On what was a beautiful Autumn day, I took a walk to Shotover wood to take some photos of trees. I’ve always loved Shotover, both for its place in my past and that of my family, and its own history, being as it once was the main road to London (the mounting steps at the top and bottom of the hill are particularly interesting). The following images are a few of the photographs I took.

Trees and Other Projects

I have been photographing the same trees – shown above – for almost 18 months now, and what started as a simple photographic record of a particular set of trees has since morphed into a project which shares certain aspects with other lines of research. I was drawn to them initially by their shape and proportions; by the fact that they reminded me of an Isaac Levitan painting, such as that below.

Since then, as my personal circumstances have changed through separation, the trees have come to signify something else. Being separated from my children for much of the week, there’s a connection between this anxiety and that which is present in the postcards of World War I servicemen, photographed in studios before they left for the Front, often against a painted backdrop of trees.

I worked on this theme previously, working with postcards such as that above and creating montages that used photographs I’d taken of trees at one-time battlefields such as the Somme and Verdun.

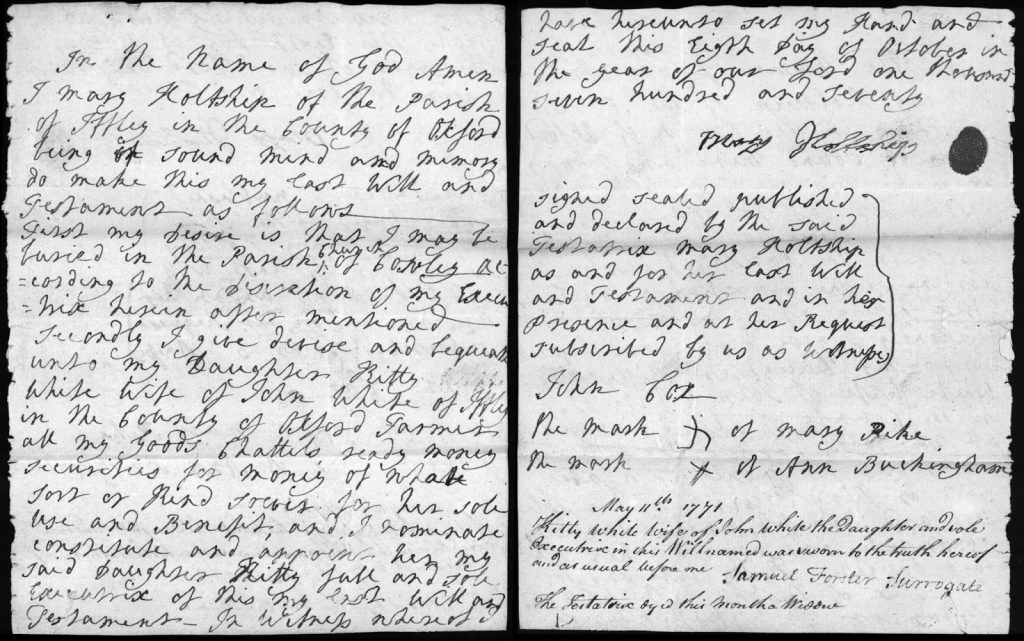

Mary Holdship

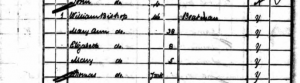

From reading William Holdship’s Will (1757), we can glean that he had 4 children:

John

Thomas

Mary (married to Thomas King)

Kitty

In Mary’s will, written in 1770, we read that everything was left solely to her daughter Kitty, wife of a farmer in Iffley called John White.

One wonders why everything was left to her, indeed there is no mention at all of John, Thomas or Mary. Had there been a family dispute? We know that Thomas was living abroad at the time William wrote his will in 1757, so it’s possible that he remained so. The other possibility of course is that all the other children were dead by the time Mary wrote her will.

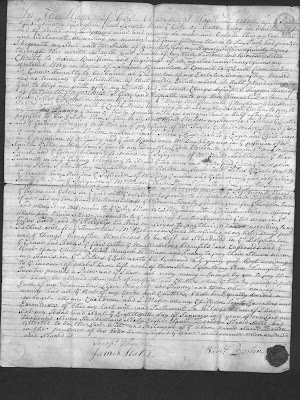

What is particularly interesting about the Mary’s original will is the fact it appears to be written in her own hand.

It’s very strange to see the hand of one of your distant ancestors, a woman (my 7x great-aunt) born in 1697. It’s been written many times how our existences are so incredibly unlikely, and looking at documents such as these, where one can see the passage of a short moment of time through the flow of someone’s writing, one’s very existence seems to hang, literally, on every word.

William Holdship

In Samuel Borton’s will we read:

and Mr Holdship his heirs or assigns to pay their share according to my father’s will for the house that Mr Robinson lives in which was my sister Mary’s past

I found the will (1757) of a William Holdship, farrier …

…in which I read the following:

I give devise and bequeath unto my son John Holdship all that tenement situate on Magdalen Parish in the said City of Oxford now in the occupation of William Robertson to hold unto my said son John Holdship from and immediately after the decease of my loving wife Mary Holdship…

Could William Robertson be the Mr Robinson in Samuel’s will?

In Richard’s will of 1714 we read:

I give my Daughter Mary the House next Mr Phipps house

This doesn’t give us a parish but I can’t help but think that Mary Borton must have married William Holdship.

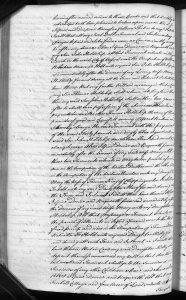

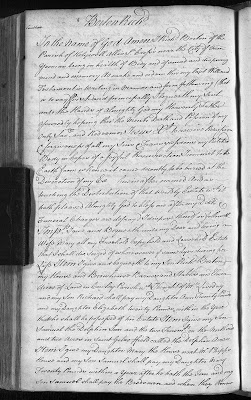

Samuel Borton’s Last Will and Testament 1769

In the name of God Amen I Samuel Borton of the Parish of Saint Mary Magdalen Innkeeper near the city of Oxford being in health of body and of sound and disposing mind and memory do make and ordain this my last Will and Testament in writing in manner and form following that is to say first and principally I bequeath my soul unto the hands of Almighty God my Heavenly Father assuredly hoping through the merits of Death and Passion of my only Saviour and Redeemer Jesus Christ to receive remission and forgiveness of my sins and transgressions My wretched body in hopes of a joyfull[sic] resurrection I commit to the Earth from when it came decently to be buried at the discretion of any Executrix herein after named and as touching the distribution of that worldly estate which it hath pleased almighty God to bless me with after my debts and funeral charges defrayed I dispose thereof as followeth Imprimis I give and bequeath unto my son Samuel Borton my house called the Dolphin Inn in the parish of St. Mary Magdalen with the Brewhouse wash house Stables yards and gardens with the Coach house belonging to it and my son Samuel Borton to pay to my Daughter Fanney the sum of Thirty pounds within one year and a half after he is possessed of his Estate ITEM I give to my son Richard Borton my house in St. Peter in the East and the garding[sic] belonging to it now in the possession of Mr Taylor Cabinet Maker ITEM I give to my son William Borton my house in St. Peter in the East next to the Eagle and Child now in the possession of Mr. Dry and the two rooms over Mr. Dry’s shop now in the possession of Mt Smith the Shoemaker ITEM I give to my daughter Lydia my house in St. Mary Magdalen Parish and the garding belonging to it now in the possession of Mr Chitto and likewise the next tenement with the garding belonging to it and the two acres in St Giles Fields called the Dolphin Acres ITEM I give to my Daughter Margaret Borton my house in St Peter in the East next to the Angel Inn now in the possession of Mr King the mason and the house and yard and Garding joining to it in the possession of Mr Mace the Taylor ITEM I give to my daughter Fanny my house in St Peter in the East next door to Mr Watson’s now in the possession of Mr Baggs the Taylor and the house in the yard with the out House opposite to it both which Mr Bissell rented of me and my son Samuel Borton shall pay to the Beedsman Twenty pounds a year for the Dolphin Inn and when it is to be renewed to the city (illegible): my daughter Lydia her heirs or assigns shall pay their share answerable to the income of her two houses and the two acres in St. Giles Fields and Mr Holdship his heirs or assigns to pay their share according to my father’s will for the house that Mr Robinson lives in which was my sister Mary’s past and the things hereafter mentioned to be left as Standards in the Dolphin Inn (?) and hooks the fixed grates the mantel shelves (?) cupboards and the rest of my children, Richard Margaret William and Fanny to pay their share when my houses in St. Peter in the East are to be renewed(?) and the yearly quit rent according to the income of what I have left each of them ITEM I give to my three daughters twenty pounds a piece and if I have not ready money enough by me to pay them it shall be allowed them out of any goods and chattels when the twenty pounds is paid each of my Daughters Lydia Margaret and Fanny and then what remains in money all the rest of my goods and chattels shall be equally divided amongst all my children and I make all my children joint executors and executrixes of this my last will and testament In (?) whereof I have set my hand and seal the Eighteenth day of January in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and sixty eight Samuel Borton in the presence of us who have signed the same in his presence when he sealed and signed it Thephs Wharton James Slater

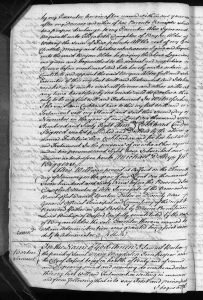

Richard Borton’s Last Will and Testament 1714

Transcript of Richard Borton’s will 1714.

In the name of God Amen I Richd Borton of the Parish of Holywell all is (?) St. Cross’s near the City of Oxon yeoman being in health of body and sound and disproving mind and memory do make and ordain this my last Will and Testament in writing in manner and form following (that is to say) first and principally I bequeath my soul unto the Hands of almighty God my Heavenly father assuredly hoping thro’ the merits Death and Passion of my only Saviour and Redeemer, Jesus Xt to receive remission and forgiveness of all my sins and and transgressions My retched[sic] body in hope of a joyful resurrection I commit to the Earth from whence it came decently to be buried at the direction of my Executors herein after named and as touching the distribution of that worldly estate which it hath pleased Almighty God to bless me after my debts and funeral charges are defray’d (illegible) as followeth ITEM I give and bequeath unto my dear and loving wife Mary all my Freehold, Copyhold and Leasehold Estate that I shall die (seized?) wheresoever ye same (illegible) during her life ITEM I give and bequeath to my son Richd Borton my House and Brewhouse Barnes[sic] and Stables and Eleven acres of land in Cowley Parish I bought of Mr Loveday and my Son Richard shall pay my Daughter Ann twenty pounds and my Daughter Elizabeth twenty pounds within the year that he shall be possessed of his estate ITEM I give my son Samuel the Dolphin Inn and the two tenements on the north side and two acres in Saint Giles field called the Dolphin Acres ITEM I give my Daughter Mary the House next Mr Phipps house and my son Samuel shall pay my Daughter Mary twenty pounds within a year after he hath the Inn and my son Samuel shall pay the Beedsman and when they renew to the city Mary on her heirs or assigns shall pay according to that income ITEM I give to my Daughter Ann my house in St. Clement’s with the forest(?) money belonging to it ITEM I give my Daughter Elizabeth my House and Barn and Smiths shop and Garden over against my Brewhouse ITEM I give my daughter Martha my six acres of land in Headington Field with the Cottages Commons belonging to them and a clove(?) at Cowley now called the Hop Yard on (illegible) and if my son Richard will not surrender the six acres and the house as I have directed ye he shall pay my daughter Ann seven score pounds more than I have directed before and my Daughter Martha fourscore pounds if he doth not (illegible) to her. I leave my Ash house which now stands where the dog kennell[sic] formerly stood to my wife to be disposed of either in the payment of debts or otherwise as she shall think convenient and if it shall please God if any one of my children die before they come to possession of what I leave herein by my will allotted to (them?) then shall they share or (illegible) or Estates belonging or by my will so given and bequeathed to him or her so dying be divided equally to the rest of them that shall be the survivors. And my loving wife shall enjoy all my Estate so bequeathed unto her during the term of her life if she lives a widow but if she marry then each and every one of my children shall enter upon and take possession of what I have herein by my will bequeathed unto them so soon as she shall marry and if my stock that I leave behind me do not prove sufficient to pay and discharge what debts I owe at the time of my Death and my Funeral charges then shall every one of my children bear a proportionable charge according to what I have hereby given to them of the payment and the discharge of the same and so the intent that this may be known to be my last will and testament revoking hereby all former wills whatsoever by me made I have hereunto set my hand and seal this Seventeenth day of December in the year of our Lord One thousand seven hundred and fourteen Richard Borton signed sealed and attested to be the last will and testament of the above named Richd Borton in the presence of us who have signed the same in his presence when he sealed and signed it Mary Gardner, Tom (illegible), Tho. Cave

Wills

Having discovered that my 6 x great-grandfather Samuel Borton owned The Dolphin Inn (which stood on St. Giles, Oxford), I was pleased today to discover his and his father’s wills. Samuel was born in 1706 and died in Oxford in 1769, leaving behind a fair few houses and bits of lands to be divided up amongst his children.

The image below shows his original will:

I was pleased to read the following which confirmed my previous research:

“I bequeath unto my son Samuel Borton my house called ye Dolphin Inn in the parish of St. Mary Magdalen with ye Brewhouse, Washhouse, Stables and Gardings with Coach House belonging to it.”

I was surprised at how many properties he owned in the city including a house in “St. Peters ye East next to ye Eagle and Child”; another house in St. Mary Magdalen which he bequeathed (along with two acres in St. Giles’ fields called Dolphin Acres) to my 5 x great-grandmother Lydia Stevens. He also owned a house next to the Angel Inn on the High Street (pictured below in 1820).

When I examined the will of his father Richard, who died in Oxford in 1714, I found that the same properties were listed in his will and that he had himself owned the Dolphin Inn. The first page of his registered will can found below:

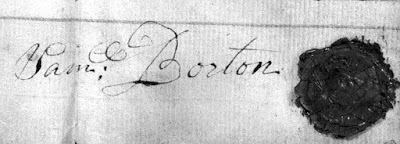

But what I was particularly thrilled to see was an example of Samuel’s handwriting in the form of his signature.

Pastoral Annotations

I’ve been taking a lot of photographs of shadows, particularly that of foliage on pavements. I’m especially keen on the different degrees of ‘focus’ with some parts being sharp whereas others are much more blurred.

Two Worlds

I was thinking about the post World War I landscape and how the years after 1918 saw a surge in spiritualism with grieving parents, wives and children seeking solace in the idea of their loved ones’ continued existence on ‘the other side’. There is, I think, a link with the Pastoral landscapes I’ve been thinking about of late, a place which seems best expressed by the poet Rilke:

And gently she guides him through the vast Keening landscape, shows him temple columns, ruins of castles from which the Keening princes Once wisely governed the land. She shows him the towering trees of tears, the fields of melancholy in bloom (the living know this only in gentle leaf).

In tandem with this boom was the beginning of battlefield tours; tourists would visit the western front when the guns had hardly stopped firing. And I thought how interesting it was that there were these two different ways of looking for those who had gone: one, in a landscape of the imagination, the other, in the physical world; a pastoral plane and a place torn apart by war. And in many respects this reflects my work; the real world which we inhabit today and the plane of the past – a place in which we search for the dead in order that we might empathise with them.

Proposing Moments of Pastoral

Through my research on World War I, I’ve accumulated a large amount of data – postcards, quotes, maps, texts, photographs, personal thoughts and experiences – which I want to start distilling into a new body of work. To do that, I’ve been looking for a ‘lens’ through which I might look again at this archive and thus begin shaping my research into something I can use in a work.

Quotes

A lens could be anything; an image, an experience, a thought, or in this case a quote – or quotes. I’ve discussed them before, but here they are again, the first from Neil Hanson, the second, Paul Fussell:

“As the torrents of machine-gun bullets ripped through the grassy slopes up which the British troops were advancing, the smell of an English summer – fresh cut grass – filled the air. For thousands it would be the last scent they would ever smell.”

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

The smell of an English summer – fresh cut grass – and the idea of moments of pastoral come together to make a lens through which I can re-examine my research. I’ve used Neil Hanson’s quote before, as the title of a piece in 2007 (pictured below), but combined with Paul Fussell’s quote it becomes even more interesting.

The smell of fresh cut grass is a smell I often associate with the past, in particular, my childhood, and as a child, my notion of the past was a pastoral one. To me, the past was an unspoilt place, where squirrels could run the length of the country without touching the ground (a ‘fact’ I always loved). I loved the idea – and I still do – of untouched swathes of forest.

The past was always pastoral.

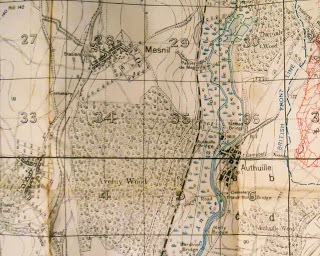

Maps

To pursue my pastoral fantasy, I would create maps of imagined landscapes (something I’ve also discussed numerous times before) and this too has become a lens through which to look at my research. When we think of those who fought in World War I, we often consider only their deaths. We don’t imagine their lives beforehand, especially the fact that not so long before the war, many were still children.

My maps were well-wooded.

As are the trench maps I have in my collection.

Postcards and gardens

There is a link therefore between a pastoral past, my childhood and the consideration of those who died in World War I as children years before – as real people who existed beyond the theatre of war.

This leads me to postcards, such as the one below:

This postcard shows a soldier posing with his mother(?) standing in what might have been his garden, in the place where, perhaps, he grew up as a child. I might not be able to empathise with him as a soldier directly, but I can well imagine his garden. Part of the landscape of my childhood comprises the gardens of my home and those of my grandparents, as well as parks and playing fields at school. They are pastoral landscapes in miniature, where the grass was cut on a summer’s day.

Proposing moments of pastoral

The question which I haven’t asked is: how do you propose moments of pastoral? The answer to this, I think, is crucial to the development of any work.

To propose is to suggest, invite. It is something given to another.

Maps are objects which propose. But what are they proposing? On the one hand, they propose journeys. More often than not, we use them to plan a journey in the future, for example a day trip or holiday. They require us to use our imaginations; to imagine the future, the landscape and our position within in. They can however propose journeys into the past. In a previous blog about Ivor Gurney, I wrote:

After returning from the war, Ivor Gurney, like so many others suffered a breakdown (he’d suffered his first in 1913) and a passage in Macfarlane’s book, which describes the visits to Gurney – within the Dartford asylum – by Helen Thomas, the widow of Edward Thomas is particularly moving. Helen took with her one of her husband’s Ordnance survey maps of Gloucestershire:

“She recalled afterwards that Gurney, on being shown the map, took it at once from her, and spread it out on his bed, in his hot little white-tiled room in the asylum, with the sunlight falling in patterns upon the floor. Then the two of them kneeled together by the bed and traced out, with their fingers, walks that they and Edward had taken in the past.”

The map they laid on the bed was one that showed the familiar trails and paths of the countryside. But it was also one which, like that I made in my childhood, gave Gurney access to his imagination – to his own past. Together, the patient and his visitor read it with their fingers, following the trails as one follows words on a page. A narrative of sorts was revealed, memories stitched together by the threads of roads, paths and trails.

Maps can also be used of course to orient ourselves in the present. We might consult them to find out where we are or where we ought to go. In fact, they can be used to orient ourselves in the past, present and future.

As an artist wishing to propose moments of pastoral, I want to use the form of the map as a starting point. The map might show a pastoral scene, using, for example, the ‘vocabulary’ of the trench map to show the trees.

The Past in Pastoral

July 1st 2016 will mark the 100th anniversary of the infamous Somme offensive. Having already made a lot of work about World War I, I want to mark this anniversary with some new pieces, working around the theme of ‘shared moments of pastoral’.

There have been numerous starting points which, in no particular order, I will outline below.

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.” Paul Fussell

“Here in the back garden of the trenches it is amazingly beautiful – the mud is dried to a pinky colour and upon the parapet, and through sandbags even, the green grass pushes up and waves in the breeze, while clots of bright dandelions, clover, thistles and twenty other plants flourish luxuriantly, brilliant growths of bright green against the pink earth. Nearly all the better trees have come out, and the birds sing all day in spite of shells and shrapnel…” Paul Nash

‘The next day, the regiment began the long march to the Front. In the heat of early summer, nature had made attempts to reclaim the violated ground and a deceptive air of somnolence lay on the landscape. “The fields over which the scythe has not passed for years are a mass of wild flowers. They bathe the trenches in a hot stream of scent,” “smelling to heaven like incense in the sun.” “Brimstone butterflies and chalk-blues flutter above the dugouts and settle on the green ooze of the shell holes.” “Then a bare field strewn with barbed wire, rusted to a sort of Titian red – out of which a hare came just now and sat up with fear in his eyes and the sun shining red through his ears. Then the trench… piled earth with groundsel and great flaming dandelions and chickweed and pimpernels running riot over it. Decayed sandbags, new sandbags, boards, dropped ammunition, empty tins, corrugated iron, a smell of boots and stagnant water and burnt powder and oil and men, the occasional bang of a rifle and the click of a bolt, the occasional crack of a bullet coming over, or the wailing diminuendo of a ricochet. And over everything, the larks… and on the other side, nothing but a mud wall, with a few dandelions against the sky, until you look over the top or through a periscope and then you see the barbed wire and more barbed wire, and then fields with larks in them, and then barbed wire again.”

As the torrents of machine-gun bullets ripped through the grassy slopes up which the British troops were advancing, the smell of an English summer – fresh cut grass – filled the air. For thousands it would be the last scent they would ever smell.’ Neil Hanson

“There was utter silence, broken only by the twitterings of the swallows darting back and forth.” Filip Muller on the murder of a friend in Auschwitz

Art is…

Art is the search for a ‘way-in’ to a subject and the artist’s role is in keeping that ‘way-in’ open so others might follow.

The Lawn and the Woods

I remember as a small boy how my Nana would on occasion take me and my older brother to where she worked as a Housekeeper. The house was – at far as I recall – a big, white, Modernist building with a large well-kept lawn at the rear. But what I remember most was the wood which stood at the edge of the garden. I can see it now – that contrast between the manicured lawn and the wild dark of the trees, and with the work that I’ve been doing on gardens, trees and contrasts, this particular memory has suddenly sprung to life.

Silence in the Woods

I’ve discussed previously, three extracts from newspapers in which a moment of silence serves to amplify all that happened before and after. To recap, those three extracts were [my italics in all]:

“On Sunday last, at the close of the evening service, the Society Meeting was held, and references to the death of Private Rogers were made by several members of the Church. Private Rogers’s mother is one of the oldest members of the Church. The meeting passed a vote of condolence with the relatives, all present standing in silence.” (1915)

“Shortly after dusk, the lightning appeared in the south and western horizon, and soon became most vivid, blue sheets of lightning following each other in rapid succession, but unaccompanied by thunder.” (1842)

“Her mother got up and tried the door but it was locked by [the] witness when her father and mother came in. Her father took the sword out of the sheath which he threw to the floor and then struck her mother on the back with the flat side of sword; neither her father nor mother spoke.” (1852)

In each of these three passages, the moment of silence is set in opposition to the text preceding it, and, as a result, it serves, as I’ve said, to amplify that text. As I was thinking about this, I became aware that the pieces of work, Heavy Water Sleep and The Woods, Breathing also reflected this opposition.

Both projects use a moment in the life of Adam Czerniakow. As I’ve written before:

“For almost three years, Adam Czerniakow was ‘mayor’ of the Warsaw Ghetto. One of the inspirations for this work is a line taken from his diary, which he kept whilst living in Warsaw in occupied Poland from 1939 to his death in 1942. On September 14th 1941 he wrote:

‘ In Otwock. The air, the woods, breathing.’

On occasion, Czerniakow was allowed to leave the ghetto to visit the Jewish Sanatorium at Otwock just outside Warsaw. It was one place he could find some respite from the horror and torment he endured in the ghetto.”

In reading his diary, this effort and the toll which it took on both his physical and mental health is evident and in these few words – the air, the woods, breathing – words with which we can easily identify, we can glimpse his relief at being able, just for a short time, to stand in the woods and breathe. In that simple, everyday, action we see the other side of his life; the world far beyond our own comprehension.

Czerniakow would also seek solace in reading. One night, on January 19th 1940, he wrote:

“…During the night I read a novel, ‘Pilgrims of the Wild’ – Grey Owl… The forest, little wild animals – a veritable Eden.”

Given what we know about the Holocaust and what Adam Czerniakow went through, these silent moments – in the woods at Otwock and reading at home – are set in stark contrast to what was going on around him. As a result, these two moments serve to amplify the horrors of the war; everything that had happened and everything that had yet to occur.

In my previous blog, I quoted Jorge Luis Borges who wrote:

“A single moment suffices to unlock the secrets of life, and the key to all secrets is History and only History, that eternal repetition and the beautiful name of horror.”

The word moment crops up a lot in my work, as it has in this entry. I’ve long thought that one can only empathise with people in the past through an awareness of present day moments – moments of the everyday. Borges’ quote seems to bear this out. In the case of Adam Czerniakow I have given two such moments. Then there are the three moments of silence in the passages above.

History is a cycle, an eternal repetition of single moments. When I read the same book that Czerniakow read (Pilgrims of the Wild) I am repeating that same single moment. Likewise, when I stand in a wood I am repeating another of those single moments.

So the silence amplifies History and the nature of that silence serves as a moment of connection with the past. The nature of silence and its opposition to violence is interesting too. I return to a favourite quote of mine:

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

Peace equates with pastoral, and, perhaps, with silence. I shall end with a quote from Rilke which also seems to fit with what I’ve been saying:

“Look, trees exist.

The houses we live in continue to stand. Only we

pass away like air traded for air and everything

conspires to maintain silence about us, perhaps

half out of shame, half out of unspeakable hope.”

Quote from Jorge Luis Borges

“A single moment suffices to unlock the secrets of life, and the key to all secrets is History and only History, that eternal repetition and the beautiful name of horror.” Jorge Luis Borges

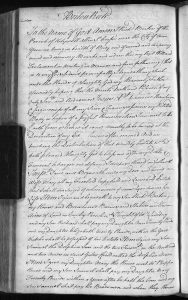

William Bishop (1794-1866)

Silence as Other

The past is silent. To know the past, one must know silence.

The theme of silence has come up a lot in my work, something I’ve written about before (see Augmenting Silence), and it was whilst re-reading a blog on Chinese painting that I began to consider – within the context of what I’d written – silence as other.

In that blog I wrote:

There’s a quote I’ve often used from Christopher Tilley. In his book, The Materiality of Stone – Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology, he writes:

The painter sees the trees and the trees see the painter, not because the trees have eyes, but because the trees affect, move the painter, become part of the painting that would be impossible without their presence. In this sense the trees have agency and are not merely passive objects… The trees ‘see’ the painter in a manner comparable to how a mirror ‘sees’ the painter: that is, the trees like the mirror, let him become visible: they define a point of view on him which renders for him something that would otherwise remain invisible – his outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence… the trees and mirror function as other.

Like the trees, the mountains share that agency; they too ‘see’ the painter’ and it’s almost as if the painting becomes a painting, not of Yu Jian looking at the mountains, but of the mountain ‘seeing’ Yu Jian. It’s not the mountain that is made visible on the paper, but the artist’s outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence.

I would add now, that, like the trees and the mountain described, silence works in the same way. To empathise with the past, as I’ve written many times before, we must understand what it means to be present, and silent meditation is a great way to do that. Sitting in the garden and listening in silence, one realises how silence comprises many ‘layers’ of sound (and other sensations); how the nowness of now comprises many ‘parts’.

The past too comprises many layers or parts, most of which have been stripped away by the very fact of their pastness. Now the past is silent, but by understanding that silence, we can find a way back.

Another blog entry (An Archaeology of the Moment) backs this up. In it I wrote how in his book Figuring it Out’ Professor Colin Renfrew writes:

The past reality too was made up of a complex of experiences and feelings, and it also was experienced by human beings similar in some ways to ourselves.

The way we experience the present then, tells us a great deal about how people experienced the past when it too was the present.

In a blog about a distant ancestor Thomas Noon (The Gesture of Mourning), I wrote about standing at the grave of him and his children who pre-deceased him; how he would have stood there:

“I can imagine him there, listening as I can to the wind in the trees. He sees the same late-winter sun and feels its warmth on his face. I can, as I have done, read about his children and their untimely deaths. I can read about him. But standing at their grave, my imagined versions of them are augmented by the gesture of my body.”

Back to the blog entry Augmenting Silence. In it I gave three extracts from old newspapers:

“On Sunday last, at the close of the evening service, the Society Meeting was held, and references to the death of Private Rogers were made by several members of the Church. Private Rogers’s mother is one of the oldest members of the Church. The meeting passed a vote of condolence with the relatives, all present standing in silence.” (1915)

“Shortly after dusk, the lightning appeared in the south and western horizon, and soon became most vivid, blue sheets of lightning following each other in rapid succession, but unaccompanied by thunder.” (1842)

“Her mother got up and tried the door but it was locked by [the] witness when her father and mother came in. Her father took the sword out of the sheath which he threw to the floor and then struck her mother on the back with the flat side of sword; neither her father nor mother spoke.” (1852)

What interested me about these quotes were the silences. When I became aware of them, I realised I was empathising with the story much more readily. I could almost sense myself in the amongst words and the scenes they described. To repeat what I wrote earlier:

“Like the trees, the mountains share that agency; they too ‘see’ the painter’ and it’s almost as if the painting becomes a painting, not of Yu Jian looking at the mountains, but of the mountain ‘seeing’ Yu Jian. It’s not the mountain that is made visible on the paper, but the artist’s outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence.”

If silence is ‘other’, how can it be shown in a work? The answer is revealed in the following from Augmenting Silence. As I wrote:

In all three quotes, the ‘revelation of silence’ comes after the ‘facts’:

“The meeting passed a vote of condolence with the relatives, all present standing in silence.”

“Her father took the sword out of the sheath which he threw to the floor and then struck her mother on the back with the flat side of sword; neither her father nor mother spoke.”

“…the lightning appeared in the south and western horizon… but unaccompanied by thunder.” Silence is not the subject of the texts, but a part which serves to illuminate the whole (which in the second extract is especially pertinent).

It’s like the opening of a camera’s shutter; everything that came before it is condensed into a moment.

Also, as I looked into my work, I realised that ‘silence’ appeared in ‘Heavy Water Sleep‘:

Outside a window stands silent, the surrounding

covered with heavy water sleep.

There is no sound and no movement

dropping through the

closed rude

earth.

a man advancing with resolute step

But for the heavy steps,

there is silence.

time Meanwhile

emerges

from a hole in the day before

and

pulls impatiently

at the window stops Outside

the so-lately deserted

Silence

the Extraordinary story

that lies behind this scene

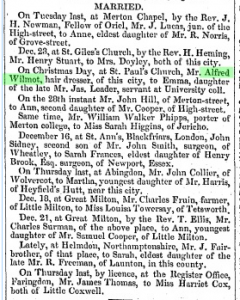

Alfred Wilmot

Having photographed the grave of Henry Sides, I took one of another grave which had caught my eye whilst walking the same path. This belonged to an Alfred Wilmot:

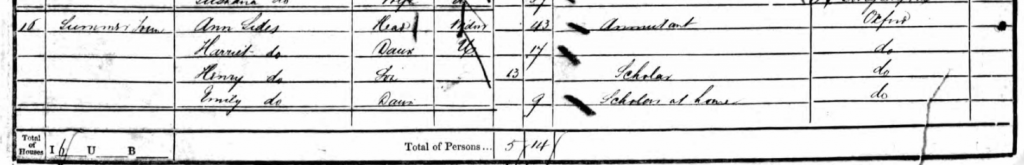

Harriet Sides

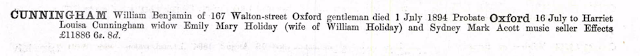

Harriet Sides was the eldest daughter of Henry Sides. Born in 1834 she was married to William Cunningham in 1871 age 37. William Cunningham was born in 1826 in London to a William and Mary Cunningham and in 1861 is shown to be living at 20 Broad Street, Oxford.

In 1881, Harriet and William were living in Kidlington, Oxford with their two children, Clifford (6) and Walter (4). In 1891 they were living at 167 Walton Street, Oxford along with their two children and a servant, Clara Seppury.

William died on 1 July 1894 leaving £11,886 6s 8d in his will – almost £1.4 million in today’s money.

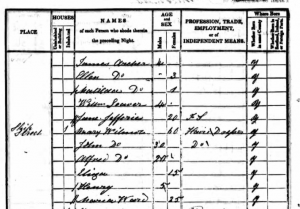

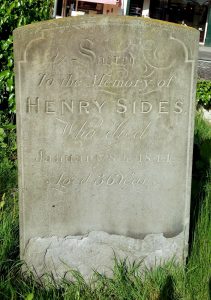

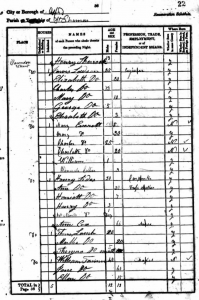

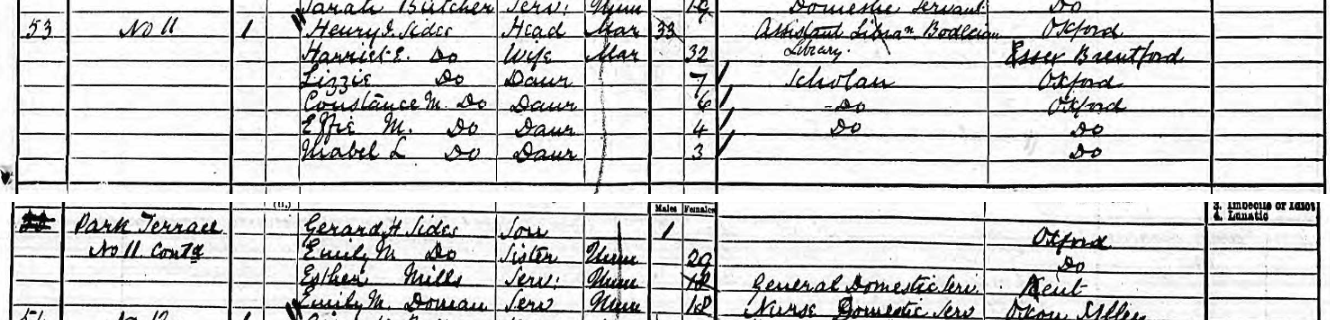

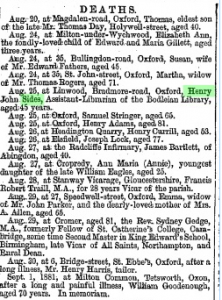

Henry Sides and family

Everyday, on my way to catch the bus after work, I pass by this grave at the edge of the path which cuts through St Giles churchyard.

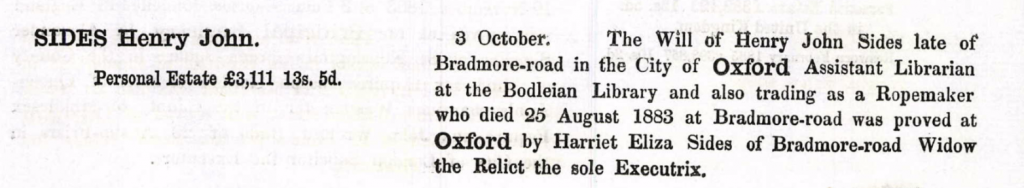

Ten years on, in 1881, Henry and Harriet have extended their family still further, with the arrivals of Arthur, Herbert, Gertrude and Archibald. They had moved too, living now in Bradmore Road with a Cook and a Nursemaid. At 42, Henry is still an assistant librarian and partner in a firm of rope makers.

Henry John Sides died on 25th August 1883, aged just 45…

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- …

- 31

- Next Page »