The Dolphin Inn (now demolished), which was run by my 6 x great-grandfather Samuel Stevens between (at least) 1734-1772. The photograph of the inn was taken some time around 1870; the modern photograph on my way to work today.

The Dolphin Inn

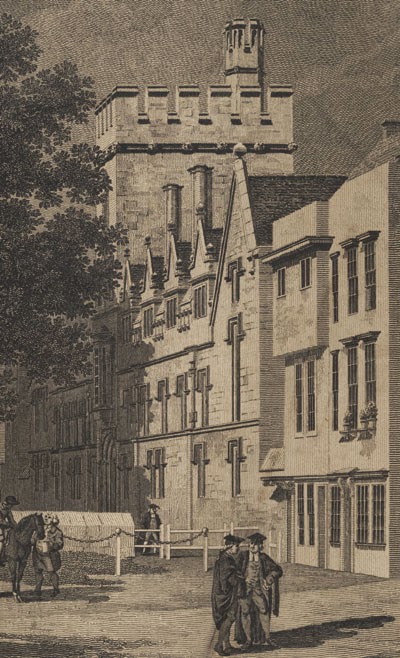

After my last post about my 6 x great-grandfather, Samuel Borton’s residence, I wanted to see if I could find out the name of the inn he owned, which, I now knew stood at the southern end of St. Giles. In a book of old Oxford photographs, which I bought a few years back, I found the following image:

It shows St. John’s college and a building next door called the Dolphin building, which at the time of this photograph c1870 was part of the college. The text beneath the photograph stated that it had once been an inn, and digging a little deeper, I discovered that it had indeed been the Dolphin Inn.

This then is a photograph of my 6 x great-grandfather’s inn before it was demolished.

The engraving below, is that of the same inn, made in 1779, probably at the time when my ancestor was resident.

More on Samuel Borton in 1772

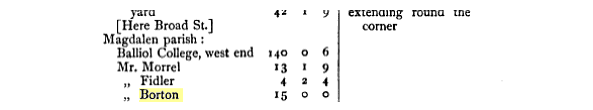

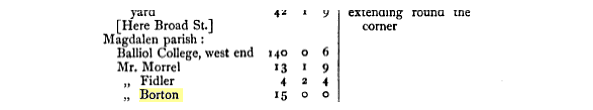

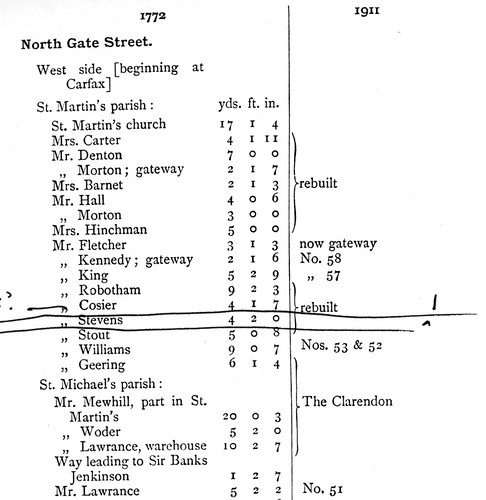

Following on from my last post on Samuel Borton’s residence, I’ve found evidence confirming where he lived. The following image shows his name in the survey:

I took the photo below whilst standing in my bus queue this evening. It shows the row of buildings which, I believe, stand on the site of those buildings once occupied by Messrs Morrel, Fidler and my ancestor, Borton.

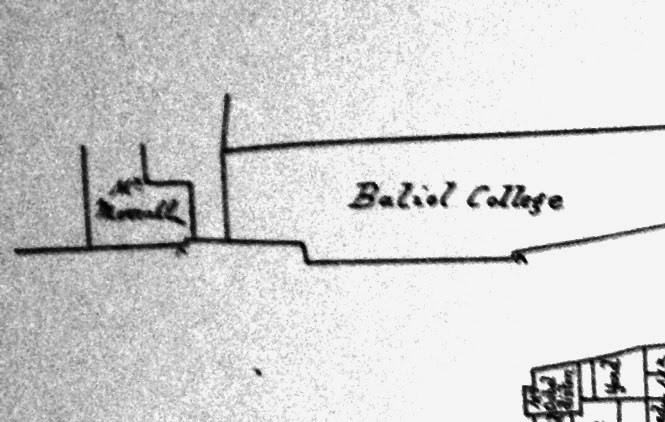

Looking at a plan from the 1772 survey – which I’d photocopied several years ago – I discovered that this is indeed the site of my ancestors dwelling.

The following is a close up of the top left hand corner.

The name in the ‘box’ next to Balliol College is Mr. Morrell, which when we look at the list at the top of the page is the first name after Balliol College. His property would have stood approximately where the orange-brown neo-classical building stands now. Four yards to the left would have been Mr Fidler’s property and occupying the land next to that would have been my ancestor’s property, which I believe was an inn.

Samuel Borton in 1772

I have recently written about John Gwynn’s survey of Oxford (1772) in relation to my family tree research (see Lydia Stevens 1734-1822) and have discovered another ancestor in the same survey. Lydia’s father, Samuel Borton was, at the time of her birth, an innkeeper in Mary Magdalen Parish. Lydia married John Stevens in the church of St. Mary Magdalen in 1764, and I wondered therefore whether Samuel Borton would be listed in Gwynn’s survey? Sure enough, in Magdalen parish, close to Balliol College, a Mr. Borton is listed as the owner of a property measuring 15 yards wide.

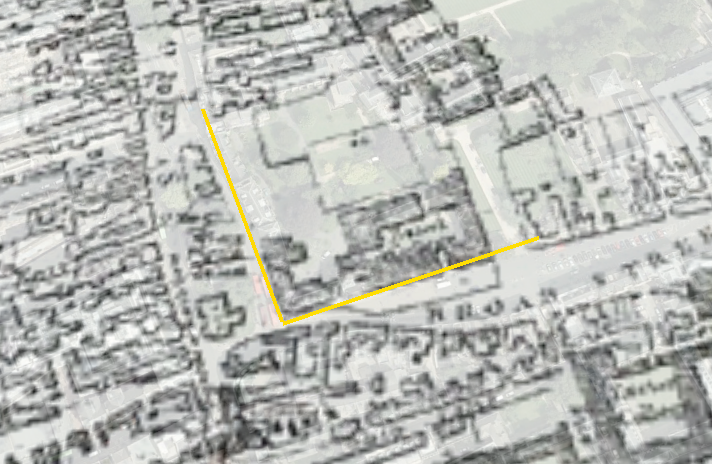

I need to get a copy of H.E. Salter’s Survey of Oxford in 1772 with Maps and Plans to work out where exactly this is (the above extract is from Google books). However, it might be that as we have [Here Broad St.] and given that the length of Balliol College is given as 140 yards (128 metres), that Mr. Borton’s property is on the north side Broad Street. But then Balliol College, west end would seem to be that part of the college shown in yellow below. In which case Mr. Borton’s property would actually be nearer St. Giles.

Having looked up Broad Street in Google Earth, I decided to use the measuring tool to see if that would help. The yellow lines are both approximately 140 yards long.

Superimposing the 1750 map above onto Google Earth, we get the following:

A closer look:

Samuel Borton (1706 – ?)

During a quick research session in the library this lunchtime, I tried to discover the birth date of my 6 x great-grandfather, Samuel Borton. Having trawled through the indexes for St. Martin’s parish, St. Mary Magdalen, St. Peter le Bailey and St. Mary the Virgin, I turned to that for Holywell parish. In there I discovered a Samuel Borton born in 1706. His father was listed as Richard and in the time I had, I discovered two siblings called Ann (b.1693) and Mary (b.1703).

From the index it’s hard to say for sure that this Richard Borton is the father of my Samuel Borton, but the name isn’t common and, in line with what I described yesterday, another piece of evidence could be gleaned from the names of Samuel’s own children.

His first son was called Samuel (1737 – ); his second son, surely named after his grandfather – Richard, born in 1739.

John and Samuel

The name of a first born son or daughter is a good way of confirming whether or not your research, as regards a particular family line, is on the right track, and this has been the case with my current research into the Stevens line (my mother’s father’s line) of my family tree.

The father of my 3 x great-grandfather, John Stevens (1811-1876) was, I believe, a Samuel Stevens (1776-1841) and his father in turn was another John Stevens (1737-1803).

The name John is clearly important. John (1737-1803) named his first son John. He appears to have died in infancy as John’s fourth son (seventh child) was also named John. Sadly, this child also seems to have died in infancy; the couple’s fifth son (eighth child) was also named John. The couple’s third son (fourth child) was named Samuel (b1769) who again appears to have died in childhood. Another Samuel (my direct ancestor and the couple’s ninth child) was born seven years later in 1776. This shows that the name Samuel was also important.

This Samuel (1776-1841) had several children including a Samuel (first son, born in 1808) and a John (my direct ancestor born in 1811). John also had many children; his first born was John (1837-1888) and his second son was Samuel (1839-1919). My direct ancestor, Jabez (1847-1899) also had children, none of whom were called John or Samuel. Indeed, the name doesn’t appear again in my direct family line. One reason for this falling out of favour might be that John Stevens (1837-1888) spent much of the last part of his life in Moulsford Asylum. With the loss of his income his wife Emma entered a workhouse with two of her children, Martha and Kate, where she died of cancer in 1873.

The important point is that my 3 x great-grandfather’s second son was Samuel; it links him with the Samuel Stevens who I believe to be my 4 x great-grandfather. But where does the name Samuel come from? Why was it so important?

Going through the Oxfordshire parish indexes last week I discovered the following: my 5 x great-grandfather John Stevens (1737-1803) was married to Lydia Borton (1734-1822) in the church of St. Mary Magdalen on 24th March 1764. The witnesses are given as Sam Borton and Mary Stevens. In the records I discovered that Lydia’s father was Samuel Borton, an innkeeper in the parish of St. Mary Magdalen. So, that must be where the name comes from as regards its important in the Stevens line.

The elusive Samuel Stevens (1776 – ?)

I’ve turned my attention to my 4 x great-grandfather Samuel Stevens who I know was born in Oxford in 1776. I know too that he married a woman called Mary and that they had a child called John (my 3 x great-grandfather) in 1811.

In the library this afternoon I tried to find details of other children they might have had and the date and location of their wedding; however I couldn’t find anything save for details of a daughter, Frances, born in St. Aldate’s Parish in 1809, two years before John. However that was it, which led me to suspect that either one or both had died after John’s birth, or that they had moved away – which seemed the more likely.

Given that John lived in Reading for much of his life, it seemed plausible that it was actually his parents who moved some time after his birth in 1811. Searching through the records online, I eventually found a Samuel Stevens who married a Mary Pecover in St. Lawrence Parish, Reading on May 14th 1807. This I’m sure must be my ancestor; not only does the place fit – along with the name of his wife – but the date of the wedding – two years before the birth of Frances – also fits the wider picture. It seems therefore that having married Mary in Reading, they moved to Oxford but left shortly after to return to Reading.

The (Georgian) Stevens Family

Having done a bit more research in the library this afternoon, I believe I have discovered the dates of birth and death of Lydia Stevens’ husband John.

I know he died before Lydia (1822) and that he was alive in 1777 when his son William was born. Looking through the parish registers for St. Martin’s (the parish in which Lydia lived at the time of her death) I discovered a John Stevens who died in 1803 at the age of 66. This would put his birth year at 1737: Lydia, his widow, was born in 1734/5 which leads me to think that this is indeed my John.

I then looked at their children and found the following, all baptised in the same parish:

- Lydia Stevens (Jan 18 1765)

- John Stevens (Dec 26 1765)

- Samuel Stevens (Jan 29 1767)

- James Stevens (Oct 23 1768)

- Frances Stevens (May 15 1770)

- Mary Stevens (Sep 28 1771)

- John Stevens (Aug 20 1773)

- John Stevens (Dec 1 1774)

- Samuel Stevens (Apr 4 1776)

- William Stevens (Dec 31 1777)

Given that there are 3 Johns and 2 Samuels, one can assume that the first John died some time before 1773 and that the second John died before 1774. Clearly the name John was important which leads me to believe that John’s father might have been called John as well.

The first Samuel must have died some time before 1776 when my direct ancestor was born.

Looking again at the wedding of John and Lydia, I found that the witnesses were Sam Borton and Mary Stevens. I’ve no idea of course what their relationship was to the couple; Sam could have been Lydia’s father or brother, but clearly the name Samuel or Sam was important and seems to have come from that side of the family. Mary Stevens might have been John’s mother or sister. The couple’s third daughter was named Mary so I’m no clearer on whether this was John’s mother’s name or not.

Lydia Stevens (1734-1822)

Researching John Stevens in the library today, I found what I’m sure must be his parents. Having looked at the Index of Baptisms for the time around his birth (1811) I found only one person matching his dates. John Stevens was born on 7th October 1811 in St. Aldate’s parish. His parents are given as Samuel and Mary Stevens, and looking at John Stevens’ children, I found that his second born son is named Samuel (his first son is called John). I decided to see if I could locate a Samuel Stevens in the Parish Registers. I couldn’t be sure that he was born in the city but it seemed quite likely. Sure enough I found a Samuel Stevens born on the 4th April 1776, baptised in St. Martin’s (now demolished). His parents were given as John and Lydia Stevens and so I looked for a record of their marriage in the city. Again my luck was in and I found that they were married on March 24th 1764 in St. Mary Magdalen. Lydia’s maiden name was Borton and the witnesses at the wedding were Sam Borton and Mary Stevens. John is described as being from St. Martin’s which is where Samuel was baptised.

At the same time I also wrote the following:

A year or so ago, I started work on a piece of work based around John Gwynn’s survey of 1772. The piece was called (as a working title) ‘6 Yards 0 Feet 6 inches’ based on the measurement of John Malchair‘s home in Broad Street. Having discovered an ancestor – John Stevens – born in the city in 1811, I wondered if there was any chance that one of the Mr Stevens’ listed on the survey was an ancestor of mine? It seemed a long shot but after today’s research I’m rather more optimistic.

If I did have an ancestor in Oxford at the time of the survey and if my research is correct, then that ancestor would be John Steven, the grandfather of the one previously mentioned. I’ve no idea when he was born but I do know that he was married in 1764 and is described as coming from St. Martin’s Parish, where his son Samuel, John Jr’s father was baptised in 1776. One could assume therefore that I did indeed have ancestors living in the parish of St. Martin’s at the time of the survey.

The images below are taken from the survey and show two Stevens one of which might well be my ancestor.

Gwynn fails to include (at least on the copy I have) first names from the survey but within the parish of St Martin’s two Mr Stevens are recorded along with a Mrs Stevens. One can assume however, that those most likely to be mine are the two Mr Stevens mentioned as living in the parish, one in Butcherrow (now Queen Street), the other in North Gate Street (now Cornmarket). The residence in Butcherrow is 7 yards 0 feet and 6 inches. That in North Gate Street is 4 yards 2 feet 0 inches.

Of course more work is required to see if one of these is indeed my ancestor, but I must admit to being very inspired by the prospect.

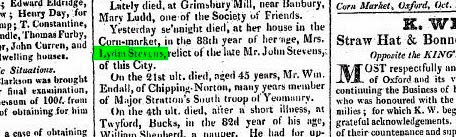

Yesterday, I was looking through Jackson’s Oxford Journal online and decided to search for a number of my ancestors. I’d already done as much with the Hedges side of the family (discovering in the process that they were often in trouble – see ‘The Victorians‘) and decided to check on my maternal side. I searched for Lydia Stevens (my 5 x great-grandmother) and discovered the following from an edition of the newspaper printed on November 2nd 1822:

‘Yesterday se’nnight [a week] died, at her house in the Corn-market, in the 88th year of her age, Mrs. Lydia Stevens, relict [widow] of the late Mr. John. Stevens, of this city.’

Not only did this notice give me her dates of birth and death (1734 – Friday, 25th October 1822), it also seemed to indicate that the Mr. Stevens recorded in John Gwynn’s survey on 1772 was my 5 x great-grandfather. Of course there is a 50 year gap between the date of the survey and the date of Lydia’s death, but it seems quite probable nonetheless.

War and The Pastoral Landscape

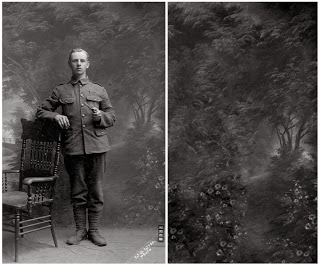

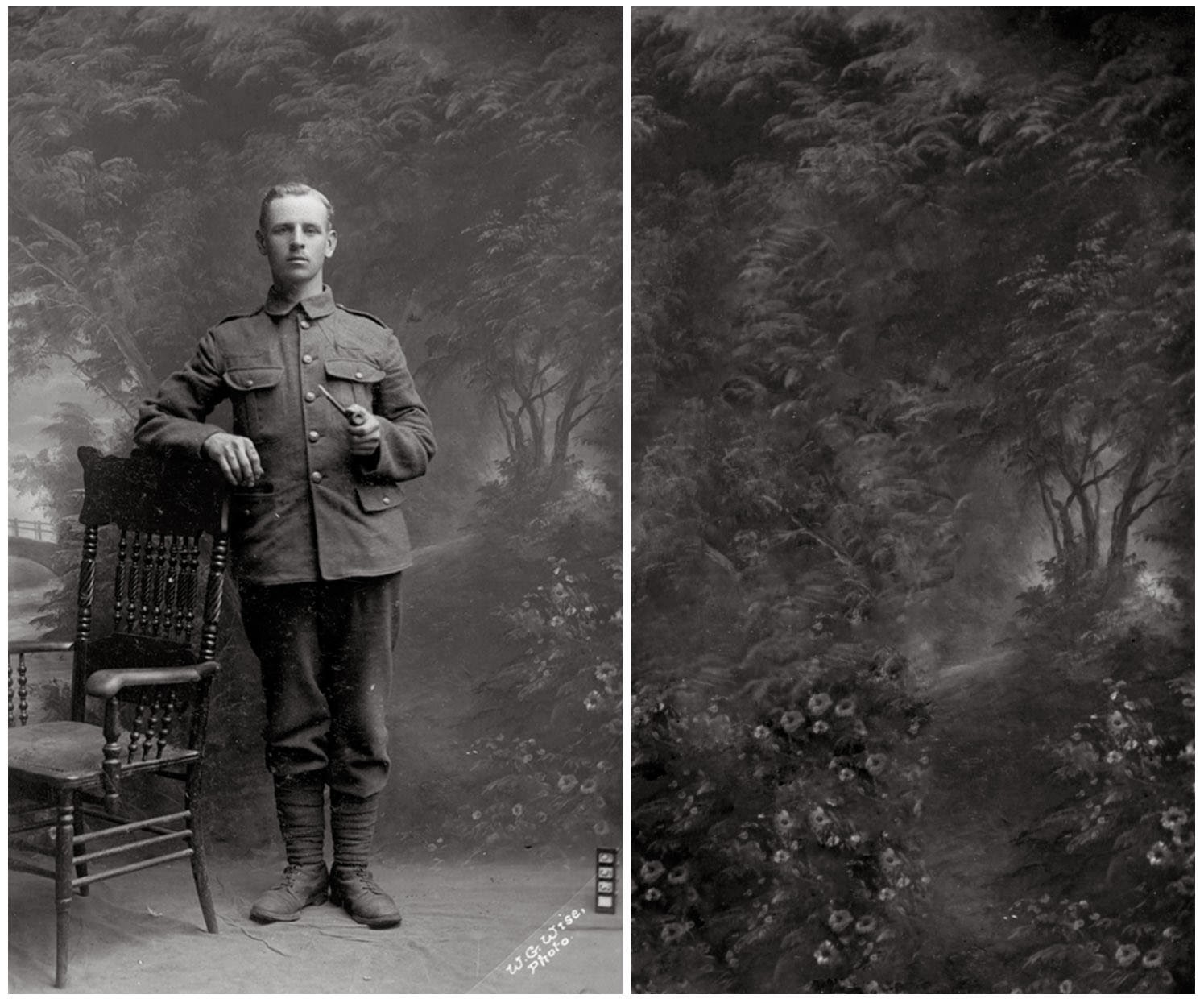

I’ve been thinking these last few weeks about a new body of work based on the First World War. For a long time – as will be evident from my blog – I’ve been looking at ways of using the backdrops of numerous World War I postcards.

A quote from Paul Fussell has been especially helpful in this regard.

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

The images on the backdrops are these proposed moments.

As a contemporary artist living so long after the war, it is of course impossible for me to create works about the war itself. What I can do however is comment on my relationship to the war (and those affected by it) by creating scenes – pastoral scenes – which use as their starting point the backdrops of World War I postcards.

The pastoral will, therefore, be articulated through the language of war.

These pastoral images will, predominantly, be woodscapes based on places I have visited over the last few years including Hafodyrynys (where my great-great-uncle, Jonah Rogers (1892-1915) grew up), Verdun and the Somme. They might contain – to quote Rilke – ‘…temple columns, ruins of castles’ as per the slightly less pastoral backdrops. They will be devoid of people; the soldiers absent as if they had melted into the backdrops – as if these pastoral scenes represent the Keening landscape of Rilke’s Duino Elegies.

As I’ve written before: it is this absence which the trees express so silently, so eloquently. As Rilke so perfectly puts it:

‘Look, trees exist.

The houses we live in continue to stand. Only we

pass away like air traded for air and everything

conspires to maintain silence about us, perhaps

half out of shame, half out of unspeakable hope.’

The woods I paint will be based, as I’ve said, on those places I have visited as well as those idealised scenes in front of which the soldiers stand in the postcards. They will be – as Richard Hayman puts it – woods “poised between reality and imagination…” – shame and unspeakable hope.

Again as I’ve written before: After the war, the sense of emptiness must have been everywhere. Every insignificant moment – barely acknowledged before the war – now pregnant with a sense of incomprehensible loss. The world, outwardly the same, had shifted just a little, but it had taken the lives of millions to push it there.

There is in this text a sense of absence but also of movement, of continuation – however slight or small (something I want to record in my work). And there’s a link between this and a quote from William Wordsworth who wrote in his Guide to the District of the Lakes: we can only imagine ‘the primeval woods shedding and renewing their leaves with no human eye to notice or human heart to regret or welcome the change.’ I somehow want to turn this quote on its head and borrow from Rilke, who in his Duino Elegies describes the towering trees of tears. I want to paint scenes where there are no people, but in which their absence is recorded, primarily by the trees silently remembering.

“The painter sees the trees, the trees see the painter.”

T.S. Eliot (2)

Burnt Norton

And all is always now. Words strain,

Crack and sometimes break, under the burden,

Under the tension, slip, slide, perish,

Decay with imprecision, will not stay in place,

Will not stay still. Shrieking voices

Scolding, mocking, or merely chattering,

Always assail them.

T.S. Eliot

East Coker

There is, it seems to us,

At best, only a limited value

In the knowledge derived from experience.

The knowledge imposes a pattern, and falsifies,

For the pattern is new in every moment

And every moment is a new and shocking

Valuation of all we have been. We are only undeceived

Of that which, deceiving, could no longer harm.

In the middle, not only in the middle of the way

But all the way, in a dark wood, in a bramble,

On the edge of a grimpen, where is no secure foothold,

And menaced by monsters, fancy lights,

Risking enchantment. Do not let me hear

Of the wisdom of old men, but rather of their folly,

Their fear of fear and frenzy, their fear of possession,

Goethean Observation: Compost Heap

The compost heap is some eight feet in circumference and about three feet high at its highest point. It comprises many different types of vegetative matter, at a glance; apples, the branches of the Christmas tree, twigs, cut-down shrubs, leaves and soil. There are numerous stones too, snail shells and new plants.

[a crow calls behind me]The apples are in various states of decay, from ripe (and seemingly edible) down through papery brown to black. The black apples, split open, remind me of old leather shoes such as those you might find in a museum.

The sun catches the left-hand side of the heap [a blackbird is calling above the traffic]. There is also a piece of plastic – white and dirty. As I look more closely, I see a number of roots, rusty-brown in colour, stretching across the pile. The wind agitates some of the lighter twigs and the leaves which still cling to their branches. The colour of the leaves is pretty much uniform; brown to darker brown, and with all the dampness of the outer part of the pile – almost black., like the most decayed apples.

The crown of the compost heap is covered with lighter branches no more than a centimetre in diameter.

They stick out to the left of the heap like the spines / quills of a porcupine. Tangled within them are clumps of earth intermingled with dried grass – now the same shadow of brown as the branches. The colour of the heap, taken as a whole is the dark brown of those darkest leaves. (*From a distance of ten feet or so, the compost heap is a single entity onto which some things have fallen. It is predominantly a dark brown colour, but as one approaches, it forms fragments, as those things of which it’s comprised throw out their shapes towards my incoming eyes.)

A few yellowish-green apples prick it and from these the eye gravitates towards the browner types, wrinkled and spotted/flecked. One apple looks like it is made of paper, its skin depressed as if a thumb and forefinger has marked it so.

There is a definite boundary between where the compost heap begins/ends and the rest of the garden, but looking more closely that boundary isn’t as stark as grass and dandelion and other small plants start to encroach. Parts of the heap too have tumbled beyond this boundary.

Near my foot, a black apple has burst its skin and inside, its brown flesh looks like tapenade.

[The crow, sitting on a rooftop behind to my left is persistent in his calling. I can hear too the whistle of a wood pigeon’s wings.]The compost heap although an entity in its own right comprises thousands of different things. A bright apple catches the sun and is made brighter sill.

Walking around I take up position to the left of where I’ve been. I can see a plastic straw – so at odds with the rest of the heap. A piece of flower pot seems however quite at home next to the apples – large and bruised, brown and putrid. There is a beautiful apple – a pale rust colour ridged and wrinkled, spotted with tiny white fungi. Above that, another rotting apple has abandoned its shape altogether and is now a dollop of brown, gooey flesh.

The core of the compost heap is more exposed here, and upon it, tiny green weeds have planted themselves.

[I have in my head the image of a star – perhaps because of the apples; their spherical shapes and the stages of their decay which go hand in hand – towards their implosion – with their different colours, ending at black, like black holes.]Around the compost heap is the rest of the garden – the shed, the apple tree, the lawn and the cracked path, on which I am currently sitting.

I cannot smell the compost heap – at least not from where I’m sitting. I move closer and breathe in and see two decaying rose-hips each of which comprises a myriad number of colours and shades. I step around it. The branches crack beneath my feet like branches in a fire. I notice too the thorns snagging the air which agitates the hair-like splinters of some of the branches.

The compost heap makes no sound – at least not that I can hear. Without the breeze it would seem entirely still, a fact belied by its very appearance, vis a vis its changing parts.

Pine needles from the Christmas tree are caked in the mud, a small pool of water has collected inside a hollow eaten out of an apple. The apple behind it appears almost turquoise. Holes in others are perfectly round. The wrinkled skin of some of the apples appear almost like human skin – that of the old.

The perfect shape of the empty snail shell – the random shape of decay.

Part 2

Looking at the papery brown apple, one imagines its flesh returning to fill the depressions in its skin. One imagines its skin colour changing as the apple itself grows bigger, becoming once again green like some of those around it. Freed of the mud gathered around it, it returns to the tree and begins to grow smaller in size until it becomes a blossom, then a bud on a branch in the summer. If it was left now (in its present state), it would over time reduce further still becoming just a collection of pips from which in time other trees would grow.

The branches of the Christmas tree once hung with decorations, bought from a shop, cut down in a forest or a managed plantation. How old was it? You can see the rings in the branches like ripples on a pond. They decrease to nothing, the tree folds itself away, takes refuge in the soil.

The empty snail shells would have their snails, the cut down branches would await the spring when they could surge with sap and grow.

But this compost heap isn’t dead. Nothing is dying here. When it was ‘fresh’ after I had finished gardening last year, it was four times the size. Some of it has been packed up and recycled, but much of it has reduced. There is still colour, even in the blackest apples. There is still shape, fragile like the snail shells.

Left to its own devices the heap would disappear entirely, but what would have disappeared exactly? In the end nothing truly disappears. Familiar shapes change.

The compost heap is never still and never silent, it changes by degrees which we cannot perceive, as with our own faces ageing in the mirror every day.

The leaves too would drift and change their colour, their shape, joining the tree again. Rewinding time they disappear. Fast-forwarding time they disappear but something remains.

Only the plastic straw will stay the same, not knowing what to do. The plastic straw is the one thing that’s truly dead.

Part 3

Feeding on itself.

It is what it consumes, its roots are the flows of energy released into the soil.

Colours are consumed.

It is blind. Deaf.

It feels. Drawing in to its core.

A star imploding.

All that will remain is the memory of its having been there.

It is for the most part invisible.

Just as it cannot see, we cannot truly see it, for it isn’t the shape of its composite parts – the apples, the branches, the clods of earth and pine needles. It is a flow – a slow progress of energy, released by colours, shapes to its heart, to the soil.

The compost heap is a pulse. It is the most un-dead thing in the garden.

It is a conduit.

It is slow, but far from dead.

Absence

In the Tenth Elegy of Rilke’s Duino Elegies we read:

‘…Our ancestors

worked the mines, up there in the mountain range.

Among men, sometimes you still find polished lumps

of original grief or – erupted from an ancient volcano –

a petrified clinker of rage. Yes. That came

from up there. Once we were rich in such things…’

And gently she guides him through the vast

Keening landscape, shows him temple columns,

ruins of castles from which the Keening princes

Once wisely governed the land. She shows him

the towering trees of tears, the fields of melancholy

in bloom (the living know this only in gentle leaf).

And she shows him grazing herds of mourning

and sometimes a startled bird draws far off

and scrawls flatly across their upturned gaze

and flies an image of its solitary cry….

Dizzied still by his early death, the youth’s eyes

can hardly grasp it. But her gaze frightens

an owl from the crown’s brim so it brushes

slow strokes downwards on the cheek – the one

with the fullest curve – and faintly,

in death’s newly sharpened sense of hearing,

as on a double and unfolded page,

it sketches for him the indescribable outline.

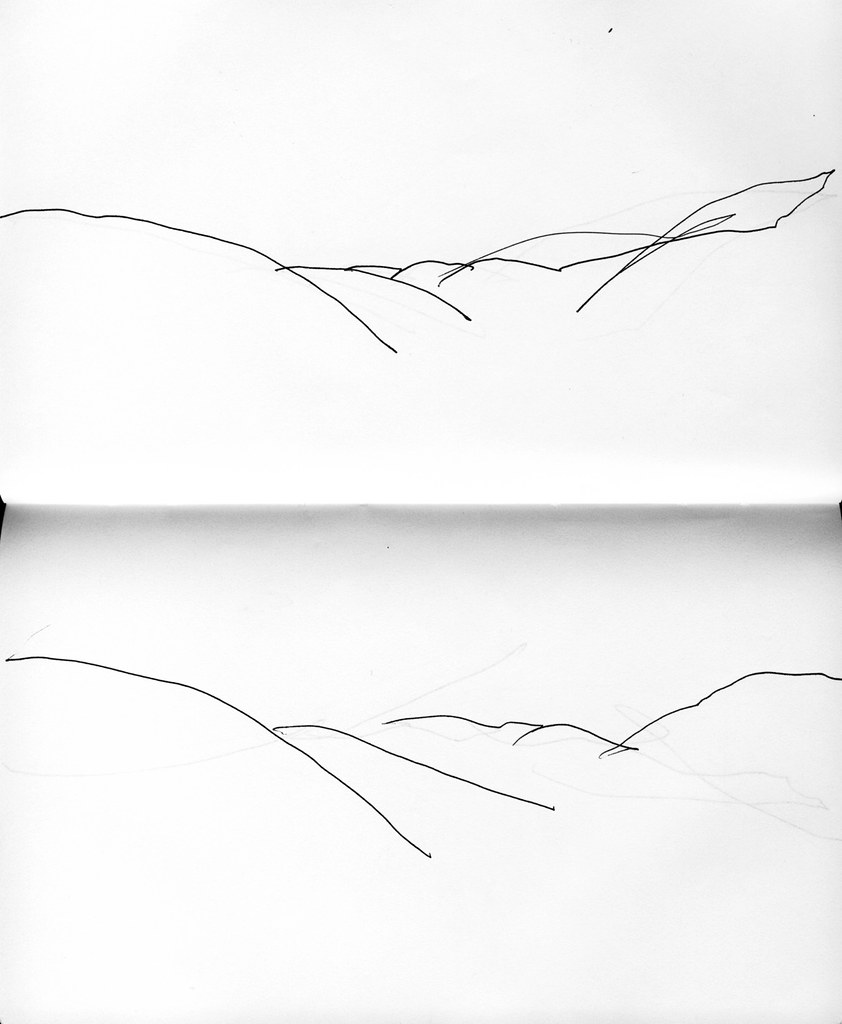

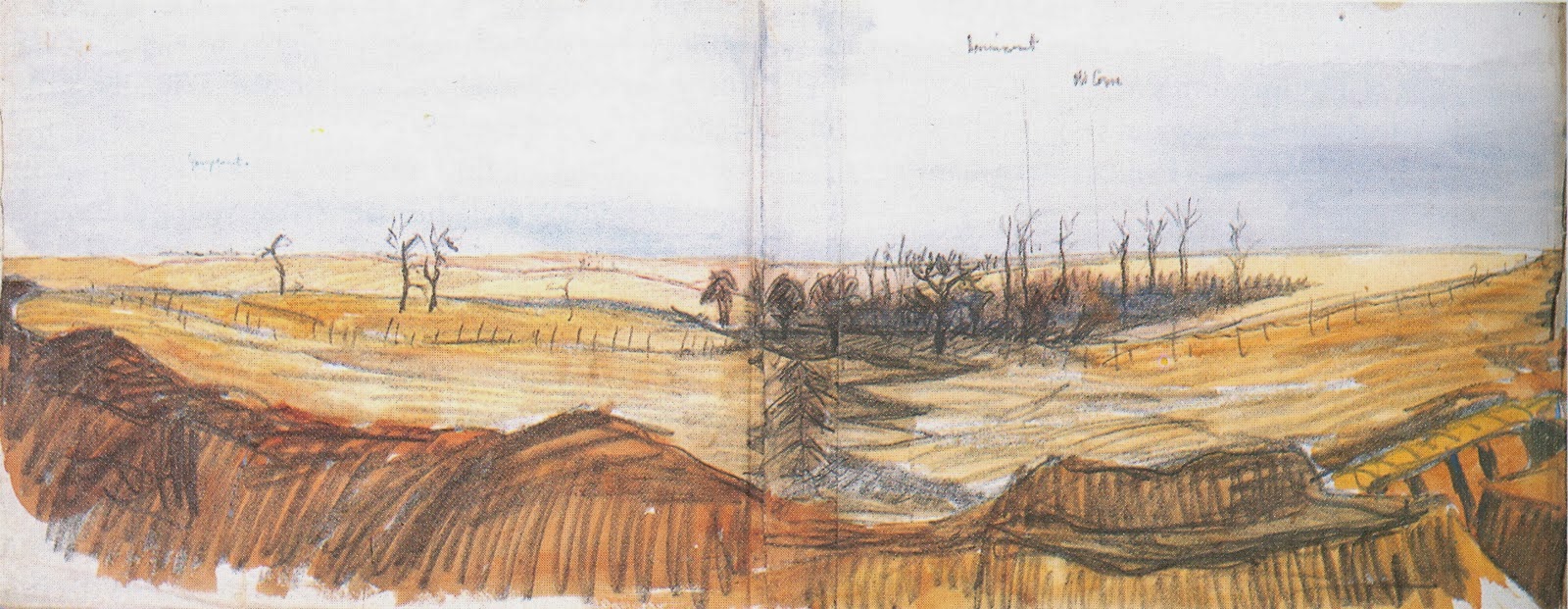

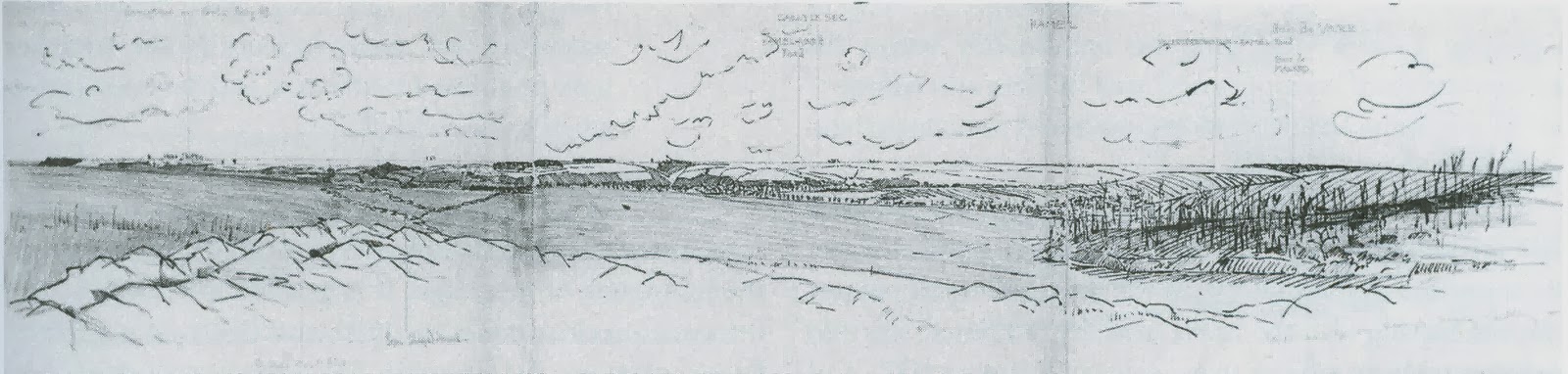

I’ve read this poem numerous times but on a recent reading, the first and last two lines reminded me of some sketches I made during a visit to Hafodyrynys, a town in Wales where my grandmother was born. My great-grandfather, Elias, used to walk from their house, up ‘the mountain’ as my grandmother called it, to Llanhilleth where he worked in the mine. Following in his footsteps, and walking the path he walked almost every day over 100 years ago, I thought of how the shape of the view had barely changed. I sketched it: an indescribable outline on a double and unfolded page.

A young boy in a flat cap pulled over his face

A bell tolls

A girl on her computer sits at the window looking out

Blue, yellow and white balloons

Two distant blasts of a train horn made bigger by the stillness of the air

The cackle of a bird

With regards gesture: Rilke said that the “depth of time” was revealed more in human gestures than in archaeological remains or fossilised organisms. The gesture is a “fossil of movement”; it is, at the same time, the very mark of the fleeting present and of desire in which our future is formed.

The concept of a ‘depth of time’ leads me to consider the phrase ‘a distant past’. How can the past be distant (or otherwise) if the past no longer exists? How can we measure that which we cannot empirically observe? My getting up this morning is as much a part of the past as, for example, the death of Richard III, yet of course there is a difference; a scale of pastness. But how can we measure pastness? We can of course use degrees of time, seconds through to years and millennia, but somehow it seems inadequate. For me, pastness can also be expressed through absence (in particular that of people) and it is this absence which the trees express so silently, so eloquently. “William Wordsworth, writing in his Guide to the District of the Lakes, wrote that we can only imagine ‘the primeval woods shedding and renewing their leaves with no human eye to notice or human heart to regret or welcome the change.'”

‘Look,’ says Rilke, ‘trees exist.

The houses we live in continue to stand. Only we

pass away like air traded for air and everything

conspires to maintain silence about us, perhaps

half out of shame, half out of unspeakable hope.’

When speaking of distance in relation to the past (the distant past), I think of distance as it’s perceived in the landscape; a measurement defining the space between me and something else. Putting the two together, the ‘distant past’ becomes something internal, carried in relation to the external world; the sum of those absences I carry through the landscape.

Rilke’s description of the Keening landscape reminded me too of the landscapes which I created as a child (see also Maps). These were ‘places’ based on how I perceived the landscape of the past; in particular, its swathes of ancient and unspoiled forests. As Richard Hayman puts it: “woods are poised between reality and imagination…” Whenever I was in a wood – however small – I always experienced it with my imagination.

Which brings me round to recent work I’ve been doing on World War I backdrops.

Seeing the young soldier standing before a bucolic backdrop, one is reminded of the youth in Rilke’s poem being led through the Keening landscape.

For some time, I’ve been wanting to create landscapes based on these postcards, landscapes about the Great War which do not seek to illustrate its horrors but articulate our present day relationship to it. A quote by Paul Fussell is important in this respect:

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

The landscape behind the soldier becomes the Keening landscape described by Rilke, a moment of pastoral as described by Fussell. In the right hand image, the soldier has gone; the landscape is one filled with ‘the towering trees of tears, the fields of melancholy.’ It is an image of the past: as Ruskin wrote: a tree “is always telling us about the past, never about the future.” It is an image of absence, a kind of which only the trees can speak.

Chaos Decoratif

Paul Fussell Quote

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

Taken from ‘A Terrible Beauty’ by Paul Gough

Paul Nash Quote

“Here in the back garden of the trenches it is amazingly beautiful – the mud is dried to a pinky colour and upon the parapet, and through sandbags even, the green grass pushes up and waves in the breeze, while clots of bright dandelions, clover, thistles and twenty other plants flourish luxuriantly, brilliant growths of bright green against the pink earth. Nearly all the better trees have come out, and the birds sing all day in spite of shells and shrapnel…”

Paul Maze (1887-1979)

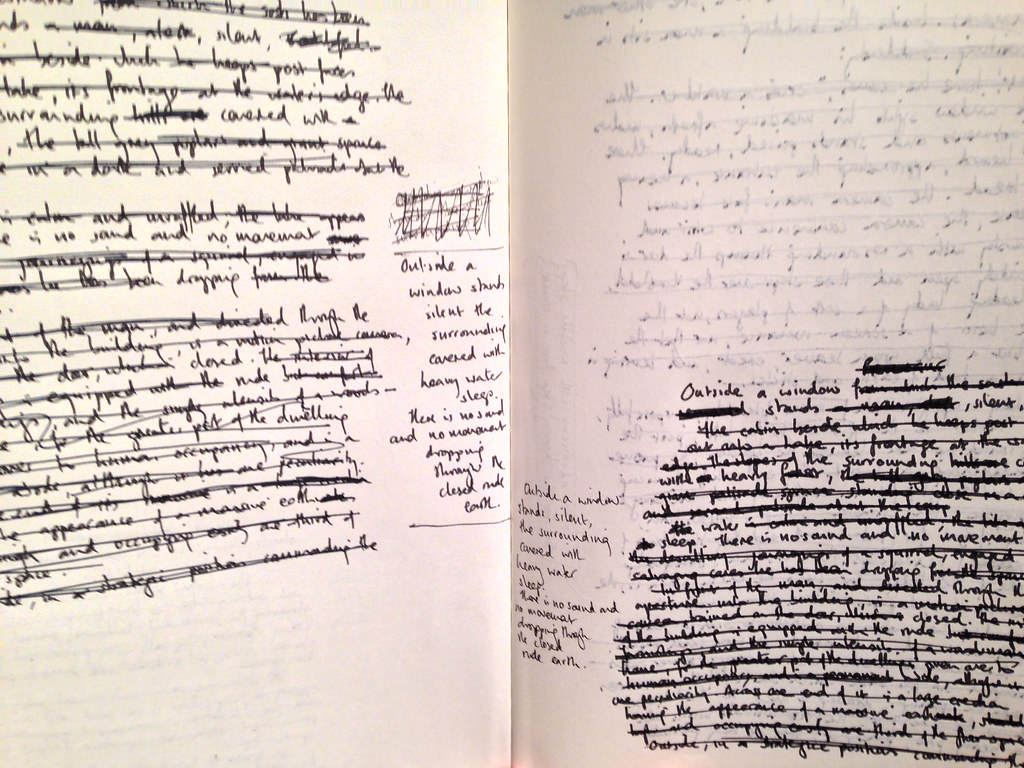

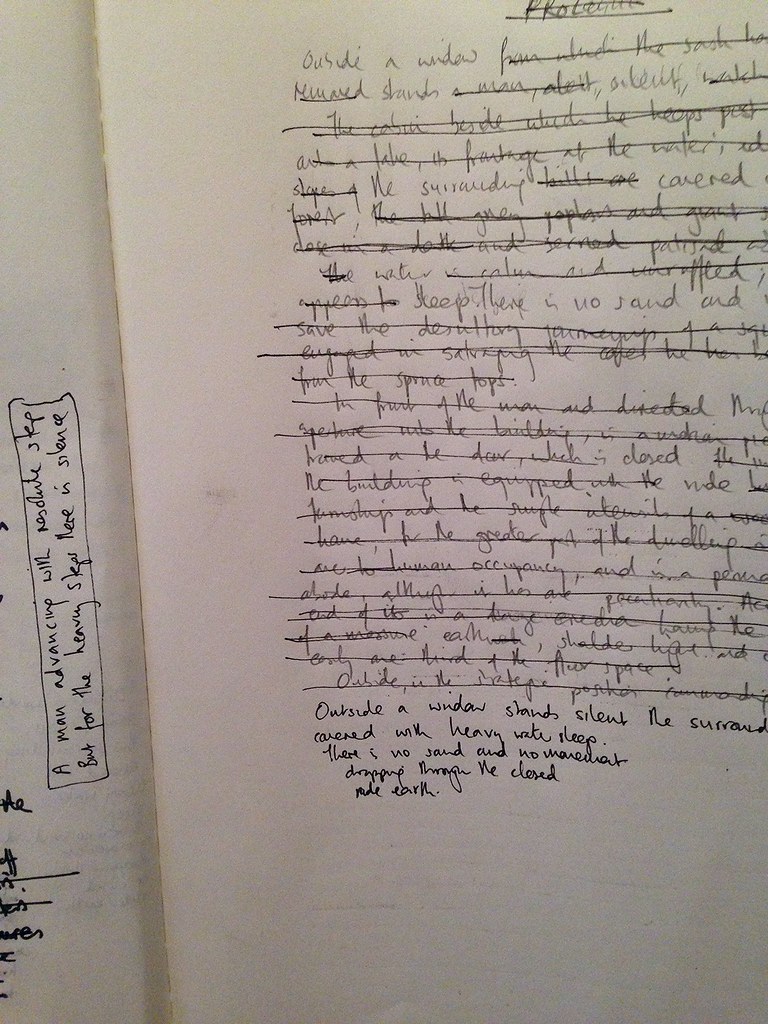

Heavy Water Sleep (Textwork) I

This afternoon I’ve been working on a new approach to my Heavy Water Sleep series. I’ve always loved the aesthetic of the notebook – the crossings out, the marginalia, the sense of time – not only its accumulation through the pages, but its nowness in the moments of writing.

In particular, I love the pages of Walter Benjamin’s notebooks, one of which can be seen below.

A quote from Umberto Eco

“If fictional worlds are so comfortable, why not try to read the actual world as if it were a work of fiction?”

Six Walks in the Fictional Woods

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- …

- 31

- Next Page »