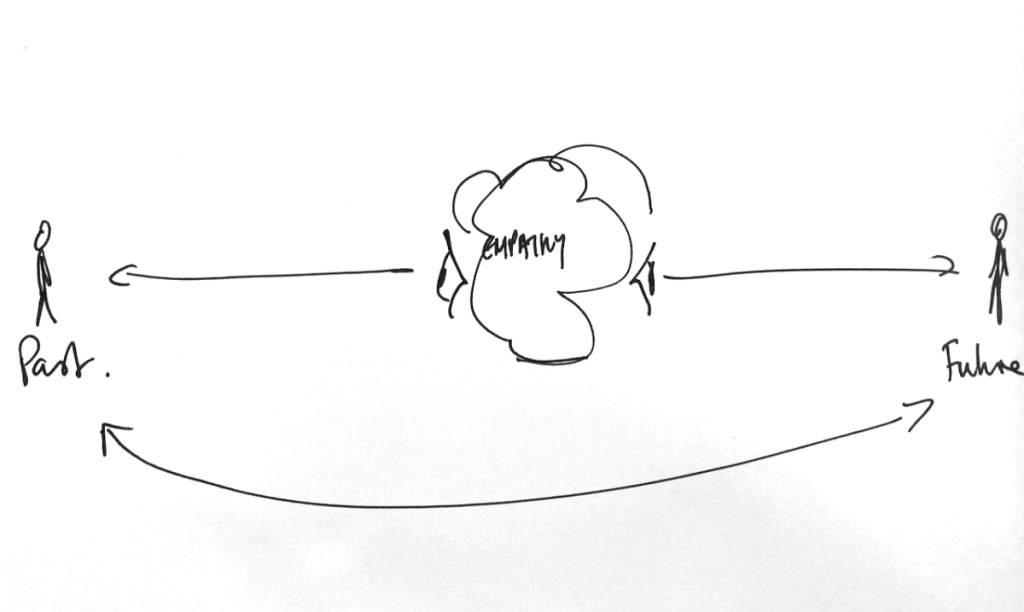

Much of my work over the past however many years has been about empathy and how we can empathise with those who suffered trauma in the past. In part, this line of work began with a visit I made to Auschwitz in 2006 and developed with visits to other sites of historical trauma including the battlefield sites of the First World War.

My work has taken many forms but has often sought to view historical events as if they were taking place now; to understand what it means to be present in the now and apply that back to the past. Now, with the trauma of Climate Change hanging over the world, it’s on the future that my attention is directed.

When I was studying for my MA between 2006-08, Climate Change was a theme explored by several students. But the one thing which struck me was that where the work often sought to educate about Climate Change, it didn’t engage with what I saw as the real issue; action.

Most people know about Climate Change. They know what it is and they know what causes it. Even those who still insist it isn’t a thing know what it is and why it’s happening. The fact they deny it and the fact many people aren’t dealing with it is down to action, or the lack thereof and it’s this that needs addressing. But this won’t be achieved by telling people more and more about Climate Change and what will happen if we don’t do anything.

Looking back at my work over the last 15 years or so, I have tried to engage people with the possibility of directing empathy towards those who no longer exist. I realise now that in order to engage with Climate Change, we need to reflect this view from the past (and those who no longer exist), to the future (to those who haven’t yet been born).

One of the quotes I’ve often used is one from Paul Fussell (see ‘Lamenting Trees‘):

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

Much of my work on historical trauma has dealt with the landscape of war and in many respects, the landscape of the future, if Climate Change isn’t dealt with, will be akin to that of a war. The opposite of war, as Fussell writes, is peace and the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral. If we consider the destruction of the natural world, then this quote becomes even more powerful.

In my novel ‘Brief Castles’, I wrote the following which was based on an experience I had with the painting described.

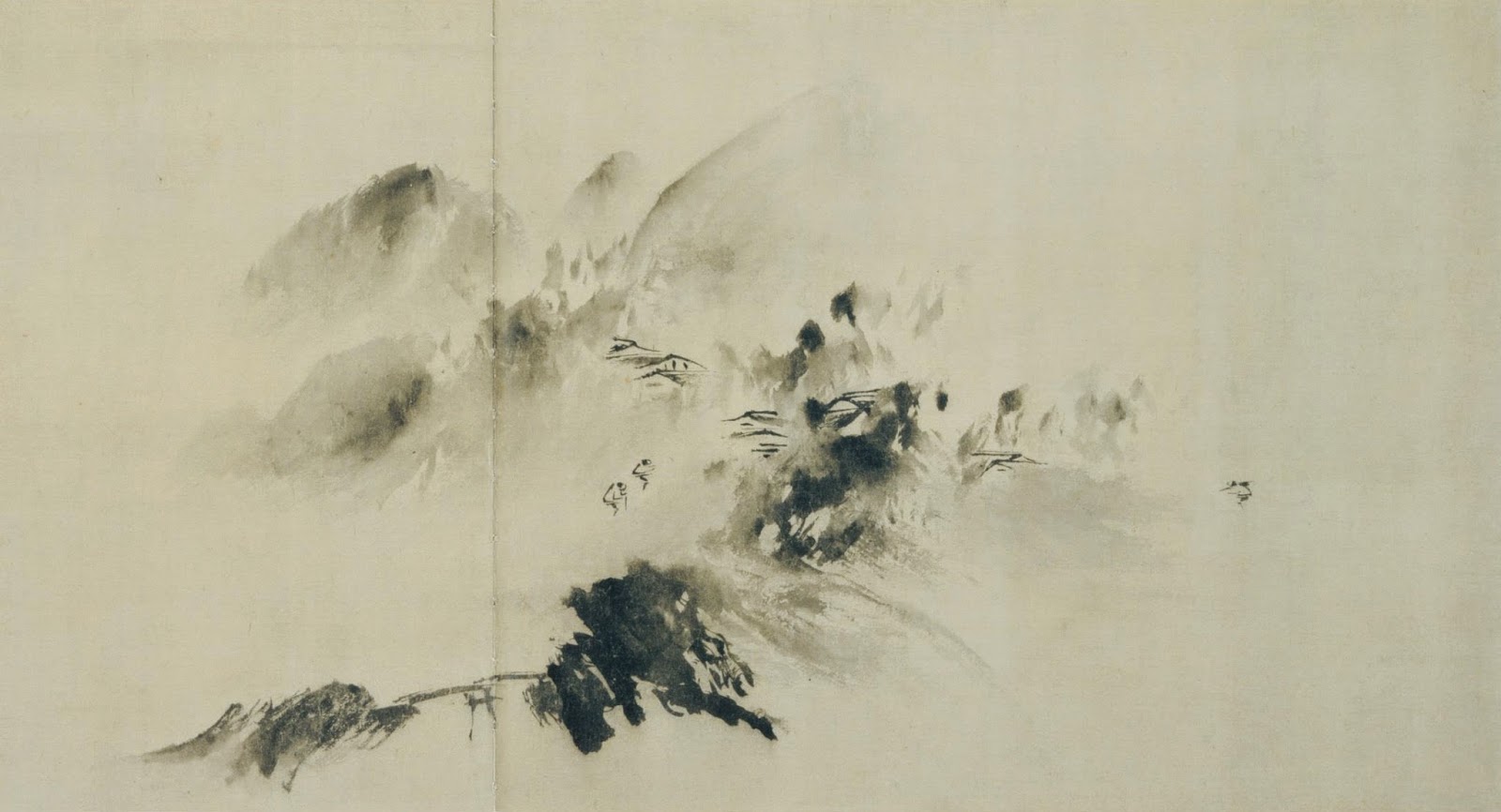

“And as I look, I’m reminded of a painting I once saw in London, during one of my a lunch hour tours of the British Museum. I’d never before considered myself a fan of Chinese art but on this occasion I was quite entranced. Entitled Mountain Village in Clearing Mist by Yu Jian, the painting was made all the more extraordinary on account of its age, made, as it was, around 800 years ago in the mid 13th century. This seemingly rapid work transported me to a time long gone. It revealed – much as with the Japanese haiku of Basho – an ancient and vanished moment, not so much through what it showed but how it was depicted. It was almost as if I could see the landscape before the painter himself. I could see the work as a whole (the landscape as a whole), but then, whilst picking through the gestures of the artist, evident enough in the brushstrokes, I could see the landscape as it was revealed. Yu Jian’s painting was not a painting of what was experienced, but rather the experiencing of what was experienced. It was almost as if the painting had become a painting, not of Yu Jian looking at the mountains, but of the mountain ‘seeing’ Yu Jian. It wasn’t the mountain that was made visible on the paper, but the artist himself – his presence at that moment.

800 years after his death, and Yu Jian was as good as sitting next to me. Or to put it another way, 800 years before I was born, I was as good as sitting next to him.

Death had been defeated.”

There’s a quote I’ve often used from Christopher Tilley. In his book, The Materiality of Stone – Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology, he writes:

“The painter sees the trees and the trees see the painter, not because the trees have eyes, but because the trees affect, move the painter, become part of the painting that would be impossible without their presence. In this sense the trees have agency and are not merely passive objects… The trees ‘see’ the painter in a manner comparable to how a mirror ‘sees’ the painter: that is, the trees like the mirror, let him become visible: they define a point of view on him which renders for him something that would otherwise remain invisible – his outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence… the trees and mirror function as other.”

One of the things which has interested me in my study of historic trauma is the fact that in order to see the past in what was its ‘presentness’ we have to consider our own non-existence. This can, I think, become a barrier to engagement and the same might be true when considering the future. But in the extract above, where the character, Tom, sees how he can mentally defeat his own impending death through a dialogue with an artist’s engagement with nature 800 years before (this ‘other’), we can see that this barrier is easily dissolved. This distinction between humans now and humans then or those to come is broken down; it doesn’t exist. It’s as if our empathy, dammed by these twin obstacles of distant past and distant future, is allowed to flow freely backwards and forwards in time.

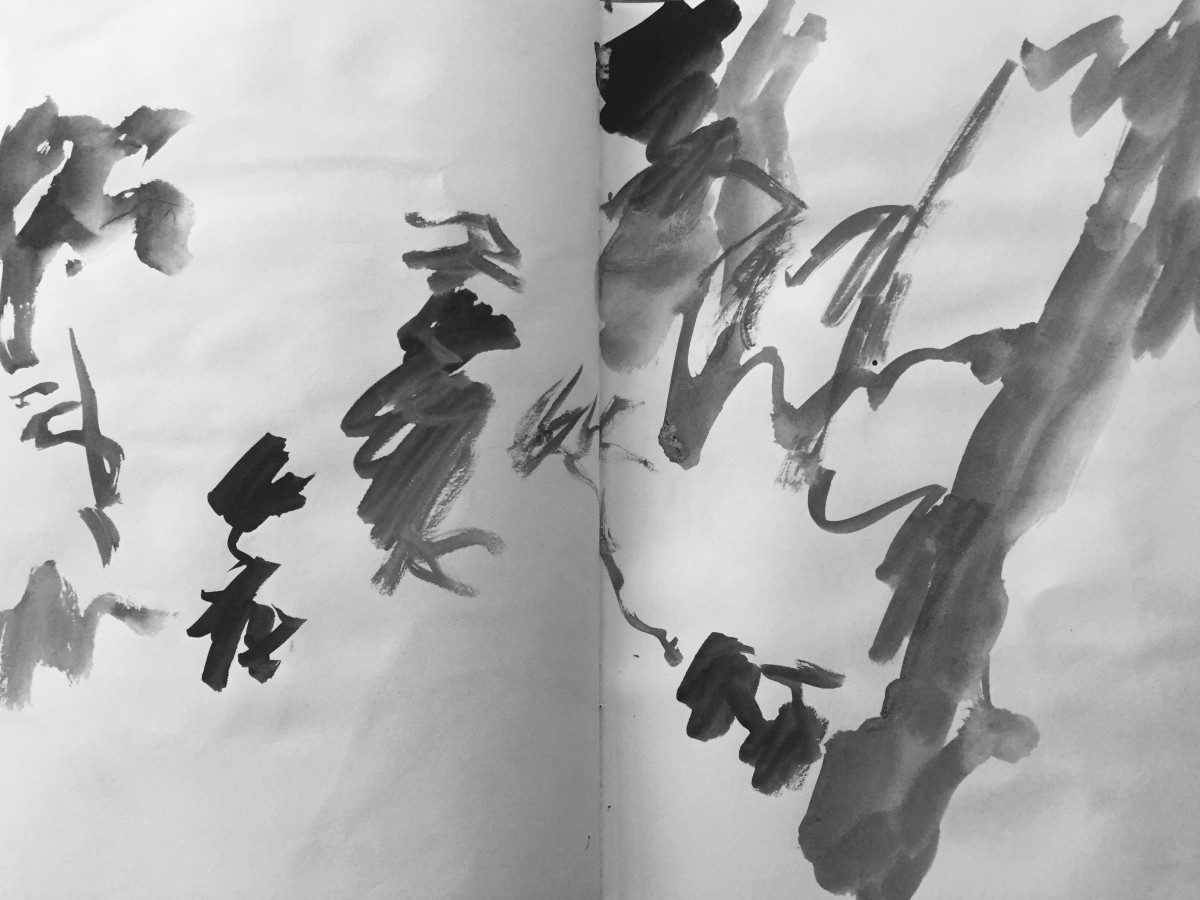

With regards Yu Jian, this breaking down of 800 years of time occurs because of his brushwork – the gestures of the living artist, and these gestures are similar to those in paintings I made in Shotover Wood a few years back whilst tracing the shadows cast by the trees.

The idea behind these and also a video I made of the same patterns was that these paintings – gestures – were all that remained of the wood in that moment. Of course the wood still exists as an entity today, but the wood I experienced at that particular time has gone and in order to rediscover that moment we have to use the gestures of the artist (in this case, me) and the patterns in the paintings or the video to reimagine the woods and that lost moment in time (much as we might reimagine a world from a single object in a museum (for example a pair of mediaeval shoes)).

There is also the fact that these brushstrokes remind me of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy – something I’ve always admired. And just as I cannot read these beautiful texts, so these brushstrokes I made in the wood are like a lost language; one which we need to read in order to understand the world/time from which they came.

Again this links back to Paul Fussell’s quote, where we are asked to propose moments of pastoral in order to experience the opposite of war (while we cannot experience a war we haven’t lived through, we can through proposing moments of pastoral, understand what it would mean to lose those moments and thereby glimpse that war through the absence of that peace). And now, if we think of the future, where that landscape of Climate Change will be a warlike one (one which we cannot experience), we are again proposing moments of pastoral, not to reimagine a time that has past, but a warlike time yet to come, when in actuality, so much of the natural world, woods and forests included, will be lost.