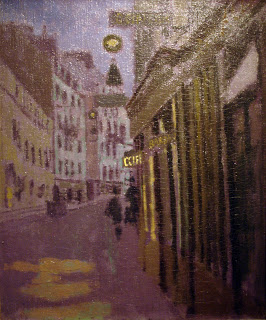

The photograph below is a rather poor reproduction of a painting hanging in The Ashmolean museum, Oxford. It is perhaps, my favourite painting in the museum. Painted by Walter Sickert (1860-1942), it’s one which I have stood before for some considerable time, not least quite recently in order to write the following.

In my previous entry, regarding Cy Twombly’s Panorama, I discussed, albeit briefly, how it was quite impossible to fully appreciate a painting through a reproduction. Of course that much is obvious, but I wanted to write about this particular work to see just how differently I perceived it compared with the work by Cy Twombly, which, as I say, I’ve only ever seen in a book.

As can be seen from the photograph, one of the things I noticed straight away about this painting was the light reflecting off its surface. Not really anything to do with the painting perhaps, but, nonetheless it forced me to move, to find an angle where I wouldn’t be dazzled, and by doing so, I discovered something about the painting itself. What’s important here, is the fact that a painting isn’t just a surface on which paint is applied (although the appreciation of surface and texture can only be attained when faced with the real thing). Instead, a painting is as much about the space around it. Of course, Walter Sickert would have no idea that his painting would one day grace a wall in the Ashmolean museum, dazzled by the lights. But he would have walked whilst painting it, or rather moved before the easel. He would have stood in front, to the left, to the right, and this movement in the act of painting is, I believe, important in the act of viewing and appreciating the result.

So what do we see in this work? Well, it’s a road in Paris (the rue Notre-Dame des Champs), one on which the painter John Singer Sargent had a studio. Given the muted palette and bruised sky, the picture shows a scene from about that time of day when the night begins removing all the colours from the world, when the last light in the sky, makes all manner of colours that seem to last for just a few seconds. It’s a wet end to a day that’s more than likely seen nothing but rain. The concertinaed facades of the shops with their heavy paint dragged down the surface, the downward strokes of the windows in the buildings opposite and the vague forms from which the scene’s almost entirely comprised, all suggest the fading light and drenched air of an autumn or winter evening.

There are puddles in the street which soak up the sickly light of the cafe like a man with a sponge mopping up blood after a brawl. The road is somewhat sickly and the light of the cafe offers us a refuge from whatever is coming just around the corner. Two or three figures stand just ahead. Are they moving? Are they walking towards us? Away? It’s hard to tell. But a feeling of isolation, pervading the picture, is I believe augmented by their presence.

As I moved before the painting, shifting my weight from one foot to the other, the colours seemed to shift. The bluey-violet sky shimmered above the drowned buildings, and the reflections in the road revealed new colours the more I looked. Looking at the painting in the flesh, I felt – compared with looking at the reproduction above – that my eyes had to move in order to cross from one side to the other. In a reproduction, the spaces are of course greatly reduced and everything can be seen or grabbed in an instant. In the flesh (and this painting is very much about the physicality of the world) you look as you might when standing somewhere in town. You look with more than just your eyes; you experience the painting with your body; one that stands alone before the canvas.

Returning for the moment to the glare of the lights, I found that when I looked at the painting from the right hand side, the glare subsided, and that all that remained were just a few specs where the paint was raised above the rest of the surface. Furthermore, from this position, the painting seemed to open up, as if the concertinaed lines of the shop facades were being pulled, expanding like bellows. Here, the street seemed to pull me on. Standing directly in front, it almost seems about to collapse upon itself.

I’m not trying to suggest that this is all deliberate on the part of the artist, but to emphasise the fact that the act of looking at a painting is a physical experience. Sickert would have known this street, he would have recalled what it was like to stand there. He would have moved before the canvas as he painted, and, as a viewer, the way I stand and move before the canvas reflects that. It is, in the end, the only way to get to know art.