Drawings made with old charcoal excavated from a test-pit, during an archaeological dig in Iffley, Oxford.

John Malchair 1770

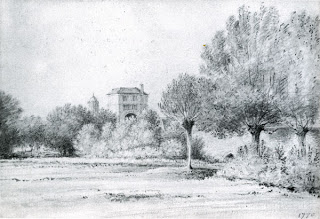

The following is a drawing made by John Malchair showing the causeway of what is now Abingdon Road. The rather unusual building is Friar Bacon’s Study which was demolished in 1779. Beneath the drawing is a photograph showing the same causeway, with two arches, a little bit like the arch which can be seen in the drawing.

Abingdon Road

One of my favourite drawings is that made by a German-born, Oxford-based artist called John Malchair, who lived and worked in the city in the late 18th century. The drawing shows a view of the Abingdon Road as it appeared in 1770 with the strange and imposing edifice of Roger Bacon’s study in the foreground – a building that was demolished nine years later – and the familiar, extant structure of Christ Church College’s Tom Tower behind.

There’s something beguiling about the image, depicting as it does the city long before the car, before its expansion into the suburbs when still surrounded by fields and meadows. It’s a quiet almost pastoral scene in which I feel I can hear the birds and feel the sun on my face. I can almost hear the quietude, contrasting it with the sounds I would hear today if I stood in a similar position; indeed, it’s an image in which I am constantly contrasting, moving back, to and fro between the past and the present.

This contrast between the past and present is what I experience as I research my family tree and this image I’ve lately realised embodies some of my recent thinking and research. My great-great-great-great-grandfather, Samuel Stevens, born in 1776, lived and worked as a tailor on St. Aldates in Oxford, a street which is in effect a continuation of Abingdon Road as it moves towards and connects with Carfax in the city centre. I like the fact that he is contemporary with this image and would have been alive (if only a small boy) when Roger Bacon’s study was still standing.

On the other side of my family tree, on my father’s side, my great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, William Hedges lived and worked in Abingdon, a town in which his line lived until George Hedges moved to Oxford sometime around 1869 when he married Amelia Noon, daughter of Charlotte Noon, murdered by her husband Elijah in 1852 (see ‘A Murder in Jericho‘). It’s very likely of course that both these lines (the Stevens’ and the Hedges’) continued back in those same places (Oxford and Abingdon) for further generations, and I like the fact that in this image by Malchair, and in a sense in the building he drew, is a connection between the two. Not only that, there is a connection between my past and my present, as if that connection might be found in the road between Oxford and Abingdon.

Finally, in a project I started some time ago (6 Yards 0 Feet 6 Inches) I make mention of a survey by John Gwynn, carried out in 1771 in which all the residents of Oxford are listed along with the measurements of their properties. It’s a fascinating document in its own right, but if Samuel Stevens’ parents lived in Oxford just a few years before his birth, they would be listed in that survey. Flicking through there are a number of Stevens’ and I can’t help but think one of them is my ancestor.

Memory – The Poor Draughtsman

I have for a long time been interested in memory and how – in terms of its visual fidelity to the thing remembered – it is a rather poor draughtsman. I was thinking of this in terms of how I ‘see’ Oxford when I am remembering it – a street, a building and so on. The city is of course a place I have known well for many, many years and yet, if I try and draw a building (for example Magdalen Tower) or a street (such as the High), I realise very quickly, as I explore the image in my mind (and on the page) that what my mind takes as being Magdalen Tower and High Street has more in common with a ruin that the real thing. That is not to say I see a smouldering pile of blackened stones and charred twisted timbers, but rather, the image which comprises – in my mind at least – the whole, is in fact made up of miscellaneous fragments which are often unrecognisable or entirely out of sequence.

As with the work I did on Auschwitz, I decided to try and draw Oxford, and the following were made with my eyes closed.

In light of my Tour Stories: Oxford Destroyed project, I found these images particularly resonant, and I began to wonder what would happen if I did the same with text; free-writing about a building as I see it in my mind.

Dreamcatcher X

Today I began to install the Dreamcatcher work at MAO which after a while trying to package up the ‘net’ I finally managed to do. Right away I was taken aback by the difference between the work as it appeared in my studio and the work as it appears in the gallery; there is something rather staid about it which might be to do with the lighting (which we will work on tomorrow) and the power-socket in the corner. It just seems at present to be a decorative hanging.

The other problem for me is the backdrop which still looks a bit contrived; the sheets of music are I think essential but the way they are presented isn’t quite working. It might be down to the fact there isn’t enough paper so I bought some more today and will add that tomorrow morning.

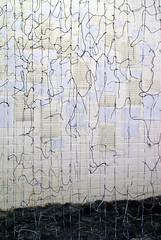

The detail below shows for me the importance of the manuscript paper as one sees the net superimposed upon it as if it is music written on the page. I guess it’s just a case of trial and error at the moment, but in the case of this show I might removed the paper altogether.

Another option might be to go back to the original idea and add the drawn images of Auschwitz?

Dreamcatcher IX

Thinking about the backdrop for the Dreamcatcher I have decided that it would be best to stick with just empty sheets of manuscript paper rather than bits of everything else. The trouble is I haven’t collected enough different types of paper and having just three things (manuscript paper, postcards and lined paper) makes it as a whole look a bit ‘cobbled together’ and rather contrived. Having just the manuscript paper however helps me to avoid this. Furthermore it makes for a stronger piece. With just the empty manuscript paper as a backdrop, the cut string would become just the unwritten notes, unsung music; and they would I believe be more pertinent to the theme of lost voices, silenced voices. There is something more human about these pieces of string being unplayed or unsung music.

One particularly interesting contrast is the idea of music (sung music in particular) filling a space. One can imagine the sound waves with the potential of filling a vast area and then the pile of unsung notes (unheard voices) piled in just a corner. There is the difference too in the quality of the two; the sound being light and the string being dense and heavy.

I am reminded here of something I read in Bill Viola’s collection of writing: ‘Reasons for Knocking at an Empty House. Writings 1973-1994’.

“Chartres and other edifices like it have been described as ‘music frozen in stone’. References to sound and acoustics here are twofold. Not only are there the actual sonic characteristics of the cavernous interior, but the form and structure of the building itself reflects the principles of sacred harmony – a sort of ‘acoustics within acoustics’. When one enters a Gothic sanctuary, it is immediately noticeable that sound commands the space. This is not just a simple echo effect at work, but rather all sounds, no matter how near, far or loud appear to be originating at the same place. They seem to be detracted from the immediate scene, floating somewhere where the point of view has become the entire space.”

I’m particularly interested in the idea of the net being a score of sorts, one that can be sung or played (I like the idea of the cello being used in this context, as this instrument, a mournful one in many ways, has often been described as being the closest sounding instrument (in terms of its timbre) to the human voice. If one was using the net as a score, what would one be playing? The lines of the string, the intersections (knots) or the spaces between?

In many ways, this takes me back to a research project I started, but on which I never worked that much called Pathways Project. And already a title has come to mind. Dead Light: Unsung.

Dreamcatcher VIII

This afternoon I worked on a possible ‘backdrop’ for the Dreamcatcher installation which will itself be installed at MAO on wednesday. As it stands (without the backdrop), it works, but I want to make a connection between the string and text, music, drawing etc. and the idea of the pile of string being a pile of unwritten words, unwritten music and so on. One idea I’ve had is to place pieces of blank paper, postcards, manuscript paper and writing paper on the back wall, and all the while I’ve thought about it, the more the image of the ‘rescued’ Jewish gravestones made into a memorial war in Kazimierz-Dolny (Poland) appeared in my mind.

So with my various pieces of paper, I went to the studio and made an attempt at creating something. The results are as below:

Looking at the above, one can see a connection with the image below – the wall in Kazimierz-Dolny.

Below, is the backdrop as seen behind the net and the string.

So, I think this idea works very well, my only problem is the quality of the fragments. As the above was made this afternoon, just to see how it would look, I’m a little unsure of how it should be displayed come Thursday when it’s installed in MAO. I think the paper is important but I’m not sure blu-tacking is good enough. Also the paper looks too clean and the postcards I think should go (maybe just one or two pieces). The main thing is not to let it look too contrived; the string and the net work well, at the moment the paper fragments jar just a little – something to work on tomorrow and Monday.

Oxford Destroyed – Images

I was thinking the other day about the images our memories present to us and what they represent in the real world. I have been interested for a long time in what exactly remembered images are, and having thought about my Tour Stories Project (Oxford Destroyed) I started to think about Oxford as it exists in my memory. If I picture the High Street what do I see, and, if I try and draw that image, what does it look like? I supposed the resulting image would not be unlike a ruin and so I tried it out.

In many ways, the images I drew of what I could see in my memory were like images of the city in ruins, and in many respects, the remembered city is a ruin – it has, after all, in terms of its temporality, passed by.

In Sebald’s novel Austerlitz, Austerlitz states that fortifications:

“…cast the shadow of their own destruction before them, and are designed from the first with an eye to their later existence as ruins.”

I think in some respects this might apply to any structure and their later existence as memories.

Dreamcatcher VII

On my way to Luxembourg, I considered the pile of string and went over what I’d previously written, that the lines equate to hair, memories of the individual, individuals themselves, written words, unspoken words. The dreamcatcher, I summarised, is the attempt of the tourist to piece together a moment from the mass of dead light. It is the attempt to imagine what victims might have written /thought at the time (unwritten words) and maybe in the future; it is the attempt to piece together unsung melodies (music) and, to some extent, unsaid words (wires). But how do I help people make that connection?

Could I use postcards, manuscript paper, writing paper?

Having drawn the above (right-hand side) I was reminded of the wall of broken/displaced gravestones myself and Monika saw in Kazimierz-Dolny.

If I use postcards, manuscript paper, writing paper and so on (put on the wall behind the pile of string) would it be best to rip them and attempt to put them back together in the manner of the wall?

Dreamcatcher VI

I spent a couple of hours in the studio this afternoon cutting up the string which will go on the floor beneath the net of the dreamcatcher. Quite a bit of the string (which was dyed in balls) had remained relatively untocuhed by the dye, yet all the same, this gave the pile of string an interesting appearance. Of course there is no getting away from the fact that the pile alludes to the mountain of human hair which one can see in the museum at Auschwitz, but as I cut more of the string, I saw the string not so much as hair as unwritten words. The fact that some of it was white, ‘uninked’ as it were made me think of words that had been written and then erased. The way the dye has taken to some of the string has also given it the appearance of wire, and again this added to the idea of things left unwritten, but in this instance, things left unsaid, as if the wires were phone wires.

If this pile of string is to allude to things never said and never-written then the dreamcatcher becomes an attempt by the tourist (the viewer) to imagine what they (the victims) might have said and might have written. But like the dreamcatcher as something of an appropriated cultural symbol, the net of words and ‘voices’ are also appropriated from a decimated culture and can in no way tell us what it was really like to be there. Dreamcatchers let the good dreams through and ensnare the nightmares; we can never know what it was like to be there, and we will always pass through.

The question is, how do I enable the viewer to understand the string as unwritten words?

Wallpaper

Today I started wallpapering the drawings I described in the previous entry to a wall in my studio in order to see how they would look and to see what techniques would be best for the installation at MAO. After a while, it became clear that the effect wasn’t quite what I was hoping for. I must admit I’d expected as much given that the drawings are all very similar – practically identical – being as they are, drawn on white A4 sheets of copy paper.

What I need to to is to create many more drawings (still including those on A4 sheets), drawn on different types/qualities of paper and of various sizes. I need to give the impression that this is the work of an obsessive mind to some degree, and therefore, the idea of scribbling drawings on whatever comes to hand would best be served by this change in approach.

Another thing to consider is the installation of the work itself. How might I create readymade wallpapered walls?

As it stands, there are things about the way the work looks that interest me. One things is the way it calls to mind the wallpaper one might find in a child’s bedroom; repeated motifs – the stuff of nightmares after dark, which, incidentally, ties in with a related project based around the story of Hansel and Gretel.

Talking of wallpaper has brought to mind an extract in Eric L. Santer’s book, ‘Of Creaturely Life, taken from Rainer Maria Rilke’s novel, ‘The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge.’

“It was, so to speak, not the first wall of the existing house (as you would have supposed), but the last of the ones that were no longer there. You could see its inside. You could see, at its various stories, bedroom walls with wallpaper still sticking to them; and here and there a piece of floor or ceiling. Near these bedroom walls there remained, along the entire length of the outer wall, a dirty white space through which, in unspeakably nauseating, worm-soft digestive movements, the open, rust-spotted channel of the toilet pipe crawled. The gaslight jets had left dusty grey traces at the edges of the ceiling; they bent here and there, abruptly, ran along the walls, and plunged into the black, gaping holes that had been torn there. But the most unforgettable things were the walls themselves. The stubborn life of these rooms had not let itself be trampled out. It was still there; it clung to the nails that were left, stood on the narrow remnant of flooring, crouched under the corner beams where a bit of interior still remained. You could see it in the paint which it had changed, slowly, from year to year: blue into mouldy green, green into grey, yellow into a faded, rotting white. But it was also in the places that had been kept fresher behind mirrors, paintings, and wardrobes; for it had traced their outlines over and over, and had been with cobwebs and dust even in these hidden places, which were now laid bare. It was in every flayed strip of surface; it was in the dame blisters on the lower edges of the wallpaper; it fluttered in the torn-off shreds, and oozed from the foul stains which had appeared long before. And from these walls, once blue, green, and yellow, and now framed by the broken tracks of the demolished partitions, the air of these lives issued, the stubborn, sluggish, musty air which no wind had yet scattered. There the noons lingered, and the illnesses, and the exhalations, and the smoke of many years, and the sweat that trickles down from armpits and makes clothing heavy, and the stale breath of mouths, and the oily smell of sweltering feet. There the pungent odour of urine lingered, and the odour of soot, the grey odour of potatoes, and the heavy, sickening stench of rancid grease. The sweet smell of neglected infants lingered there, the smell of frightened schoolchildren, and the stuffiness from the beds of pubescent boys. And all the vapours that had risen from the street below, or fallen down from above with the filthy urban rain.”

Weeping

The following drawing is part of a series I’ve been working on regarding Auschwitz-Birkenau and the theme of pathways.

Looking at the picture, I was reminded of something which for a while escaped me. There was something about the tower in particular which I was sure bore a striking resemblance with another, famous painting.

The following is a detail from the drawing.

Looking at it closely, at the apparent anguish and suffering in the ‘face’ of the tower (the tower as suffering goes against all I have written about it so far: “…the gate house is different, it knows its time has passed but doesn’t seem ashamed in anyway. Its almost as if it relives every moment in its glass eyes, glass eyes which are far from being blind. They don’t reflect what they see around them now but rather what has been, what the tower wants to remember…”) made me think at once of the painting I’d been thinking of, an image painted in 1937 and again, one of the utmost despair: Picasso’s ‘Weeping Woman’.