And so to the crematorium

We’ll make our way again. This empty place

Full of names, shards like glass from broken

Window panes, and rain like thorns on roses.

To the waiting room where no-one sits

Where all the clocks have stopped to rub their hands

Where mourners recount the hour of the toll

And one by one swallow nothing whole.

Through the gates the headlights come, bearing down

On everyone who waits. Black slick night,

Shadows in no hurry for today or

Days that have passed. A nervous laugh

Hovers above the breathless chimney stack

A graceful scar upon the tumbling sky

The bird floats high by dint of searching eyes

And dives. Gone as if it never was at all.

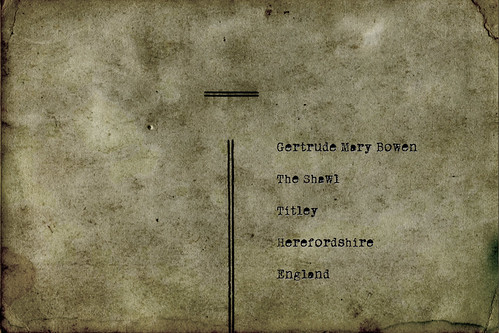

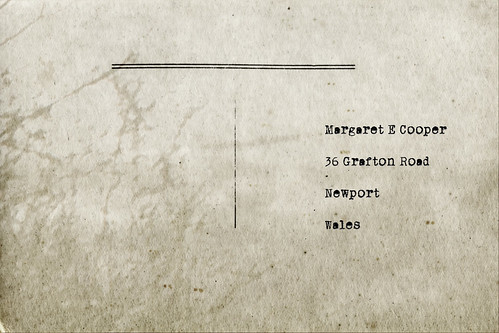

We greet old friends and those still unknown

With half-suppressed expressions. Like uncertain

Lovers in love’s first encounter; a chain-gang shackled

By the things we should remember, we walk

Towards the chapel. We follow the pipes

That bellow death in gentle slumbered tones

And take our seats with strangers; our only

Child in common has seen the flame and blown.

We hide in the order of service

Words of hymns that nobody knows, rising from

The page like cat-pawed moths, flitting round a

Hopeful bulb. Then at last the curtains close

To hide the cheap illusion. Some close their eyes.

Some stand with hands clutching their tears

Like summer drinking rain. Then all go home

Beyond the flowers, until it’s time again.