“We have been living this same moment ever since we were conceived. It is memory, and to some extent sleep, that gives the impression of a life of discrete parts, periods or sections, of certain times or ‘highlights’.”

Bill Viola,‘Reasons for Knocking at an Empty House. Writings 1973-1994

“For although we know that the years pass, that youth gives way to old age, that fortunes and thrones crumble (even the most solid among them) and that fame is transitory, the manner in which—by means of a sort of snapshot—we take cognisance of this moving universe whirled along by Time, has the contrary effect of immobilising it.”

Marcel Proust, Time Regained

If the past is past and no longer exists and the future is yet to happen, then how do we, in the present, know about the past and experience the flow of time? In the here and now, there is no past and no future. So where are they? In Book XI of the Confessions, Augustine of Hippo concludes that they are within us:

“It is within my mind, then, that I measure time. I must not allow my mind to insist that time is something objective. When I measure time, I am measuring something in the present of my mind. Either this is time, or I have no idea what time is.”

In ‘The Order of Time,’ Carlo Rovelli writes; “…in the present, we see only the present; we can see things that we interpret as traces of the past, but there is a categorical difference between seeing traces of the past and perceiving the flow of time – and Augustine realises that the root of this difference, the awareness of the passing of time, is internal. It is integral to the mind. It is the traces left in the brain by the past.”

Things as events

In the same book, Rovelli writes:

“The world is not a collection of things, it is a collection of events… even the things that are most ‘thing-like’ are nothing more than long events.”

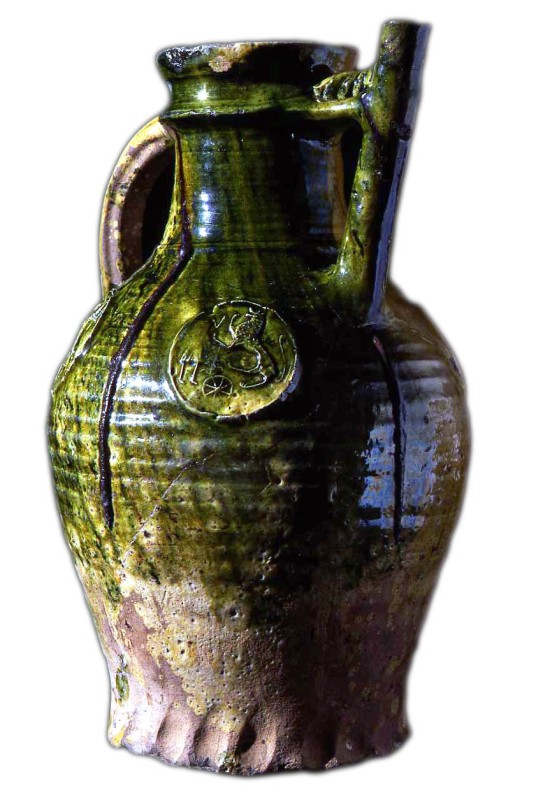

Like us, an object in a museum (for example, a mediaeval jug) is an event, and as an event, is just as much a part of the world today as it’s always been. Its use, function or value might have changed but as an event, the fact of its nowness now, is the same as it was 800 years ago when it was experienced in much the same way as it is today.

To borrow `Bill Viola’s quote above, this event (our mediaeval jug) has been ‘living’ this same moment ever since it was made, but it’s the lives of those who have ‘experienced’ the jug (their lives and deaths) over the centuries that gives the impression of a ‘life’ of discrete parts, periods or sections – the difference between now and then; a sense of history.

“There will no longer be any more reason to say that the past effaces itself as soon as it’s perceived, than there is to suppose that individual objects cease to exist when we cease to perceive them.”

Henri Bergson (1859–1941)

Measuring the past

When we cease to look at an object, that object remains within us as a memory, a snapshot which straight away begins to bleed into vagueness, much like a drop of ink spreads on a piece of paper. Our perception of the time that’s passed is also vague. It’s hard to relive a past moment with any degree of clarity (although music, objects and, in particular, place, can certainly sharpen our remembering senses). It’s also difficult to measure the flow of time with any degree of accuracy. How often is it that on recalling when someone famous died, the time that’s passed appears much shorter than it’s actually been?

We know the length of a year, and can, with that knowledge, imagine the span of 100 years or more, but only as we might walk a mile and contemplate a journey to the moon. As a rule to measure our lived experience (the flow of time as opposed to the fact of our age) units of time (months, years, decades) are of little use. Even less so as a means of perceiving, with any degree of accuracy, a span of several centuries past.

“Time – that’s what makes death so terrifying. The very idea of not existing – forever. But when you consider the past without recourse to a clock, when the past becomes that cloth bag of moments, then the future too – there on the other side of this thing we call the present – is just another load of moments waiting to go in the bag, to be jumbled up with all that’s gone before.”

Brief Castles

To ‘measure’ the distance to a past event and contemplate that place on ‘arrival’, we need to use our own memories and relationships as a yardstick, all bound up in the presentness of our own existence. When we think of times in the distant past, we do not consider them precisely as we do when measuring distance. The years are not arrayed within us sequentially along a line, but like our memories are mixed up together. If we’re looking at something made in 1588, we know it’s 290 years older than something made in 1878. But when we consider those times in which they were made, and try to imagine what they were like, our imaginations can’t discriminate between them in terms of a quantifiable length of time.

As I’ve written above, we are all events and as events are continuously linked to hundreds of other events; a network which, like a cat’s cradle, changes with every passing second as relationships are broken and new ones created. When we imagine a moment in the distant past, we have to try and imagine its events and the links between them.

[The city consists of] “…relationships between the measurements of its space and the events of its past; the height of a lamppost and the distance from the ground of a hanged usurper’s swaying feet; the line strung from the lamppost to the railing opposite and the festoons that decorate the course of the queen’s nuptial procession; the height of that railing and the leap of the adulterer who climbed over it at dawn; the tilt of a guttering and a cat’s progress along it as he slips into the same window…”

Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

“The trees ‘see’ the painter in a manner comparable to that in which the mirror ‘sees’ the painter: that is, the trees, like the mirror, let him become visible: they define a point of view on him which renders visible for him something that otherwise would remain invisible – his outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence… The trees and mirror function as Other.”

Christopher Tilley, ‘The Materiality of Stone, Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology.’

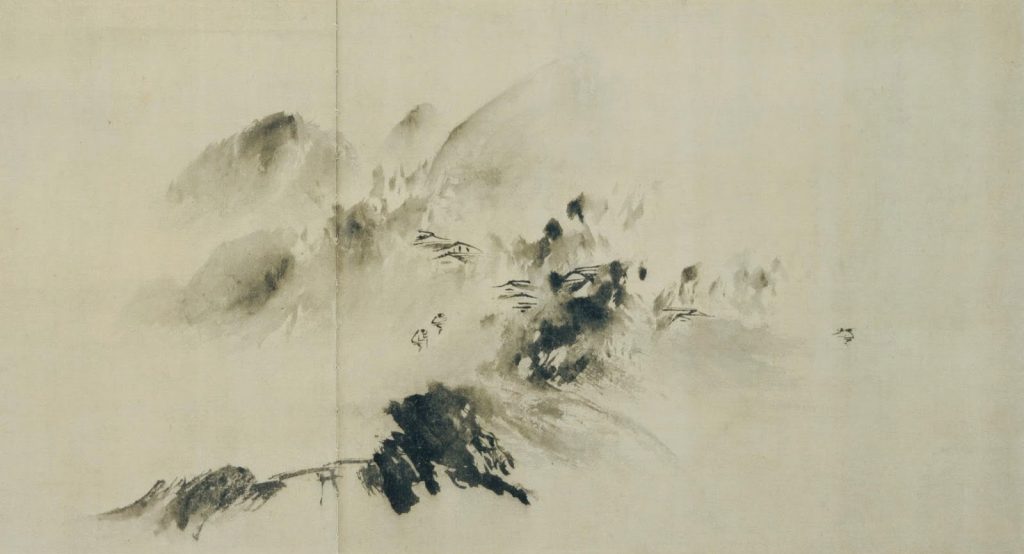

“Entitled Mountain Village in Clearing Mist by Yu Jian, the painting [shown above] was made all the more extraordinary on account of its age, made, as it was, around 800 years ago in the mid 13th century. This seemingly rapid work transported me to a time long gone. It revealed – much as with the Japanese haiku of Basho – an ancient and vanished moment, not so much through what it showed but how it was depicted. It was almost as if I could see the landscape before the painter himself. I could see the work as a whole (the landscape as a whole), but then, whilst picking through the gestures of the artist, evident enough in the brushstrokes, I could see the landscape as it was revealed. Yu Jian’s painting was not a painting of what was experienced, but rather the experiencing of what was experienced. It was almost as if the painting had become a painting, not of Yu Jian looking at the mountains, but of the mountain ‘seeing’ Yu Jian. It wasn’t the mountain that was made visible on the paper, but the artist himself – his presence at that moment. 800 years after his death, and Yu Jian was as good as sitting next to me. Or to put it another way, 800 years before I was born, I was as good as sitting next to him.”

Brief Castles

The age of a memory

How do we process the age of a memory? How do we ascribe an age to a time we’re imagining? Is it through a subconscious comparison between now and then, where the number of links between us and other remembered events are diminished (disorder) and where those memories or imaginings with the fewer extant links we recognise as the oldest?

Then

Then

Now

Now

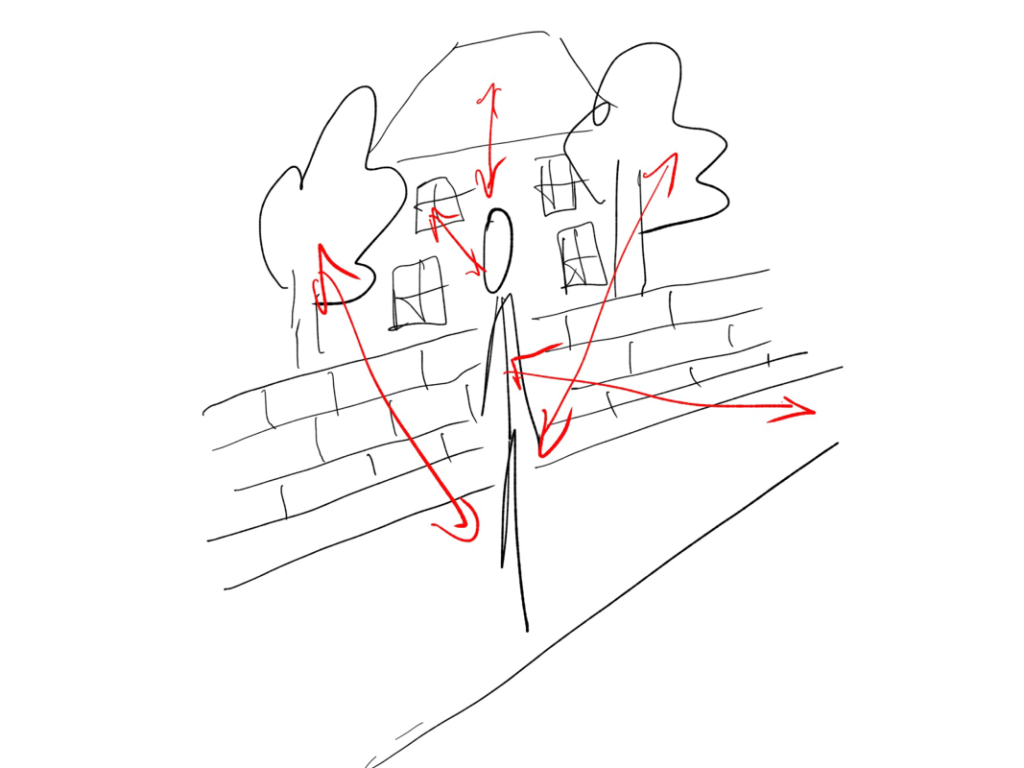

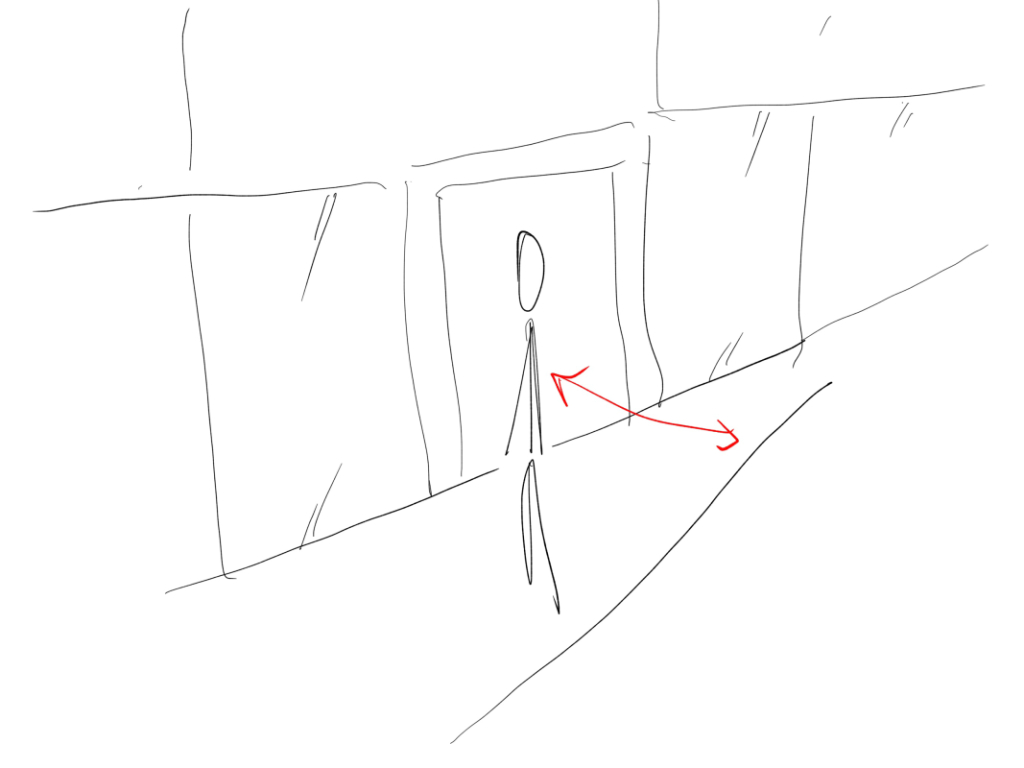

To ‘visit’ the past in our imaginations is to compare the world now with what the world was then (just as with our own memories we compare the same). It’s the scale of that difference (not the rule of years) which gives us the age – the degree of ‘pastness’. It’s the number of lines which link us to that past. When we look at our mediaeval jug we are linked to that jug by dint of the fact we’re observing it. When we walk in an historic place, the links – the lines – are greater, such is why, in these places, we can often gain a better sense of the past.

This internal time travel requires that entropy is reversed. We travel away from disorder. Relationships (links) are ‘re-established’ within our imaginations through the lens of our own memories and experience. When I was a child (and still as an adult), that meant rewilding the natural world; seeing the country still covered with ancient forests before they were felled.

Somewhere along the paths of those ancient woods, the long events (our family line) of which we are each a part continued in its presentness, coiled within people long since forgotten. Those forgotten people had memories of those paths – of the trees and dappled light on a summer’s day – just like the memories we have today of roads down which we’ve travelled. And those who carried these memories of the trees and the paths through the woods also carried their children, who in turn were to carry their own memories of their childhoods further down the line.

Of course once we’re travelled back in time, we have to imagine the world as if, like today, it was moving towards disorder; as if things were not fixed by history and that all its details were still filled with potential. Having established the links we need to break them.

In my previous post (‘Disordered Time’), I wrote with reference to some old photographs:

“These open windows therefore help us see the past moment as it happens rather than as it was. They ascribe the picture a duration and give it flow.”

That duration delimits a span of time – a flow – in the blankness of our own non-existence where a symmetry is found between now and then; between a time (now) when I’m alive and someone else is dead, and (then) when they are living and I am not yet born.

That duration – that flow – is a bridge; a means of establishing empathy.

“Trying to remember is itself a shock, a kind of detonation in the shadows, like dropping a stone into the silt at the bottom of a pond: the water that had seemed clear is now turbid and enswirled.”

Patrick McGuiness, ‘Other People’s Countries’

Also in my previous post, I looked at a photograph taken 125 years ago. I looked at a detail in the background of the image, of a man oblivious to the picture being taken.

“One can imagine him working and the effort he is making and the fact he’s unaware that he is part of the picture allows me to reach beyond the edges of the photograph. It’s as if, through his being unaware of the photograph, the boundaries of the photograph are dissolved and the moment is given rein to move.”

Boundaries of the photograph. Boundaries between life and non-existence.

Those details, whether they are open windows in 19th century photographs, brushstrokes on an 800 year old painting or ancient handprints on a cave wall are, for me, what Patrick McGuiness describes above as detonations in the shadows. They are the dropped stones agitating the image and the object, disordering time and ‘increasing entropy’.

If we imagine standing in the cave with these handprints before us, we can easily imagine the process of making them. If we were able to place our hands upon them, we could affect the same position as those who made them thousands of years ago. These links, lines or relationships help us back to the moment of their conception. But when we think of the world 35,000 years ago and what it looked like compared to ours, there are few links, lines or relationships left. The fewer the lines the older the time. The scale of disorder is vast. But that moment when a hand was painted is vivid and when set against the vast blankness of all the untold moments that make up the last 35,000 years, the sheer unlikeliness of our coming into being is dizzying. More so when we take that moment all those millennia ago and, like a ‘detonation in the shadows’, imagine its progress into the next moment and the next. And as we imagine the millions of lines, links and relationships which every second were, with the progress of those moments, made possible, we remember that 99.99999999% of them would have led to us never being born.

In a previous post (‘Entropy‘) I again referred to something Carlo Rovelli wrote in ‘The Order of Time’.

“The notion of particularity, is born only at the moment we begin to see the universe in a blurred and approximate way. Boltzmann has shown that entropy exists because we describe the world in a blurred fashion. He has demonstrated that entropy is precisely the quantity that counts how many are the different configurations that our blurred vision does not distinguish between.”

It was this line which took me a while to grasp: “He has demonstrated that entropy is precisely the quantity that counts how many are the different configurations that our blurred vision does not distinguish between.”

If we think back to the sandcastle and the pile of sand we can imagine the number of different configurations of each and can easily imagine that the number of configurations for the castle are far, far fewer than of the pile of sand. The castle therefore has few configurations that our ‘blurred vision does not distinguish between’ (low entropy) as opposed to the sand pile (high entropy).

When we think of a past moment whose future has been fixed in time we can borrow from the world of physics and say it has low entropy. But when we consider the details of a moment (the distant man oblivious to the photograph, Yu Jian’s painting in progress) and all the lines, links and relationships formed and broken with every passing second, we can say that, in our imaginations, the same fixed moment acquires greater entropy as we consider all the possible moments that could arise.

To climb the peaks of our imagination and see a time long before we were born is, at the same time, to descend into the depths of our own non-existence, wherein which dark expanse, our imagination lights the dark as it does the paths that lead away from our deaths. Imagination and memory come together to blur the boundaries of our beginnings and ends, as if, like a book, the unseen words that might have been written before and after are suddenly revealed in all their infinite number.