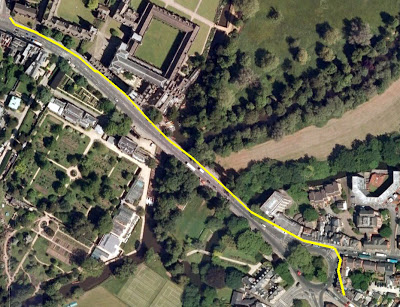

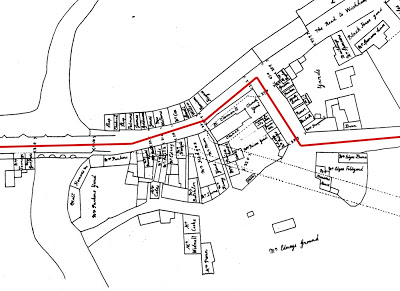

With my GPS, I traced the route we know the Gentleman’s Servant took across Magdalen Bridge up into modern day Cowley Road. It was hard to imagine the scene in 1770 when the road would have been much quieter. Cars, buses and motorbikes were everywhere, the sound of their engines blocking out almost everything else.

But nevertheless, as I walked, I tried to take in everything around me, to capture all that made the present moment what it was, for even though the same place in 2010 is light years away from what it was 240 years ago, nevertheless, when the stranger rode over the bridge on December 12th 1770, it was something which for him was happening in the present. Now this might sound an obvious thing to say, but often when we read about the past, it’s almost as if we’re reading a fiction – a story which has a beginning, a middle and an end, and in which the characters follow a proscribed route laid down by the author: the narrative line in this instance comprises the text which makes up the tale. Of course life isn’t like this. When we walk, even if we’re going somewhere particular, we walk without knowing what may lie ahead of us. We might well know where we’re going, but how we’ll get there exactly, and what will happen as we travel, is something we only discover in the present moment.

As I wrote as part of a recent exhibition:

The Past is Time without a ticking clock. A place where paths and roads are measured in years. The Present is a place where the clock ticks but always only for a second. Where, upon those same paths and roads we continue, for that second, with our existence.

I want to read history in terms of its seconds – the small spaces within which life really happens. Every second in the present day – every moment – is a lens through which we can glimpse the past, no matter how distant it is. The more we know about the past (in particular the ‘geography’ of whatever we’re researching) the better the picture. But something in the space of every second reminds us, that what happened in the past happened in what was then a present just like ours; something as a simple, for example, as trees blowing in the wind.

The narrative line is like a piece of text; we follow it as we follow the words of a sentence, putting one foot in front of the other. But reading between the lines, we fill the gaps with what we see and experience around us. We are reminded that the stranger was moving all those years ago, unaware of what might lay before him. We become aware that he could feel the wind on his face, that he could see the sky, the river flowing beneath the bridge. And as we think, we realise that he himself was thinking, as was everyone around him – and this is the key to answering the questions I posed at the beginning of this project.

Every second the stranger rode along that line, he was part of a complex web of connections. These moments comprising his story were moments in many others – countless stories in a plot more complex that we can imagine. The more we know about these moments, the more we can picture the scene and all who lived at the time, the better the chance we have of finding answers.

As I walked the length of the line, I looked to my right and glimpsed the 17th century gateway to the Botanic Gardens, and in that gesture, I found a connection with the stranger. The gateway is a witness to the moment I’m researching, and looking at it is one way of asking it for an answer.