace-making of this kind.’ By walking and leaving our reductive traces on the ground therefore… we could be said to be writing or drawing ourselves upon the landscape – writing or drawing our own history.”

It was only when I visited Hafodyrynys in May 2008 that Henry Jones became – for want of an expression better suited to the 21st century – in the words of the Swahili, ‘living-dead’ again. It was only then, as I walked around the village where Henry Jones lived, walking the same roads and pathways, that I began to read – as far as was possible – a part of his story. I knew the dates of his birth and death (I’ve since learned of his suicide) but these are plot points. Only when retold as part of the story do they start to make an impact, and that story can only be read in the places where he walked.

As I walked, I felt as if I was both recording my own story on the roads and pathways around Cefn-y-Crib, whilst reading that of my ancestors, in particular my paternal grandmother, who lived as a child nearby in Hafodyrynys and who passed away a few months after my visit.

A quote from Christopher Tilley’s ‘The Materiality of Stone, Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology’ illustrates this point:

“The body carries time into the experience of place and landscape. Any moment of lived experience is thus orientated by and toward the past, a fusion of the two. Past and and present fold in upon each other. The past influences the present and the present rearticulates the past.”

As we walked (I visited with my dad and girlfriend, Monika), we would phone her up and tell her where we were, and I couldn’t help but feel that we were walking directly within her memories. Time it seemed had collapsed for a while.

As I wrote as part of an investigation in the Old London Road at Shotover:

“Thinking about it now one can take that analogy and think of it [the road] instead as piece of tape which runs and runs and runs and which every step upon it is like the recording head changing the ground, changing the particles on the tape just a little. And just as we record when we walk so we also play, play the ground which passes beneath our feet. We can hear very distantly the thoughts which came before us.”

So how do we read or hear these ‘stories’, written into the ground and the landscape so many years before we were even born? One clue comes in the following extract from Christopher Tilley’s book, ‘The Materiality of Stones, Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology‘.

“The painter sees the tree and the trees see the painter, not because the trees have eyes, but because the trees affect, move the painter, become part of the painting that would he impossible without their presence. In this sense the trees have agency and are not merely passive objects. Dillon comments: The trees ‘see’ the painter in a manner comparable to that in which the mirror ‘sees’ the painter: that is, the trees, like the mirror, let him become visible: they define a point of view on him which renders visible for him something that otherwise would remain invisible – his outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence… The trees and mirror function as Other.”

If we take the analogy of the mirror for a moment and return again to my essay ‘What is History?‘:

“In a famous definition of the Metaphysical poets (a group of 17th century British poets including John Donne), Georg Lukács, a Hungarian philosopher and literary critic, described their common trait of ‘looking beyond the palpable’ whilst ‘attempting to erase one’s own image from the mirror in front so that it should reflect the not-now and not-here…’

Just as the trees function as ‘Other’ therefore, so must the sun, the stars, the clouds, hills, mountains, the sea, rivers and so on. Where we are in the world, where we stand or walk, which direction we are facing are all significant features in this respect. We are what we are because of where we are at a given moment. We exist in relation to [these ‘Others’] and are at any given moment defined by them….

Last year I visited Hafodyrynys in Wales, the village where my grandmother grew up. Whilst standing on top of the hill where she played as a child and across which her father walked on his way to work in the mines at Llanhilleth, I looked and saw a view I knew he would have seen. I found it strange to think that a hundred years ago he would have stood there, just where I was, at a time when I did not exist. A hundred years on and I was there when he did not exist. And yet we shared something in that view. We had both for a time been defined by it. It was as if the view could still recall him and even though it was new to me, that I was nonetheless familiar.”

We are defined by the world around us and as such we might be said to be remembered by that world. But of course over time the world changes and where things disappear, so do, to some extent, memories. We therefore have to fill in the gaps. I once wrote something about this during a residency at OVADA in Oxford in 2007.

“In the film, the visitors to the Park are shown an animated film, which explains how the Park’s scientists created the dinosaurs. DNA, they explain, is extracted from mosquitoes trapped in amber and where there are gaps in the code sequence, so the gaps are filled with the DNA of frogs; the past is in effect brought back to life with fragments of the past and parts of the modern, living world. This ‘filling in the gaps’ is exactly what I have done throughout my life when trying to imagine the past, particularly the past of the city in which I live.”

I appreciate that my metaphors are beginning to stack up a little. However, where we can fill in the gaps with our own experience is where we can begin to see the past as it was when it was the present.

No Man is an Island

I have written a great deal about how I perceive the past and how I use objects and the landscape to find ways back to times before I was born. In my text ‘What is History‘ I conclude with the following paragraph.

“History, as we have seen, [might be described as] an individual’s progression through life, an interaction between the present and the past. It follows, having seen how the material or psychical existence of things extends much further back than their creation that history spanning a period of time greater than an individual’s lifetime is like a knotted string comprising individual fragments; fragments within which – in the words of Henri Bortoft – the whole is immanent. The whole history of all that’s gone before is imminent in every one of its parts; those parts being the individual.”

I was reminded as I read this paragraph – and in particular the last line – of the poet John Donne and the following words taken from his XVII Meditation:

“No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were: any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.”

Having read this, I thought about some of the work I’ve been making for my forthcoming exhibition in Nottingham, Mine the Mountain. Two pieces are maps of invented landscapes, one of which (the first shown below) is based directly on a map I created as a child, the other based on the outline of Belzec Death Camp as seen in an aerial view of 1944.

The Past is a Foreign Country, 2010

The first map, as I have said, is a contemporary reproduction of one I made as a child. It’s therefore essentially a map of an individual – of me, as I was at the time. It is a place that, although imagined, was real nonetheless, one based on fragments of my memory and my perception of the distant past.

Having been to Wales (in 2008) and imagined all my distant forebears walking the various tracks and roads around the village where my grandmother grew up, I realised how I was very much a part of those places and they in turn were part of who I was. I had existed – at least potentially – in those places long before I was born. All those roads, paths and trackways led in the ‘end’ to me. Of course that sounds a rather egocentric way of perceiving the world and its history, but then I’m not suggesting that I am the only intended outcome. Just as my invented world – my map of me – was made of all those bits of the past I loved to imagine as a child (the untouched forests, the unpolluted rivers and streams) so I can see how this foreshadowed my current thoughts on history; how I am indeed (as we all are) a place, one made of all those places in which my ancestors walked, lived and died.

A quote from a source which is of huge importance to me and my work (Christopher Tilley’s ‘The Materiality of Stone, Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology’.)

“Lived bodies belong to places and help to constitute them so much so that the person can become the place (Gaffin 1996). The body is the medium through which we know place. Places constitute bodies, and vice versa, and bodies and places constitute landscapes. Places gather together persons, memories, structures, histories, myths and symbols.”

Alongside the second map I will be showing a piece of text taken from the diary of Rutka Laskier describing what appears to be an imaginary landscape, though one perhaps based on memories of family holidays to Zakopane, Poland. She was a child when she died in the Holocaust and by putting the two maps together, I want to reflect on the numbers of children who perished, as well as illustrating how within each child – within everyone – the whole of humanity is immanent.

John Donne’s words serve to illustrate this sentiment further still. No man, woman or child is an island. So whilst I have created two maps of individuals, through Donne’s words we can see how these islands comprise pieces of everybody else.

If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- …

- 31

- Next Page »