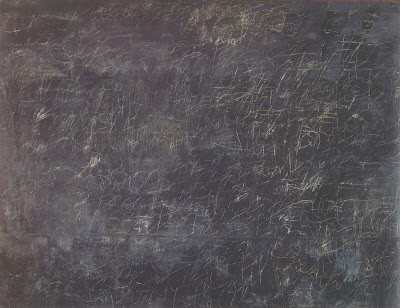

The first painting I have chosen is Cy Twombly’s 1955 painting Panorama.

The first thing to say about discussing a work of art which one has only seen in a book, is that any view is going to be extremely restricted. To be fully appreciated, art (whether paintings, installations, sculpture and so on) needs to be experienced. The impact of a painting can be felt as much with the body as the eyes, and a reproduction found in a book will only reveal a fraction of its ‘story’. (I never cease to be amazed – and indeed, depressed – at how people when standing before a painting in a gallery will choose to view it through the screen of their camera, rather than look directly). This difference between experiencing a painting and seeing it in a book is itself an interesting area to research, and one I’ll be looking at over the coming months. Nevertheless, reproductions can still tell us a great deal, so with this in mind I shall begin with the painting shown above.

I have always been drawn to a certain kind of aesthetic, one which you’ll often find in places of decay, where time has taken hold of a building and chewed upon it like a dog with a bone. The aesthetic of time or the passage of time is beautiful in its relentlessness; from crumbling walls and cracked plaster, to buckled paint layers and the weary look of old books and photographs. It’s something which, for whatever reason, captivates me, whether I’m there amongst the glorious ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum; walking down a hot and dusty street in Siracusa; looking at a long abandoned tomb in Montparnasse or standing in my old school, just before its scheduled demolition. Indeed, it was in my old school that I photographed the window sills, scratched with the names of bored pupils from the 1970s, and it wasn’t so much the names that interested me, rather, the look of those names; an aesthetic which we find in Cy Twombly’s Panorama, painted in 1955.

I can anticipate what many might say when confronted with a painting such as this. ‘I could do that’ is a usual retort, or even worse, ‘a child could do better.’ Which is of course not the point. Whenever someone says ‘I could do that,’ I always point out that they haven’t, and that, in all likelihood, they’d have no reason to try. ‘I could’ in this instance, is just another way of saying ‘I haven’t’. And while I’m not going to extol its virtues as a great work of art, a work of art this painting is and one which, for whatever reason I’m particularly drawn to.

But why? What is it about this piece that I find so engaging?

Without wishing to sound too shallow, first and foremost it’s the look of the painting which appeals. Looks matter for me in art, but that’s not to say art should be beautiful (nothing could be further from the truth); but it needs to be engaging. In order to hold the attention of the viewer, in order to attract them in the first place, you need to trigger something within them. To use a rather crude analogy, it’s rather like the cover of a book and the subsequent opening line. Get it right and your story with its deep themes and intricate plots may well get the chance to be revealed. Get it wrong and no matter how perfect the rest of the book, the potential reader will never get to know. As I’ve said, this is a crude analogy, and I don’t wish to dwell on the idea of a painting being analogous to a book; but nonetheless artists have something to say and how they say it matters. Of course there are no rules governing taste, and what one person likes another will dislike, or even hate.

In the case of Panorama, it’s a painting I’ve come to love.

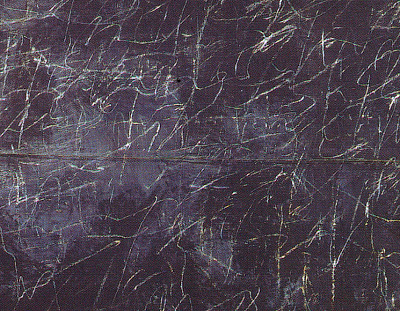

Looking at this painting (a detail is shown above) is like looking at a wall upon which people have scratched words and names, which then over time have lost their shape and meaning. The scratches are words or signifiers reduced to a new kind of text yet to be deciphered. Not that as a viewer I’m trying to make sense of all the lines or even groups of lines. This isn’t a game of ‘pick-up-sticks,’ where individual elements are teased out from the apparent chaos.

Something which in a moment was possessed with meaning, means nothing now, and all those moments, layered one on top of the other, create as a result, a palimpsest of ambiguous symbols signifying a strange kind of nothingness; a presence which at the same time is also an absence. People come and people go, and in some respects, this painting is for me a work about time – about the simultaneity of what I’ve just described: presence and absence.

Of course we know that this is the work of one man, but even so, there is a sense of a multitude of meanings. If it’s not a collection of thoughts, then it’s a mass of independent actions; a multitude of presents, wrapped up in a simultaneous slab of the past.

The shades of grey, smudges and rapid scrawls, also call to mind a blackboard, on which someone has poured out their thoughts in the hope of distilling them down into an equation – a simple truth. I’ve always loved the aesthetic of the blackboard (as well as mathematics); the half revealed texts and mathematical symbols, the swirling smudges of rubbings out, the dust and the physicality of thought. (I’m only glad we didn’t have whiteboards or even worse, smartboards when I was at school). This could be a painting about obfuscation, of concealment, where something has been scratched out and hidden from view. Or perhaps it’s the opposite, a painting that is looking, searching for that something which remains elusive?

We can follow lines, from one to the next in our own search, but we’re always held on the surface; we cannot penetrate the painting’s depth. And depth there must be, for the work could not have been made in an instant, but gradually over the course of time. It is then a panorama, viewed in a moment, and made of many thousands.