Photographs taken at installation sites (Deadman’s Walk and Botanic Gardens) this weekend.

Mine the Mountain – Installation

On Thursday and Friday this week I installed my two pieces at the Botanic Gardens and Deadman’s Walk as part of my forthcoming exhibition, Mine the Mountain. What was interesting for me was how, even though I’d planned the work and visualised it in my mind, it appeared so different when actually installed – how new connections between the works were made due to the effects of things one wouldn’t have accounted for, such as, for example, the sun. It was also gratifying for me how members of the public, particularly in Deadman’s Walk were interested to know what I was doing, and more importantly, interested in the work and how it fits with the rest of the exhibition. Being able to speak about things directly is one thing of course, having the work do it for you is another.

Quite a few people knew the name ‘Deadman’s Walk’ but few people knew the history behind it, and it was nice to be able to share my knowledge with people directly. Some clearly knew the name and its origins and assumed before I’d even said anything that the names on the plaques were names of Jews; interesting when one considers that the origins of my research were in Auschwitz.

Having completed the work at Deadman’s Walk I walked to the Botanic Gardens to check on the installation there, and on seeing it again, I was struck by how it worked ‘alongside’ the work in the walk, how the two pieces echoed one another. The sun too gave the piece an added dimension, with the veiled mirrors every now and then catching the sun and for a split second flaring up before dying back down again.

It was as if these ‘glares’ were voices, calling out from the past, albeit briefly, asking to be remembered. They were also in my mind metaphors for our own brief lives in contrast the to the unimaginable span of time we call History. And here there is a connection between this piece and that which I will install in the Town Hall Gallery this week, ‘Stars and Very Lights’ which features 150 faces taken from crowd scenes photographed by Henry Taunt in Oxford. Very Lights are flares fired from a pistol, a term I used to reflect the quickness of life set against the backdrop of ‘non-existence’. In this sense, the sun catching the mirrors echoes that completely – something I hadn’t considered before installing the work.

Oxford and Wales

Given my Welsh ancestry and my recent visit to Wales I’ve been looking for something which might give me another way into the subject, a link perhaps between me here in Oxford and my ancestors there is Wales. I decided to look at some Welsh myths, being as I am interested in old stories, and so I bought a book; ‘The Mabinogi and Other Welsh Tales.’ I won’t discuss at any length the book (translated and edited by Patrick K. Ford) or explain what the Mabinogi is, but will simply present a piece of text from one of the tales; ‘Lludd and Lleuelys’. In that story one finds the following:

“Some time after that, Lludd had the island measured in length and breadth; the middle point was found to be in Oxford. There he had the earth dug up, and in that hole he put a vat full of the best mead that could be made, with a silk veil over the surface. He himself stood watch that night. As he was thus, he could see the dragons fighting. When they grew weary and exhausted, they fell onto the screen and dragged it down with them to the bottom of the vat. After they drank the mead they slept; as they slept, Lludd wrapped the veil about them. In the safest place he could find in Eryri, he secluded them in a stone chest. After that the place was called Dinas Emrys; before that it was known as Dinas Ffaraon Dandde, He was one of three stewards whose hearts broke from sorrow.”

The reason why this piece of text interested me in particular is probably obvious; the fact that in a book of Welsh Mediaeval myths, Oxford is mentioned. There’s also some thing in the text which gives me a way in to the subject, into possible ideas.

Abingdon Road

One of my favourite drawings is that made by a German-born, Oxford-based artist called John Malchair, who lived and worked in the city in the late 18th century. The drawing shows a view of the Abingdon Road as it appeared in 1770 with the strange and imposing edifice of Roger Bacon’s study in the foreground – a building that was demolished nine years later – and the familiar, extant structure of Christ Church College’s Tom Tower behind.

There’s something beguiling about the image, depicting as it does the city long before the car, before its expansion into the suburbs when still surrounded by fields and meadows. It’s a quiet almost pastoral scene in which I feel I can hear the birds and feel the sun on my face. I can almost hear the quietude, contrasting it with the sounds I would hear today if I stood in a similar position; indeed, it’s an image in which I am constantly contrasting, moving back, to and fro between the past and the present.

This contrast between the past and present is what I experience as I research my family tree and this image I’ve lately realised embodies some of my recent thinking and research. My great-great-great-great-grandfather, Samuel Stevens, born in 1776, lived and worked as a tailor on St. Aldates in Oxford, a street which is in effect a continuation of Abingdon Road as it moves towards and connects with Carfax in the city centre. I like the fact that he is contemporary with this image and would have been alive (if only a small boy) when Roger Bacon’s study was still standing.

On the other side of my family tree, on my father’s side, my great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, William Hedges lived and worked in Abingdon, a town in which his line lived until George Hedges moved to Oxford sometime around 1869 when he married Amelia Noon, daughter of Charlotte Noon, murdered by her husband Elijah in 1852 (see ‘A Murder in Jericho‘). It’s very likely of course that both these lines (the Stevens’ and the Hedges’) continued back in those same places (Oxford and Abingdon) for further generations, and I like the fact that in this image by Malchair, and in a sense in the building he drew, is a connection between the two. Not only that, there is a connection between my past and my present, as if that connection might be found in the road between Oxford and Abingdon.

Finally, in a project I started some time ago (6 Yards 0 Feet 6 Inches) I make mention of a survey by John Gwynn, carried out in 1771 in which all the residents of Oxford are listed along with the measurements of their properties. It’s a fascinating document in its own right, but if Samuel Stevens’ parents lived in Oxford just a few years before his birth, they would be listed in that survey. Flicking through there are a number of Stevens’ and I can’t help but think one of them is my ancestor.

Feedback

Continuing in my research into the murder (or manslaughter as it transpired in the Assizes) of Charlotte Noon by her husband Elijah, I looked – in the Oxfordshire Record Office – at the original burial records for the Parish of St. Paul’s which includes Jericho where the Noons lived in Portland Place, Cardigan Street. I had my suspicions that Charlotte Noon would have been laid to rest in St. Sepulchre’s cemetery off Walton Street and in the records I found this to indeed be the case. I could even see the original plot number ‘G7’ which unfortunately today, won’t help in the identifying of her grave.

Despite this, yesterday I went a second time to St. Sepulchre’s and began to look again for the grave of Charlotte Noon. Maybe, just maybe, it would be one of those which had defied the passage of time and which could still be read – even if with fingers, but I knew this was unlikely to be the case; for one thing, I assume, as they were not a wealthy family, that the grave stone would be have been rather modest and less likely to survive the last 153 years; indeed this seems to be the case. Many of the graves have melted into the ground and only their outlines in the depressed turf indicate their presence. Nevertheless, there was something very poignant about walking around the cemetery knowing that I was in the immediate vicinity of her last resting place – there was, for those moemnts – a physical link between us.

I have walked around the cemetery on several occasions before, but was always oblivious to what it contained; now, as I walk, the whole place feels very different, as indeed does Jericho as a whole.

The cemetery along with streets Jericho are a part of my ‘geographic biography’. Writing about the piece of work I’m showing at the Botanic Gardens – 100 Mirrors (Dolls), I borrowed a quote from the artist Bill Viola, who wrote:

“Looking closely into the eye, the first thing to be seen, indeed the only thing to be seen, is one’s own self-image. This leads to the awareness of two curious properties of pupil gazing. The first is the condition of infinite reflection, the first visual feedback.”

This ‘feedback’ is precisely what I experience when I walk in these places – indeed any places where I know named ancestors of mine once walked – as if we are for that moment, both walking at the same time.

North Star Public House

In the Oxford Journal reports into the murder of Elizabeth Noon by her husband Elijah, it’s stated that:

“He had been drinking at the North Star public House, in St. Giles’s, on Saturday night; that house is kept by the daughter of her [Elizabeth Noon, daughter of Elizabeth and Elijah] uncle Mr Thomas Noon, who paid his men there, and where her father, who worked for him, received his wages which were 20s.”

Like dozens of pubs, the North Star public house has long since vanished and is one which I have never heard of. However, on researching the pub in the library today I discovered the following information:

“North Star public house, 3 Broad Street. Very few records of this pub, but seems to have been mainly licenced by women; Isabella Gittins in 1832 and Mrs. Marsh in 1871. Not known when it closed, but the premises could have been the house of W.B. Yeats the poet while he lived in Oxford. The whole of the site was demolished in 19828 and became Boswell’s department store [which it still is].”

On another site, Headington.org the following information about the North Star is given:

Among the building which had to be demolished to make way for the present Boswell’s was… the eighteenth-century North Star pub. At the time of the 1851 census the North Star pub was occupied by John White and his wife and four young children, while in 1881 the publican was a widow, Mrs Eliza Smith, who lived there with her two sons.

According to the newspaper, the pub was, in 1852, run by the daughter of Thomas Noon, brother of Elijah Noon. It is interesting however, that the surname ‘White’ is the maiden name of Elizabeth (Charlotte). To understand the report I decided to take a look at the census for 1851.

Indeed, John White was the publican so one can only surmise that between the date of the census being taken and the date of the murder, the tenancy was taken over by Thomas Noon’s daughter, the cousin of Elizabeth Noon (daughter). Looking again at my family tree however, I could see clearly that the Thomas Noon I had down as being Elijah’s brother would be too young to have a daughter running a pub at that time. Therefore I could again surmise that I had made a mistake and that Thomas Noon must be older (it made sense too given that Elijah worked for him).

Searching the records again, I found a Thomas Noon, born in Burton Dassett in 1796 and living in Oxford in 1851. I knew this was Elijah Noon’s older brother. Looking at the census details I could see also that he was a builder and was married to to a woman called Ann who was born around the same time. They both lived in Little Clarendon Street.

As far as things stand, I haven’t found the name of their daughter, or any of their children for that matter, but it’s interesting how I’m using Ancestry not only to find people to whom I am directly related, but to track and place people in a particular moment in time – an event, which in this case happens to be a murder.

A Murder in Jericho

Through my research these past few months, I’ve uncovered several tragic stories surrounding the lives and deaths of my ancestors; John Stevens, my great-great-great-uncle, spent 17 years incarcerated in Moulsford Asylum, Berkshire until his death in 1888 at the age of 51; Jonah Rogers my great-great-uncle, was killed in the second battle of Ypres on May 8th 1915 at just 22 years of age; and Henry Jones, my great-great-grandfather took his own life in Cefn-y-Crib, Wales in June 1889, whilst, as his death certificate records, ‘temporary insane’. Death certificates can, as I discovered with that of Henry Jones tell one a great deal about a person’s life as well as their death, and knowing that my great-great-great-grandmother, Charlotte Noon, had died in Oxford at the age of just 33, I was intrigued to see how she’d met her end, assuming that it was as a consequence of disease.

Having received the certificate in the post however, I was stunned to see the cause of death given as follows:

“Wilful murder bythe said Elijah Noon, the husband of the deceased.” Place of death, “Portland Place, Cardigan Street, St. Thomas’, Oxford.”

I must admit it took a while for the fact to sink in and questions such as how he had killed her began to demand answers. But there were other questions too arising from my research which didn’t seem to fit with the facts as presented by the certificate. If Elijah Noon had, as the certificate stated, wilfully murdered his wife in May 1852, how was it he married Sophia Kinch in December 1854? Surely in those days, if you were guilty of murder, you were hanged?

I decided the next phase of my research would be to look at local papers for the time – namely, Jackson’s Oxford Journal in which I assumed I would find some mention of the case. The next issue following the date of the murder was that published on Saturday 8th May 1852 in which I found a very lengthy report on the murder, the inquest and the subsequent hearing at which Elijan Noon was committed for trial at the next Assizes.

As with the stories I’ve previously mentioned, my ancestors in this case were, in reading the report, certainly brought my to life, even in the retelling of what was a terrible death. Reading their words; “Oh, good God Almighty what shall I do?” “Pray let some one come for I shall die,” I found myself hearing them speak. “Oh my dear boy,” some of the last words of Elizabeth (Charlotte) Noon to her eldest son Elijah. Of course the account is tinged in places with a degree of Victorian melodrama, and at times that which to the modern reader, might seem absurd understatement (“oh dear, what shall I do?”) but the sincerity of the writing is evident and indeed compelling enough to get a sense of the whole tragic affair, the drama not only of the murder itself, but the impact it had in Oxford as a whole.

In the final paragraph of the piece, under the heading “Examination of the Prisoner by the City Magistrates” the words of Elijah Noon, a man “undone” by his actions, say it all.

“The prisoner was then asked by the Mayor if he had anything to say? when he replied ‘I have nothing to say, gentlemen.'”

One can almost hear his tone of voice, see him standing with his head bowed, his whole world and that of his family turned completely upside down. Committed to trial for the wilful murder of his wife, he must have supposed he would hang.

In stories such as this, names become people. Parents and children become more than just past facts in a family tree and the last line of the report illustrates this clearly:

“The announcement [commital for trial at the next Assizes] increased the distress of the prisoner which had manifested throughout the investigation and the parting with his son and daughter was of the most painful nature.”

I have made as best I can from the two prints of the report in Jackson’s Oxford Journal, a PDF copy which is available to download.

So given the dire position in which my great-great-great-grandfather found himself in May 1852, how was it that he lived to marry Sophia Kinch and father seven more children before his death in 1889? Returning to the library I turned again to Jackson’s Oxford Journal. I had thought at first to try and look at the Assizes records but these are held at Kew. I also tried to find the dates of the Assizes held in 1852 but to no avail. However, knowing that there were three Assizes in the year including one in summer, I assumed that Elijah’s trial would take place soon after his appearance before the magistrates at which he was committed for trial.

In the same newspaper I eventually found notice of the Oxfordshire Summer Assizes and the trial of Elijah Noon. It was to take place at 9 o’clock on the morning of Thursday 15th July and in the edition for the 17th July, a full report was given. Again I have created a PDF of the report, but have transcribed a little of it below.

“The trial of Elijah Noon for the murder of his wife, Elizabeth Noon, was fixed to take place at nine o’clock this morning, and by that time every part of the Court was crowded. The prisoner on being placed at the bar, looked very ill, and appeared to feel his position very acutely. Mr. Cripps and Mr. Sawyer were engaged for the prosecution, and Mr Pigott and Mr. Huddlestone for the defence.

Mr. Cripps opened the case by adverting to its painful character, a husband being charged with the wilful murder of his wife, and that it was rendered the more painful because the principal witness in the case as the daughter of the prisoner. Mr. Cripps then detailed the facts of the case, as given in the evidence, and concluded by saying that he felt assured that after they had heard all the evidence, the defence, and his Lordship’s summing up, they would return such a verdict as would be satisfactory to their own consciences and to the public.

Elizabeth Noon, the daughter of the prisoner, was then examined, and was about detailing the facts, when the prisoner: fainted, and was obliged to be taken out of Court. He looked ghastly pale, and his daughter burst into tears, and a more painful and distressing scene has rarely been witnessed in a Court of Justice. The trial was delayed for nearly half an hour, and as soon as the prisoner had revived, he returned into Court, and the case proceeded.”

It is no wonder Elijah Noon looked so ‘ghastly pale.’ He had killed his wife, spent two months in the city gaol and had been separated from his children. Furthermore he was staring at the gallows. The judge in the case had already directed the jury that “no amount of provocation given with words could have the effect of reducing the crime from murder to that of manslaughter,” and this it seems to me was all he could really rely on. “Great allowances must certainly be made for the infirmities of human nature, and when death ensued by means which did not show actual malice, then, in most cases, the crime would be that of manslaughter; but short of that, and if the provocation given were only in words, and death ensued, then the party must be considered as guilty of murder.”

Yet despite the odds seemingly being stacked against him, Elijah Noon was found guilty of the lesser charge of manslaughter and sentenced to two years imprisonment with hard labour. Bizarrely, at the same Assizes, two men on trial for stealing a pair of trousers were given 7 years transportation due to it being their second offence.

Further to studying the newspapers, I was interested in discovering the location of Portland Place. I know Cardigan Street which is listed as being part of the address in the newspaper and on the death-certificate, but Portland Place has disappeared since then. On looking at a map of 1850 however, I found that Cardigan Street continued into Portland Place, whereas today it is all Cardigan Street.

Having studied the map, I walked to Cardigan Street, the layout of which has changed a great deal since that time, but the part of the street which was Portland Place still exists, and walking down there, even though the houses have all changed and the views completely different, I still felt a chill run down my spine.

We are, as I’ve often said, a product not only of everyone that went before us, but everything they did. Anything different and we would not be here. It felt strange then to think that I was only able to walk down that street because, in some small part, of the terrible incident which happened there over 150 years before.

Connections

This evening I began working on an idea I’ve had for a while which incorporates the World War 1 postcards I was given by Tom Phillips. The idea was to show these postcards on a wall but with only a few the right way round i.e. showing the portrait (they are all portrait postcards of soldiers, most individual, some with other people). The rest would be displayed reversed showing either writing or, as is mostly the case, nothing – they would just be blank. I wasn’t sure how this would look and so I began putting the postcards up on my bedroom wall and fairly quickly I could see that the postcards, displayed in this way had an impact.

There was something about the blank postcards which was particularly resonant and the more I looked, the more I could see what it was that leant them this quality. On most of the blank postcards there is a motif running down the centre of the card (dividing the address from the text). These lines are of various designs, some very simple, others more elaborate. I decided to scan a few which can be found below.

For me these motifs have something of the grave about them, perhaps because they are each shaped a little like a crucifix, and they reminded me of some of the memorials I had seen in the Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris.

And as I started making connections, I thought of the X paintings and those I discussed in a previous entry – Black Mirrors and thought about how these marks could be incorporated into a work just like the symbol of the ‘X’.

I also thought how these various motifs/symbols resembled the botanic labels I’ve had made, each engraved with the name of one of my ancestors such as that of Henry Jones (below).

And finally, one last connection between the motifs and a work I made in November 2006, soon after a visit made to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

X (Mine)

I have completed a painting (oil and graphite on canvas, 120cm x 80cm) entitled ‘X (Mine)’ inspired by what I have discussed in previous posts and the profession of my Welsh ancestors; my great, great-great and great-great-great-grandfathers, namely, mining. Below are a couple of images of the work.

What interests me about these works is the fact that they are reflective surfaces and as such one can see a version of oneself (albeit shadowed and indistinct) in the painting itself. This is particularly interesting for me in relation to what I wrote yesterday about Black Mirrors.

Black Mirrors

The black and white veils in question are those with which the 100 mirrors I will exhibit at The Botanic Gardens will be covered. At the moment I’m still unsure as to which to go for. The black veils are the most obvious in terms of the meaning they generate, black being the traditional colour of mourning in this country. White however is the traditional colour of mourning in Jewish culture (so I understand) and a 100 mirrors veiled in white and placed in a grid formation would have the resemblance of a military cemetery which would tie in with the work I’ve done on World War 1 in that they would look a little like a military cemetery. However, having recently read a ‘chapter’ in Bill Viola’s book, ‘Reasons for Knocking at an Empty House,’ there seems to be a case for looking at the black veils again.

In the following passage, Viola discusses the eye and the black mirror of the pupil:

Socrates (describing the Delphic inscription ‘gnothi seauton’): I will tell you what I think is the real advice this inscription offers. The only example I find to explain it has to do with seeing. … Suppose we spoke to our eye as if it were a man and told it: “See thyself” . . . would it not mean that the eye should look at, something in which it could recognise itself?Alcibiades: Mirrors and things of that, sort?Socrates: Quite right. And is there not something of’ that sort in the eye we see with? … Haven’t you noticed that, when one looks someone in the eye, he sees his own face in the center of the other eye, as if in a mirror:’ This is why we call the centre of the eye the “pupil” (puppet): because it reflects a sort of miniature image of’ the person looking into it… So when one eye looks at another and gazes into that inmost part by virtue of which that eye sees, then it sees itself.Alcibiades: That’s true.Socrates: And if the soul too wants to know itself, must it not look at a soul, especially at that inmost part of it where reason and wisdom dwell? …This part of the soul resembles God. So whoever looks at this and comes to know all that is divine – God and insight through reason – will thereby gain a deep knowledge of himself.

The black pupil also represents the ground of nothingness, the place before and after the image, the basis of the “void” described in all systems of spiritual training. It is what Meister Eckhart described as “the stripping away of, everything, not only that which is other, but even one’s own being.”

In ancient Persian cosmology, black exists as a color and is considered to be “higher” than white in the universal color scheme. This idea is derived in part as well from the color of the pupil. The black disc of the pupil is the inverse of the white circle of the Sun. The tiny image in “the apple of the eye” was traditionally believed to be a person’s self, his or her soul, existing in complementary relationship to the sun, the world-eye.

There is nothing brighter than the sun, for through it, all things become manifest. Yet if the sun did not go down at night, or if it were not veiled by the shade, no one would realise that there is such a thing as light on the face of the earth… They have apprehended light through its opposite… The difficulty in knowing God is therefore due to brightness; He is so bright that men’s hearts have not the strength to perceive it… He is hidden by His very brightness.

Al-Ghazzali (1058-1111)

So, black becomes a bright light on a dark day, the intense light bringing on the protective darkness of the closed eye; the black of the annihilation of the self.

Fade to black…

[Silence]”

Through reading this passage, my question as to whether to choose black or white veils for the mirrors was answered and a title suggested for the piece. These mirrors have always served to represent the individuals of the past and our reflections ourselves in the present. They are an attempt to see ourselves as those in the past once saw themselves, a real as we are today. When Viola writes how the closer he gets to have a better view into the eye, the larger his own image becomes, thus blocking my view within, I can take this as being analogous with the difficulties faced by my attempt at seeing individuals in the past where my view, the closer I look is necessarily blocked by my own self (although of course the theme of my work has been to know past individuals through knowing oneself).

This passage also reminded me of a passage from Rilke’s ‘Duino Elegies’ where in the Eight Elegy he writes:

“Lovers – were it not for their loved ones

obstructing their view – they come near it

and are amazed… As if by some mistake,

it opens to them, there, beyond the other…

But neither can slip past the beloved

and World rushes back before them…”

Kisses

Following on from my previous two entries regarding ‘Xs‘ (the signature of the illiterate, a secret location marked on a map), I wanted to look briefly at another use of the mark, that of course being the kiss. I was prompted to do this whilst selecting a number of World War One postcards for a new project website; www.8may.org – a project I hope to carry out next year. Most of the postcards are blank, but on a few there is some writing; the scrawl of a soldier or a more recent label, ‘Mum’s uncle.’ for example. One particular card however took my interest for it contained the mark I had recently been applying to my paintings. In my most recent versions of the ‘X’ paintings (those which have been obliterated by graphite powder) I have been scratching the symbol into the dust whilst considering the many anonymous miners who lost their lives deep underground at the time my great, great-great and great-great-great grandfathers were working in the pits of South Wales.

As I’ve written before, Rainer Maria Rilke wrote that those who die leave their names behind as a child leaves off playing with a broken toy. Those who died in the mines left their names underground; most would not have known how to write them, doing instead what my ancestors did and marking documents only with an ‘X’. And many of those men from the 19th century have all but been forgotten, their names discarded, swept away like Rilke’s broken toys. Even their graves might be lost, their remains buried and marked with an ‘X’, secrets known only by the earth itself.

The Xs on the postcard above are also marks of anonymity. We know they are kisses but we don’t know who they’re for or who gave them. But we know they are symbols of a relationship which once existed, whether between lovers, friends or relations; someone loved someone else. Many of those who fought in the Great War never returned home – all that did return were a few words on a postcard; and ‘Xs‘ – farewell kisses as they came to be. Hundreds of thousands of men not only lost their lives, but they have no known grave. Many too lost their names altogether. These Xs on the postcard therefore become symbols for their future anonymity, their unknown graves; their lost names.

And the Xs which I’ve scratched into dust on my paintings also become a kind of farewell; a broken name, a secret location in time. They also become a farewell kiss to the world.

X, II

Having worked some more on what I have come to call my ‘X’ paintings, I realised there was something interesting in the contrast between the rough, physical paintwork, and the crosses marked on the canvas in pencil, which appear almost spoken by comparison. Perhaps this contrast was all the more appreciable after what I’d written earlier in the day regarding the suicide of my great-great-grandfather.

The crosses, barely distinguishable in the scraped and painterly landscape call to mind how nature can overwhelm us; not only in its beauty and its tempests, but in its age, which, in many respects, is as much a storm as any hurricane. At the moment of death, the world ceases to exist, as if all the storms of a lifetime are condensed into a dying breath. In this reversed storm, the living stand outside in the eye, whilst the dead are collapsed like shacks; stars imploding at the centre of the universe. And the ‘X’ becomes a marker on the landscape, of what was once but is no more; an absence marked by a presence.

How does a man who cannot write his name, leave his farewells as he contemplates the taking of his own life? The repeated mark-making of Xs on the canvas call to mind my drawings of Auschwitz-Birkenau. There, having considered my own non-existence (death), I was through the act of drawing confirming my life and my existence. I was also, through the rapidity of the drawing, trying to capture the present – the moment; the gap between the past and the future, the interval of the shutter’s release.

The Xs on the canvas therefore are in some ways like these drawings; they are confirmations of existence, not of many people, but of one person.

Recalling how these paintings began, as images concerned with Jonah Rogers, my great-great-uncle, I looked again at the landscape which inspired them – or at least the photographs of this landscape.

Jonah Rogers was killed in the Second Battle of Ypres, and the white of the buildings amongst the vivid green of the landscape called to mind the white gravestones of military cemeteries.

They also reminded me of another project on which I am working: Deckchairs, and it is with deckchairs that I am turning to again a regards my painting of this subject, using them as canvases. Having placed them on the wall of my studio, the effect they had was strong. They seem to become instant memorials, their shape and their very essence denoting the human, or in this instance, presence through absence.

A Suicide in Cefn-y-Crib

Back in the spring when I visited Hafodyrynys with my Dad and my girlfriend Monika, we found ourselves – whilst clambering over what my grandmother has always called the ‘Mountain’ – in the company of a farmer, who, with his two sheepdogs, took us on a short tour of his land overlooking the village. He was a man who having been brought up in the area knew that part of the world intimately, and who, as he traced the blue horizon with his hand, reeled off a list of villages resting amongst the hills and fields rolled out below. As we looked over towards the town of Llanhilleth, where my great-grandfather, Elias Jones, had worked as a miner, I couldn’t help but imagine him standing there 100 years before, looking at the same villages and reeling off the same names. Down below, in Rectory Road, he would see the house in which he lived, and in which also lived my grandmother as a child.

Elias Jones died of lung disease in 1929 at the age of 47, caused as a result of breathing in coal dust down the mine in which he worked. He was buried in the churchyard at Cefn-y-Crib, where his wife, Mary Jane, would be buried 40 years later. Also buried in the same churchyard, as we saw that day, was Elias Jones’ father, my great-great-grandfather, Henry, who died in 1889 at the age of 49 when Elias was just 7 years old.

We could see the churchyard from the brow of a hill as we stood in the company of the farmer and his dogs, and in between, a scattering of buildings, vivid and white against the green of the fields, made darker for a moment by the looming presence of clouds which gathered around us as if to experience a view which they would know for only a very short time.

It was as we looked that the farmer pointed to one of the buildings and explained how in December the previous year a young woman was found hanged inside. It was a story which seemed at odds with the beauty of the landscape – a landscape which, nevertheless, just as it had shaped the existence of my paternal family, had shaped the death of this young woman.

In amidst the fields, the seemingly empty barns and houses, and bordered by the forests which clung to the hills surrounding us, one could feel very small and insignificant. In a place such as this one’s awareness of self is augmented, or at least, one’s awareness of individuals. Indeed, of all the people I have researched so far, the two which to me are perhaps the most clearly defined are my great-grandfather, Elias, and my great-great-uncle, Jonah Rogers, who was killed in 1915 in the second battle of Ypres. Perhaps this is in part because of the place in which they lived (and in which that day I was standing), not so much because it’s changed so little, but because its shape, its beauty and its timelessness, serve to delineate the individual better than any city.

I’d always heard that one of my ancestors on the Welsh side of the family had been killed in a mining accident, but I’ve never found anything to even vaguely corroborate the story. Of course accidents were common as my grandmother recalled, remembering how blinds would be drawn in all the windows when another body was brought back up to the surface. Having seen Henry Jones’ grave, I decided to obtain a copy of his death certificate to see if perhaps he – having died young – had been killed in an accident of some kind. As it turned out, the truth was indeed tragic, but for altogether different reasons.

It took me a while to decipher the spider-like writing of the registrar, but suddenly it hit me; cause of death, “suicide while temporary insane,” place of death; Cefn-y-Crib.

Ancestry

I’m very pleased to announce that my forthcoming exhibition, Mine the Mountain, will be sponsored by Ancestry.co.uk.

I have been researching my family tree for almost a year now and in that time have used Ancestry to search thousands of records (census returns; births, marriages and deaths etc.) to build what has now become quite an extensive tree with roots stretching back to the mid eighteenth century. And although most of this research has been carried out alone, through using the Ancestry website I have been able to join forces with a relative (a second cousin) who I have never met and who lives on the other side of the Atlantic in Canada. He had already made good progress on one line of my family (that of my maternal grandmother) and through the website, I was able to merge much of that information into my own research (and indeed, share with him my own first hand knowledge of people he’d never met).

Using the website I made very quick progress, discovering hundreds of people, some of whom had been completely forgotten, swallowed up by time and almost lost to the past altogether. And it was in response to this idea of the anonymous mass, that what had started as a hobby became an integral part of my artistic practice.

I have always been interested in history and the past was always going to feature in the work I wanted to make and much of my work over the last two years has stemmed from a visit I made to Auschwitz-Birkenau in October 2006.

As with many historical and indeed contemporary traumas (whether ‘man-made’ or natural disasters), one of the most difficult things to comprehend at Auschwitz (and indeed with the Holocaust as a whole) was not only the sheer brutality and inhumanity of the place, but the scale of the suffering experienced there. How can one possibly comprehend over 1 million victims (6 million in the Holocaust as a whole)? The only way I could even begin to try, was to find the individuals amongst the many dead; that’s not to say I looked for named individuals, but what it meant to be one.

One of the many strategies I used to explore the individual was that of researching my own past; not just that of my childhood, but a past in which I did not yet exist.

Using the Ancestry website I began to uncover names, lots of names which seemed to exist, disembodied in the ether of cyberspace like the names one reads on memorials (such as on the Menin Gate in Ypres), and I was reminded all the while I searched of a quote from Rainer Maria Rilke’s poem ‘The Duino Elegies,’ in which he writes that on dying we

“…leave even our name behind us as a child leaves off playing with a broken toy…”

It is interesting that in looking back on our lives and beyond, we inevitably pass through our own childhood, and indeed, I can remember mine replete with all its toys – a fair few of which were inevitably broken. In Rilke’s phrase above, we have an implied progression from childhood to adulthood and the fate that comes to all of us, but travelling back, we move away from death and think of our childhoods, remembering those toys which in our mind’s eye are always new, or at least, always mended. This sense of moving back and the idea of toys, or things, that are mended again, resonates for me with my research and my using the Ancestry website. One can think of the 800 million names stored in their databases as each being a broken toy, one that when it’s found again is slowly put back together.

Having discovered hundreds of names (or broken toys) in my own family tree, I’ve started to put the pieces back together, looking beyond the names to discover who these people were, and therefore, who I really am. And the more I discover, the more I find myself looking at history in an altogether different way. History is sometimes seen as being nothing but a list of dates, but like the names on Ancestry, there are of course a myriad number of things behind the letters and the numbers (the broken toy in the attic has been to places other than just the attic – and has been things other than just a toy).

Now when I think of an historical date, I relate that to my family tree and consider who was alive at the time. For example, when reading about the Great Exhibition of 1851, I know that at that time Richard Hedges, Ann Jordan, Elijah Noon, Charlotte White, William Lafford, Elizabeth Timbrill, John Stevens, Charles Shackleford, Mary Ann Jones among many others were all alive; what is for me a distant event described in books and early black and white photographs, was for them a lived moment whether or not they visited the exhibition itself.

When this photograph inside the exhibition hall was taken in 1851, they were a part of the moment, even when farming in Norfolk. When the guillotine fell upon Marie Antoinette on October 16th 1791 (I’ve just been reading about the French Revolution), Thomas Sarjeant, Ann Warfare Hope, David Barnes, Mary Burgess and William Deadman were going about their normal lives somewhere across the channel in England, and it’s by understanding their lives – of which I am of course a consequence and therefore a part, that I can begin to understand history as not some set, concrete thing that has happened, but something fluid, made of millions of moments which were at one time happening. Every second in history comprises these millions of moments when the world is seen at once by millions of pairs of eyes.

Therefore, as well as being a huge database of names, Ancestry can be seen as being a database of moments, the more of which we discover for ourselves, the greater our understanding of history becomes. This, in light of the project’s origins at Auschwitz-Birkenau, is particularly pertinent; the Holocaust, as a defined historical event, becomes millions of moments and the Holocaust itself not one single tragedy, but a single tragedy repeated six million times.

In effect, Ancestry allows users to map themselves onto history and the family tree becomes not just a network of relationships between hundreds of people but a kind of physical and geographic biography of the individual. Places we have heard of but never been to, places we have never known before become as much a part of our being as the place in which we were born and in which we live. For example, if there’s a place with which I can most identify physically or geographically, then that place would be Oxford, the town in which I was born, grew up and in which I live. Its streets which I have walked and its buildings which I have seen countless numbers of times, all hold memories – and what are we in the end but these.

Of course there are numerous other places which I have visited and which make me who I am (seaside towns in Dorset where I holidayed as a child for example) but as well as these places are those which, until I began my research, I had either never heard of or never visited: Hafodyrynys, Dorchester, Burton Dassett, Southam, Ampney St. Peter, Minety, Ampney Crucis, Cefn-y-Crib, Kingswood, Usk, Eastleach, Wisbech, Walpole St. Andrew and so on. Furthermore, places I had known and visited were shown to contain memories extending way beyond my own lifetime but of which I am nonetheless a part, or at least, a consequence. I have been to Brighton many times and have many memories of that place, but all the times I have been there, never did I realise how much it and the surrounding area had come to make me who I am.

So, as well as being a vast database of moments, Ancestry can be seen as an equally vast set of blueprints, each for a single individual – not only those who are living, but those who’ve passed away. And just as the dead, through the lives they led, have given life to those of us in the present, so we, living today can give life back to those who have all but been forgotten. Merleau-Ponty, in his ‘Phenomenology of Perception’, wrote:

“I am the absolute source, my existence does not stem from my antecedents, from my physical and social environment; instead it moves out towards them and sustains them.”

Of course our existence does indeed stem from our antecedents (and as we have seen, our physical environment), but what I like about this quote is the idea of our sustaining the existence of our ancestors in return. The natural, linear course of life from birth to death, from one generation to the next, younger generation, is reversed. Generations long since gone depend on us for life, as much as we have depended on them.

In his novel, ‘The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge,’ Rilke wrote the following:

“Is it possible that the whole history of the world has been misunderstood? Is it possible that the past is false, because one has always spoken of its masses just as though one were telling of a coming together of many human beings, instead of speaking of the individual around whom they stood because he was a stranger and was dying?”

This quote brings me back round to what I spoke of earlier; the idea that the past is made up of countless millions of moments – that History is not the concrete thing that has happened, but something more fluid, something which was once happening, and which, given Merleau-Ponty’s assertion above, is still happening, or at least being sustained. These moments are the world as seen by individuals. In Rilke’s quote, the history of the world, represented by the masses, has its back turned against us. We cannot see its face or faces, only the clothes that it wears. But the stranger in the middle, around whom history crowds is looking out towards us, and if we meet their gaze, we make a connection, we see the individual. And for a moment they might be a stranger, but through the dialogue which inevitably begins, we get to know them and the world to which they, and indeed, we, belong.

As I’ve said, Ancestry is more than a network of discovered (and undiscovered) relationships between hundreds of people; it’s also an immense collection of dialogues; one can imagine the lines which connect individuals as being like telephone wires carrying conversations between the past and the present. And the more one thinks of all these nodes and connections, the more one begins to see that Ancestry is also a metaphor for memory – after all, what are memories but maps in the brain, patterns of connections between millions of neurons which make a picture of what once was: history as it really is.

Mine the Mountain will run between 1st and 8th October 2008 in Oxford. Download a PDF for venues.

John Stevens (1837-1888)

In my previous post ‘Real People‘ I wrote a little on the life of John Stevens, my great-great-great-uncle (my great-great-grandfather, Jabez’s older brother) who was born in Reading in 1837. Firstly, I must correct something I wrote in that entry; John Stevens was never in Broadmoor . Before entering the Moulsford Asylum, he was first an inmate at the Littlemore Asylum in Oxfordshire to which he was admitted on 24th March 1871. He was suffering from mania caused by epilepsy and had been ill for three months.

He was 34 years of age when admitted to the Moulsford Asylum on 17th May 1871. He was a tailor, married to Emma and had been subject to fits from the age of 17. This was not his first attack of insanity the cause of which was epilepsy. He told the doctor on admission that “he has been all around the world this morning; that he was seen John the Baptist; that he is John the Baptist; that he in a fighting attitude is addressing God.” He had been observed “standing for an hour in one attitude looking at the sky, squaring his fist to fight the Nurse and ill-treating his wife a few days after her confinement.” In the same year he was admitted, his wife Emma gave birth to a daughter, Kate.

As a patient, he still worked in his trade as a tailor as the asylum had its own tailoring shop. However he was still subject to frequent and severe epileptic fits.

On July 28th 1877 he was attacked by another patient, Harry Mulford, who knocked him down and kicked him breaking one of his ribs. Two years later in 1879 he stopped working as his condition began deteriorating.

In December 1886 he suffered with pneumonia and in March 1887 records state that John “is a wretched epileptic, frequently getting wounds in the head.” A year later in December 1887, he was so weak he was spending the entire day in bed, still suffering frequent fits. The next and last entry in the records of Moulsford Asylum regarding John is dated 10th February 1888. It states that he had:

“…been constantly in bed, at times noisy but thoroughly exhausted. He quietly passed away today at 2.30pm.” His cause of death was “exhaustion from epilepsy.”

X

It was whilst I was cycling home from the studio this morning that the idea first came to me. I was thinking about the two paintings on which I am currently working, both of which are based on the landscape around Hafodyrynys, Wales (the village in which my Grandmother grew up) and one of which I intend to show, veiled, at the Mine the Mountain exhibition in October.

The paintings themselves were going quite well, but remembering the original idea behind them, I realised that there was something missing. The original idea was that these paintings, or rather the final selected painting would be based on both the death of my great-great-uncle, Jonah Rogers who was killed in action in the Second Battle of Ypres on May 8th 1915 and my birthday, May 8th 1971. The title of the piece was provisionally May 8th, but as is often the case, the painting has led me away from this. That isn’t to say the subject has been lost completely; I still want to think about Jonah, but how do I show him in the painting? How do I show the ambiguity between existence and nonexistence/death?

The answer came as I thought about names and some of the documents I have obtained through researching my family tree. Almost without exception, none of my ancestors from Wales at this time could read or write and all of them signed their name (or rather, indicated their presence) with an ‘x’. The ‘x’ therefore becomes a sign of a presence, but one which is anonymous.

Of course the ‘x’ is usually accompanied by the line; ‘the mark of…’ (as above) but without that, the human becomes relegated to this nondescript, anonymous sign (one could argue of course that we are all, in our names, reduced to signs, but the ability to write allows us to transfer to the page – and therefore leave to posterity – much more than just the name by which we are known). The act of making that mark instead of writing one’s name is also very significant. It levels all those who make it; it renders everyone the same – at least in the eyes of history. One could say that the greatest leveller of all is death and that the ‘x’ becomes the mark of death; presence is defined by absence.

We know much of what happened in the past through the written word although there are of course many other sources in which it’s also revealed; paintings, artworks, newspaper stories, oral histories/stories, fingerprints, photographs and so on, but for the most part, we know about the past through what we read. I have written about the limits of the written word before in relation to the work I did on ‘The Gate’, but looking at it again in relation to these paintings and to my previous work/research, there is something very poignant about these anonymous signatures; I can’t help but think of the names we see on memorials, carved into walls and so on. Imagine if they simply read ‘x’… For many who died in the Great War and whose bodies were either never found, names have been lost and an ‘x’ is perhaps all one could write on their behalf.

In relation to the landscape, ‘x’ has different connotations; on maps it marks a spot – it denotes the presence of something, a thing which is present and yet absent – hidden away from sight and mind like buried treasure. Marking the canvas with an ‘x’ would give the painting the meaning I was looking for; the presence of someone absent; the reduction of everyone in time to complete obscurity. Furthermore, taking what I wrote in the paragraph above, ‘x’ marks the last resting place of all those (including my great-great-uncle) whose bodies were never found.

The paintings are still in the early stages but there was instantly something about the marks which appealed. In some respects I saw them (those in the sky) as angels which given the nature of the work seemed relevant. They also reminded me of the stars one sometimes finds painted on the ceilings of cathedrals or in mediaeval manuscripts. But those ‘on the ground’ called to mind something else, something which given Jonah Rogers’ fate gave the paintings another dimension; first the shape reminded me of the deckchairs I made for the Residue exhibition (The Smell of an English Summer 1916 (Fresh Cut Grass))..

…and secondly, the x-shape defences one sees on wartime photographs such as those of the Normandy landings below…

Real People

For about seven months now I have been researching my family tree through Ancestry.com and in that time I have been quite successful, tracing four lines (Hedges, Stevens, Jones and Sarjeant) back to the beginning of the nineteenth century and in some cases well beyond. I have exchanged emails with a second cousin in Canada (to whom I owe a great deal as regards his efforts with the Sarjeant tree), visited the graves of ancestors I never knew I had in Wales and, having visited the Menin Gate in Ypres a year ago, discovered that my great-great-uncle is commemorated upon it having been killed in the second battle of Ypres in 1915 (there may be a second great-great-uncle who died at the Somme, but until I receive his death certificate I cannot be certain). Having done all this and talked with both my 95 year old grandmothers about their respective childhoods, and having looked at various photographs, these people I have drawn from the past have come alive, but it was only at the end of last week, that the fact these were once real people became truly apparent.

The furthest I’ve gone back with the Stevens family is to a certain John Stevens, a tailor, who was born in Oxford around 1812. The Stevens side of the family (my maternal grandfather) came to Oxford in 1952 from Reading, so it was strange therefore to find that they’d originated in the twon where I was born. He had six children by his wife Charlotte; John (1837), Samuel (1839), Elizabeth (1843), Rosetta (1844), Henry (1846) and finally, my great-great-grandfather, Jabez (1848). Having turned my attention recently to those to whom I am not directly descended, i.e. the siblings of great-grandparents and so on, I decided to look at the eldest sibling in this family, John.

Born in 1837, I traced him through the censuses and discovered that in 1857 he married Emma Fisher and with her had seven children; Emma (1859), William (1861), Henry (1863), Mary (1865), John (1867), Martha (1869) and Kate (1871). All of these I found listed on the 1871 census along with their mother, but, there was no mention of the father John. I looked ahead to 1881 and while I couldn’t find Emma, I found her children and her husband, and it was here in this document that the whole tree assumed a much more tangible dimension. In 1881 John was listed as a Pauper Patient in the Berkshire County Moulsford Asylum (now Fair Mile Hospital). Why he was in there I couldn’t say, but next to his name was his trade ‘Tailor’ (the same as his father) and the word ‘lunatic’.

Suddenly, this man seemed more real than any of those I’d previously discovered; so for that matter did his wife and their children, after all, if he was in an asylum, what had become of them? I couldn’t find any mention of Emma, but some of his children had been separated; Henry and John were living with their Uncle Samuel, also a Tailor; Mary was living with her Aunt Rosetta, and sadly, Martha and Kate, the two youngest sisters, were inmates at the Reading and Wokingham District School (workhouse).

Turning back to the fate of their father, John, I tried to find him in the 1871 census, and eventually I discovered him; it seemed his misfortune had come much earlier for he was at this time an inmate at ‘Broadmoor Asylum for the criminally insane.’ I’ve no idea yet what he did but clearly it was serious. Reading about the asylum I read that those found ‘not guilty’ of serious crimes through their insanity were at the end of their sentences assessed, and if found to be unfit for release were sent to county asylums which seems to have been the case with John.

As regards his wife Emma, I have yet to find any trace of her in the 1881 census. It might be of course that she died in the 1870s but a search for the record of her death yields a more likely date of 1885; this will of course require more research. As regards John, I found reference to a John Stevens, born in 1837 who died in the district of Wallingford (in which Cholsey – the location of the Moulsford Asylum would fall) in 1885. No doubt he never recovered his sanity or his freedom.

As to the fate of their children, that will of course need further research.

Henry Jones’ First Wife

I have been looking to find the first wife of Henry Jones for a while now having got it wrong first time round, albeit getting her first name right. I had – for reasons I cannot recall – listed her as being Mary Carey, but have since discounted that having found no matching record for their marriage.

In May, we visited the graveyard in Cefn-y-Crib which some of my Welsh ancestors are buried, and there found the grave of Henry Jones, which we could see was also the grave of his second wife Rachel and his first wife Mary and daughter Lydia.

The gravestone was a little damaged and the name of his first wife a little bit obscured, but one could nevertheless make out the name, Mari – the Welsh spelling of Mary. But what was her surname?

Having searched through the marriage indexes I came across a few possibilities that fitted in with the dates they would have been wed; Mary Lewis (1859), Mary Harris (1860) and Mary Issacs (1860). The last of these names rang a bell, and when I looked at the certificate for Henry’s marriage to his second wife Rachel, I saw the name Anne Isaac as being one of the witnesses.

Edmund Jones, the other witness, was the father of Rachel Jones (Jones was also her maiden name) and so I can only assume that both Henry’s parents were dead at the time. Of course, Isaac is not Isaacs but then spelling mistakes were made. Furthermore, when searching for Mary Issacs’ birth, I found only a few, all of whom would have been too young to have married Henry in 1860. Could the name have been wrong on the marriage index? Should it have been Isaac?

We know that she died in 1869 at the age of 27 and having searched for Mary Isaac in the birth records I found one Mary Isaac, born in the Pontypool district in 1843. But what of the other contenders; Mary Lewis and Mary Harris? There were a number of Mary Lewises born in 1842 (which one assumes is the correct year of birth), as indeed there were a number of Mary Harrises also born in 1842.

8th May – A Painting

This is the second day of working on the painting which will be shown as part of my ‘Mine the Mountain‘ exhibition. The title, 8th May, alludes to both my date of birth and the date my great-great-uncle, Jonah Rogers, was killed in action at the Battle of Frezenberg Ridge (Second Battle of Ypres) in 1915.

When the painting is shown it will be veiled to represent the death of my ancestor. When the veil is lifted, the work will of course be changed to represent my own coming into being. Veiled, the scene is obfuscated, hidden from the deceased to prevent his getting lost on his way to the next life; when lifted, the scene is presented as I remember it, or know it.

Rogers Conundrum II

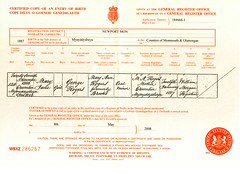

Following on from my previous post on this subject (see Rogers Conundrum) I obtained today a copy of my great-grandmother’s birth certificate.

On the certificate, it clearly states that Mary Jane Rogers was born on 27th November, 1886 in Crumlin, Mynyddyslwyn; that her father was George Rogers and her motherMary Ann, formerly Brooks. Having Mary Ann’s maiden name is obviously a great help, but it just goes to show that censuses can be wrong.

Below is a detail of that census.

In this entry there are two errors; one the name of George’s spouse which should read Mary A and not Sarah A, and secondly the name of their daughter (my great-grandmother) Mary Jane which is given as Bessie J.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- …

- 31

- Next Page »