On what was a beautiful Autumn day, I took a walk to Shotover wood to take some photos of trees. I’ve always loved Shotover, both for its place in my past and that of my family, and its own history, being as it once was the main road to London (the mounting steps at the top and bottom of the hill are particularly interesting). The following images are a few of the photographs I took.

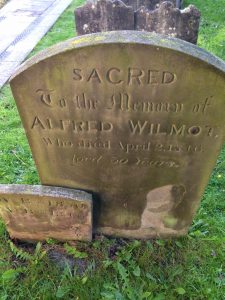

Alfred Wilmot

Having photographed the grave of Henry Sides, I took one of another grave which had caught my eye whilst walking the same path. This belonged to an Alfred Wilmot:

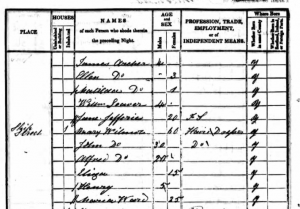

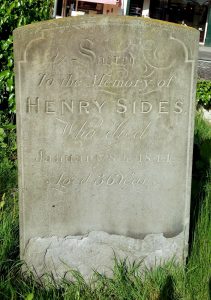

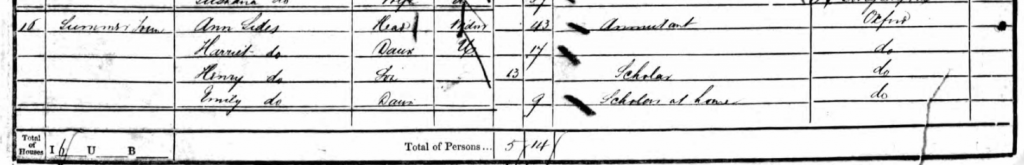

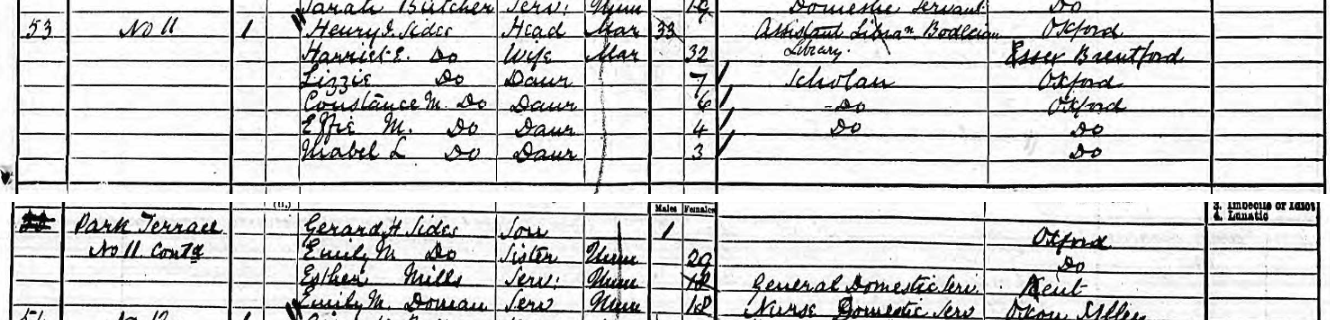

Henry Sides and family

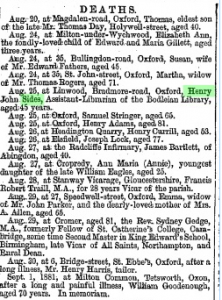

Everyday, on my way to catch the bus after work, I pass by this grave at the edge of the path which cuts through St Giles churchyard.

Ten years on, in 1881, Henry and Harriet have extended their family still further, with the arrivals of Arthur, Herbert, Gertrude and Archibald. They had moved too, living now in Bradmore Road with a Cook and a Nursemaid. At 42, Henry is still an assistant librarian and partner in a firm of rope makers.

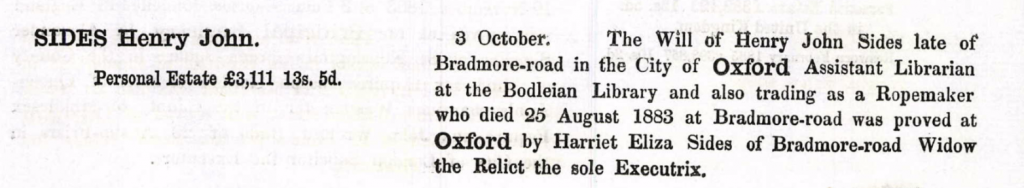

Henry John Sides died on 25th August 1883, aged just 45…

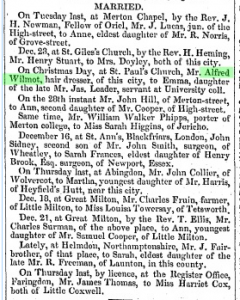

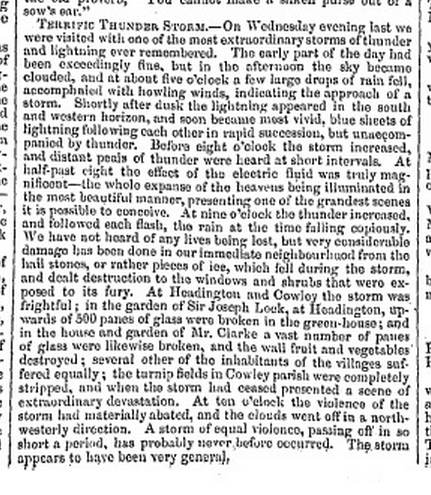

A Victorian Storm

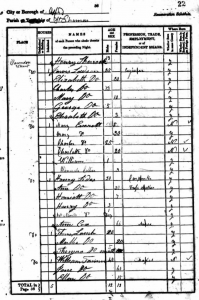

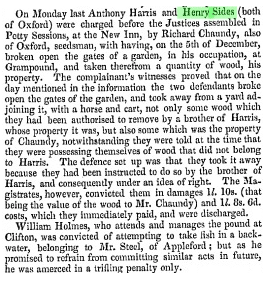

Whilst researching Jackson’s Oxford Journal, I randomly selected an edition from 1842 in which I found the following:

Following on from my last blog and my interest in the perception of time in the past as time passing I’m drawn to this piece which serves, I think, to illustrate the point.

For example, the first line:

“On Wednesday evening last we were visited with one of the most extraordinary storms of thunder and lightning ever remembered.”

Firstly, the words “Wednesday evening last,” pinpoints the storm in terms that are not ‘historical’. It’s not as if we’ve read in a book, “on September 7th 1842, a great storm hit the city.” Rather the event is located in time using a phrase we might use today. It locates the storm in relation to the present – even if that present is September 10th 1842 – and at once feels fresh and contemporary.

Secondly, the phrase “ever remembered,” reminds us, if you pardon the truism, that there was a time before this time. But whereas we know that before 1842 there was 1841 and so on, what this phrase describes is living memory. Again, if we were reading about the storm in terms of its being an historical one, we would know that everyone who experienced it was dead. Reading this article, they are very much alive. Not only that, but the whole of the nineteenth century – and perhaps a part of the eighteen is alive within them too.

It isn’t only this storm which lives within these words, but many others stretching back as far as the late 1700s.

The next description is something with which we have all experienced:

“Shortly after dusk, the lightning appeared in the south and western horizon, and soon became most vivid, blue sheets of lightning following each other in rapid succession, but unaccompanied by thunder.”

That lack of thunder is the punctum of this text. (Ironically, the last time I mentioned punctum in a blog was in an entry entitled ‘Silence‘ about the death of my great-great-uncle, Jonah Rogers.) All the sounds of Victorian Oxford, on that September night in 1842 are contained in that silence. Even within our imaginations, it would seem that the the absence of one sense, heightens all the others. We can sense the approaching storm, feel its presence on the horizon. We can see the muted colours of dusk, muted further still.

Then the thunder comes – “distant peals of thunder” as the writer puts it – which increase until by 9 o’clock, it accompanies every flash. This means of course that the storm was right above the city. The rain falls hard, and with it hail – or “pieces of ice,” which damage numerous properties and the turnip fields of Cowley. By 10 o’clock it was over.

One of the names mentioned in the piece is Sir Joseph Lock whose greenhouse was damaged to the tune of 500 panes of glass. An unpopular man, he built Bury Knowle House in 1800 (the gardens of which feature in another recent blog). Here in Headington, as it was in Cowley, the storm “was frightful” and we can imagine Mr Lock looking out the window of his house as the storm lashed his garden, his face, in the dark midsts of the past, illuminated for a moment by the lightning.

Fields of East Oxford

The following is taken from my Blog and is reproduced here as it refers to research concerning East Oxford, and in particular the area surrounding the road up which the ‘Gentleman’s Servant’ would have ridden:

I’ve spent a very interesting morning in the archives at Christ Church college, researching as part of the East Oxford Archaeology Project. I had no fixed idea as to what I wanted to look for but was interested to see where the various material on offer would lead me.

I started by looking at a large and beautiful map of 1777 which showed the field system in East Oxford along with the names of fields and some of the individual furlongs. The abundance of units of measurement are quite baffling but nonetheless very poetic: furlongs, perches, chains, rods etc. and the way locations of land are described equally interesting; for example “The field called the Lakes begins next to Drove Acre Meer shooting onto the Marsh.”

A meer as far as I’ve been able to ascertain is a boundary deriving from the Old English world mǣre. Interestingly, Drove Acre still exists today in the form of Drove Acre Road, which joins with Ridgefield Road, so named after the old Ridge Field on which it’s built. Before I go into other field names, I want to try and identify the different units of measurement.

A rood is a unit describing an area of land and is equivalent to 1/4 acre. An acre is therefore 4 roods. In terms of length, an acre is a furlong (a furrowlong) which is equivalent to 10 chains or 220 yards. A chain therefore is 22 yards. A rod, pole or perch is 5 1/2 yards. A mile is 8 furlongs.

I also found a unit called a butt, which I believe is where the oxen (ploughing a furlong) turned and rested where one acre butted onto the next creating a small mound of earth.

The names of the main fields in this area – as I discovered in a document of 1814 – are as follows:

Bartholomew Field

Ridge Field

Compass Field

The Lakes

Broad Field

Church Field

Far Field

Wood Field

Open Field Meadow

The name Far Field makes sense in that it’s situated some way from town. But The Lakes?

Within these fields, individual furlongs were also given names, such as:

Pressmore Furlong

London Way Furlong

Ridge Furlong

Furlong by the Mead Hedge

Clay Pits Furlong

Furlong Shooting on Breaden Hill

Short Furlong in Catwell

Brook Furlong

Hare Hedge Furlong

Croft Furlong by Bullingdon Green

The word shoot or shooting is used a lot to describe the location of land, such as ‘Furlong shooting on Sander’s Marsh.’ I think this must mean that the furlong joins or abuts the marsh. ‘The furlong that shoots on the alms-house,’ for example seems to describe land that joins the alms-house which I think describes those in St. Clements.

What interests me is how differently this area of Oxford would have been known to those who lived 200 years ago. It’s an obvious point given that much of what were fields are now houses, but it’s the names that interest. How did these places acquire these names, and why have some survived and others haven’t? (It’s probably just as well that no-one lives in Shittern Corner today).

Fields

I’ve spent a very interesting morning in the archives at Christ Church college, researching as part of the East Oxford Archaeology Project. I had no fixed idea as to what I wanted to look for but was interested to see where the various material on offer would lead me.

I started by looking at a large and beautiful map of 1777 which showed the field system in East Oxford along with the names of fields and some of the individual furlongs. The abundance of units of measurement are quite baffling but nonetheless very poetic: furlongs, perches, chains, rods etc. and the way locations of land are described equally interesting; for example “The field called the Lakes begins next to Drove Acre Meer shooting onto the Marsh.”

A meer as far as I’ve been able to ascertain is a boundary deriving from the Old English world mǣre. Interestingly, Drove Acre still exists today in the form of Drove Acre Road, which joins with Ridgefield Road, so named after the old Ridge Field on which it’s built. Before I go into other field names, I want to try and identify the different units of measurement.

A rood is a unit describing an area of land and is equivalent to 1/4 acre. An acre is therefore 4 roods. In terms of length, an acre is a furlong (a furrowlong) which is equivalent to 10 chains or 220 yards. A chain therefore is 22 yards. A rod, pole or perch is 5 1/2 yards. A mile is 8 furlongs.

I also found a unit called a butt, which I believe is where the oxen (ploughing a furlong) turned and rested where one acre butted onto the next creating a small mound of earth.

The names of the main fields in this area – as I discovered in a document of 1814 – are as follows:

Bartholomew Field

Ridge Field

Compass Field

The Lakes

Broad Field

Church Field

Far Field

Wood Field

Open Field Meadow

The name Far Field makes sense in that it’s situated some way from town. But The Lakes?

Within these fields, individual furlongs were also given names, such as:

Pressmore Furlong

London Way Furlong

Ridge Furlong

Furlong by the Mead Hedge

Clay Pits Furlong

Furlong Shooting on Breaden Hill

Short Furlong in Catwell

Brook Furlong

Hare Hedge Furlong

Croft Furlong by Bullingdon Green

The word shoot or shooting is used a lot to describe the location of land, such as ‘Furlong shooting on Sander’s Marsh.’ I think this must mean that the furlong joins or abuts the marsh. ‘The furlong that shoots on the alms-house,’ for example seems to describe land that joins the alms-house which I think describes those in St. Clements.

What interests me is how differently this area of Oxford would have been known to those who lived 200 years ago. It’s an obvious point given that much of what were fields are now houses, but it’s the names that interest. How did these places acquire these names, and why have some survived and others haven’t? (It’s probably just as well that no-one lives in Shittern Corner today).

Ghosts of the Church of St. Clement

The old church of St. Clement, built around 1122 is a principal character in our story. It was described by the antiquary Thomas Hearne as “a very pretty little church,” but unable to serve the growing population of the parish, it was demolished in 1828 and a new church built on Hacklingcroft Meadow in Marston. The church’s three bells (one of which is the oldest bell in Oxford, dating to the 13th century) were taken to the new building. The church’s graveyard remained until 1950, when it too disappeared with the construction of The Plain roundabout.

The toll house in front of the tower remained until the construction of the Victoria Fountain in 1899. The photograph below, taken in 1868, shows the old toll house and the churchyard behind.

Looking closely one can see the gravestones…

…and the ghosts of those who walked too fast.

It’s interesting to compare the image above with the text of the newspaper notice. Both contain the likeness of a man on the same stretch of road, and yet that created 100 years earlier with words is, somehow, all the more clear. With the image above, we feel the same sensation as when we look at other very old photographs; a kind of vertigo which links – through a ‘carnal light’ – two poles of simultaneous existence and non-existence. We look at the image of a man in a time when he doesn’t exist, while he looks back from a time when we have yet to be born. Here we both are, and aren’t at the same time. The light, captured in the image, is, like an “umbilical cord” which as Sontag says, “links the body of the photographed thing to my gaze – light though impalpable, is here a carnal medium, a skin I share with anyone who has been photographed.”

In truth, we share this skin with anyone who’s ever been and it’s through our bodies that we identify with those who’ve gone before us. With the text, our sense of the man comes not only through that which the words describe, but through the questions it asks and leaves unanswered. Furthermore, there is a sense of movement in the writing. We not only get a snapshot, but a full few minutes of this anonymous man’s life – a seemingly insignificant moment which serves, ironically, to make him all the more clear. It’s as if the blurs in the photograph above, caused by the long exposure and the movement of those in view, were instead a piece of film, one in which we don’t see a ghost, but a living, breathing individual.

This sense of movement is of course something we also share, and it’s this kinaesthetic aspect of the text which seems to count the man – whose more than likely been dead for more than two centuries – among us. Because I’ve walked and experienced the insignificant, ‘everydayness’ of moments on the bridge, I seem to know him better than, for example, I do the man who stands against the toll house in the photograph. The man and the toll house have both disappeared. But the line of movement, the narrative line, and therefore the stranger of our tale, persists to this day.

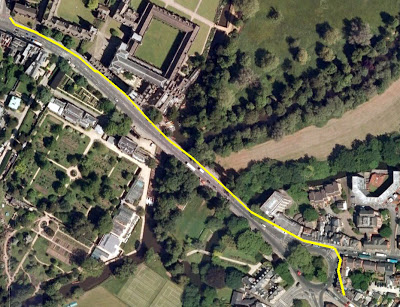

The Narrative Line

With my GPS, I traced the route we know the Gentleman’s Servant took across Magdalen Bridge up into modern day Cowley Road. It was hard to imagine the scene in 1770 when the road would have been much quieter. Cars, buses and motorbikes were everywhere, the sound of their engines blocking out almost everything else.

But nevertheless, as I walked, I tried to take in everything around me, to capture all that made the present moment what it was, for even though the same place in 2010 is light years away from what it was 240 years ago, nevertheless, when the stranger rode over the bridge on December 12th 1770, it was something which for him was happening in the present. Now this might sound an obvious thing to say, but often when we read about the past, it’s almost as if we’re reading a fiction – a story which has a beginning, a middle and an end, and in which the characters follow a proscribed route laid down by the author: the narrative line in this instance comprises the text which makes up the tale. Of course life isn’t like this. When we walk, even if we’re going somewhere particular, we walk without knowing what may lie ahead of us. We might well know where we’re going, but how we’ll get there exactly, and what will happen as we travel, is something we only discover in the present moment.

As I wrote as part of a recent exhibition:

The Past is Time without a ticking clock. A place where paths and roads are measured in years. The Present is a place where the clock ticks but always only for a second. Where, upon those same paths and roads we continue, for that second, with our existence.

I want to read history in terms of its seconds – the small spaces within which life really happens. Every second in the present day – every moment – is a lens through which we can glimpse the past, no matter how distant it is. The more we know about the past (in particular the ‘geography’ of whatever we’re researching) the better the picture. But something in the space of every second reminds us, that what happened in the past happened in what was then a present just like ours; something as a simple, for example, as trees blowing in the wind.

The narrative line is like a piece of text; we follow it as we follow the words of a sentence, putting one foot in front of the other. But reading between the lines, we fill the gaps with what we see and experience around us. We are reminded that the stranger was moving all those years ago, unaware of what might lay before him. We become aware that he could feel the wind on his face, that he could see the sky, the river flowing beneath the bridge. And as we think, we realise that he himself was thinking, as was everyone around him – and this is the key to answering the questions I posed at the beginning of this project.

Every second the stranger rode along that line, he was part of a complex web of connections. These moments comprising his story were moments in many others – countless stories in a plot more complex that we can imagine. The more we know about these moments, the more we can picture the scene and all who lived at the time, the better the chance we have of finding answers.

As I walked the length of the line, I looked to my right and glimpsed the 17th century gateway to the Botanic Gardens, and in that gesture, I found a connection with the stranger. The gateway is a witness to the moment I’m researching, and looking at it is one way of asking it for an answer.

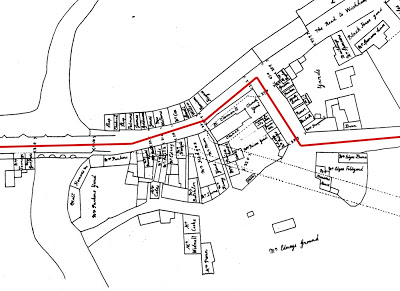

John Gwynn’s Survey 1772 – Pt 2

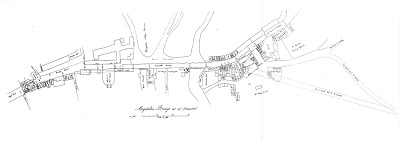

Whilst looking through some old research I did a few years ago, I came across the drawing reproduced below of Magdalen Bridge and its environs taken from John Gwynn’s survey of 1772.

It shows the route we know the stranger took – the narrative line of this story – on December 12th 1770 along with the names of those who lived or owned properties bordering the street in 1771/72. Interestingly, my namesake – at least as far as my surname goes – owned property just in front of the old church of St. Clement which was demolished in 1828.

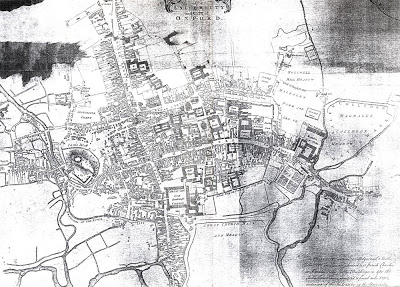

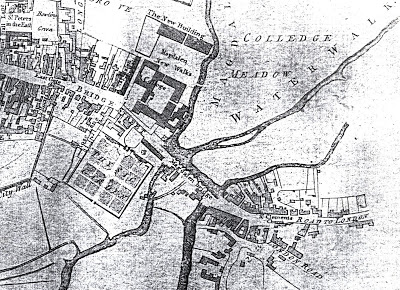

Map of Oxford 1750

Although this map was made 20 years before the time which I’m researching, it gives nonetheless a good idea as to what the town looked like before the Mileways Act of 1771.

Magadalen Bridge is on the right hand side of the map, a detail of which can be found below.

The Gentleman’s Servant would have taken what’s described as the London Road at the bottom of the image.

John Malchair (1730-1812)

I first encountered the work of John Malchair in 1998, at an exhibition in the Ashmolean Museum Oxford. Being as I am from Oxford, I was immediately struck by the beauty of his drawings which revealed through their own delicate rendering, the fragility of vanished places in and around the city.

According to Colin Harrison in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition, John Malchair was ‘the most important and influential drawing master in eighteenth century Oxford’. He was a German violinist who for over thirty years supplemented his earnings as leader of the band at the Holywell Music Room.

The following abridged text is taken from the catalogue; Malchair the Artist by Colin Harrison.

“He was baptised on 15th January 1730, in St. Peter’s Church, Cologne, the eldest son of a watchmaker, Joannes Malchair and Elizabetha Rogeri. They lived together in Sternen Grasse in a house next door to that where the Rubens family spent a difficult period between 1578 and 1587. After leaving his native city, he moved to Nancy and in 1754 arrived in England. Apart from short tours of Wales in his retirement, he never left his country of adoption.

After making his first appearance at the Three Choirs Festival in September 1759, where he was to play annually until 1776, Malchair came to Oxford to compete for the position of leader of the band at the Music Room after the death of Thomas Jackson. He won the competition and made his first appearance at the Widow Jackson’s benefit on 29th November or the choral concert on 12th December.

When Malchair arrived at Oxford, the city was essentially contained within the mediaeval city walls. As the first guidebook to the city – ‘A Gentleman of Oxford, The New Oxford Guide’ published in 1759 describes:

‘The town rises on a broad eminence which arises so gradually as to be hardly perceptible, in the midst of a beautiful extent of meadows, to the south, east and west and cornfields to the north. The vales on the east are watered by the river Cherwell and those on the west and south by the main stream and several branches of the Isis. Both rivers meet towards the north-east. The landscape is bounded on every side, the north excepted by a range of hills covered with woods….’

Walking was a popular pastime in such pleasant surroundings, in the streets, college gardens and father afield to nearby villages, such as Headington in the east, with its magnificent views from Shotover Hill.

Malchair quickly settled into the rhythm of rehearsals and concerts required at the Music Room and took his first pupils for drawing soon after he arrived. In 1760 he married Elizabeth Jenner who died ‘after a lingering illness’ on 14th August 1773. Malchair was deeply affected, and in later years frequently thought of their happy years together.

He died in 1812 and was buried in St. Michael’s church on 19th December 1812.”

In ‘Malchair the Musician’ also in the catalogue, Susan Wollenberg describes how Malchair “developed the idea of collecting tunes ‘on location'”.

“Interspersed with the many items from Playford and other published sources were his own discoveries. Numerous annotations to melodies in the collections… show Malchair’s eagerness in this regard. Beyond the academic and the musical aspects of his work are the pure ‘collector’s instinct’ and delight in acquisition. As Malchair remarked in his vivid English, ‘the leasure howers of many years were employed in forming this collection, ney, necessary busness was at time incrotched uppon when the fitt of collecting Grew Violent.”

Crotch (William Crotch, who, as a ‘Child in a Frock on his Mother’s Knee, performed the organ in the Music Room, to the great astonishment of a large audience’, on 3rd July 1779 – aged three) describes how No.156 of his Specimens was ‘written down by Mr. Malchair, who heard it sung in Harlech Castle’. Malchair himself notes that his version of ‘The Grand Duke of Tuscany’s March’ is ‘as played by a Savoyard on a barrill Organ in the Streets at Oxford. November 30 1784’.

The streets of Oxford were evidently a fertile source. Among the items gathered in the Cecil Sharpe House volume they yielded, besides the March already mentioned, such gems as La Rochelle, ‘played by a Piedmontese Girl on a Cymbal in Oxford Streets December 22 1784’ (and recorded together with Malchair’s instructions for reproducing the effect on the violin); an untitled tune resembling ‘Early One Morning’ transcribed ‘from the Singing of a Poor Woman and two femal [sic] Children Oxford May 18 1784’; a topical item, ‘The Budget for 1785. Sung in the Streete July 21 – 1785 – Oxon A Political Balad on Mr Pit’s Taxes,’ a tune for flute a bec [recorder] and Tambour’ which Malchair heard ‘play’d in the Streets at Oxford Ash Wednesday Feb: 25 1789’; and, most evocatively, the lively ‘Magpie Lane’ tune: ‘I heard a Man whistle this tune in Magpey Lane Oxon Dbr 22 1789. came home and noted it down directly.”

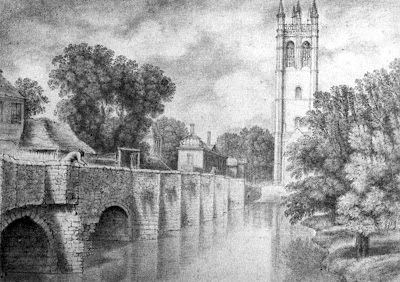

Magdalen Bridge c.1772

The image below is a drawing of Magdalen Bridge made around 1772 by the German artist John Malchair. Following the passing of the Mileways Act in 1771, Malchair made a number of studies of the old bridge so as to record it for posterity.

With various parts of the mediaeval city threatened because of the Act, Malchair drew a number of views of buildings and structures including the North Gate and Bocardo Prison and Friar Bacon’s study which eventually fell in 1779.

This then is the bridge over which The Gentleman’s Servant crossed with two horses on December 12th 1770.

Annotations (Deadman’s Walk)

A bastion of the old city wall, Deadman’s Walk, 1907

© Oxfordshire County Council

The same bastion today.

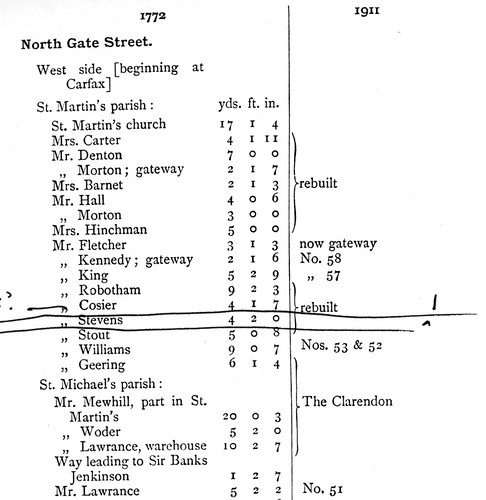

John Gwynn’s Survey 1772

Remarkable evidence of those who lived in Oxford around the time the notice appeared in Jackson’s Oxford Journal can be found in a survey carried out by John Gwynn in 1772 (John Gwynn also designed the new Magdalen Bridge). Made as part of continuing improvements originating with the Mileways Act of 1771, the actions of Gwynn (who could be seen around town measuring the fronts of houses and other buildings) aroused suspicion and even alarm among the city’s residents. The survey itself was required to calculate the costs of repaving the city’s streets for which each property was liable to pay a share depending on the size of their facades. What we have as a result is a wonderful record; a long list of names of all the city’s residents (or rather property owners), the streets on which they lived (or owned property) and the size of their dwellings – given in yards, feet and inches. It’s interesting for me that among the many Stevenses listed in the survey might well be my great-great-great-great-great-grandparents.

The page reproduced below, is taken from the survey and represents the bottom end of the High Street where it meets Magdalen Bridge – the Bridge can be seen listed below the name of a Dr. Sibthorpe. The Physick Garden above, is the old name for what is now the Botanic Gardens.

See also John Gwynn’s Survey 1772 – Part 2.

Magdalen Bridge 2010

Although the present bridge is not that over which the enigmatic stranger crossed, it nonetheless marks the line he travelled and along that line are witnesses to the moment I’m researching. Below are a few photographs which I took today showing the famous landmark.

Magdalen Tower (above), as seen from the east, was completed in 1509 and would have seen the stranger pass below on his way over the bridge towards what was then the Watlington Road. The image below shows the route he would have taken with his two horses, from Magdalen Bridge on the right of the picture, towards what is now The Plain, but which in the stranger’s day would have been the church and churchyard of St. Clement, demolished in 1828.

The roundabout (below) stands on what was once the church and churchyard of St. Clement . To the right is the fountain, built in 1899 as a belated tribute to Queen Victoria who celebrated her Diamond Jubilee in 1897. This was built on the site of the old toll house. The houses in the background stand on modern-day Cowley Road, the road up which the stranger rode into obscurity.

As I walked up the bridge I wondered who had seen the stranger pass and where they’d been when they saw him riding the two horses. In terms of more witnesses, the walls of the Botanic Gardens (founded in 1621) and its gateway (built by Inigo Jones’ master-mason Nicholas Stone in 1632) would have been standing at the time. The two statues and the bust, positioned in the gateway still look towards the road…

…and I like to imagine their eyes would somehow have seen him.

Magdalen Bridge

The bridge over which our Gentleman’s Servant rode in December 1770 is not the same bridge which crosses the River Cherwell today. Being as it is an important part of the story, I’ve copied an entry on the bridge from The Encyclopaedia of Oxford1 which I’ve reproduced below.

A bridge, formerly known as Pettypont and East Bridge, has stood here since at least 1004. In the Middle Ages the cost of its upkeep was shared between the county and the town, the town meeting its three-quarters share largely by alms and charitable bequests, the maintenance of bridges being then considered a pious duty. Bridge-hermits were also appointed to help travellers with any difficulties they might experience in crossing. The original bridge was of wood, but by the 16th century a stone bridge, some 500 feet long, with about twenty pointed and rounded arches, had been constructed.

At this time the city was still paying for repairs, both by taxation and by the allocation of alms; but William of Waynflete, the founder of Magdalen College, may have paid for restoration of the bridge in the 15th century, and the University certainly did so in 1723. Although a major restoration was then undertaken, less than fifty years later some of the piers had been swept away by floods and the western end had collapsed completely. Condemned as dangerous, it was rebuilt between 1772 and 1778 under the provisions of the Oxford Improvement Act of 1771, to the design of John Gwynn. At the same time a toll-house was built at The Plain, with gates across the roads from Headington to Cowley to collect dues for the maintenance of the bridge. Twenty-seven feet wide, with recesses in the middle, the bridge’s large semi-circular arches were supplemented by smaller ones over the towpaths. The plain balustrade was designed by John Townesend after plans for a more elaborate one had been dropped. The bridge was widened in 1835 and again in 1882. Notabilities have frequently been welcomed or taken their official departure at the bridge, as Queen Elizabeth I did on leaving Oxford in 1566.

1 The Encyclpaedia of Oxford, 1988, Ed. Christopher Hibbert, Assoc. Ed. Edward Hibbert; London, Macmillan London Limited

Echo

Last week I installed a temporary artwork in St. Giles, Oxford entitled Echo. The piece comprised approximately 200 photographs of individuals isolated from group shots of the fair taken in 1908, 1913 and 1914. The date of the exhibition, Wednesday 9th September was important in that it was the day after St. Giles’ Fair was taken down, and the ‘space’ left in its wake (the fair was up for two days and filled the entire street) helped frame the fact that all those people shown in the exhibition, who had once stood in the same street, had, like the fair, gone. I was interested in the boundary between existence and non-existence, the impossiblity – within the human mind – of death as nothing and forever. What I hoped the photographs conveyed was the importance of having been.

The installation required grass in order that I could place the markers in the ground and the War Memorial in St. Giles was the only viable option. What was particularly interesting was how the location altered the meaning of the work in that one couldn’t help identify the people with the memorial and in particular those who fell in World War One. Given that some of the men pictured in the photographs almost certainly went to war and may well have lost their lives, so the work took on a new and poignant dimension. Many of the women would have lost husbands, brothers, fathers, uncles and so on.

Click here to read more about this exhibition.

Same People

Having bought a copy of a photograph (St. Giles Fair, 1913) from the Oxfordshire County archives, I found when looking at the individual faces someone I recognised. Not someone I know or knew of course, but a lady I’d seen in another photograph.

The photograph on the left was taken on Headington Hill in 1903, and that on the right at St. Giles Fair in 1913. Below is another person I found in two different photographs, this time from 1908.

Mr Stevens

A year or so ago, I started work on a piece of work based around John Gwynn’s survey of 1772. The piece was called (as a working title) ‘6 Yards 0 Feet 6 inches’ based on the measurement of John Malchair‘s home in Broad Street. Having discovered an ancestor – John Stevens – born in the city in 1811, I wondered if there was any chance that one of the Mr Stevens’ listed on the survey was an ancestor of mine? It seemed a long shot but after today’s research I’m rather more optimistic.

If I did have an ancestor in Oxford at the time of the survey and if my research is correct, then that ancestor would be John Steven, the grandfather of the one previously mentioned. I’ve no idea when he was born but I do know that he was married in 1764 and is described as coming from St. Martin’s Parish, where his son Samuel, John Jr’s father was baptised in 1776. One could assume therefore that I did indeed have ancestors living in the parish of St. Martin’s at the time of the survey.

The images below are taken from the survey and show two Stevens one of which might well be my ancestor.

Gwynn fails to include (at least on the copy I have) first names from the survey but within the parish of St Martin’s two Mr Stevens are recorded along with a Mrs Stevens. One can assume however, that those most likely to be mine are the two Mr Stevens mentioned as living in the parish, one in Butcherrow (now Queen Street), the other in North Gate Street (now Cornmarket). The residence in Butcherrow is 7 yards 0 feet and 6 inches. That in North Gate Street is 4 yards 2 feet 0 inches.

Of course more work is required to see if one of these is indeed my ancestor, but I must admit to being very inspired by the prospect.

Old Newspapers

I’ve just spent the afternoon in the library reading through a selection of old newspapers from 1771/2 along with numerous copies from the ninetheenth century. I was hoping, initially, to find anything mentioning a Mr. Stevens, Tailor as in a survey of the city (1772) made by John Gwynn several Stevens are listed. As my ‘several-greats’ Grandfather was born in Oxford in 1811 and was a tailor, I wondered whether one of these might be a relation. Anyway, unsurprisingly I found no such mention, but what I did find were a few tantalising glimpses into the 18th century city.

The first is the theft of some lead on October 11th 1771:

“Whereas a considerable quantity of lead has been stolen from off the gate of the physic gardens’ opening into Rose Lane. This notice is given that whosoever will give information to the Rev.Dr. Wetherell, Vice Chancellor, so that the offender or offenders may be brought to justice, shall upon his or their conviction, receive a reward of five guineas.”

Whether or not the guilt party were ever brought to book I don’t know. A couple of weeks later, another audacious theft occurred, this time in Holywell Street:

“Whereas on Monday the 21st of this instant October 1771, the iron rails to the steps of Mrs. Wise’s house in Holywell were taken away. This is to give notice that if any one will discover the offender or offenders so that they may be brought to justice, shall, on his or their conviction receive half a guinea reward from Francis Kibblewhite in Holywell.”

Looking at my 1772 survey, I see that Mrs. Wise lived at what is now called No.2 Holywell Street. Mr Kibblewhite lived at what is now No.38.

Following a burglary on November 8th 1771 in Old Butcher Row (modern day Queen Street) the reward offered for information was much more tempting – provided of course, one had information with which to complete any deal, and thus be tempted to impart.

“Whereas the dwelling of Mr. John Greenway situate in the Old Butcher Row, in this city was last night broke open and divers sums of money and other valuable effects stolen thereout. Notice is hereby given that if any person or persons will discover the offender or offenders so that he, she or they may thereof be committed, he shall receive the sum of fifty guineas from me.”

This very large amount of money (a guinea was equal to £1 1s) was offered by Francis Greenway. The following week on November 16th, the news appeared again with an addendum:

“N.B. It is discovered that a plain round gold snuff box and eight gold rings, chiefly Mourning ones belonging to the family were at the same time taken away.”

The following week this appears, just below the same story repeated for the third week and addressed ‘To the Publick’:

“Whereas some evil designing persons have maliciously propagated various infamous aspersions which tend to injure our characters relating to the late robbery committed at Mr. John Greenway’s home in old Butcher Row; in order to vindicate and clear ourselves of the said aspersions, we did severally make oath that we were not in any wise directly or indirectly concerned in the said robbery or have any knowledge of the person or persons who committed the same, and we do declare that the said aspersions so far as they tend to lessen or injure our reputations and characters are totally false.”

The letter is signed again by Francis Greenway although whether he is including himself as one of the aggrieved I’m not sure. Below his name are the names of two servants, Mary Staunton and Jane Carpenter who made their oath before the Mayor, John Austin. Francis Greenway offered a further 5 guineas to whosoever gave information leading to the conviction of the slanderers which he increased to 20 guineas later on. This was not the end however. On December 7th 1771 when the same story appeared with the same letter to the publick beneath, Francis Greenway wrote:

“And as it is apprehended more than one person must have been concerned in the above burglary, this further notice is given that any one giving information against his accomplice or accomplices shall be paid the above reward of 50 guineas upon his, her or their conviction and will likewise, upon being admitted evidence, be entitled to a Free Pardon.”

That was still not the end of the matter. On December 21st, he added that the reward of 50 guineas was “besides the forty pounds allowed by parliament for me.”

These notices or stories were printed every week and did not stop being printed until March 21st 1772. Whether anyone was brought to justice I don’t know.

Perhaps the most enigmatic story or notice I read however was that printed on February 8th 1771.

“Whereas a person (supposed to be a Gentleman’s Servant) went out of Oxford, December 12th 1770 over Magdalen Bridge and took the Watlington Road riding a horse with a long tail and leading another with a cut tail on which a Portmanteau was tied: whoever recollects seeing the same person and can give information of his name and place of abode so that he may be spoke withal, shall on such proof receive half a guinea reward from the printer.”

Not exactly 50 guineas, but a very curious notice which has left me, as have the stories above, with so many questions. Who stole the lead and Mrs. Wise’s railings? Who carried out the robbery in Old Butcher Row – was it an inside job? And who was the man on the horse, leaving the city over Magdalen Bridge in the winter of 1770? Time – as far as I’m aware – hasn’t told so far. So, maybe I will.