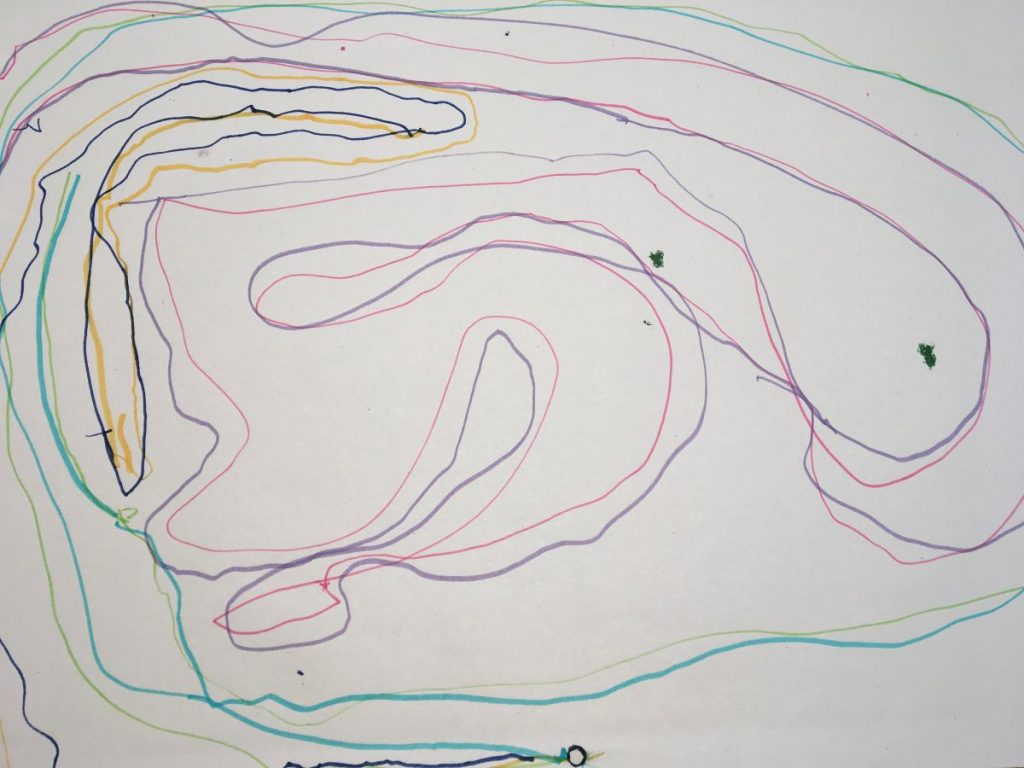

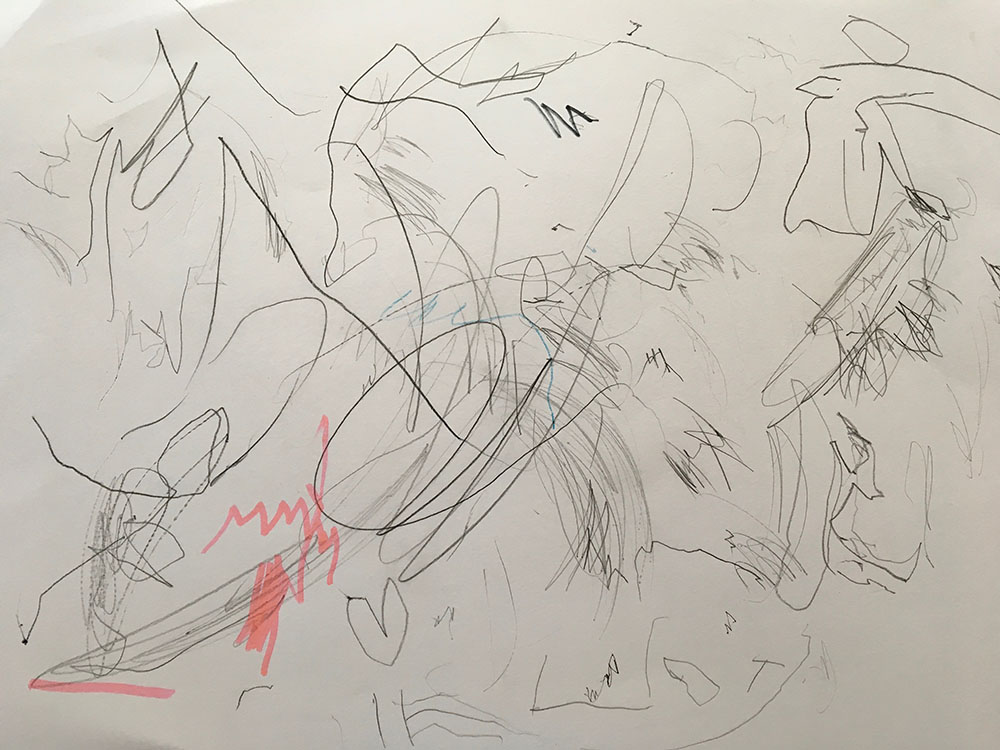

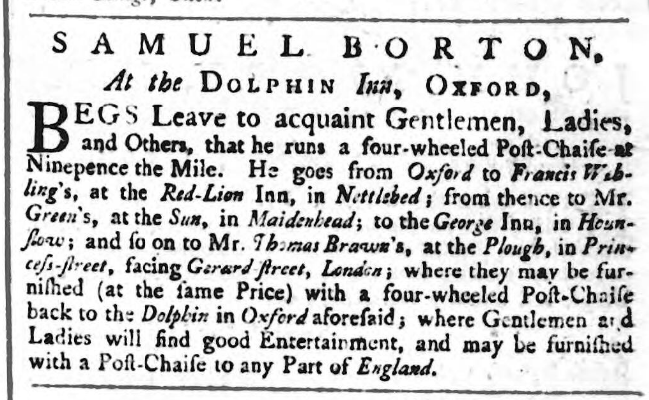

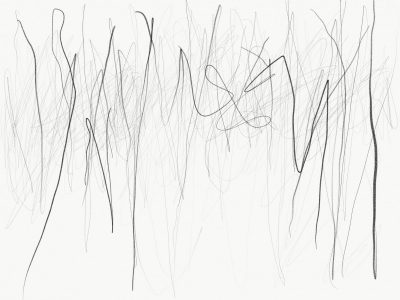

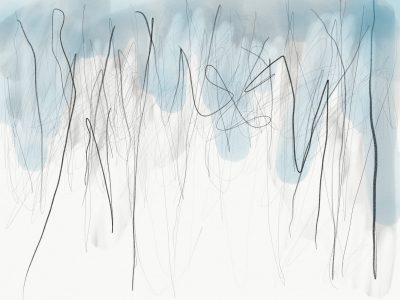

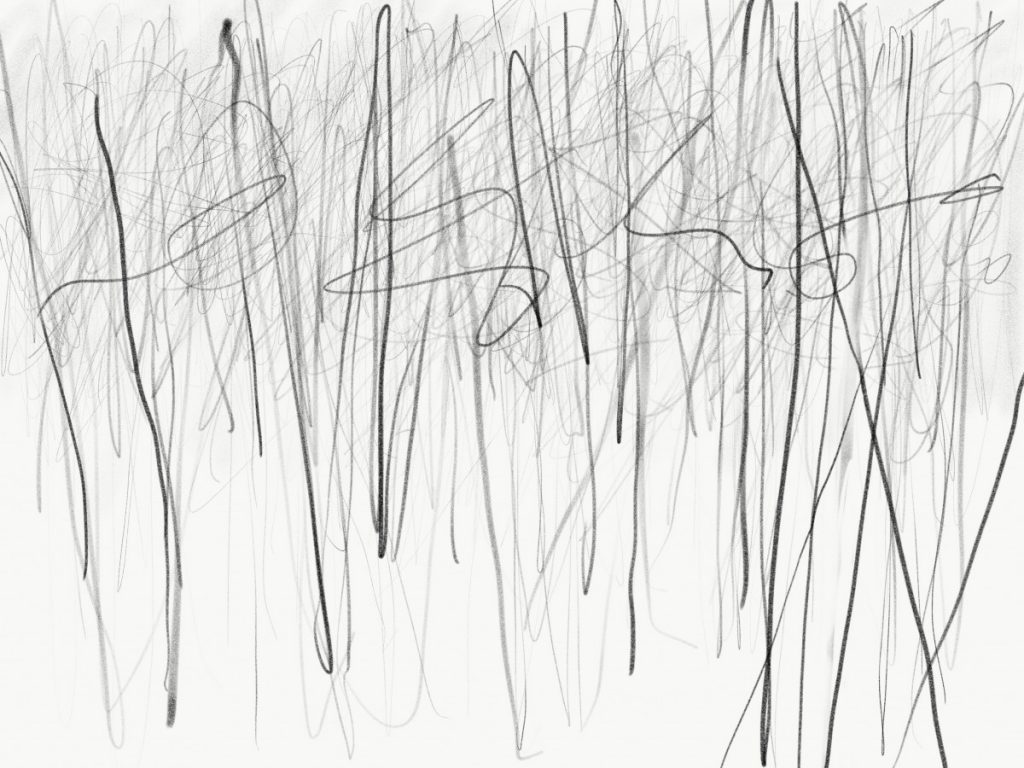

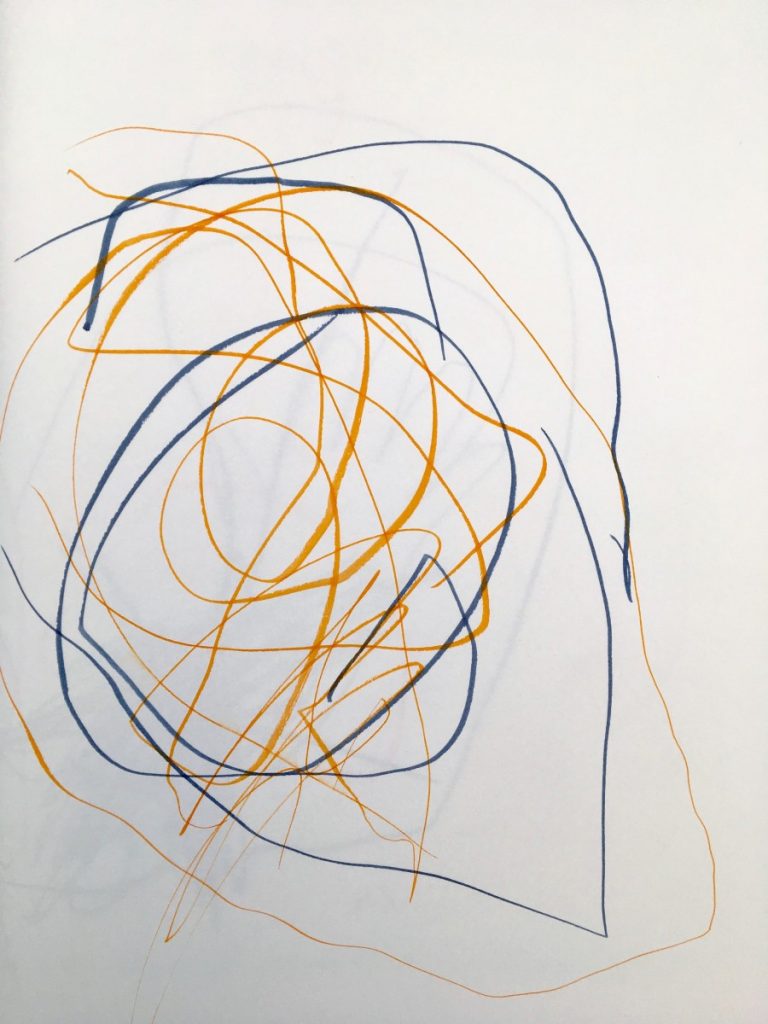

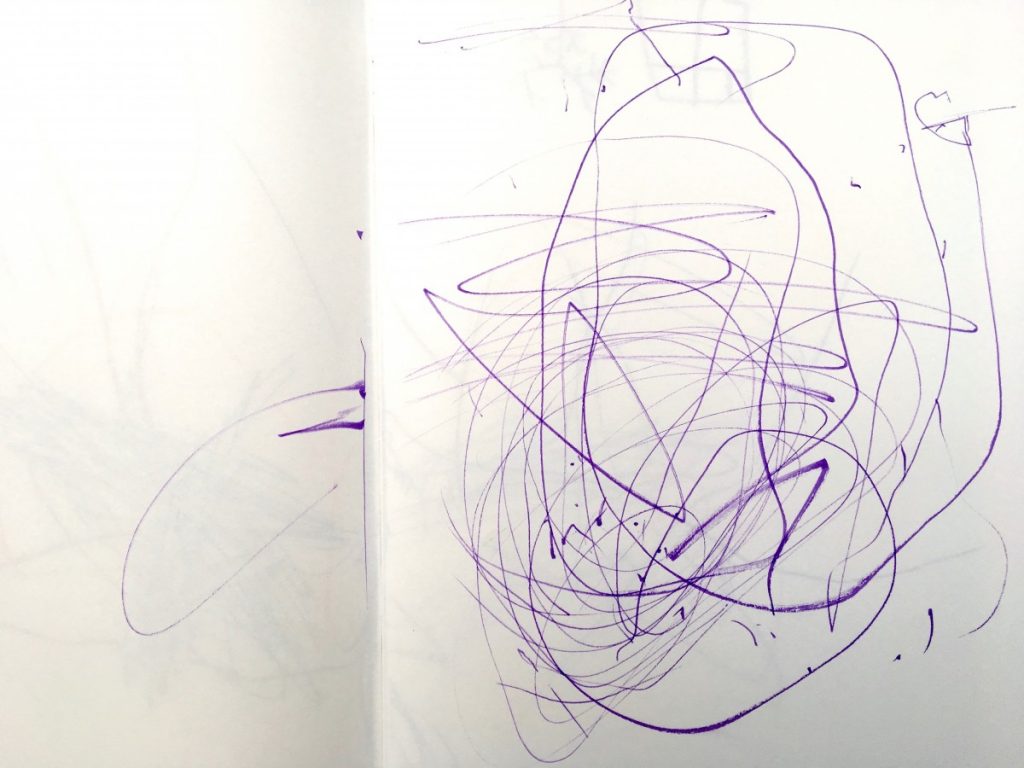

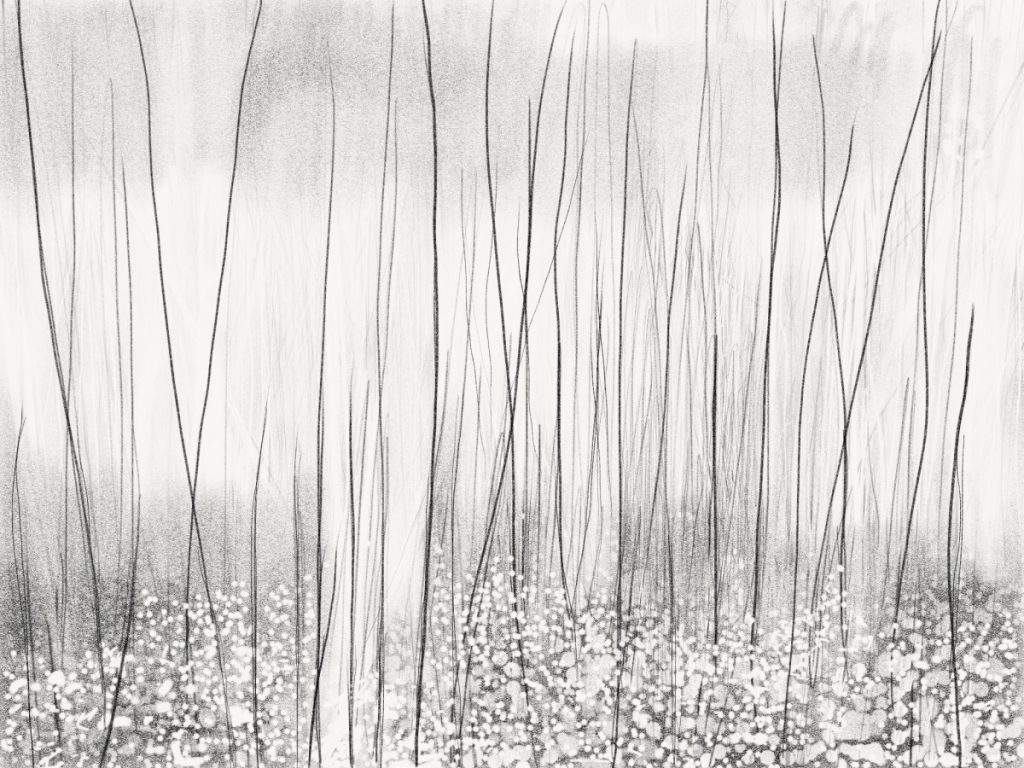

Much of my work of the last ten years or so has been to do with the past, with imagining a moment in the past in all its lost ‘presentness’. The work I’ve been making recently with my 3 year old son’s drawings (‘Missded’) has thrown up what could be an interesting metaphor in that regard.

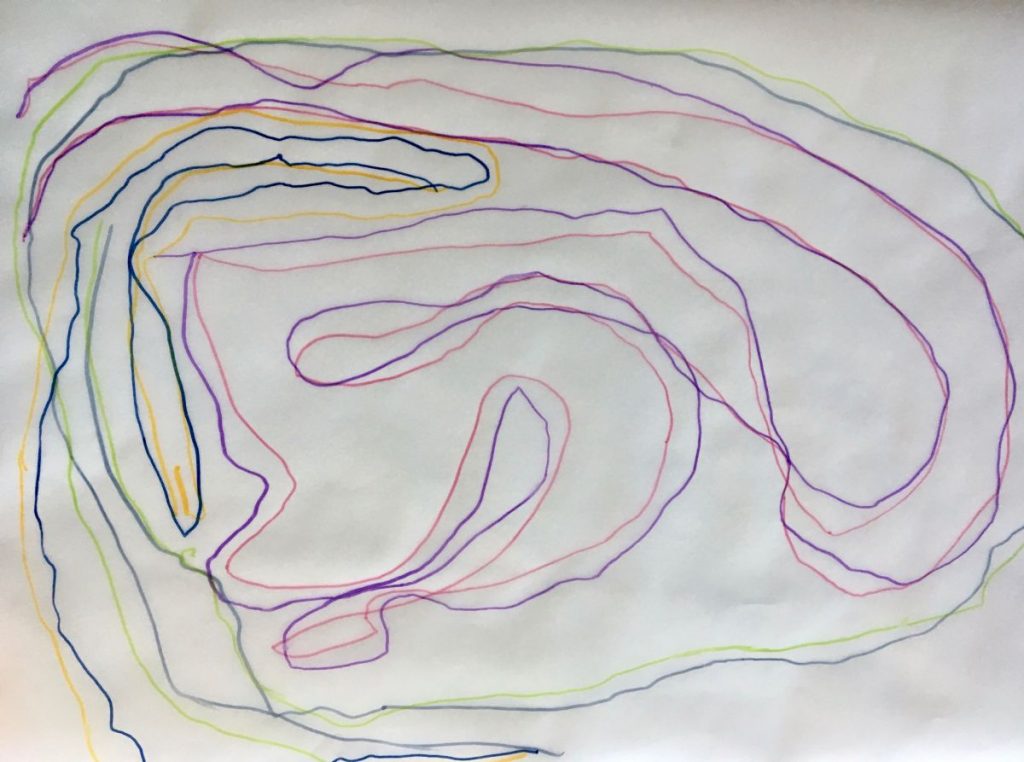

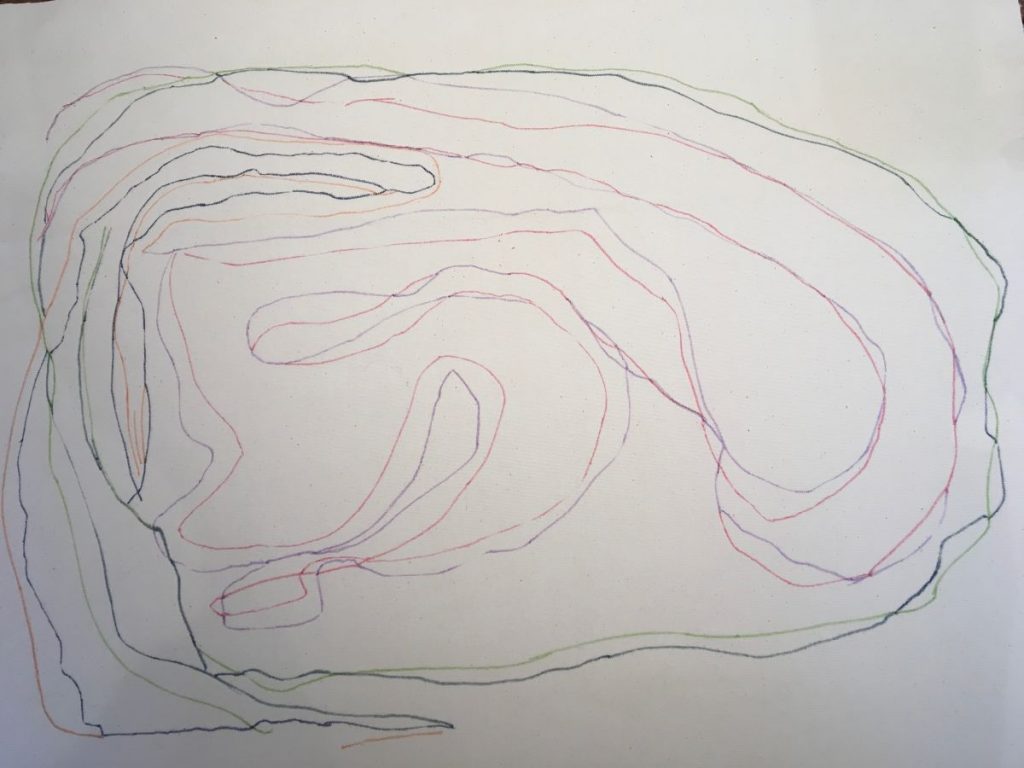

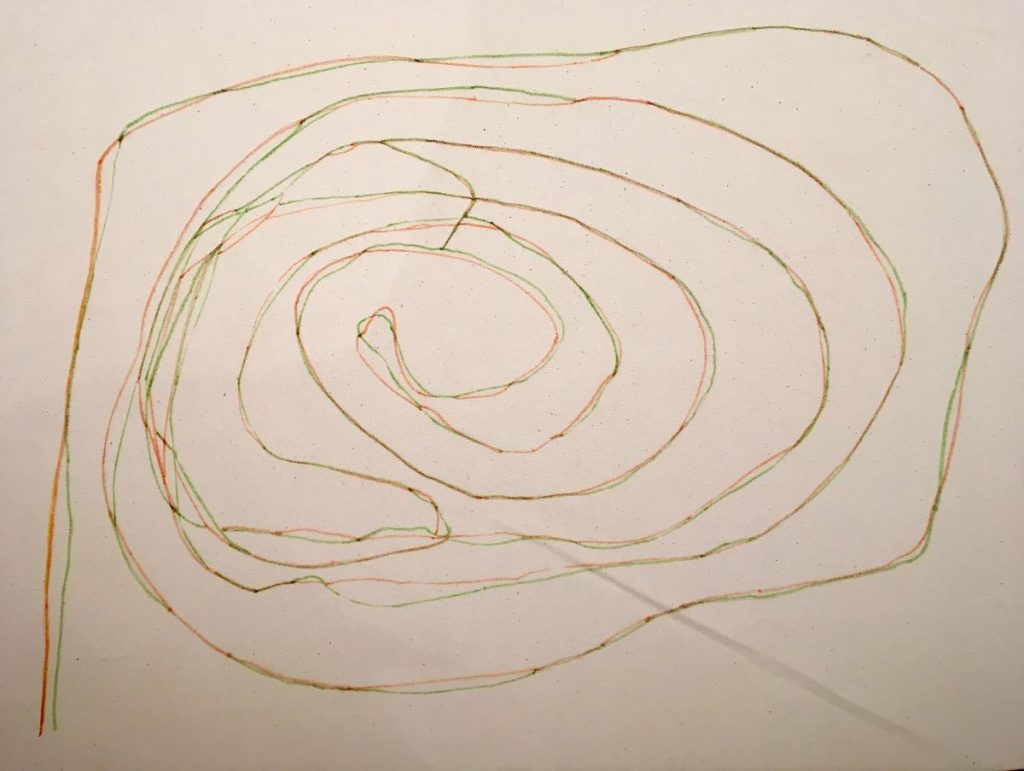

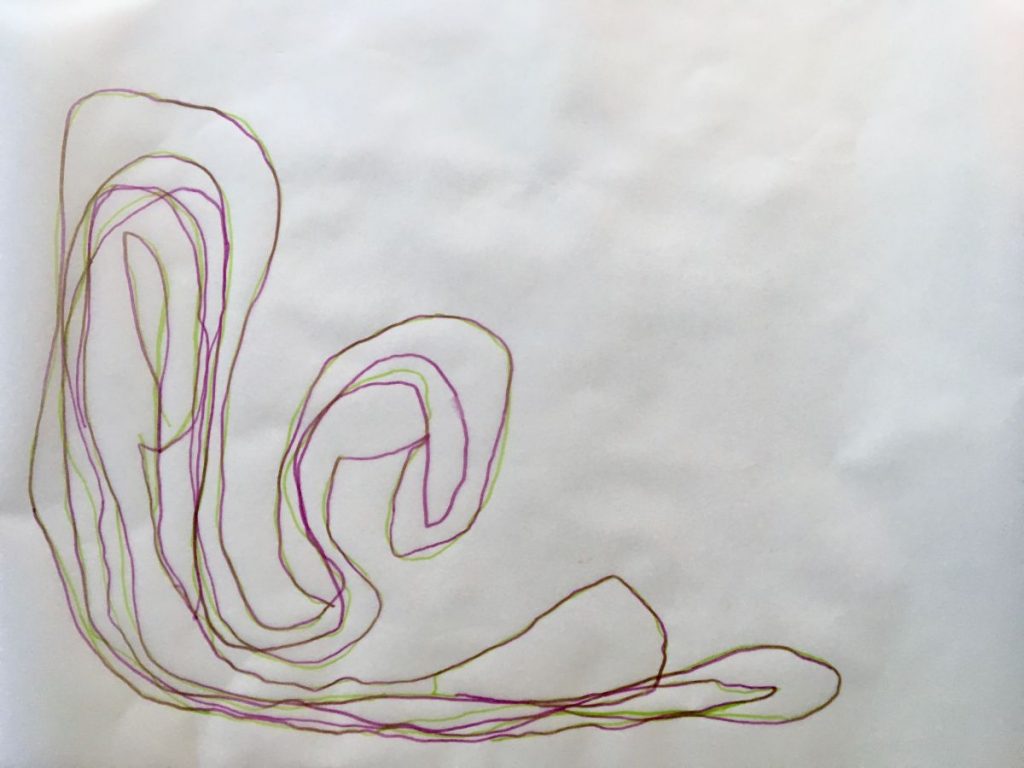

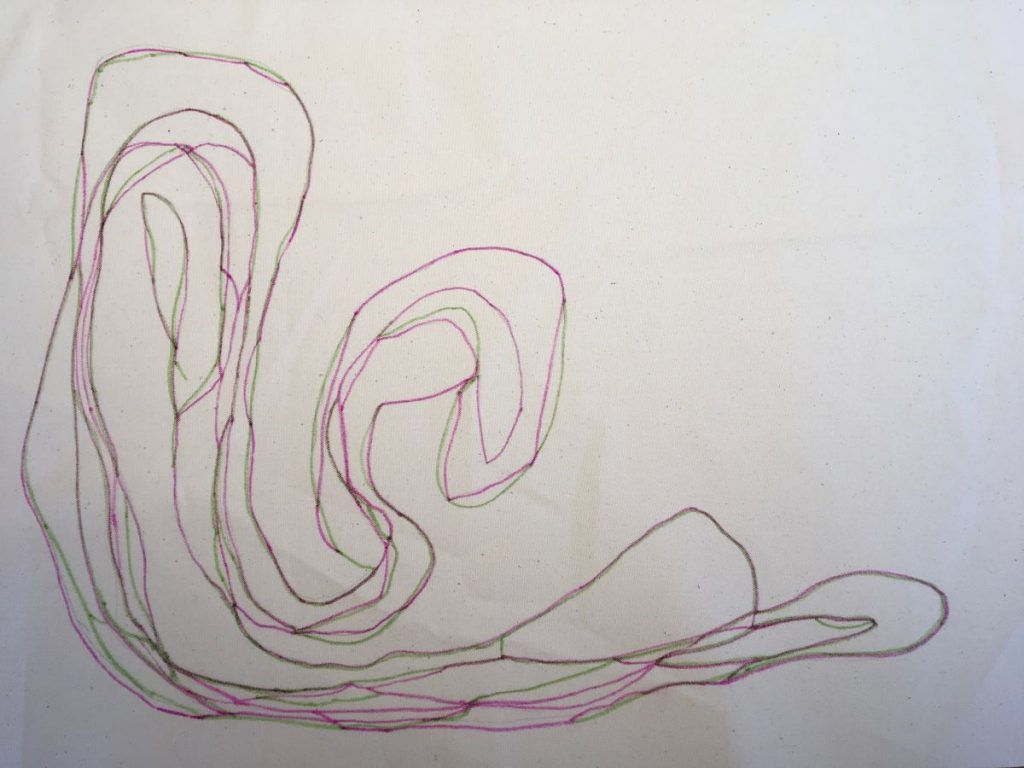

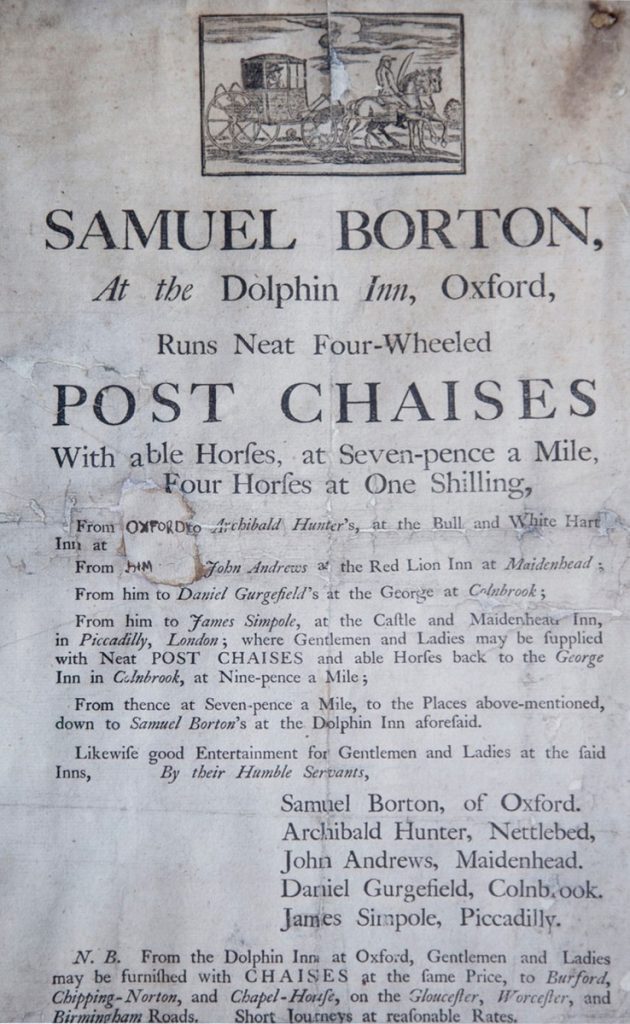

As I’ve written recently, where my son’s original drawings were ‘about’ lines, the transferring of those drawings to canvas is a process more concerned with spaces. In other words, the lines on the canvas, which echo the original pattern of the drawings, are lines drawn around spaces rather than a single line drawn through a space as in my son’s original drawing. It’s this contrast which interests me.

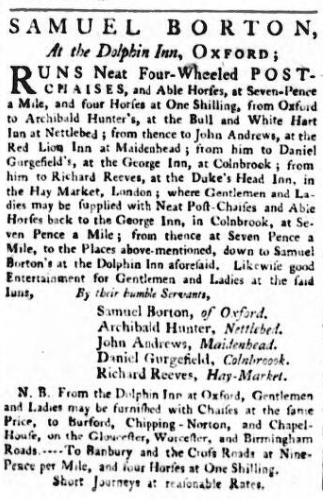

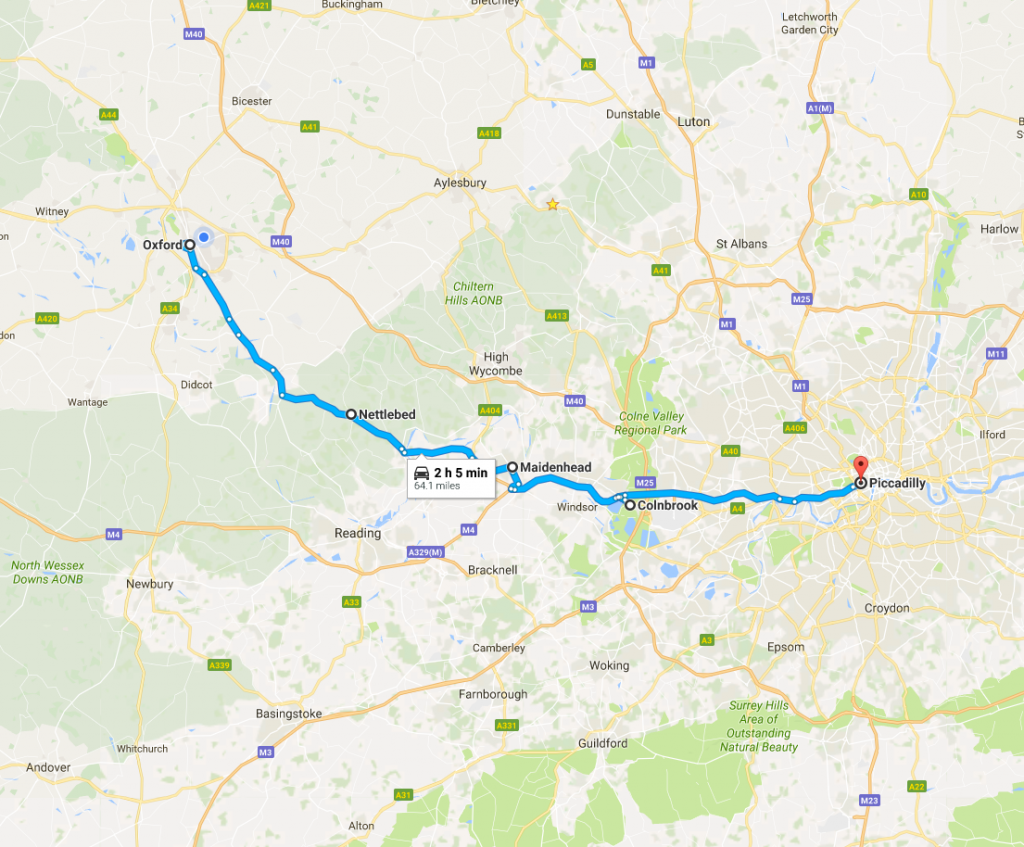

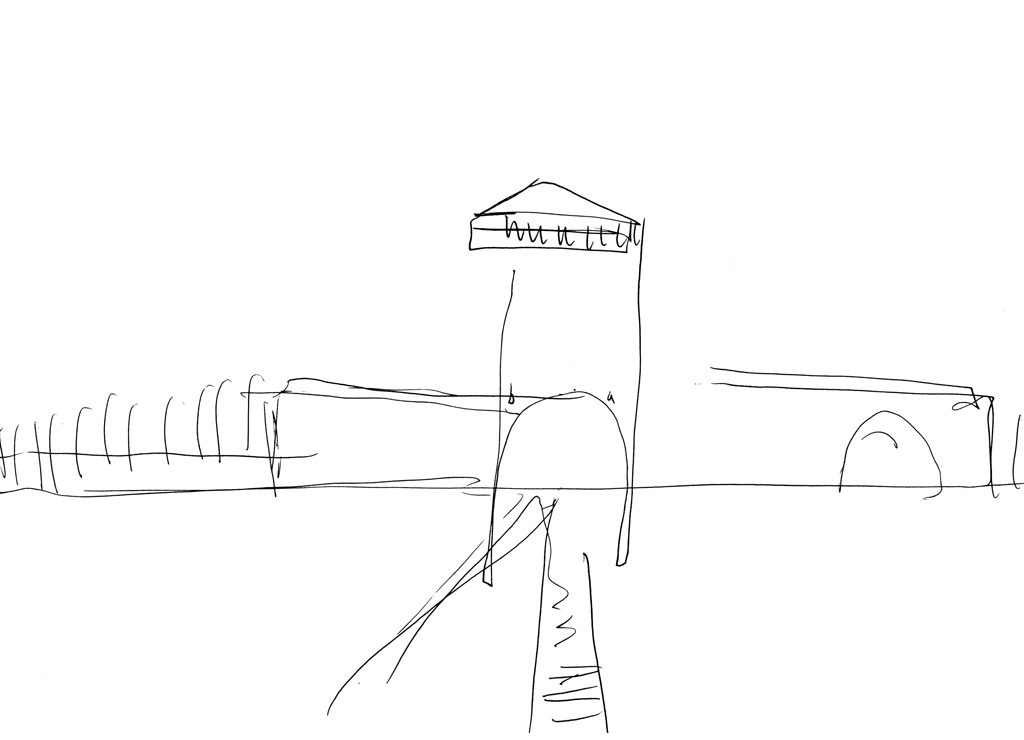

It reminds me of some work I did quite a few years ago when I walked a route around town, capturing what I could see in lists of words. When I looked at the route ‘drawn’ on my GPS unit I was interested in the spaces between the lines of my walk and all that had happened in those spaces – all the things which were part of the same moments captured on my lists, but which I hadn’t witnessed.

The past moment, in all its ‘presentness’, is like that line drawn in a matter of seconds across the paper, and history, the recreation of that line through the delineation of many empty spaces.

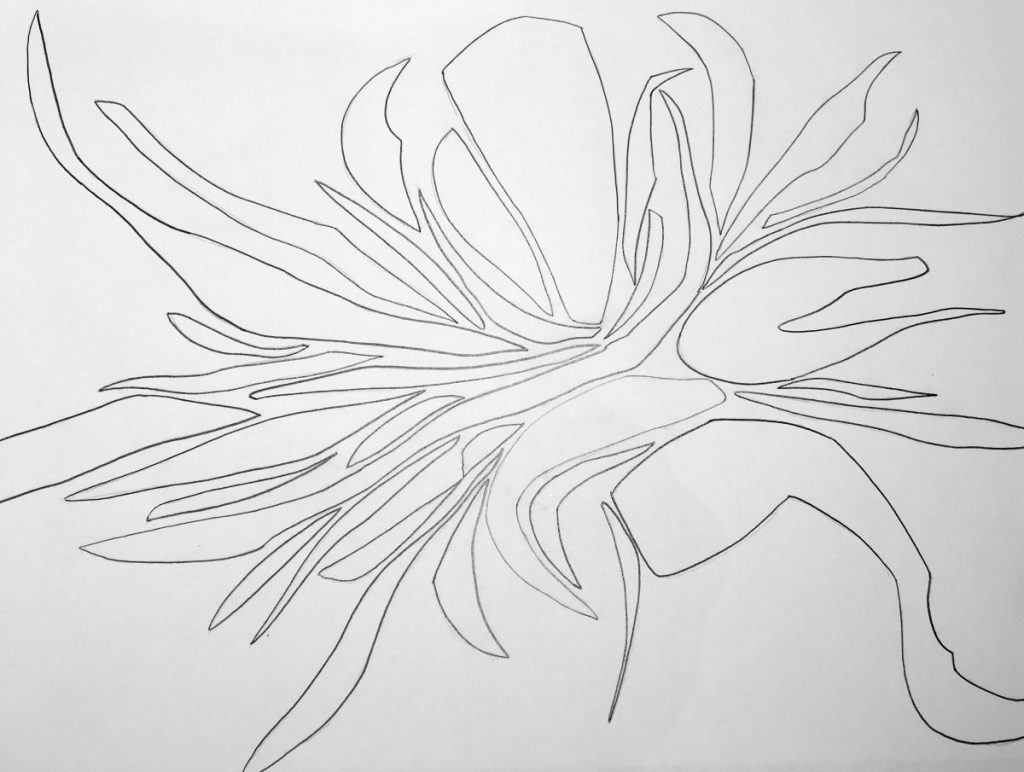

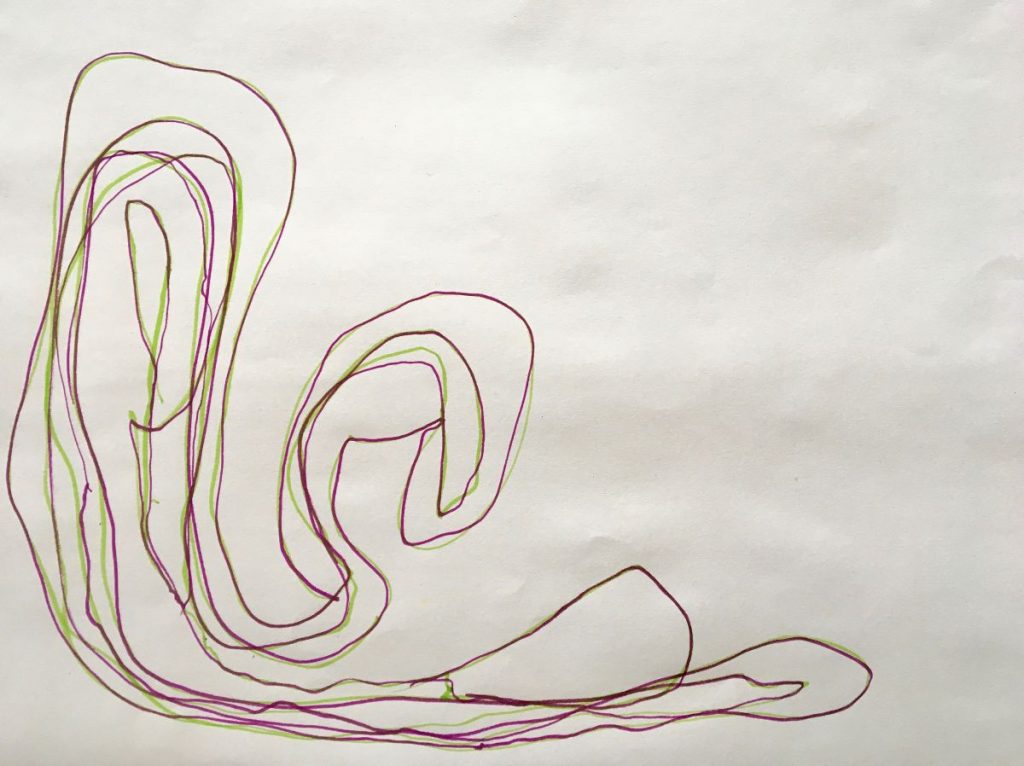

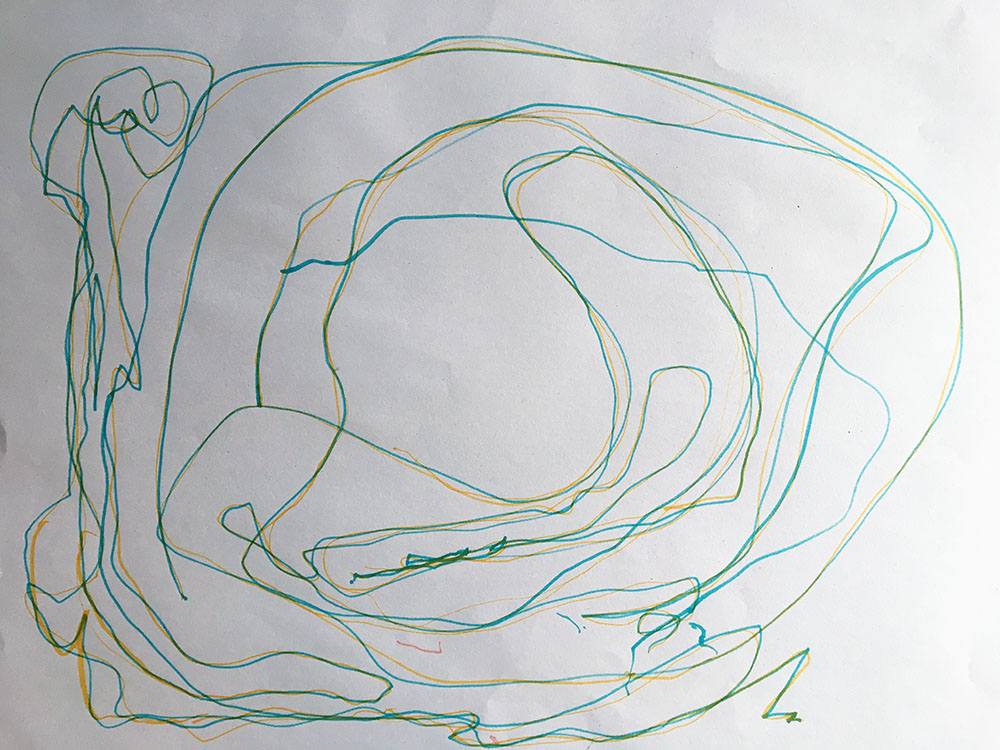

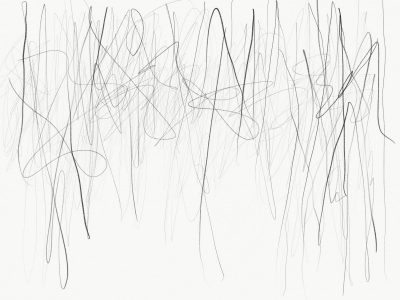

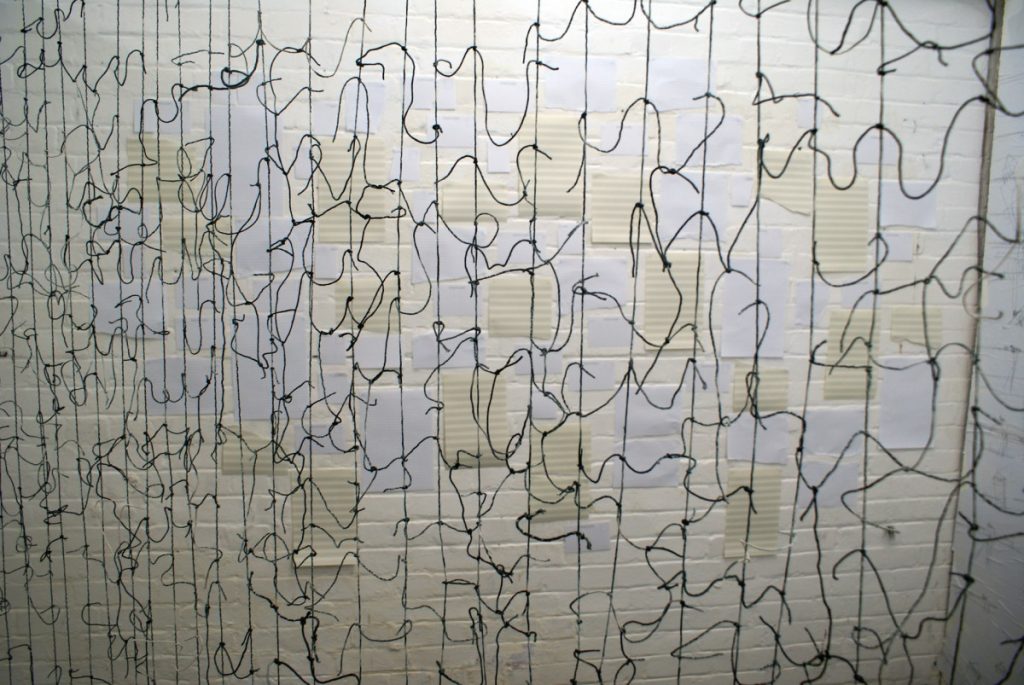

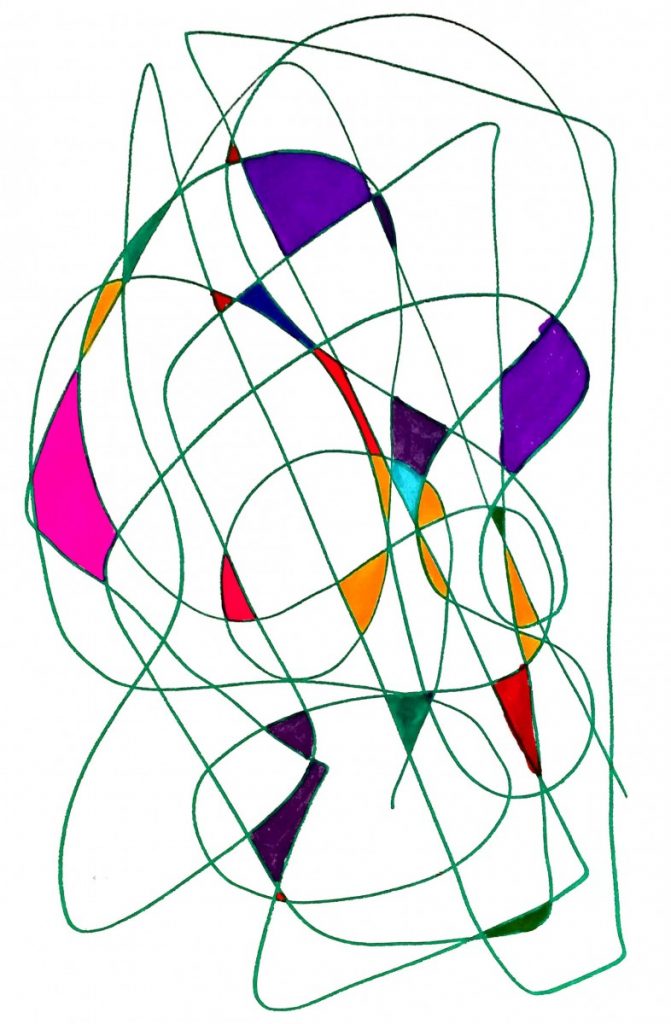

With a pile of cut out spaces left after the job of transferring the image to canvas, I started another piece which used those fragments, arranging them on the fly to create a pattern.

I’ve no idea yes what this will lead to, but I like the organic feel of the piece. I’m imagining that it will become a more intricate, finished work, and again, this will provide an interesting contrast between the piece made by my son (an intricate pattern made in seconds) and that made by me (an intricate pattern, derived from the drawings, but made over many hours).