Art is the search for a ‘way-in’ to a subject and the artist’s role is in keeping that ‘way-in’ open so others might follow.

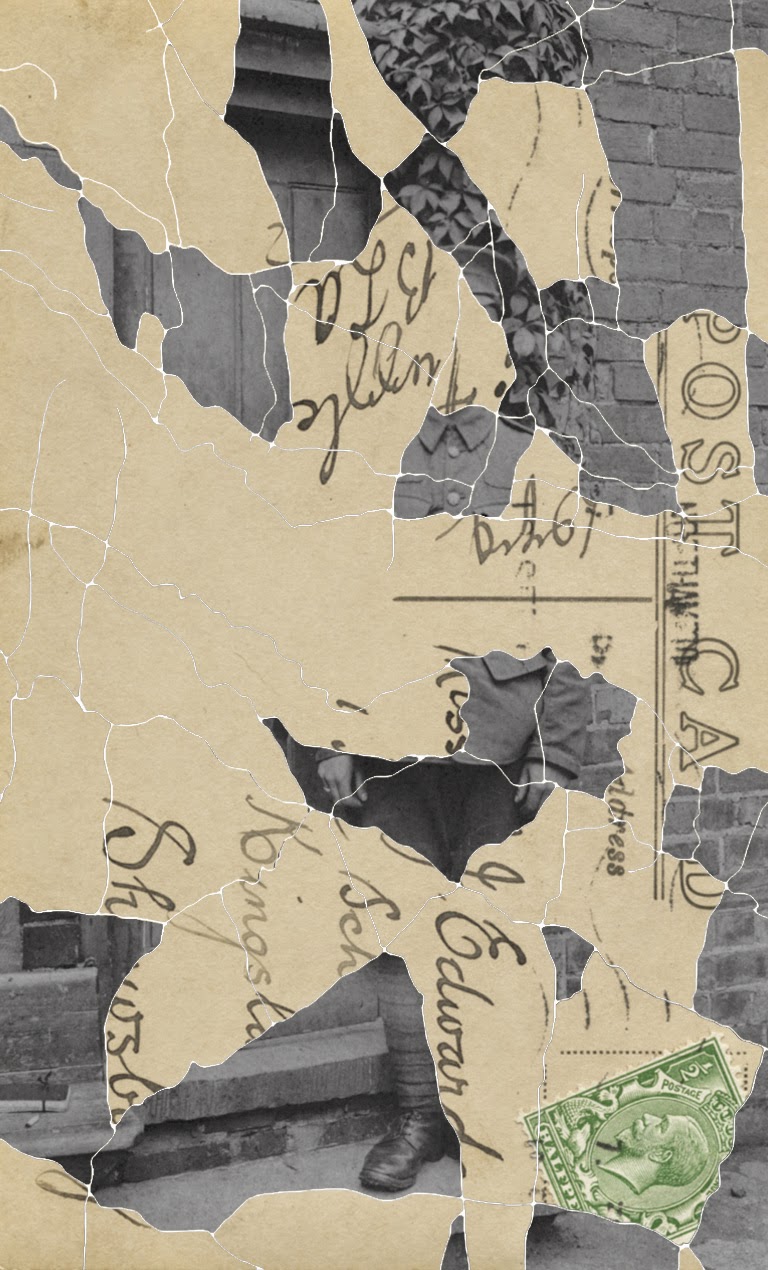

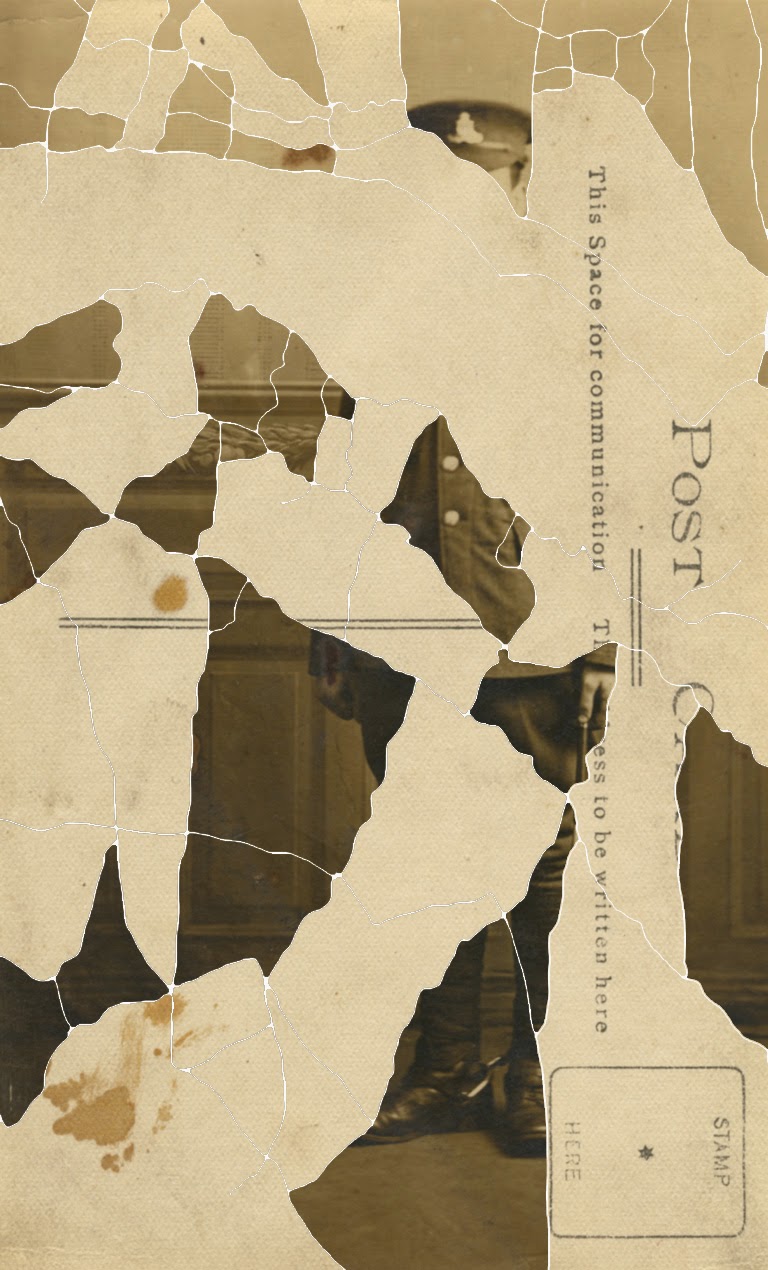

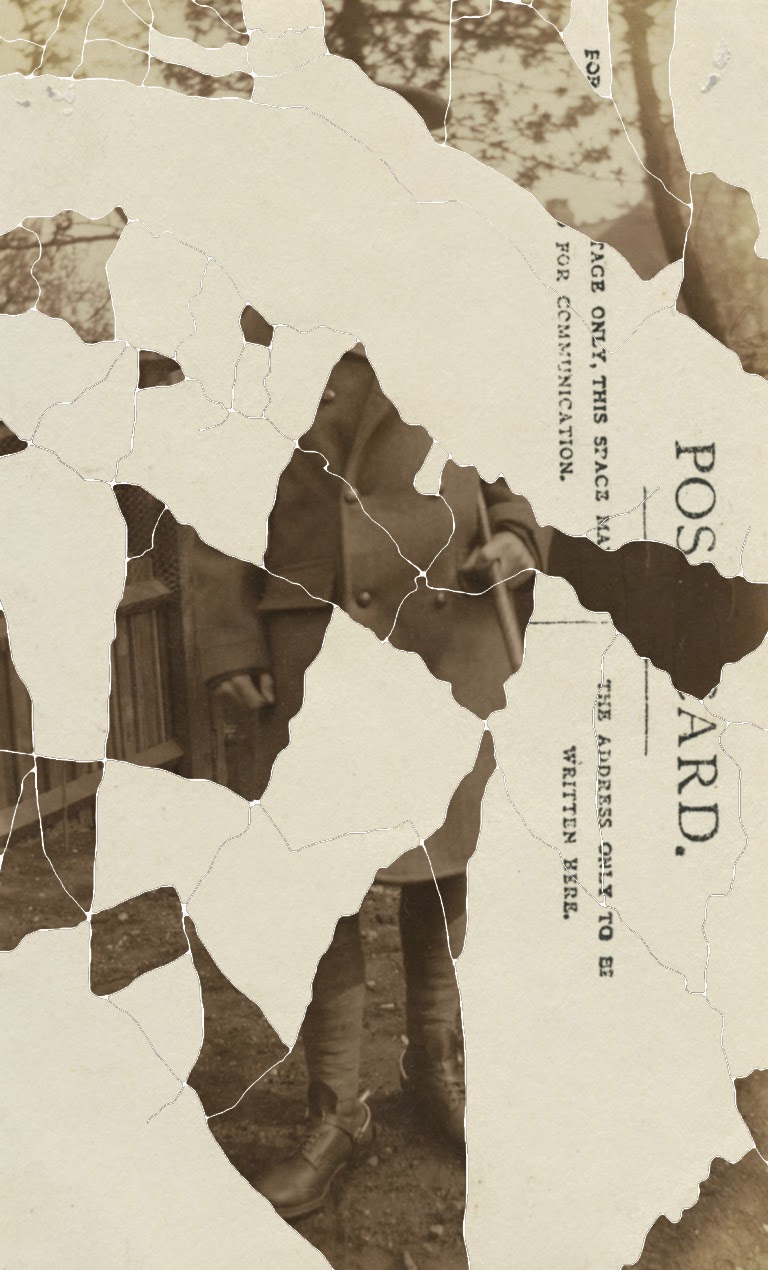

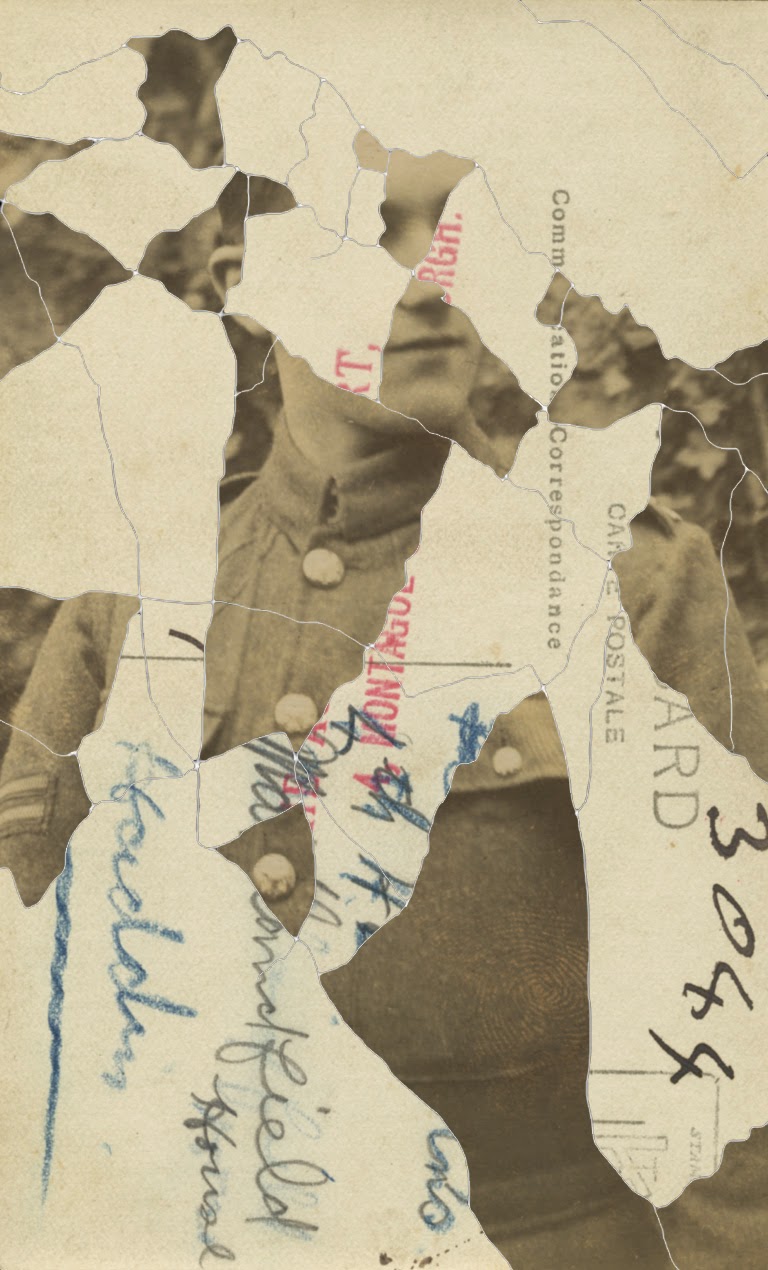

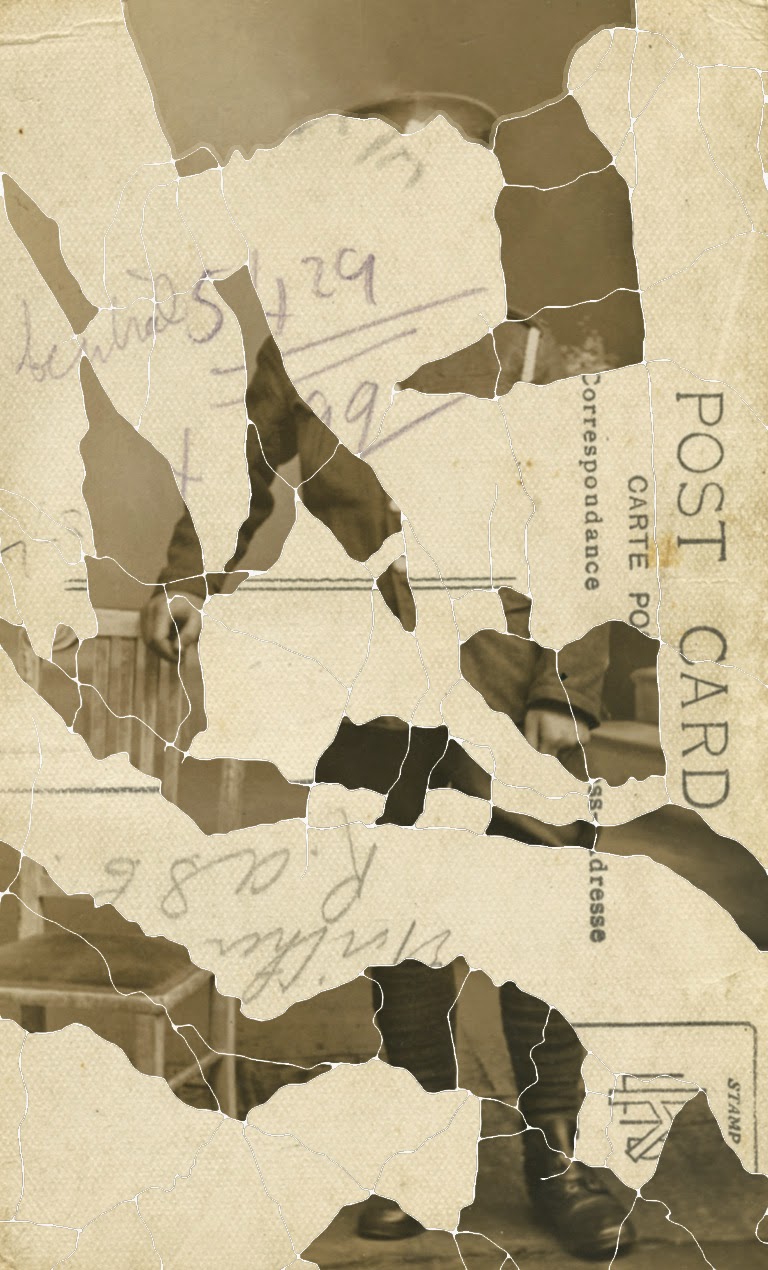

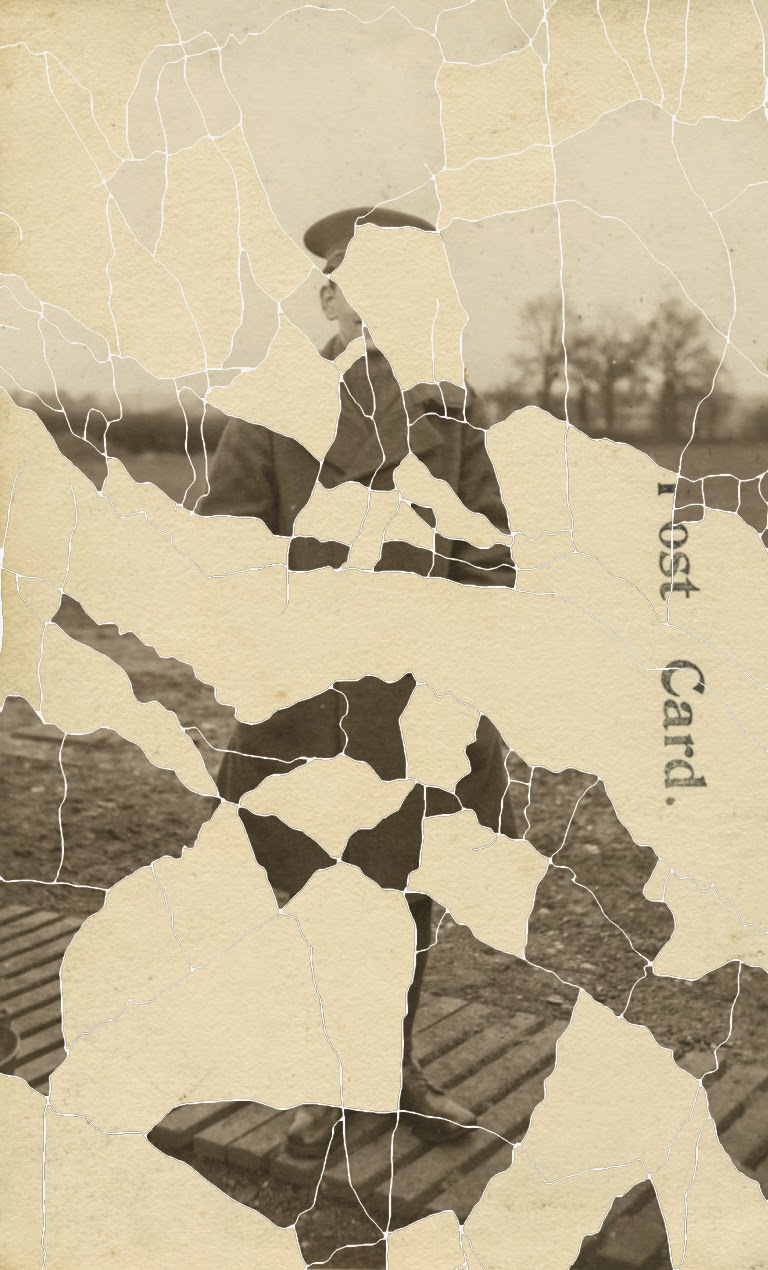

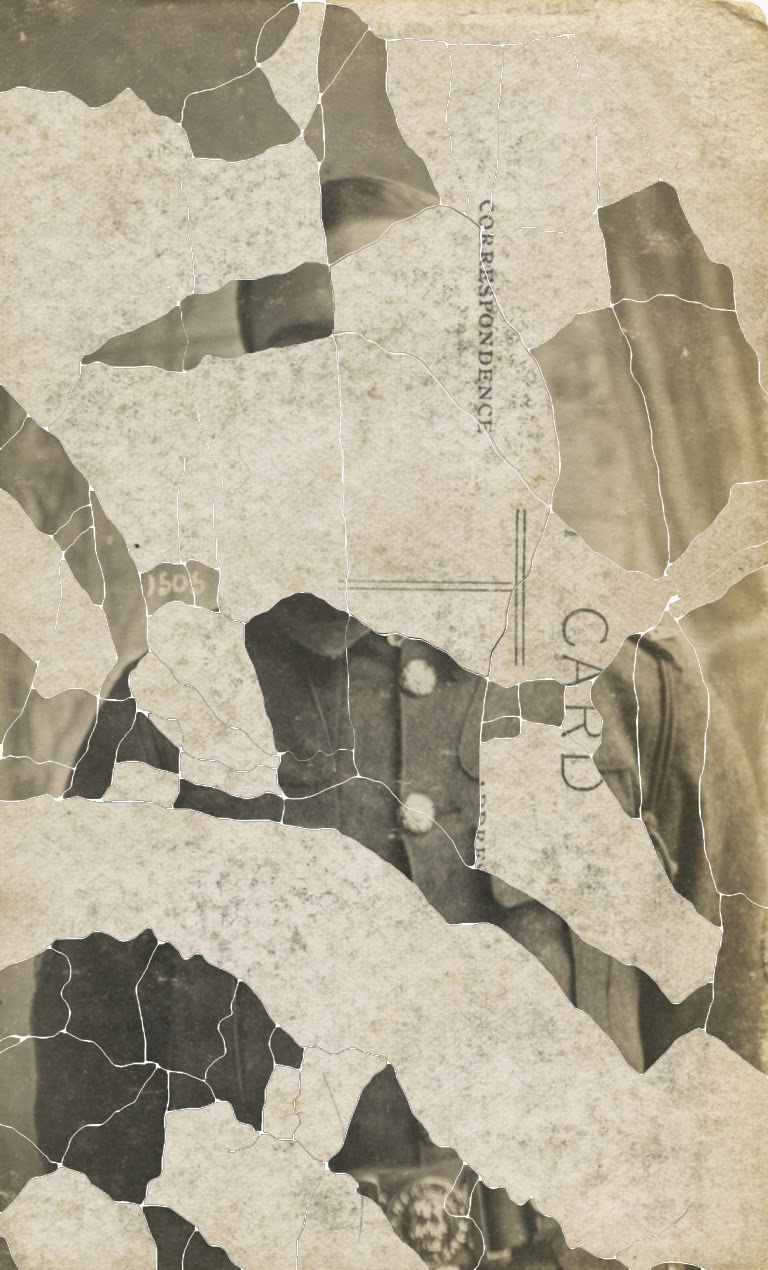

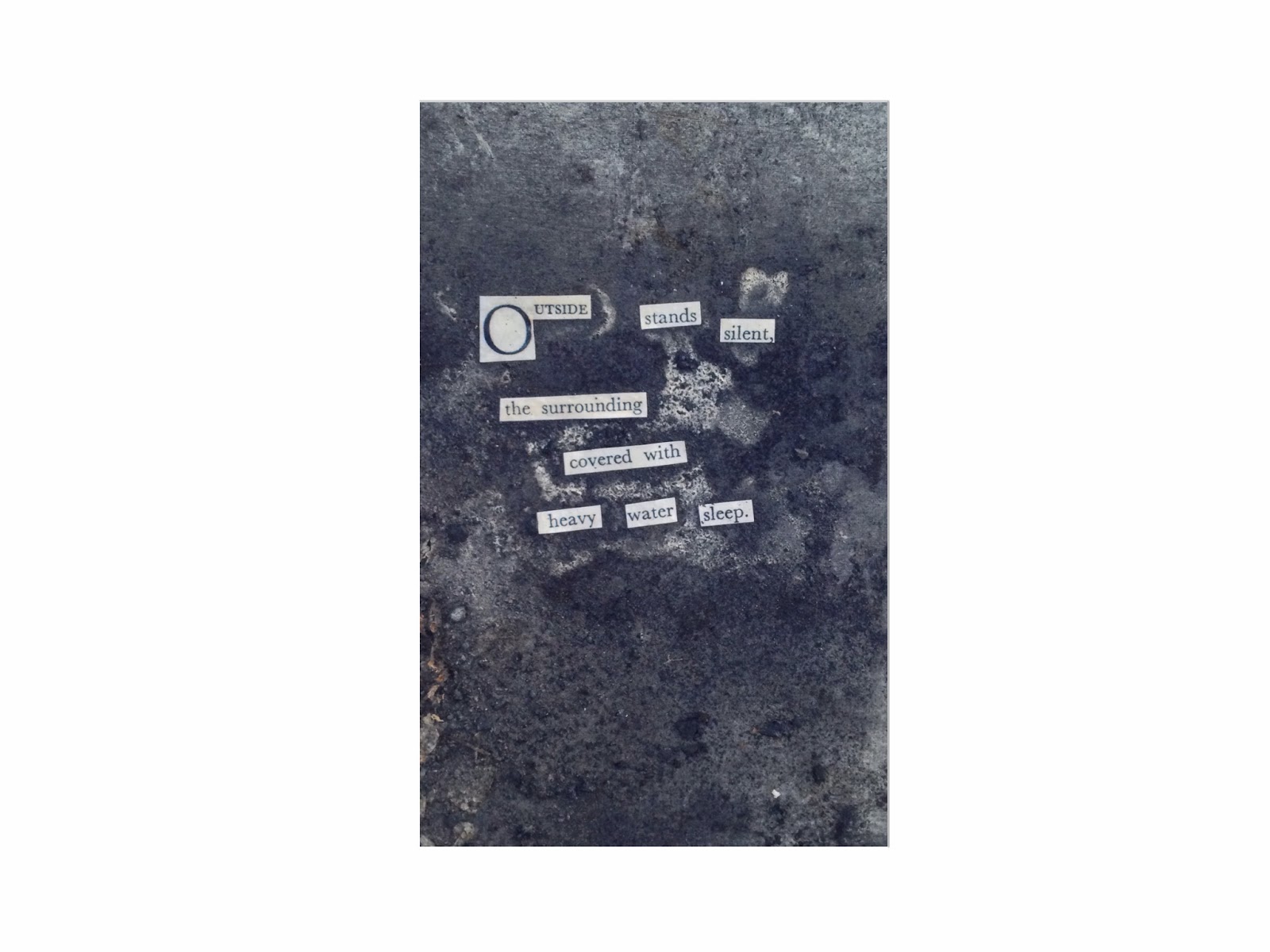

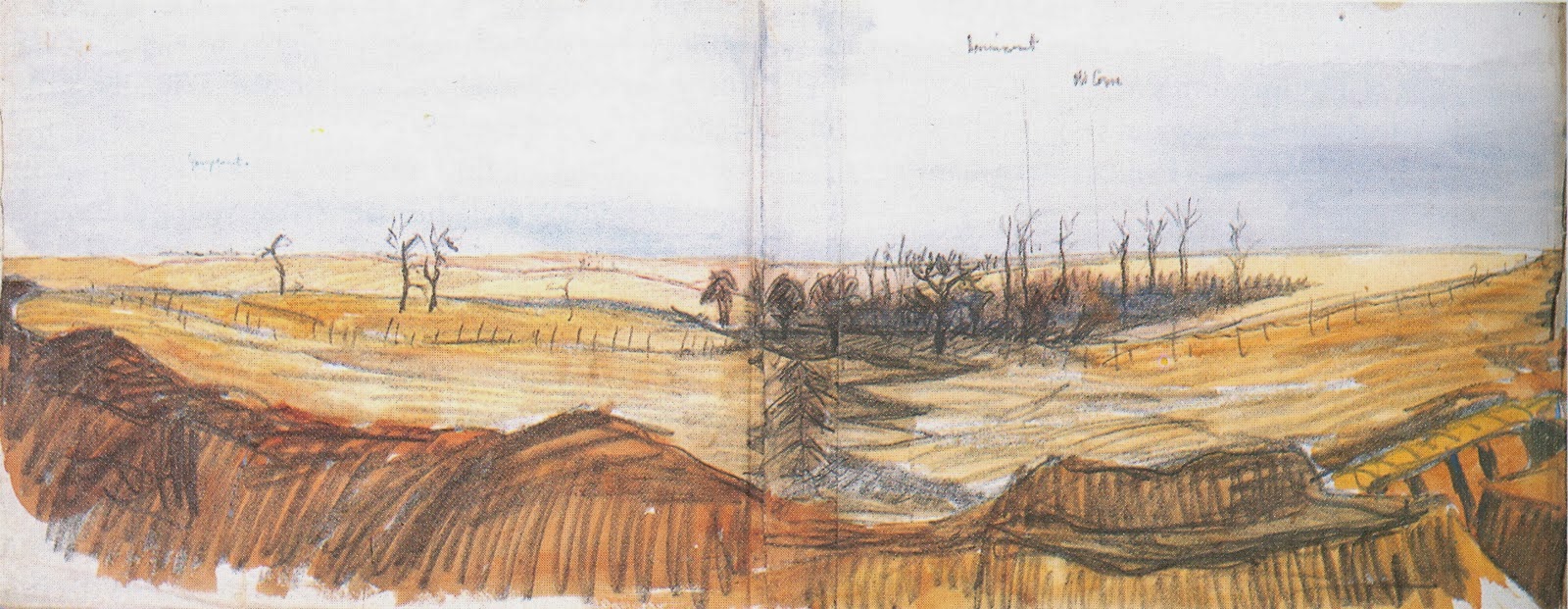

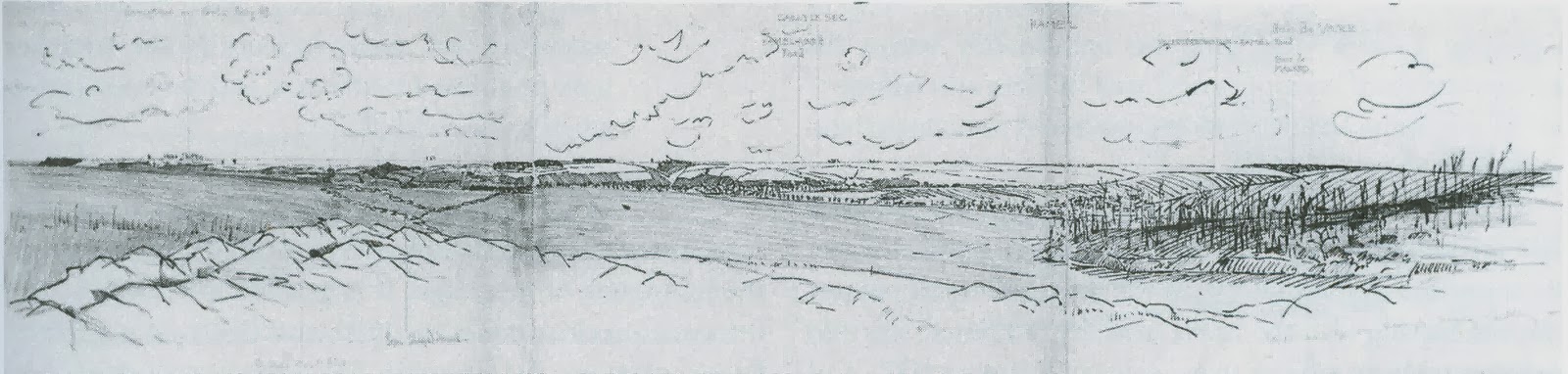

Fragments – New WWI Work

Latest Exhibition

I will be exhibiting with my wife, Addy Gardner, in Plymouth from 4th-26th April 2014. Some of the work I’ll be showing can be seen below.

Paul Maze (1887-1979)

An Unfinished World

First thoughts on Graham Sutherland, ‘An Unfinished World.’ Modern Art Oxford

|

| Graham Sutherland, Dark Hill – Landscape with Hedges and Fields, 1940. Swindon Museum and Art Gallery © Estate of Graham Sutherland |

In his excellent book, ‘A History of Ancient Britain,’ historian Neil Oliver writes:

“All of Britain was a work in progress as nature set about reclaiming the land. The period of hundreds of thousands of years known to archaeologists as the Palaeolithic – Lower, Middle and Upper – was over. The remote world of the mammoth-hunters of Paviland, even the lives and times of the Creswell artists and the butchers of Cheddar Gorge belonged to the past. The ice of the Big Freeze had drawn a line that separates them from us, then from now.”

This line in our history, this schism carved through time in much the same way as valleys were carved and gouged by ice from rock, is a place I find myself observing when I look at some of Sutherland’s haunted landscapes. They are silent spaces, from which it seems humankind is quite estranged; banished even. In some, it’s as if Man has yet to appear, as if the world is part of a parallel universe, similar in some respects, but altogether different. There are, as well as those landscapes which seem divorced from knowable time (from history), landscapes from the recent past; ruined prospects of towns wracked by war. And while the source of this ruination is Man himself, the sense which Sutherland creates is one in which Man again ceases to exist. It’s almost as if through both types of landscape (those we might – very loosley- describe as rural on the one hand, urban/industrial on the other), Sutherland is reminding us that for the unimaginably greater part of its existence, the world did not know us; that for the equally ‘impossible’ span of time that stretches ahead, the world will have no need of us either.

This sense of oblivion haunts Sutherland’s landscapes; Earth’s indifference towards us – in the grand scheme of things – permeates almost every canvas and drawing, no matter how small. They each seem to echo the wonderful words of the 17th century writer Sir Thomas Browne, when he writes in ‘Urn Burial.’

“We whose generations are ordained in this setting part of time, are providentially taken off from such imaginations. And being necessitated to eye the remaining particle of futurity, are naturally constituted unto thoughts of the next world, and cannot excusably decline the consideration of that duration, which maketh Pyramids pillars of snow, and all that’s past a moment.”

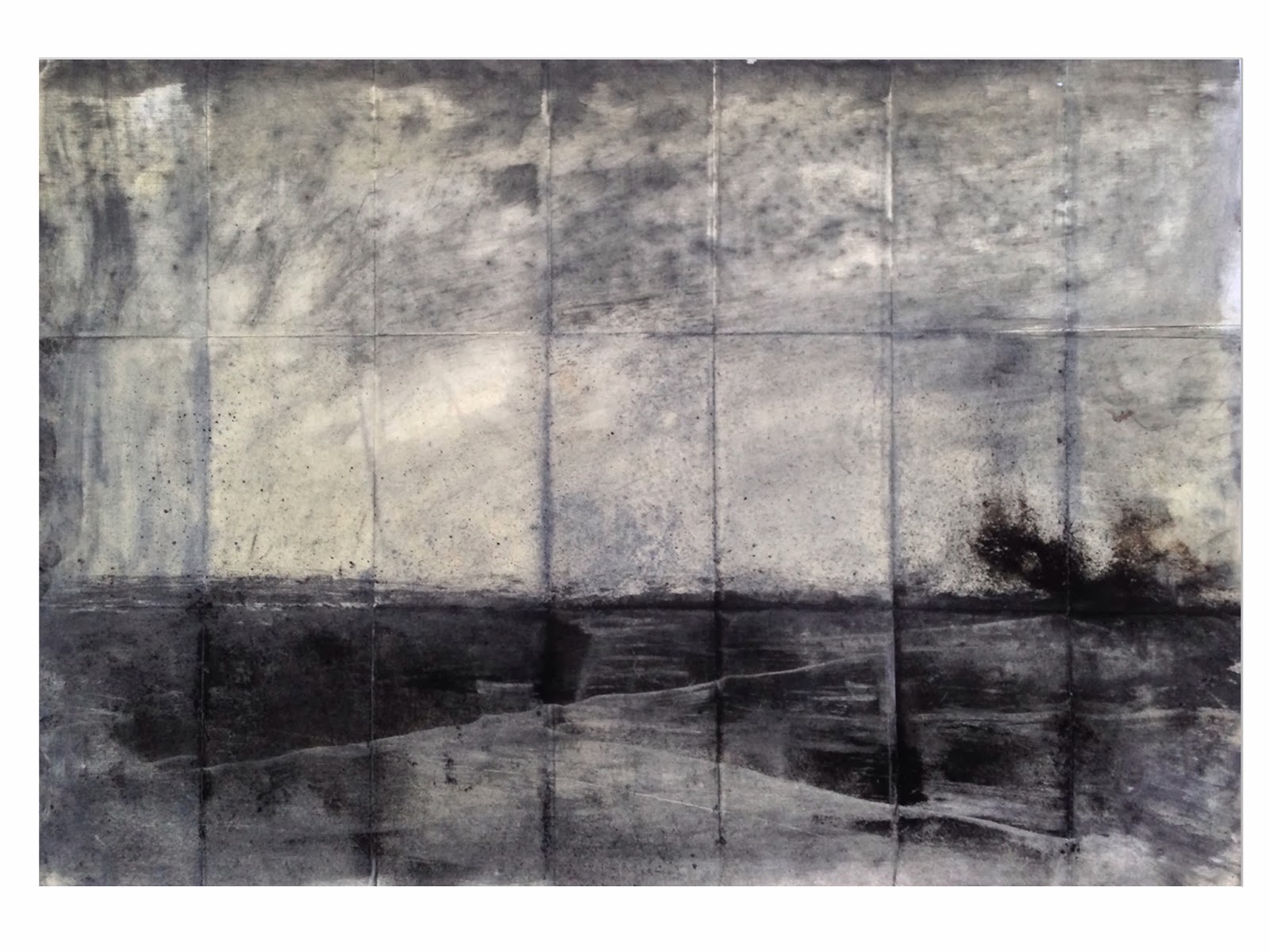

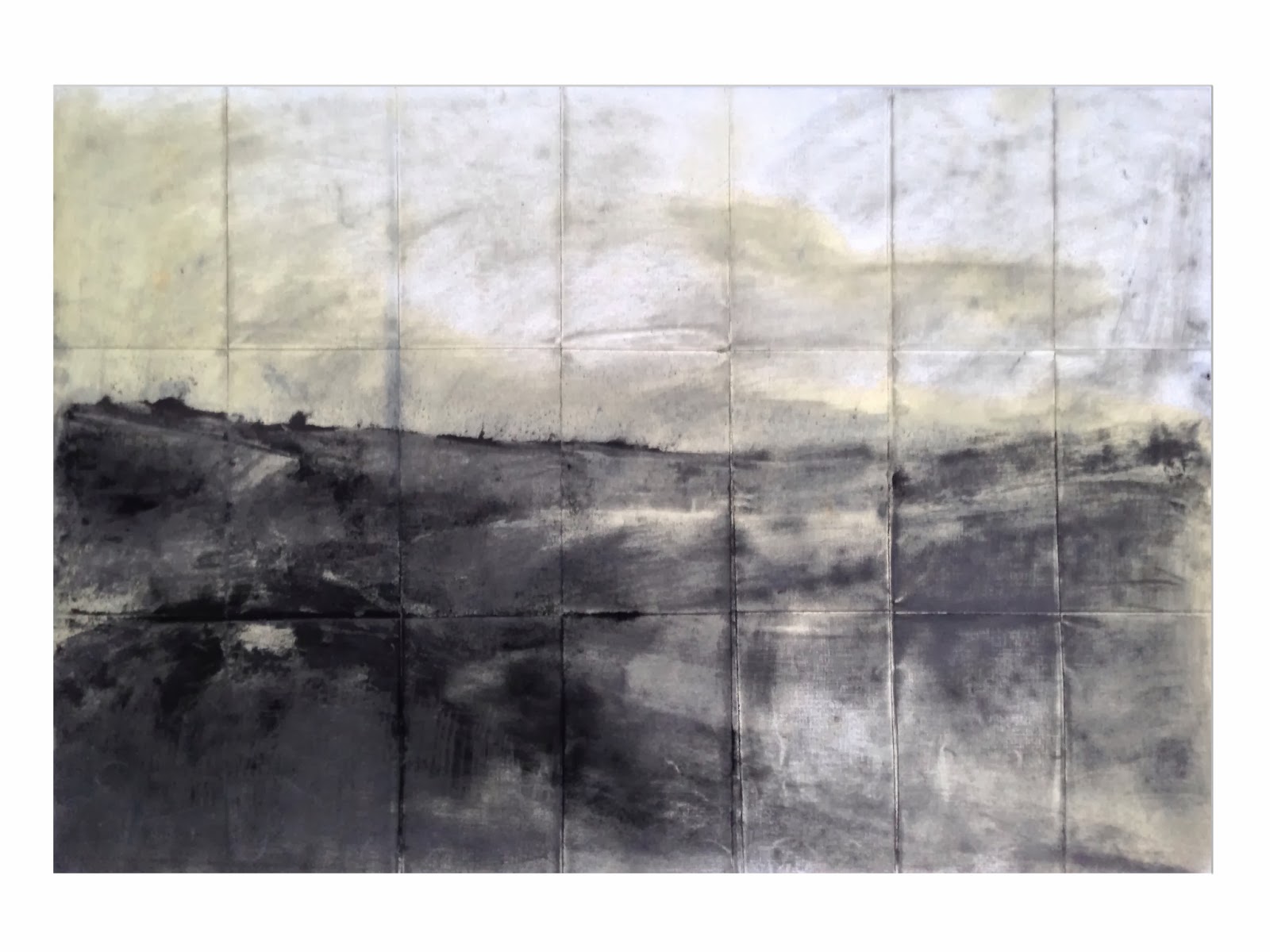

On some of Sutherland’s drawings, the artist has drawn a grid of horizontal, vertical and diagonal lines. Grids like these would often be used when scaling drawings up to full-size works, and perhaps that is what the artist intended them for. When I see them however, I see them not as something detached from the work itself – a mere tool for reproduction – but rather an integral part of the work. It’s as if the artist is trying either to order the chaos which he’s rendered on the page (and which he’s no doubt observed in the real world), or do battle with Man’s certain oblivion and relative obscurity, imposing his mark on the landscape; his dominion over the world.

|

| A Farmhouse in Wales 1940. Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales |

If the Farmhouse in Wales above is slowly dissolving back into the landscape, then perhaps it can be seen as a metaphor for man’s own ineveitable fate. The grid therefore, this means for scaling up, for seeing more clearly and in greater detail (the bigger picture as it were) is perhaps then a means for trying to understand that fate, for comprehending those ‘pillars of snow,’ so beautifully described by Browne in 1658.

|

| Welsh Landscape with Yellow Lane 1939-40. Private Collection, London |

In a video to accompany the exhibition, curator (and artist) George Shaw, describes how the use of yellow gives the appearance of a landscape which is jaundiced; perhaps sick. I however see this sickness not as a part of the landscape, but a part of our own vision of ourselves; our place in the ‘grand scheme of things.’ Even where Sutherland has painted machines (which by their very existence would seem to point towards the existence – and therefore relevance – of mankind), there is still the sense of Man’s complete absence from the world. It’s as if, as I’ve said, these paintings depict those two great and awful spans of time, between which Man’s existence is pressed, like rocks beneath the vast sheets of ice, which once crawled and covered this place we call home. (Even those gargantuan glaciers – in places almost a mile thick – which smothered the country for so many thousands of years, would seem like Browne’s ‘pillars of snow’ when considered against the backdrop of eternity.)

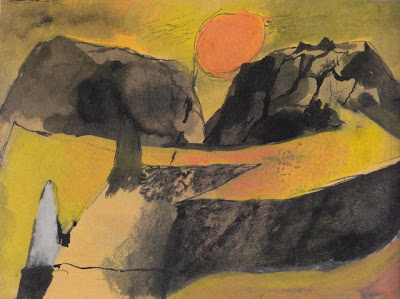

In the exhibition’s first few paintings, we find these same desolate landscapes, replete with standing stones (for example, in ‘Sun Setting Between Hills’ below) such as those found at ancient sites throughout the country.

|

| Sun Setting Between Hills 1937. Private Collection |

At once these landscapes become charged with mystery, and like those paintings which show, for example, cranes gorging themselves on the landscape, we are presented with evidence of Man’s existence. The standing stone and the ruined urban landscape, mirror one another. Poles apart, they seem to delineate this landscape in which we, for a short time, have strutted the stage of our existence. No-one is likely to walk the yellow roads which cut through the world above – yet someone must have been there.

|

| Interlocking Tree Form 1943. The Whitworth Gallery, University of Manchester |

Despite this apparent absence of Man, the trees in some of Sutherland’s landscapes seem almost human, at least in their gestures. Some such gestures echo the agonies of Picasso’s ‘Guernica’, (for example, in ‘Interlocking Tree Form’ above) while ‘Study for a Blasted Tree,’ calls to mind Goya’s ‘Disasters of War.’

|

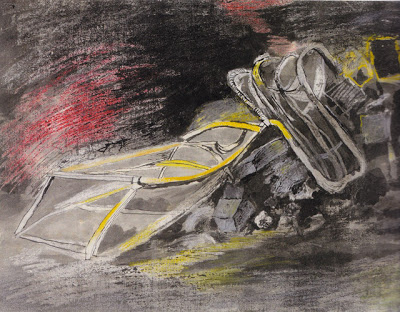

| Fallen Lift Shaft 1941. Junior Common Room Art Collection, New College. |

It was whilst looking at the painting above, that I found myself thinking of William Blake. In this work, ‘Fallen Lift Shaft,’ there is a small patch of red which is reminiscent of some of the poet’s own paintings. The lift is on the one hand a casualty of war, a victim of Man’s aggression. On the other it’s a symbol of his descent. It is perhaps the Fallen Angel.

The exhibition is titled ‘An Unfinished World‘ and whilst reading Richard Dawkins’ book ‘The Ancestor’s Tale,’ I found a quote, which for me encapulsates what that title means. The world, with or without Man, is always unfinished. Dawkins writes:

“The second connected temptation is the vanity of the present: of seeing the past as aimed at our own time, as though the characters in history’s play had nothing better to do with their lives than fore-shadow us.”

In other words, we are not the end, just as we weren’t the beginning. And it’s this conceit which Browne cautions against in his meditation on death discussed above. Sutherland’s landscapes are for me, the equivalent of trying to imagine one’s own non-existence in a world which is always, as Neil Oliver writes, ‘a work in progress,’ one in which nature will one day set about reclaiming from Man.

One might think it’s possible therefore to view Sutherland’s paintings as a warning against this conceit. But to do this is in itself a kind of conceit. The fact is, we are just another part of the landscape. The yellow road was there before us, and after us the yellow road rolls on. Sutherland’s paintings are not warnings, but statements of fact.

And while this might sound somewhat depressing, another quote from Dawkins (again from ‘The Ancestor’s Tale’) might just lift our spirits:

“As physicists have pointed out, it is no accident that we see stars in our sky, for stars are a necessary part of any universe capable of generating us. Again, this does not imply that stars exist in order to make us. It is just that without stars there would be no atoms heavier than lithium in the periodic table, and a chemistry of only three elements is too impoverished to support life. Seeing is the kind of activity that can go on only in the kind of universe where what you see is stars.”

|

| Landscape 1969. Harry Moore-Gwyn (Moore-Gwyn Fine Art) |

In many of Sutherland’s works, our very own star, the sun, is present such as in the work above. In one of the first paintings within the exhibition, to the last (painted just four years before his death- see below) the same sun is in view.

|

| Twisting Roads 1976. Private Collection. |

And we – like Sutherland – can only see it, we only know it, because we exist.

Perhaps therefore, in Sutherland’s work, humankind is in evidence after all.

Sculpture

I am not, at least as far as I’m aware, a sculptor, but I think that what I’m striving to articulate in my work has perhaps more to do with sculpture than anything else. The following statements, from the book ‘Figuring it Out,’ by archaeologist Colin Renfrew were made by the sculptor Antony Gormley.

“I want to confront existence. It is obviously going to mean more if I use my own body… I turn to the body in an attempt to find a language that will transcend the limitations of race, creed and language, but which will be about the rootedness of identity… The body is a moving sensor. I want the body to be a sensing mechanism, so your response to the work does not have to be pre-informed and does not necessarily encourage discourse… If my subject is being, somehow I have to manage to engage the whole being of the viewer.”

“My body contains all possibilities. What I am working towards is a total identification of all existence with my point of contact with the material world: my body… Part of my work is to give back immanence both to the body and art.”

The last sentence particularly resonates with me, for part of the purpose of my work is I think to give back immanence to the past and to history, something which I have come to realise can only come about through the immanence of the body – the ‘moving sensor,’ which I have otherwise described as being like the recording/playback head of a tape player.

We are all familiar with the body-casts of Pompeii; men, women and children frozen at the moment of their death almost 2000 years ago. Buried in ash, the spaces which had once contained their bodies remained after the bodies had decomposed, allowing archaeologists, to use them as moulds by pouring plaster into the cavities. It was whilst reading about the casts in Colin Renfrew’s book ‘Figuring it Out’ that I began to think of the process of casting in terms of what I’ve been researching these past few years.

If we stand in a place, for example a wood, we can try to imagine those who’ve been there before us. By being aware of the moment of our own experience, of the wind, the light, the sound of the trees and so on, we can try to see the past through the immanent lens of the present. In a previous entry ‘An Archaeology of the Moment,’ I mentioned the writing of Christopher Tilley and the concept of Other and whilst reading Colin Renfrew’s book I realised how the process of creating the casts in Pompeii shared something with what I’ve been researching, albeit metaphorically.

If we stand in a place, we are defined not only by the shape of our bodies (our physiognomy), but by everything around us. To recap, as Tilley writes: “The painter sees the tree and the trees see the painter… in a manner comparable to that in which the mirror ‘sees’ the painter: that is, the trees, like the mirror, let him become visible: they define a point of view on him which renders visible for him something that otherwise would remain invisible – his outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence… The trees and mirror function as Other.”

Just as the trees function as ‘Other’ therefore, so must the sun, the stars, the clouds, hills, mountains, the sea, rivers, the wind, the rain and so on.

Imagine that all these things, in the place where once someone stood are – metaphorically speaking – like the ash of Pompeii, in that the shape of the person’s body is somehow sculpted by them. Of course this shape is fleeting, but imagine again that it remains, delineated by the world around it. In order to ‘see’ the shape, we must learn to fill it, not, of course, with plaster but with our own bodies or rather our presence.

At any given moment, we are sculpted by the world around us. We are both looking for and filling in the gaps left by others. We are therefore artists, artwork and viewer simultaneously.

Imagine these two situations: One, you are standing in a gallery in front of a landscape painting, a picture of a wood with no-one in it. Two, you are standing on a path in a wood that is empty and in this wood, the trees and the wind blowing through the branches, the feel of your feet upon the ground, the sound of the birds, the dappled light and shadows all act as ‘Other’ rendering your outside – your presence – visible. The gallery too is empty, but like the wood, you are far from alone, for just as the painting also acts as ‘Other’ in terms of rendering your presence visible, so the spaces left by those ‘rendered’ before are made visible again by your presence; not least the space left by the artist. And after the artist come the spaces left by everyone who’s seen the painting before you, and in the woods the same is true; although there maybe no-one else on the path, the spaces left by everyone who’s ever walked upon it are filled with your presence; the present fills the spaces of the past.

Having found Antony Gormley’s words so interesting, I read the transcript of an interview between himself (AG) and Ernst Gombrich (EG). The following are sections which I found to be particularly pertinent.

AG I want to start where language ends.

EG But you want in a sense to make me feel what you feel.

AG But I also want you to feel what you feel. I want the works to be reflexive. So it isn’t simply an embodiment of a feeling I once had.

EG It’s not the communication.

AG I think it is a communication, but it is a meeting of two lives.

In many respects this conversation above reflects precisely what I am trying to do: to feel the way people felt in the past by feeling what I myself am feeling. It is the meeting of two lives.

AG I would be interested to know whether you feel that it is possible to convey a notion of embodiment without mimesis, without having to describe , for instance, movement or exact physiognomy?

EG I have no doubt that not only is it possible but it happens in our response to mountains, for example, we lend them our bodies.

–

AG I can’t be inside anyone else’s body so it’s very important that I use my own. And each piece comes from a unique moment in time. The process is simply the vehicle by which the event is captured, but it is very important to me that it’s my body.

–

AG I am interested in something that one could call the collective subjective. I really like the idea that if something is intensely felt by one individual that intensity can be felt, even if the precise cause of the intensity is not recognised. I think that is to do with the equation I am trying to make between an individual, highly personal experience and the very objective thing – a thing in the world amongst other things.

–

AG Then I go into the second stage which is making a journey from this very particularised moment to a more universal one.

–

As I’ve written before: In a famous definition of the Metaphysical poets (a group of 17th century British poets including John Donne), Georg Lukács, philosopher and literary critic, described their common trait of ‘looking beyond the palpable’ whilst ‘attempting to erase one’s own image from the mirror in front so that it should reflect the not-now and not-here.’ Thinking in terms of the metaphor I have described above (the trees and mirror function as Other), we could say that this erasing of one’s image is an attempt to see the space left behind us. I have also written in the past how history necessitates the consideration of our own non-existence; this space also reflects that state.

53rd Venice Biennale

In terms of individual participants showing at the Biennale, I was taken with quite a number of works including Nathalie Djurberg’s disturbing video/sculpture installation described in the catalogue as a surrealistic Garden of Eden, Hans-Peter Feldmann’s beautiful Schattenspiel (Shadow Play), Simon Starling’s Willhelm Noack oHG and Chu Yun’s Constellation. There were numerous others too, including, perhaps most notably Mona Hatoum who showed at a so-called ‘collateral event’ in the Querini Stampalia.

But just as there are a small number of winners so there’s an inverse number of losers – crap to you and me. The winner of the wooden spoon however has to be Switzerland’s entry (I’m fighting against the desire to write Bang-a-Bang-a-Bang or such like silly song title and have in a sense already failed). The work explained – or rather the blurb did – that ‘drawing is a movement of sight, of the nuanced shifts and deviations that attract undirected attention to objects and dream figments that are never really concretized’ and from that codswallop you might agree the curators or whosoever wrote the guff for each piece should also claim a piece of the booby-prize. Other notable rubbish included Australia (who were also rubbish two years ago) and Germany (who were my wooden spoon winners at the last Biennale and who for this year’s effort drew on the talents of British Artist Liam Gillick (?) who managed to make a trip to IKEA look interesting – by the way I read that Gillick travelled for more than a year, ‘researching and developing his project for the German pavilion in a continuous dialogue with curator Nicolaus Schafhausen’ – quite how he arrived at making some dull cupboards escapes me). Israel’s entry was terrible and Norway’s too (definitely nil point). There were other notable wastes of space but I can’t be bothered to waste any space upon them.

One of the biggest disappointments for me however was the British entry from Steve McQueen, whose film Giardini was, well, boring. Certainly it contained some beautiful shots and was an interesting idea, but at 30 minutes it was just too long. There was also the fact that one had to view it at a certain time, that viewers were asked to arrive 10 minutes before the show which built up expectations to such a level the film almost had to fail. After a few minutes we were already shuffling in our seats, a few more minutes – when the dogs came again and sniffed around in a manner straight from a Peter Greenway film (no slight on that director intended) – and we were checking our watches. As a piece one could view at leisure, walking in and out at whatever time suited, it probably would have worked, but treating it like a film turned it I’m afraid into a very dull affair. As I don’t have any pictures of these less-than-inspiring works here is a picture of very-inspiring Venice.

What I really loathe are those pieces where the artist assembles tons of stuff in a room or space with which the viewer is asked to ‘create a narrative’ or not as the case may be. There are a few exceptions where this type of work is successful, but by and large it irritates the hell out of me. So Haegue Yang and Pascale Marthine Tayou, pack it in now.

But what about the winners..?

For me, Peter Forgacs’ Col Tempo was exceptional, giving history a human face. Taking archive footage from the Wastl project, he showed how people in the past, who lived in times of trauma were just like people today. It sounds a pretty obvious thing to say but often when we think about the past we tend not to see individuals as such, but rather numbers and tropes. Ironically, the footage Forgacs used was originally concerned with anything but the individual, rather Dr Josef Wastl, head of the Department of Anthropology at the Museum of Natural History in Vienna, put on an exhibition which attempted to present to the public ‘the characteristic physical features’ and ‘mental traits’ of the Jews. What we see when looking at the images however are individuals just like us today.

Poland’s Krzysztof Wodiczko examined the issue of immigration. The Guests of the title were shown as shadow-figures outside the space in which we as onlookers (or out-lookers) were standing. We saw them without faces, without distinguishable characteristics, save for their voices which accompanied the work Nevertheless, in their outlines we could recognise the people we see all around us, the way they move, the way they stand and taken together with Forgacs’ work, it was indeed a powerful piece (by the way Poland won it for me two years ago).

Another powerful pieces came via Teresa Margolles who showed her work in the Mexican ‘Pavilion’. Her installation (and action) What Else Could We Talk About? took the country’s endemic violence and brought it into the Palazzo Rota-Ivancich. The Palazzo is a decaying structure which is nonetheless quite beautiful. The original (or at least very old) decor is still visible – faded wallpaper with patches where paintings (perhaps portraits given their shape) once hung. It was almost enough just to be in the building. Each room contained an incongruous mop and plastic bucket in which we learned blood collected from sites of killings in Mexico was mixed with water and used to wash down floors over which we were walking. In every room therefore one could sense quite palpably the echoes of missing people – those who’d lived and died in the city over the course of the Palazzo’s existence and those who lived and died in the present albeit thousands of miles away. There was a sense of the past and distance in the present being synonymous. There were also paintings again made from blood collected at the sites of executions in Mexico. Each painting, hanging like a blanket, resembled a modern-day Turin Shroud and I found myself being asked to believe, not in a life that could be known only through death, but individual deaths (and many of them) happening in the midst of life today.

Estonia’s entry examined in part the power of symbols and in particular the replica of a statue which had once stood in the capital Talinn. The statue (the replica of which looked quite kitsch in the gallery) marked the grave of Red Army soldiers from 1947 until its removal in a post-communist Estonia. For most Estonians the statue was a symbol of Soviet oppression, for many ethnic Russians it symbolised victory over Nazism. The artist, Kristina Norman placed the replica where the original statue had stood and documented the furore that followed with the police taking both her and the statue away.

The Portuguese artists Joao Maria Gusmao and Pedro Paivia showed a series of video projections in a piece entitled Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air. Each piece appeared to have been shot with a high speed camera, revealing in slow motion clear details of fire, water etc. But the appearance of each projection was that of a 1970s snapshot. The texture and quality of the projections reminded me of my own holiday photographs and in particular some work I’ve been doing on their hidden details.

And finally Luxembourg. Another video installation tucked away in a backstreet in which the artists Gast Bouschet and Nadine Hilbert reflected on the divide between Africa and Europe, evoking according to the catalogue issues of difference and immigration. What I liked about the piece was the dialogue created between the various projections as seen through open doorways between the rooms. The image of a fly struggling in a spider’s web and that of a man standing still in a street but clearly lost in an alien world was particularly striking – one could sense via the other image his internal struggle.

All in all the Biennale served up the usual mix of both the sublime and the ridiculous. Much of it – especially in the Arsenale (now a much bigger site) was pretty lame, but then any work would struggle in such a massive space, vying for attention like an antique thimble in a flea-market. Certainly the use of spaces outside the sites of the Giardini and Arsenale tended to make for more interesting work, but one could argue that when in a place like Venice every space and every part of every space is interesting, whether home to art or not.