The image below shows (on the left) an earlier work about Belzec (1 to the power of 500,000) from 2010, and on the right, what would be a video (using the same number of squares) derived from the video filmed at Belzec in 1999.

Belzec Video: Snow 5

The same idea as before applied to footage of trees at Belzec. The number of squares used is the same as an earlier work.

Belzec Video: Snow 4

Video version of that described in the previous entry regarding this project.

Belzec Video: Snow 3

What interests me about the video footage from the archaeological dig at Belzec (1999) is the sense of colour and movement. Often, when one is researching the Holocaust and sites like Belzec, most of the imagery one encounters is black and white and often still (although of course there is a great deal of moving footage as well).

As I’ve said, it’s difficult, given the quality of the footage, to make anything that would resemble a narrative of the investigation carried out there. So taking the idea of colour and movement as something I wanted to work with, I decided to process the video and to use a mosaic filter to reduce the image to pure forms.

When I was an undergraduate in the early 1990s, I produced a series of paintings based on this idea in a work entitled ‘A Single Death is a Tragedy, a Million Deaths is a Statistic.’ I was looking at the idea of anonymity and the past as anonymous (something which I’m still looking at today) reducing the image of a man, through a series of canvases to a single coloured pixel.

One of the ways of understanding an event as horrific as the Holocaust on an empathetic level (as far as is possible) is through understanding that the past was once the present that what happened in places such as Belzec happened when the past was now. When I sit here now and look out the window, I see the trees move, I see their colours, I see the sky, the clouds drifting and so on. I see movement and colour.

Whenever I look at images of the past, especially those in black and white, I try to imagine the scene as if it was now. I colour it, I imagine what happened immediately after the shutter was released. The smallest details become especially important. When I myself visited Belzec in 2007, I was aware of the world moving all around me, of the trees especially; of the sounds they made and the colour. Putting this together with what I knew had happened there, enabled me in some small way to empathise with those who died.

The stills below are taken from the processed video and even though they reduce the place to pixels (and therefore render it anonymous) there is something about the individual squares of colour which serve somehow to represent both the anonymous individual and the nownes of the present.

Belzec Video: Snow 2

Edited footage shot in 1999 at the site of the former Belzec Death Camp in Poland. The footage is of very poor quality and as an artist, I’m looking at how it might be used in my own work.

Belzec Video: Snow

About two years ago I was given recordings of an archaeological investigation at the site of the Belzec Death Camp in Poland (1999). These investigations were carried out prior to the construction of the memorial there and my task was to edit the videos into something that could be seen as a narrative of those events.

The videos however were less than brilliant and any documentary-type video was going to prove impossible. However, I wanted to work with the video in some way or another and in 2010, as part of Holocaust Memorial Day, I exhibited a number of images based in part on the original video.

This year, I want to make a piece based on the video and the stills I exhibited in 2010. The initial idea is to capture all the pieces of ‘snow’ from the recordings and to arrange them in a sequence. The ‘snow’ represents the end of something, and it’s the idea of something ending which interests me as regards this piece.

Eventually I will develop the video using the colour/documentary footage on the tapes, intercutting them with the ‘snow’ elements. I will put up extracts of each stage as and when they’re complete.

Below is a short extract of the snow sequence.

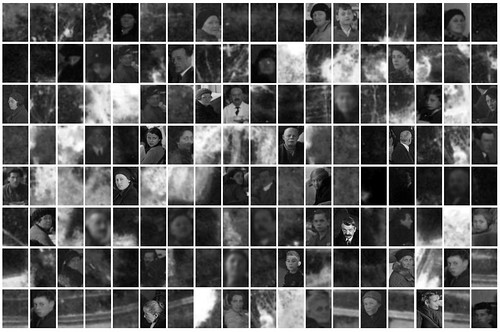

A Well Staring at the Sky

The title of this piece takes its name from a passage in Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet;

“We never know self-realization. We are two abysses – a well staring at the sky.”

For me, this quote describes the act of looking at a photograph, at people in the past who are likely no longer with us. I look at them from a time when they do not exist, and they look at me from a time when my existence was wholly unlikely. They are reflections left in the water of the well, and I, for the moment am the person looking in. The portraits in the work are from a single photograph taken in Vienna c.1938. The faces are mixed with images cropped from an aerial view of the Bełżec Death Camp photographed in 1944. History too is a well staring at the sky. Again in the well’s water, we see the sky reflected with some of its stars and all of its gaps. But no gap is truly empty and all the holes in what we call history are full of traces; the residue of a glance perhaps shared between two people.

To see more work from this exhibition, please follow this link.

Poland

I’ve just returned from another fantastic trip to Poland, this time taking in the east of the country through Lublin, Zamosc and the very picturesque Kazimierz Dolny. My girlfriend negotiated the less-than-brilliant Polish roads whilst I sat in the passenger seat armed with my GPS creating a record of the route. The weather was wonderful, over 30 degrees every day and very sunny.

One of the reasons for the trip, aside from it being a holiday, was to visit two more Holocaust sites, these being the concentration camp at Majdanek and the death camp at Belzec. Having left Warsaw we made our way down to Lublin and on arrival, went to the Majdanek concentration camp, just on the outskirts of the city. I didn’t know much about this camp and even after reading a little about its history I didn’t expect what we found there. It is one of the best preserved camps in the country and in some respects is like a smaller version of Auschwitz and Birkenau in one. Like Auschwitz it has numerous exhibitions in each of the barracks, including piles and piles of old shoes. Yet whereas in Auschwitz these were held behind glass, here in Majdanek they are stored in cages; one can smell them.

The gas chambers are still intact here along with the original washrooms, and walking through these was, as one would expect, particularly poignant. We noticed on the walls and ceilings of the chamber, that there were patches of blue. I assumed this was just mould caused by damp, but on returning home, I’ve since discovered these patches were caused by the residue of the Zyklon B gas. Indeed, one can see how dense the colours are on the ground and almost see the residue pale as it climbs the walls.

Colours have become a point of interest for me in my work. As above, the blueish tones on the grey walls were striking, not only because of their colour, but because of what they signified. The same was true in the barracks full of shoes. Amidst the rows of earth-brown shoes, one could occasionally glimpse a patch of colour, a red shoe (below) or a blue one.

Another striking part of the camp was the memorial containing a mound of ash; the cremated remains of the camp’s thousands of victims. It’s hard to imagine this mass of ash was once a mass of people.

Lublin itself was very interesting. The city has a wonderful old town which more than hints at its original splendor. Sadly, some of the old houses are in a terrible state and one was left wondering whether they would survive.

Having spent the evening in the city, we had an good breakfast and made our way to Zamosc, a sixteenth century version of Milton Keynes, founded by Jan Zamoyski and built from scratch by the Italian architect Bernardo Morando in 1580. However, before sampling its various delights, we visited the second Holocaust site on our itinerary – the site of Belzec Death Camp.

Driving through the village of Belzec, it was hard to tell exactly where the camp was; to be honest, neither of us knew quite what to expect. And whereas before, in the camp at Majdanek we found patches of colour in amidst the piles of shoes, so here in Belzec, as we drove down the road, we saw a shadow in amidst the countryside; a charcoal scar like a field ravaged by fire. This was it, and it took our breaths away.

Whereas the proximity of Majdanek to the centre of Lublin was shocking, here at Belzec, what was shocking was its size. Measuring just 275 metres on three of its sides and 265 on the other, this small space witnessed the deaths of around half a million people, all in the space of nine terrible months. But unlike camps such as Majdanek, Auschwitz and Auschwitz-Birkenau, nothing of this camp (which was liquidated by the Germans in December 1942) remains.

I must admit I wasn’t sure how I’d respond to visiting a place where nothing of the original camp remained, but of course what is important here is the land itself, for it’s the very soil upon which the victims walked and within which they were buried which holds their memories still. The scale of the site becomes the memorial and just as its countless victims walked upon this small piece of land to their deaths, so we walk around it, looking in, so as to remember them, staring at the rocks which litter the landscape as if each stone is a single individual.

Thinking about the hundreds of thousands of stones, I’ve been reminded since coming home of an old Jewish cemetery we visited in Kazimierz Dolny which was desecrated and destroyed by the Nazis. We wondered when we visited it about the practice of putting stones on graves and I have discovered that when the tradition started grave monuments were mounds of stones; visitors added stones to the mound to show we are never finished building the monument to the deceased. Another explanation was that it shows those visiting that others have come before to remember. The monument at Belzec therefore, covered as it is with hundreds of thousands of stones reminds us that this piece of land is a grave for hundreds of thousands of people who will not be forgotten; the memorial will never be finished. The fact that the stones look like the remnants of a demolished building is also significant.

Walking is itself a vital part of the memorial (it will never be finished as it is incomplete without people there to walk around), just as it has been important to me in my work on Belzec prior to my visit. I’m wondering now if stones will also become a feature?

One of the most haunting parts of the memorial was the walk through the tunnel, a cutting made into the hill exposing the soil on both sides.

This brought to mind two things: one, the ‘tunnel’ through which the victims walked to the gas chambers, and secondly, the fact that we could see inside the ground, into the very place in which the victims had been buried.

From here we made our way to Zamosc and having spent a lovely night there, made our way to Kazimierz Dolny via the beautiful Kozlowka Palace, Zwierzyniec and the spa town of Nalenczow. Looking at the towns we passed through (including Zamosc which we left), one couldn’t help remember those very names as being places from which Jews had been deported to Belzec; the day before was never far from our thoughts.

Kazimierz was indeed a beautiful little town which had suffered much under the Nazi terror; half its population had been deported to camps such as Belzec. The weather was hot and having rested for the night, we spent the next day walking around the town, visiting King Kazimierz’s castle and walking through the forests by which it was surrounded. The landscape was indeed beautiful.

It was near the end of the day that we came upon the old Jewish cemetery, destroyed by the Nazis. After the war, a memorial was built using the old gravestones which again served to remind us of a recent and tragic past.

Walking

As part of my continuing work on sites of the Holocaust, I have been investigating Belzec death camp which I will be visiting next month. Even with a place as large as Auschwitz-Birkenau, it’s hard to equate its size with the number of people killed there (1.1 million). Yet this appalling correlation of camp size to victims, is perhaps at its most disturbing in Belzec, where in a space of less than 300 metres by 300 metres, approximately 600,000 people perished. Death on this scale, on the open fields of battle is hard enough to imagine, yet it somehow seems all the more sickening in a place the size of Belzec (and one designed for the purpose). In order to ascertain just how big (or rather small) 300m x 300m is, I bought a pedometer and looked for somewhere in Oxford which might, more or less, equate with these dimensions. The closest I got to those dimensions was in Christ Church Meadow, which if anything was bigger. As I’ve already documented my continuing investigations on this subject I won’t add any more here, but I would like to explore further the idea of using the memory of a place to understand the wider past; something which I touched on in Postcards.

During my walks, I found myself recalling a raft of memories from my own past, triggered by the sites I saw as I travelled. Even a short walk around Christ Church Meadow (the length of which, in terms of time, was itself indicative of the horror and magnitude of the suffering at Belzec) opened the floodgates, not only for my own memories to pour through, but those of the city itself . Here I was, an individual with my own recollections, walking amongst the hundreds of thousands of memories of people long since dead from which the city is inevitably constructed – an interesting metaphor for the individual swallowed by the world stage; swallowed by the violence war.

As I have already written, but something it’s worth stating again, the Italian author Italo Calvino discusses memory and its relationship to a place in his book Invisible Cities. The city he says, consists of:

“…relationships between the measurements of its space and the events of its past; the height of a lamppost and the distance from the ground of a hanged usurper’s swaying feet; the line strung from the lamppost to the railing opposite and the festoons that decorate the course of the queen’s nuptial procession; the height of that railing and the leap of the adulterer who climbed over it at dawn; the tilt of a guttering and a cat’s progress along it as he slips into the same window; the firing range of a gunboat which has suddenly appeared beyond the cape and the bomb that destroys the guttering; the rips in the fish net and the three old men seated on the dock mending nets and telling each other for the hundredth time the story of the gunboat of the usurper, who some say was the queen’s illegitimate son, abandoned in his swaddling clothes there on the dock…”

Could it also be said, that there is a relationship between the measurement of spaces within the city and the events of the past elsewhere?

Maps and Walking

The main theme of much of my work has so far been the Holocaust and in particular its sites, such as those at Auschwitz-Birkenau, Belzec and Babi Yar. I’ve also been studying memory and how memories within objects and buildings might allow us a glimpse of the past; a theme which has fascinated me ever since I was a child. It was through reading Bill Viola’s writings a few months back that I was reminded of the mnemonic techniques practiced by the ancient Greeks:

“The idea of art as a kind of diagram has for the most part not made it down from the Middle Ages into modern European Consciousness. The Renaissance was the turning point… The structural aspect of art, and the idea of a ‘data-space’ was preserved through the Renaissance however in the continued relations between image and architecture. Painting became an architectural, spatial form which the viewer experienced by physically walking through it. The older concept of an idea and an image architecture, a memory ‘place’ like the mnemonic temples of the Greeks is carried through in the great European cathedrals and palaces, as is the relation between memory, spatial movement and storage (recording) of ideas.”

When I first read this quote, I was at the time researching The University Parks in Oxford, and in particular examining the plaques on the benches. I realised then, that my act of walking and ‘remembering’ those who have passed away, was in a broad and rather loose sense, like walking through one of those ‘mnemonic temples’ albeit in a physical sense. I was constructing a bigger picture of the place.

More recently, walking has started to play an important role in my work on the Holocaust (one of the themes which has struck me through my research has been that of walking. Many photos of the Holocaust show people walking, usually, and tragically, to their deaths). I’ve started to look at the Operation Reinhard camps and in particular Belzec. Laurence Rees, in his book, ‘Auschwitz’, describes the unimaginable scale of death and contrasts it with the disproportionately tiny size of Belzec Death Camp, which measured less less than 300m x 300m. I knew this was a small size, but it wasn’t until I walked around some familiar spaces in Oxford – including the University Parks – that I realised just how small it was.

Since then I’ve started looking for more evidence of the size of Belzec (and other camps) so that I might walk specific distances around the city, and have since discovered a number of maps drawn by survivors, SS men and archaeologists. These roughly sketched maps, these ‘memories,’ are a poignant reminder of the camp’s existence and might help me in my attempts to bring people closer to the Holocaust, which should never be forgotten.

“All things fade away in time, but time itself is made fadeless and undying by recollection.” Apollonius of Tyana

“We have to describe and to explain a building the upper story of which was erected in the nineteenth century; the ground-floor dates from the sixteenth century, and a careful examination of the masonry discloses the fact that it was reconstructed from a dwelling-tower of the eleventh century. In the cellar we discover Roman foundation walls, and under the cellar a filled-in cave, in the floor of which stone tool are found and remnants of glacial fauna is the layers below… Not only our memories, but the things we have forgotten are ‘housed’.” C.G. Jung

“Memory, whether individual or generational, political or public is always more than the prison house of the past.” Andreas Huyssen

Here I must return to the ancient Greeks and their mnenomic temples. With a place or loci, such as a house, fixed in the mind, the person remembering would place various objects in its rooms (“…what I have spoken of as being done in a house can also be done in public buildings, or on a long journey, or going through a city…”), objects which by association would remind them of part of the whole thing – such as a speech – to be remembered. Here I saw at once a correlation with my work on Belzec. The ancient Greeks were walking as a means of remembering, of not forgetting; their memory loci were in effect maps which one could sketch, maps of the mind. Therefore, the maps drawn by survivors, are in effect maps of their minds and bring us closer to the horrors of the time – closer to the individuals who suffered.

The fact that objects were used to create associations, and therefore build (through ‘walking’) a bigger ‘picture’ of something also fits in with the recent work I’ve been doing on Auschwitz, looking at the possessions left by the victims and trying to build a picture of the individuals before the Holocaust, to see them not only as victims, but people who lived lives before its horror.

Through walking distances which I’ve taken from descriptions of the camp, I have found myself walking back into my own past and the past of the city in general; for example, walking the route of Cuckoo Lane and the Old London Road at Shotover. My own past confirms my individuality and the past of the city confirms my place as a small part in the mass of memories associated with this place (this also correlates with my work on Auschwitz, trying to find the individuals amongst the huge number of dead, individual possessions from amongst the mountains, names rather than inconceivable numbers). The fact these walks have been derived from a map or a description of Belzec, helps me to identify further with the individuals who suffered there; not because I can in anyway conceive of their suffering – no-one could ever imagine the horrors they endured – but because I can imagine their own pasts and that of the places they knew so well, places from which they were taken to their deaths.