Between 29th October and 18th November 2010 I will undertake a residency at The Lock Up Cultural Centre in Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia. Aside from being a great adventure – travelling from the UK to the other side of the world – it will be an excellent opportunity to explore over a period of 3 weeks, those themes which I’ve been researching over the past few years, namely the past, the present, history and the embodied imagination.

Performance and its relationship to walking – and also archaeology – is something I’ve been looking at of late, and through exploring the city of Newcastle and working with video and installation inside the cultural centre, I shall look forward to seeing how that particular area of my practice might be developed.

The inspiration behind this residency will be the life of my great great great great uncle, Stephen Hedges, who in 1828, at the age of 20, was transported to Australia for stealing 154lb of lead from a house in Radley. The following is taken from my existing blog:

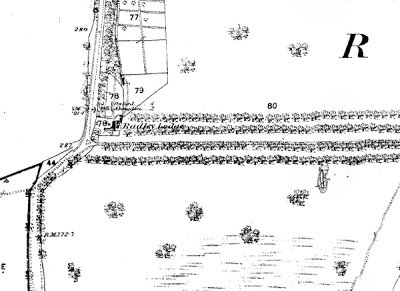

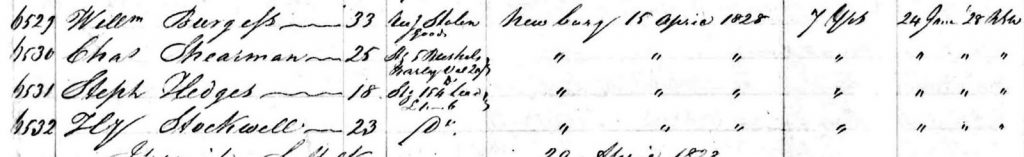

On Monday 28th January 1828, a sawyer by the name of Richard Burgess was travelling from Abingdon to Oxford with a cartload of bone for sale in town. On the road to Oxford, Burgess met with three men; Stephen Hedges – a young Abingdon man in his late teens, Henry Stockwell, originally from Aberdeen and a few years older than Hedges, and a man called John Harper. Hedges – described later by Stockwell as the ‘captain’ as regards the events about to follow – asked Burgess if he was going to Oxford and whether he’d carry a parcel for them. Burgess agreed, at which point Harper left the group, while Hedges and Stockwell continued on towards Oxford with the cart.

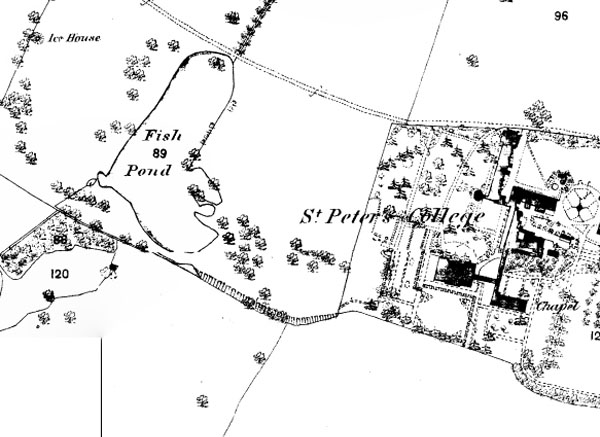

On the Oxford Road, near the lodge of what was then Radley House, Burgess was asked to stop. At first Burgess refused, but relented, stopping as he said later for about five minutes. At that time the house was owned by Sir George Bowyer (who in 1815 had been forced to sell its contents to help his struggling finances) and rented from him by a Mr. Benjamin Kent. When Harper arrived back on the scene with a bag, the three men went off into the gardens.

After five minutes the men returned carrying the bag which Burgess described as being very heavy. What was in the bag, Burgess didn’t know, but given that Stockwell was carrying a piece of lead on his shoulder, it must have been obvious.

On the way into Oxford, the men – still travelling with Burgess – met a Charles Jones whereupon, according to Burgess, they engaged in conversation. Burgess went on into Oxford, to Mr. Round’s wharf and near the gates set down the lead and delivered his cargo of bone for weighing. Half an hour later, Stockwell and Jones reappeared and put the lead back on the cart. Burgess asked him where they were going to take it, to which he was told to follow Jones.

Burgess followed Jones up the ‘City Road’ and near the Castle met with Hedges and Harper. They turned back through Butcher Row to the place where the lead was to be delivered, and here, for his trouble Burgess was paid sixpence.

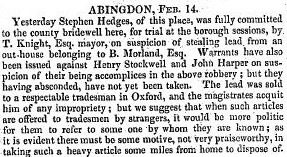

The next day, on Tuesday 29th January, James Smith, servant to Benjamin Kent, discovered three ‘hips’ of the larder roof had been stripped of their lead. Two weeks later, on Wednesday, 13th February, Stephen Hedges appeared in Abingdon before the mayor T. Knight Esq. on suspicion of stealing lead from an outhouse belonging to B. Morland Esq. (I’m assuming here that B Morland and B. Kent are in fact the same person). He was fully committed to the Bridewell whereas Stockwell and Harper were, at that point, still on the run.

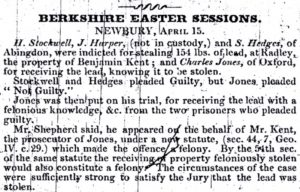

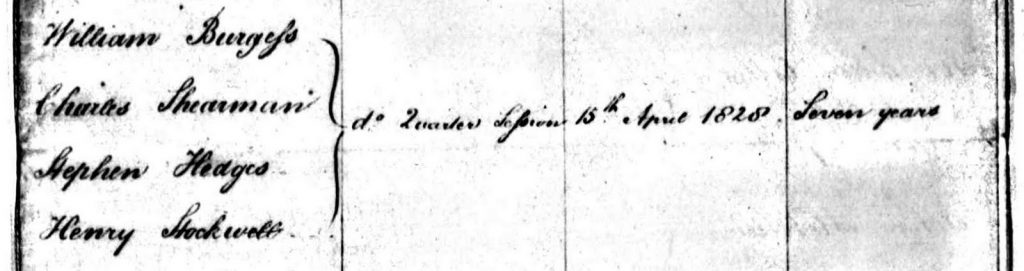

Justice however soon caught up with them, and together with Hedges they were tried at the Berkshire Easter Sessions on Tuesday, 15th April. Stephen Hedges and Henry Stockwell were found guilty of stealing 154 lbs of lead. The sentence passed was transportation for a period of 7 years. The report in Jackson’s Oxford Journal makes no mention of Harper’s fate. Charles Jones was acquitted.

Having been convicted and sentenced, Hedges and Stockwell were taken to Portsmouth, and on Monday 28th April, received aboard the prison hulk York.

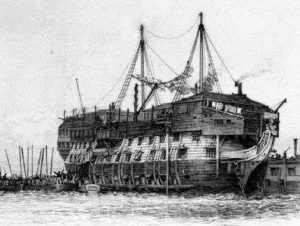

The system of prison hulks had been established by an act of Parliament in 1776 (following the declaration of American Independence which meant the loss of penal colonies there) to ease overcrowding in British prisons. Old warships moored on the Thames and those in other ports, were converted into prisons, and despite the terrible conditions suffered by the prisoners within, the system remained in place for another 80 years.

The York, in which Hedges and Stockwell were incarcerated, was the eighth ship in the Navy to bear the name and had once been a 74-gun, third rate of 1,743 tons. Launched in 1807, she’d been posted to the West Indies where she was involved in the capture of the island stronghold of Martinique. She continued the war in the Mediterranean Squadron off Toulon and in 1819, returned to Portsmouth to serve as a prison hulk – home to some 500 inmates.

Entering a hulk was demoralising to say the very least. Prisoners were stripped of their clothes, after which cold buckets of water were thrown over them. They received their slops and looked on as their own clothes were thrown into the sea – a baptism of their status as a convict and a ‘ceremonial drowning’ of their lives before that time. Finally, they were led into the darkest, foulest-smelling parts of the ship, to await their transportation – the last stage in the process of being forgotten.

The final column of the York’s Muster reads rather ominously: how disposed of?

And this is just what was being done with all the men and women sentenced in this manner. In this column, next to the names of Stephen Hedges and Henry Stockwell, are the words: 24 Jun ’28 NSW; NSW being their final destination – New South Wales.

The York’s documentation also tells us something – albeit somewhat succinctly –about Stephen Hedges’ character. Whereas other prisoners are described as being badly connected, not known here, orderly or good in gaol, Hedges is described simply as bad. To be fair to him however, he wasn’t described as being very bad, which was a term applied to a certain John Head, who was being shipped abroad for 7 years for receiving stolen goods.

Conditions aboard the York were appalling, and Stephen Hedges and Henry Stockwell had to endure them for 2 months before they left for New South Wales, Australia. Finally, on Sunday, 29th June 1828, they left Portsmouth on the convict ship The Marquis of Hastings never to see England, or their families, again.

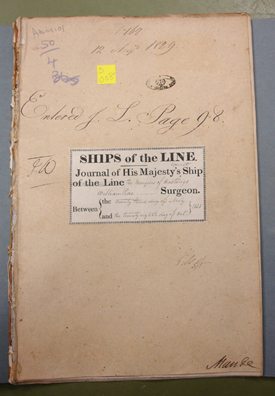

The journey to New South Wales took them 4 months and onboard the ship, travelling with the crew and the prisoners was the ship’s surgeon William Rae, who, as part of his duties, kept a journal of illnesses and treatments suffered throughout the voyage.

Given the length of the voyage, the appalling conditions and the terrible diet the prisoners (and indeed the crew) had to endure, it’s surprising that so few people passed through William Rae’s sick bay. In total, 17 people were in his care during the course of the voyage, of whom 13 were discharged cured and 3 discharged convalescent in Sydney. Only one person died – from Hydrocephalus (water on the brain).

During the voyage, Rae made notes on the weather which, even in brief descriptions of the clouds, paints a vivid picture of the journey. For example: July 24th 1828. The ship was located at Latitude 10.2o N and Longitude 23.50o S. The temperature was 80oF with a light West-South-Westerly breeze. ‘Cloudy with rain’ Rae has added, in the column marked ‘weather for the day’.

We might not know how it feels to be fettered by the ankles and the waist, locked inside a cramped, stinking space with dozens of other criminals, but we all know the weather. When we read about the conditions suffered by the convicts, it always seems – so long ago did it happen – comparable to a fiction. Strong breeze, squally with rain however is just as much a part of now. When we look at a cumulus cloud as Rae had done, we can get a little closer to the plight of the convicts in the hold.

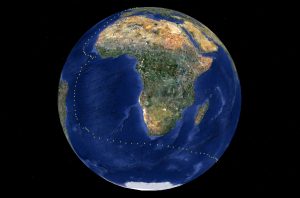

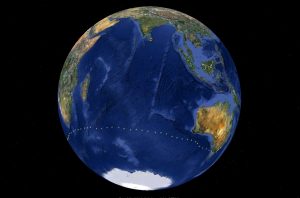

Plotting the coordinates of the voyage allows us to see the journey. The following stills are taken from Google Earth, in which I plotted Rae’s longitude and latitude.

Stephen Hedges would have had no idea what to expect in Australia, and the same could be said for most of those onboard. Australia itself had only recently emerged from the world of myth. It was still little more than an outline, a vast oubliette for the convicts on board.

On maps throughout the 18th century, Australia’s outlines slowly emerged, as various explorers happened upon her shores. It seems inconceivable that so vast a landmass could ever have been missed, but it just goes to show how big the oceans are by which it is surrounded.

The contrast between its (then) vague geography, its being a kind of oubliette and the realities of the present along with its unforgiving landscape, is something which interests me a great deal.

After four months at sea, bound for New South Wales, the prisoners disembarked at Sydney, on Tuesday, October 28th.

Stephen Hedges was assigned to James Bowman who’d been appointed principal surgeon for New South Wales after arriving on the John Barry in 1819. By 1832, Bowman had established a sheep run on more than 11,000 acres of land at Ravensworth, Patrick Plains. Hedges may well have been used to help construct it.

Detail from NSW 1828 Census, showing Stephen Hedges being assigned as a labourer to James Bowman at Patrick’s Plains.

On 24th December 1838, Stephen Hedges, now a free man, married Elizabeth Carter in Parramatta, New South Wales.

He died in Australia in 1885, at the age of 74.