The Past is Time without a ticking clock. A place where paths and roads are measured in years. The Present is a place where the clock ticks but always only for a second. Where, upon those same paths and roads we continue, for that second, with our existence.

This is the third in a series of exhibitions inspired by a visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau in October 2006. Since that time I’ve visited camps at Bełżec, Majdanek and Natzweiler-Struthof, as well as the battlefields of Ypres, Verdun and more recently, The Somme. All these sites present the tourist with numbers: 1.1 million dead at Auschwitz-Birkenau, 500,000 at Bełżec, 79,000 in Majdanek. At the start of the Battle of the Somme, on 1st July 1916, British and Commonwealth forces sustained 57,000 casualties, with almost 20,000 men killed in action on that day alone. These are all horrific statistics, but numbers rather than people and over the course of the last 4 years, I’ve looked for ways of finding and identifying with, the individuals behind the grim tolls.

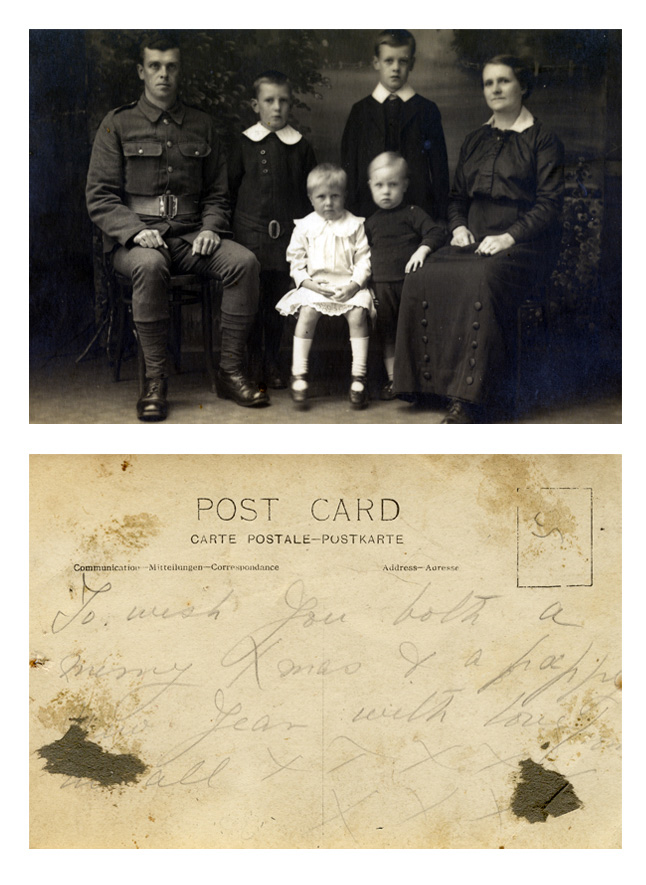

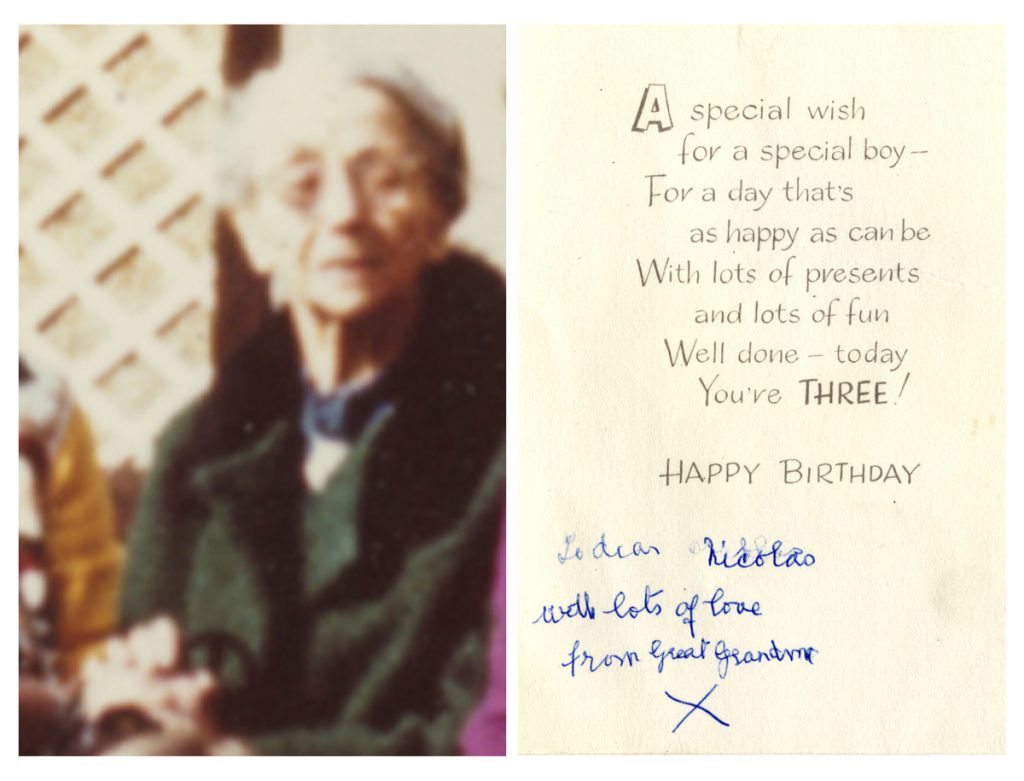

Most of these individuals have left nothing behind; no name, possessions, or photographs. Photographs, where they exist, are often nameless, names on graves are faceless, so how can we know them at all? An answer came as I researched my family tree, as I tried to find those anonymous individuals to whom I was related.

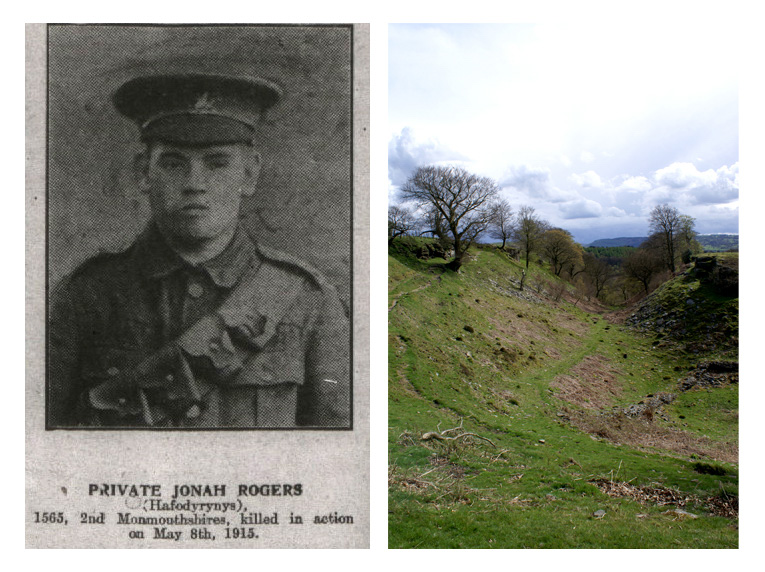

In 2007, the year before she died, my grandmother told me about her childhood in Wales. The following is an extract from that conversation in which she describes her father:

‘I can see him now because he went up our garden over the road and the mountain started from there up… and he’d go so far up and he’d turn back and wave to us, and if we went out to play, our Mam would say, ‘you can go up the mountain to play…’ but every now and then our Mam would come out in the garden and we had to wave to her to know that we were alright you know… always remember going up the mountain…’

On visiting Hafodyrynys, the small town where my grandmother grew up, I walked up the ‘mountain’ she’d described and followed the path my great grandfather would have taken to work in the mines at Llanhilleth. On top of the hill I stood and looked at the view. 100 years ago, when I did not exist, he would have seen the very same thing. 100 years later, long after his death, I found myself – through being in that place – identifying with him: I’d found him on the path (one which would in time lead to my being born).

One of the problems we face in identifying with those long since lost to the past, is how to bridge the temporal gap between us. The past has been ‘written’. It’s like the words in a book; years follow years like words in a sentence, like sentences that make up the page. For us in the present, those words are always in the course of being written. The paths our ancestors took through life are fixed, as if they’d always been so, as if they followed their lives like actors in a play, following directions, reading the lines written for them. But nothing ever happens in the past, what happened did so in what was then the present – a present which always lasts only for a second. But in that ‘space’ of every second life happens; we hear the birds, we see the sun, feel the wind and rain. In that space, all our hopes are held, all our fears and regrets. Into that space we carry our pasts in the form of memories. It’s the space of the everyday – one which we often take for granted. But it’s a space we share with everyone who’s ever gone before us.

As I walked along the path, atop the ‘mountain’ in Hafodyrynys, I looked up from watching my feet and caught a glimpse of the clouds. I noticed the trees moving in the wind. I traced, for a second, the long line of the horizon. I did the things my great grandfather would have surely done as he walked to and from work. I can never know what it was like to work down the mines, but I know what it means to be in the present, and this is something shared by everyone over time.

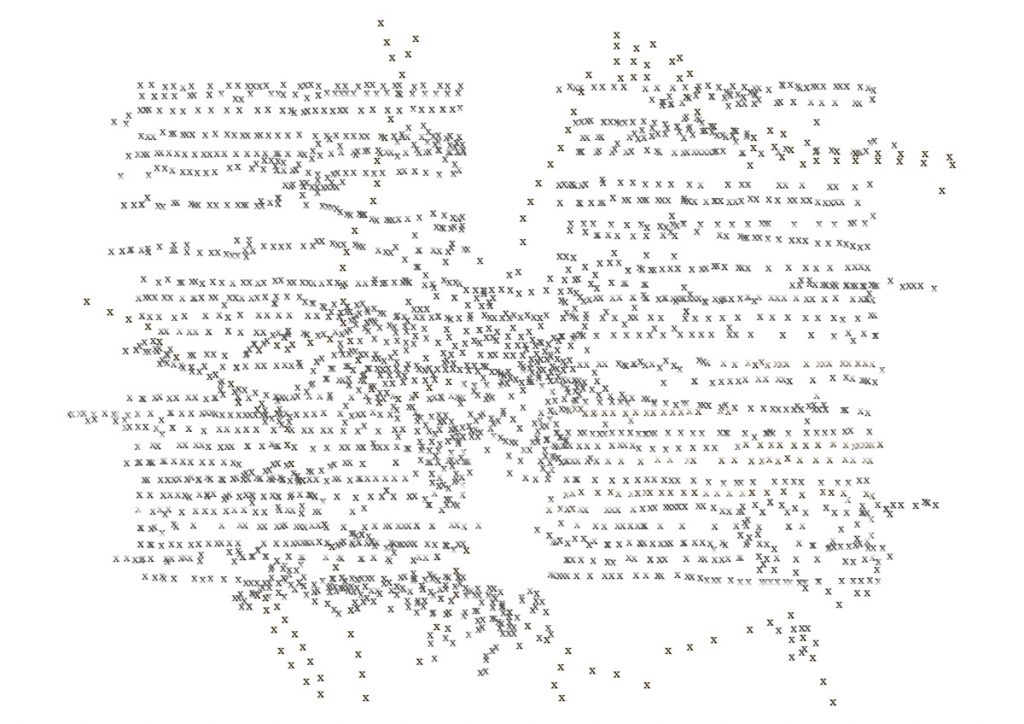

The idea of paths as text is something which appeals to me; the notion that as we walk we ‘write’ ourselves in the landscape. In his book ‘Lines, a Brief History,’ Tim Ingold writes that ‘human beings leave reductive traces in the landscape, through frequent movement along the same route…’. The Old English word writan he tells us, meant to ‘incise runic letters in stone.’ A correlation can therefore be found between the act of walking and writing; a path is something written over years by many different people.

Christopher Tilley, in his book, ‘The Materiality of Stone – Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology,’ writes that ‘If writing solidifies or objectifies speech into a material medium, a text which can be read and interpreted, an analogy can be drawn between a pedestrian speech act and its inscription or writing on the ground in the form of the path or track.”

Again, Tim Ingold in his book, ‘Lines. A Brief History,’ tell us that:

‘…from late Antiquity right through to the Renaissance writing was valued above all as an instrument of memory. Its purpose was not to close off the past by providing a complete and objective account of what was said and done, but rather to provide the pathways along which the voices of the past could be retrieved and brought back into the immediacy of present experience, allowing readers to engage directly in dialogue with them and to connect what they have to say to the circumstances of their own lives. In short, writing was read not as a record but as a means of recovery.’

Walking therefore can be seen in the same light. As on the ‘mountain’ in Hafodyrynys, it’s a means of recovering the past, of engaging directly in a dialogue with those who’ve gone before us, and nowhere is this more keenly felt that in places of historic trauma.

Far from being empty, places like Auschwitz-Birkenau and the battlefields of The Somme are full of lines; paths followed and written by hundreds of thousands of people. And just as I followed the path of my great grandfather, so in these places we follow and read the paths of all who died. We can never know what it was like to be there, but we can know what it’s like to be there in the present. So as I walked from the Ramp in Auschwitz-Birkenau, down towards the gas chambers, as I walked across No Man’s Land in Ypres and The Somme, I caught a glimpse of the clouds, I felt the wind and saw the sun. I felt the ground beneath my feet and read with my body, the words of those who’d gone before me.

In his book, ‘This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentleman,’ Auschwitz survivor Tadeusz Borowski writes:

‘Do you really think that, without hope such a world is possible, that the rights of man will be restored again, we could stand the concentration camp even for a day? It is that very hope that makes people go without a murmur to the gas chambers, keeps them from risking a revolt, paralyses them into numb inactivity… Never before in the history of mankind has hope been stronger than man, but never also has it done so much harm as it has in this war, in this concentration camp. We were never taught how to give up hope, and this is why today we perish in gas chambers.’

As I wrote before; in that ‘space’ [called the present] life happens; we hear the birds, we see the sun, feel the wind and rain. In that space, all our hopes are held, all our fears and regrets. Into that space we carry our pasts in the form of memories. It’s through that space that we can identify in some small way with those who’ve left no other trace.

In his book, ‘Reasons for Knocking at an Empty House,’ artist Bill Viola writes:

‘We have been living this same moment ever since we were conceived. It is memory, and to some extent sleep, that gives the impression of a life of discrete parts, periods or sections, of certain times or highlights.’

The lines we trace and read in sites of trauma are of course fragments. They often represent the last few seconds, minutes or hours of someone’s life, but in reality, each one of those who died carried with them a lifetime of memories, just as we carry our own when as tourists we visit. Many of those who died in these places left no trace behind. Photographs are nameless, names are faceless and yet we can know them a little. By being in those places, by ‘reading’ with our bodies the fragments of texts left behind, we can share in what it means to be present. And where there are gaps in the text, we can fill in what is missing with that of our own existence.