The following image is taken from Tom Phillips’ book, Postcard Century. I was reminded on looking at the image of a piece I made called Dreamcatcher and in particular a photograph I took of work in progress.

Music and Text

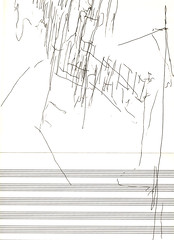

As part of a new project, I’ve been looking at ways of creating musical scores. As someone who composes music but cannot read it, I find this particularly interesting inasmuch as I’m looking to write a piece of music but want to do so, not by ‘feeling’ the music as I’m playing it (as is how I normally do it), but rather, through a process of ‘writing’ it down first. The scoring should, furthermore, be linked with the theme of the piece. For example, for the music I want to write as part of my Tour Stories: Oxford Destroyed project, I’ve tried drawing remembered images of the city, blind on a piece of manuscript paper.

It was whilst making work for a project “The Ordinary Language of Freedom” that I became aware of how what I was doing (writing on a window) reminded me of the look of music – a link made manifest perhaps by dint of the fact I cannot read it.

And prior to this, music – and in particular, musical scores – surfaced towards the end of my work on the Dreamcatcher project, where I began to see the piles of string as unsung/unwritten notes and the net as an attempt to piece them together – to write, in effect, a score of unwritten music.

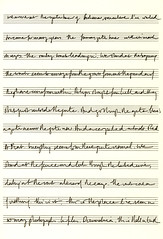

I began by considering what what one can derive from a blank sheet of manuscript paper. Comparing it with an ordinary blank sheet of paper there is clearly a difference. The staves somehow resonate, they make a sound even when there is nothing on them, and remind me of the silence one encounters in churches; pregnant with echoes (one thinks here again of Bill Viola’s discussion of sound in Chartres catherdral). When the text is written upon the staves (as above), the text becomes music, but of a different kind. The words are not words to be sung (that would be the case if the words were written beneath the staves and notes upon them) neither are they to be spoken. If the words are written beneath the staves without notation then they become neither words to be sung or spoken. They are not music. They are not simply text. They become lost.

Looking at some past text work I made as part of my OVADA residency (‘Wound’), I thought of repeating the work using manuscript paper.

The results were particularly interesting.

There is something about this piece which I find particularly resonant. The text is taken from a piece of writing I made following my visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau in which I describe the silence of the place; one, which like that in churches, I remember as being pregnant with the past. Looking at it closely, I was in fact reminded of mediaeval manucripts.

I need to explore these ideas more throughly, which in part I will do through a new project (6 Yards 0 Feet 6 Inches) and then, with a few ‘scores’ in hand, I will start to create some music based upon them.

Dreamcatcher X

Today I began to install the Dreamcatcher work at MAO which after a while trying to package up the ‘net’ I finally managed to do. Right away I was taken aback by the difference between the work as it appeared in my studio and the work as it appears in the gallery; there is something rather staid about it which might be to do with the lighting (which we will work on tomorrow) and the power-socket in the corner. It just seems at present to be a decorative hanging.

The other problem for me is the backdrop which still looks a bit contrived; the sheets of music are I think essential but the way they are presented isn’t quite working. It might be down to the fact there isn’t enough paper so I bought some more today and will add that tomorrow morning.

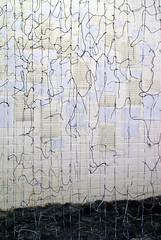

The detail below shows for me the importance of the manuscript paper as one sees the net superimposed upon it as if it is music written on the page. I guess it’s just a case of trial and error at the moment, but in the case of this show I might removed the paper altogether.

Another option might be to go back to the original idea and add the drawn images of Auschwitz?

Dreamcatcher IX

Thinking about the backdrop for the Dreamcatcher I have decided that it would be best to stick with just empty sheets of manuscript paper rather than bits of everything else. The trouble is I haven’t collected enough different types of paper and having just three things (manuscript paper, postcards and lined paper) makes it as a whole look a bit ‘cobbled together’ and rather contrived. Having just the manuscript paper however helps me to avoid this. Furthermore it makes for a stronger piece. With just the empty manuscript paper as a backdrop, the cut string would become just the unwritten notes, unsung music; and they would I believe be more pertinent to the theme of lost voices, silenced voices. There is something more human about these pieces of string being unplayed or unsung music.

One particularly interesting contrast is the idea of music (sung music in particular) filling a space. One can imagine the sound waves with the potential of filling a vast area and then the pile of unsung notes (unheard voices) piled in just a corner. There is the difference too in the quality of the two; the sound being light and the string being dense and heavy.

I am reminded here of something I read in Bill Viola’s collection of writing: ‘Reasons for Knocking at an Empty House. Writings 1973-1994’.

“Chartres and other edifices like it have been described as ‘music frozen in stone’. References to sound and acoustics here are twofold. Not only are there the actual sonic characteristics of the cavernous interior, but the form and structure of the building itself reflects the principles of sacred harmony – a sort of ‘acoustics within acoustics’. When one enters a Gothic sanctuary, it is immediately noticeable that sound commands the space. This is not just a simple echo effect at work, but rather all sounds, no matter how near, far or loud appear to be originating at the same place. They seem to be detracted from the immediate scene, floating somewhere where the point of view has become the entire space.”

I’m particularly interested in the idea of the net being a score of sorts, one that can be sung or played (I like the idea of the cello being used in this context, as this instrument, a mournful one in many ways, has often been described as being the closest sounding instrument (in terms of its timbre) to the human voice. If one was using the net as a score, what would one be playing? The lines of the string, the intersections (knots) or the spaces between?

In many ways, this takes me back to a research project I started, but on which I never worked that much called Pathways Project. And already a title has come to mind. Dead Light: Unsung.

Dreamcatcher VIII

This afternoon I worked on a possible ‘backdrop’ for the Dreamcatcher installation which will itself be installed at MAO on wednesday. As it stands (without the backdrop), it works, but I want to make a connection between the string and text, music, drawing etc. and the idea of the pile of string being a pile of unwritten words, unwritten music and so on. One idea I’ve had is to place pieces of blank paper, postcards, manuscript paper and writing paper on the back wall, and all the while I’ve thought about it, the more the image of the ‘rescued’ Jewish gravestones made into a memorial war in Kazimierz-Dolny (Poland) appeared in my mind.

So with my various pieces of paper, I went to the studio and made an attempt at creating something. The results are as below:

Looking at the above, one can see a connection with the image below – the wall in Kazimierz-Dolny.

Below, is the backdrop as seen behind the net and the string.

So, I think this idea works very well, my only problem is the quality of the fragments. As the above was made this afternoon, just to see how it would look, I’m a little unsure of how it should be displayed come Thursday when it’s installed in MAO. I think the paper is important but I’m not sure blu-tacking is good enough. Also the paper looks too clean and the postcards I think should go (maybe just one or two pieces). The main thing is not to let it look too contrived; the string and the net work well, at the moment the paper fragments jar just a little – something to work on tomorrow and Monday.

Dreamcatcher VII

On my way to Luxembourg, I considered the pile of string and went over what I’d previously written, that the lines equate to hair, memories of the individual, individuals themselves, written words, unspoken words. The dreamcatcher, I summarised, is the attempt of the tourist to piece together a moment from the mass of dead light. It is the attempt to imagine what victims might have written /thought at the time (unwritten words) and maybe in the future; it is the attempt to piece together unsung melodies (music) and, to some extent, unsaid words (wires). But how do I help people make that connection?

Could I use postcards, manuscript paper, writing paper?

Having drawn the above (right-hand side) I was reminded of the wall of broken/displaced gravestones myself and Monika saw in Kazimierz-Dolny.

If I use postcards, manuscript paper, writing paper and so on (put on the wall behind the pile of string) would it be best to rip them and attempt to put them back together in the manner of the wall?

Dreamcatcher VI

I spent a couple of hours in the studio this afternoon cutting up the string which will go on the floor beneath the net of the dreamcatcher. Quite a bit of the string (which was dyed in balls) had remained relatively untocuhed by the dye, yet all the same, this gave the pile of string an interesting appearance. Of course there is no getting away from the fact that the pile alludes to the mountain of human hair which one can see in the museum at Auschwitz, but as I cut more of the string, I saw the string not so much as hair as unwritten words. The fact that some of it was white, ‘uninked’ as it were made me think of words that had been written and then erased. The way the dye has taken to some of the string has also given it the appearance of wire, and again this added to the idea of things left unwritten, but in this instance, things left unsaid, as if the wires were phone wires.

If this pile of string is to allude to things never said and never-written then the dreamcatcher becomes an attempt by the tourist (the viewer) to imagine what they (the victims) might have said and might have written. But like the dreamcatcher as something of an appropriated cultural symbol, the net of words and ‘voices’ are also appropriated from a decimated culture and can in no way tell us what it was really like to be there. Dreamcatchers let the good dreams through and ensnare the nightmares; we can never know what it was like to be there, and we will always pass through.

The question is, how do I enable the viewer to understand the string as unwritten words?

Dreamcatcher V

Due to the fact that my original idea for the MAO exhibition has had to be changed (instead of a whole room for the work I have now been allocated a corner) I have had to rethink the idea in relation to this new and smaller space. Clearly the original idea – which was to have given the impression of someone obsessed, with all four walls wallpapered with drawings – won’t work in just a corner. Far from being an installation, the work would become little more than a collection of drawings on the wall. Therefore I have had to rethink the piece which I’ve done by concentrating on the Dreamcatcher part of it, focussing on what a Dreamcatcher is in modern, contemporary culture. Of course changing the piece means changing the catalogue entry:

“While originating with Native American Indians, the Dreamcatcher today is more likely thought of as a negative symbol of cultural appropriation – little more than a trinket for the tourist derived from a decimated culture. Traditionally, they were said to let good dreams through whilst ensnaring nightmares and have become a part of my work through consideration of my role as a so-called ‘Dark Tourist,’ visiting – through my studies – sites such as Auschwitz. Death is described by the pieces of string – the thread of life drawn, measured and cut; each one tied to make the Dreamcatcher. We, like the good dreams can always pass through.”

I am currently negotiating the possibility of a show at a conference on ‘Dark Tourism’ in April this year and so this new angle on the work has intrigued me. It remains to be seen whether this will be accepted by the curators of the Brookes MAO show, but if not, it’s certainly something I can continue to explore and show elsewhere.

Dreamcatcher IV

In my latest session of work on the Dreamcatcher installation, I have started to add to those drawings already wallpapered to the wall. The drawings as they stand work well, but with the string aspect of the installation they need to become more like a single mass of lines rather than a collection of individual works. Therefore, I have started to draw directly on the walls, drawing large and small versions of the image. This for me leant itself neatly to the notion of an obsessive mind working on the question of how such a thing could have happened. Also, the constant drawing on a large scale (scale in terms of the physical space of the images rather than a single image itself) called to mind a mathematician working out a puzzle – trying to find an answer. There was also the action of the drawing itself; for the first time I found myself drawing with my eyes open, and yet, despite this the image of the gatetower produced was identical with that made when my eyes were closed; it seems there is no answer to be had, just an endless puzzle to be worked on.

There is also the sense as I am drawing of becoming trapped by the lines, of becoming imprisoned or ensnared by them; the more lines I make the less the chance of escape – the less chance of an answer.

The net of course which will hang in the centre of the piece is the ‘dreamcatcher’, something which lets the good dreams through and ensnares the nightmares and therefore there is this correlation between the two aspects of the piece.

I can easily imagine a piece of work in which this idea is explored – a performance piece in which standing before a large blackboard I make a series of chalk drawings as if I am trying to find an answer.

This I will explore in the coming weeks.

As things stand now, I need to start working on the string element of the piece. I have already worked on a ‘net-like’ piece using pieces of cut string (denoting both the lives of many individuals and an individual’s memories) and took a few pictures of the drawing through this net, just to start giving me a sense of the overall work.

Having discussed the idea above, I couldn’t help but invert one of the photographs to see how a blackboard version might appear. The outcome reminded me of an animation I made from the first drawings I ever did in this series which can be found by clicking here.

Dreamcatcher III

Having completed one side and a corner of the installation ‘prototype’, pasting approximately 300 A4 drawings onto my studio walls, I believe that my initial concerns about the sizes of the individual drawings may be unfounded. In fact, as the walls have dried, and more images have been pasted on top of one another, the overall effect is as I’d first envisaged it.

Working in a corner has been important in this respect, as I can get a better impression of how the whole room will come together. The next stage will be adding in the string.

Forgetting

Today I started work on my Dreamcatcher installation which will be installed in Modern Art Oxford in March 2008 as part of the Brookes Exhibition which runs for approximately nine days. Part of the installation comprises hundreds of drawings which I will wallpaper on the walls of a room, and in preparation for a trial version of the piece I created about 100 drawings this morning. And it was whilst making these drawings that I became aware of how, after a while, my hand seemed to be working quite independently of my mind. The lines of the drawing had come to form a pattern of sorts and my hand was simply going through the motions, churning out images not of the gate tower of Auschwitz-Birkenau per se, but rather drawings of drawings of the gate-tower of Auschwitz-Birkenau. My memory had become a pattern and although this did at first disconcert me, in the end I came to see it as something positive, insofar as my work on memory and memorials is concerned.

In his book ‘Present Pasts – Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory,’ Andreas Huyssen asks:

“Is it the fear of forgetting that triggers the desire to remember, or is it perhaps the other way around? Could it be that the surfeit of memory in this media-saturated culture creates such overload that the memory system itself is in constant danger of imploding, thus triggering fear of forgetting?”

I would take this further and suggest that the overload of the memory system does not necessarily trigger a fear of forgetting, but rather it triggers forgetting itself. I was also reminded of Frances A. Yates’ book ‘The Art of Memory’ in which she discusses Socrates’ story of the invention of writing by the God Theuth.

“In the Phaedrus; Socrates tells the story of the God Theuth who invented numbers and arithmetic, geometry and astronomy, draughts and dice, and most importantly of all, letters. The king of all Egypt was the God Thamus who told Theuth that the invention of writing was not, as suggested, an elixir of memory and wisdom, but of reminding; the invention will produce forgetfulness.”

If one equates my line drawings with text, one can see how the re-remembering of the memory of Auschwitz-Birkenau through drawing has resulted (at least whilst making the drawings) in that memory being forgotten. What I’m actually remembering is not my visit, but a memory of that visit. And as such these drawings are somehow equivalent to post-memories; memories we might have of the Holocaust which of course we never experienced.

So what does this mean for the Dreamcatcher work?

The work itself is in part about how we can visit places such as Auschwitz-Birkenau, safe in the knowledge that we can leave; just as we know we’ll always wake from our nightmares. Dreams and nightmares will eventually fade – they will be forgotten; they are unreal, much like our own post-memories of unwitnessed events.

So what is brought into question therefore is how best to remember atrocities such as Auschiwtz, the Holocaust and War in general?

Dreamcatcher II

Whilst working on my ‘Dreamcatcher’ project/installation today, I thought again about the idea of it being a piece of music, and, as I thought, a visitor to the studio (Tiffany, who has a very nice voice) decided to try and ‘sing it’, along with Philippa (who first suggested it looked like music). Using the vertical strings as measures and the horizontal strings as indicators of notes on a scale, they sang the entire work, and, although it was a bit of fun, the sound they made did remind me of a kind of lamentation. As I worked on the strings, untangling them and tying knots etc. I felt as if I was playing some kind of instrument – something like a harp.

I also thought a lot about the action of weaving, for it’s felt these past two days as if I’ve been creating a piece of clothing, and, given what these cut strings or threads represent, I was reminded of a quote from Roland Barthes’ ‘Camera Lucida’.

“Clothes make a second grave for the loved being.”

A second grave is somehow analogous with the idea of post-memory, for if one sees the clothes of someone who has passed away, one can somehow imagine them without really knowing who they were, just as post-memory allows one to get a feel for a past event without having witnessed the actual moment itself.

Dreamcatcher

In March 2008, Brookes will be showing a select number of works at MAO (Modern Art Oxford) and so I have decided to submit two proposals, one of which is entitled ‘Dreamcatcher’. The following extracts are taken from that proposal, the first section being ‘about me’ and the second ‘about the work’.

“As an artist, my main areas of interest are time, memory and remembering, with a particular emphasis on postmemory and its formation within the individual consciousness. Examining past events such as World War 1 and the Holocaust, my work seeks to explore how we formulate memories of times when we were not born, or of events to which we were not witness. What strategies do we employ in reconstructing the past? Contemporaneous objects, documents, photographs, verbal and written testimonies/narratives can all be used by the imagination to create postmemories, but what role do they play in the present-day, real-time, world?”

“An installation comprising a single room, all four walls of which are wallpapered with hundreds of drawings (see attached images for completed examples). These are drawings of the gate-tower at Auschwitz-Birkenau as remembered by myself following my visit there in October 2006. In the centre of the room, a net is suspended from the ceiling, created from hundreds of pieces of black string knotted together; a physical version of all the drawings, as if they were shown on a single piece of paper, and as if the ink had been turned into string.

The drawings themselves could be said to represent a last, snatched glance at the gate-tower of Birkenau and their number a testament to the number of people who died there. It could also be said to reveal my own incomprehension of standing in a place where over a million people died (a conflict between memory and postmemory), each death a piece of string – the thread of life drawn, measured and cut, as according to Greek Mythology – and tied to make the Dreamcatcher. Dreamcatchers are said to let good dreams through and ensnare nightmares, and for all the victims, Auschwitz-Birkenau was exactly that – a catastrophic nightmare.”

Today I started to create a prototype net at my studio and like all these things, it proved quite different in the way it began to develop off the page. Firstly, I tied a piece of string across my space about 7 feet off the ground and then attached vertical pieces which extended down to the floor. Almost straight away, I found myself thinking of a gallows.

When it came to tying the horizontal strings, I used the pile of cut strings which proved rather difficult to use, but I used them nevertheless, and the action of tying, again proved interesting albeit for very different reasons than before. Each knot felt just like an act of remembrance. It was a positive act rather than a negative one.

Having completed a number of the horizontal strings, a colleague in the studio told me that she thought it looked like a musical score of some kind. I was thinking that it looked like writing; but this idea of it being musical was interesting.