I remember as a small boy how my Nana would on occasion take me and my older brother to where she worked as a Housekeeper. The house was – at far as I recall – a big, white, Modernist building with a large well-kept lawn at the rear. But what I remember most was the wood which stood at the edge of the garden. I can see it now – that contrast between the manicured lawn and the wild dark of the trees, and with the work that I’ve been doing on gardens, trees and contrasts, this particular memory has suddenly sprung to life.

One day in 1845

The fact that we exist, as the individuals we are, is mind-boggling. Go back 8 generations and you’ll discover that you have 256 great-great-great-great-great-great-grandparents. Go back to the start of the 1600s and you’ll discover that you owe your existence to 1,024 people who were alive at the time; 2,046 including those who came after.

No-one of course lives their lives in isolation. We spend every day interacting with friends, family or strangers, and as such, all those people too have influenced our coming-into-being.

My 9th great-grandfather, Gabriel Baines (born in 1610) was one of 1,024 people alive around the time on whom my existence has depended. Factor into that equation, that everything (and I mean everything) those 1,024 people did in the early 1600s had to be done exactly as it was, then you begin to appreciate how extremely unlikely you are. (Extrapolate this out and one could say that everything that everyone did had to be done as it was for any of us to be born who were are.)

Leaping ahead from the early seventeenth century to the mid 19th century I find my great-great-great-grandparents. Since beginning my research in 2007 I have discovered all 32 of them. Imagine then a day in 1845. All 32 of these individuals were living in England and Wales (their ages and place of residence at the time shown in brackets).

Richard Hedges (37 – Dorchester, Oxfordshire)

Ann Hedges née Jordan (38 – Dorchester, Oxfordshire)

Elijah Noon (27 – Oxford, Oxfordshire)

Charlotte Noon née White (26 – Oxford, Oxfordshire)

William Lafford (21 – Ampney St Peter, Gloucestershire)

Elizabeth Timbrill (18 – Minety, Gloucestershire)

Abel Wilson (27 – Ampney Crucis, Gloucestershire)

Hester Wilson née Pillinger (22- Ampney Crucis, Gloucestershire)

Alexander Jones (44 – Mynyddyslwyn, Monmouthshire)

Martha Jones née Harries (27 – Mynyddyslwyn, Monmouthshire)

Edmund Jones (28 – Trevethin, Monmouthshire)

Sarah Jones née Jones (27 – Trevethin, Monmouthshire)

Enos Rogers (4 – Clutton, Somerset)

Jane Tovey (4 – Llanfoist, Monmouthshire)

Alfred Brooks (7 – Bettws, Monmouthshire)

Ruth Waters (5 – Machen, Monmouthshire)

John Stevens (33 – Reading, Berkshire)

Elizabeth Stevens (28 – Reading, Berkshire)

Charles Shackleford (28 – Reading, Berkshire)

Mary Ann Jones (20 – Reading, Berkshire)

John Thompson (31 – West Walton, Norfolk)

Maria Thompson née Hubbard (33 – West Walton, Norfolk)

William Baines (20 – Gainsborough, Lincolnshire,)

Martha Baines née Moore (20 – Gainsborough, Lincolnshire,)

George Sarjeant (31 – Lewes, Sussex)

Sarah Sarjeant (39 – Lewes, Sussex)

James Barnes (23 – Arlington, Sussex)

Eliza Barnes née Deadman (21 – Arlington, Sussex)

Henry White (46 – Brighton, Sussex)

Mary Ann White née Ellis (29 – Brighton, Sussex)

John Vigar (36 – Worth, Sussex)

Elizabeth Vigar née Simmons (33- Worth, Sussex)

For a bit of background: in 1845 the Prime Minister was Robert Peel. On 15th March the first University Boat Race took place and on 1st May the first cricket match as the Oval was played. The rubber band was patented and the last fatal duel between two Englishmen was fought on English soil. Potato blight in Ireland saw the start of the Great Famine.

The Gesture of Mourning

Graveyards and cemeteries have always fascinated me. The feeling I have when entering them, is much the same as when I enter a museum, a sense of calm mixed with expectation as I wonder whose story or stories I’ll encounter.

Graveyards are archives; the headstones, documents on which we find the names and dates of those who’ve gone before us. But they are much more than that.

My family tree is an archive, one currently comprising almost 1,000 individuals. Poring through documents (albeit ones which are digitised), I discover names, locations and dates, much as you do when walking through a graveyard.

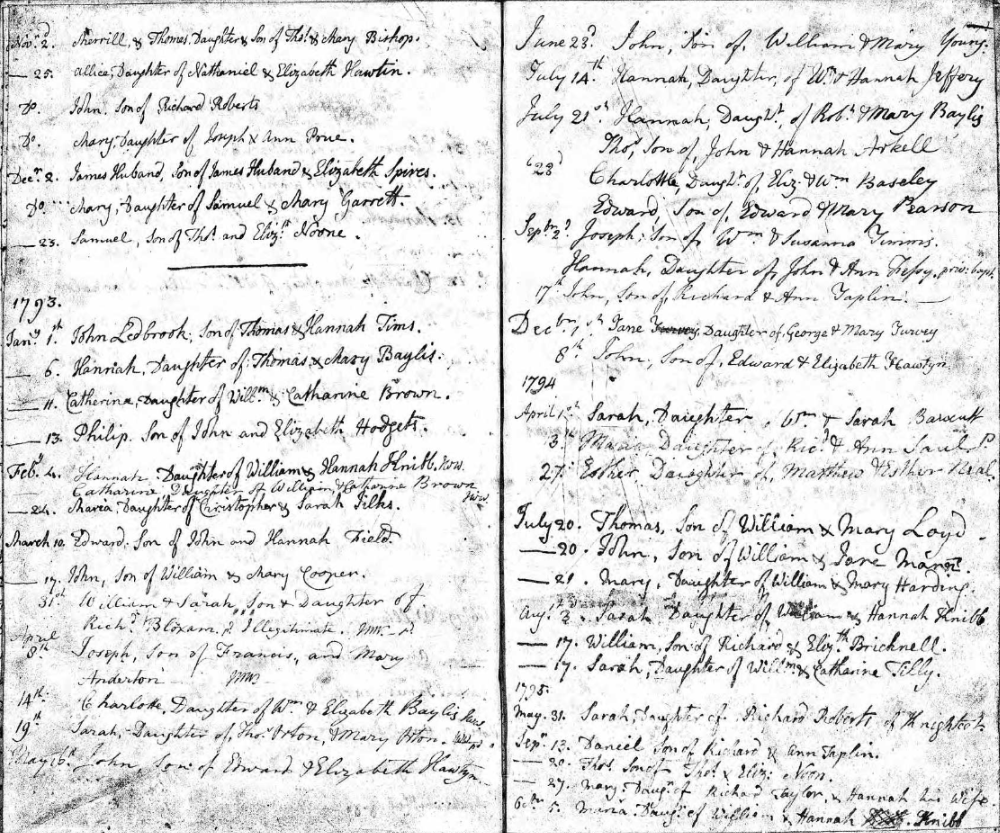

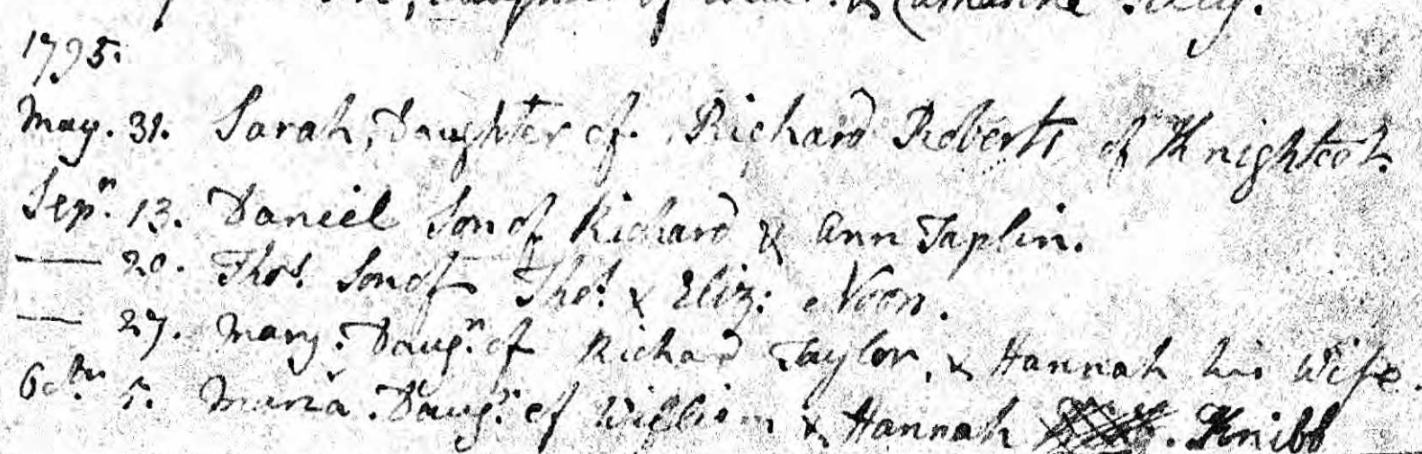

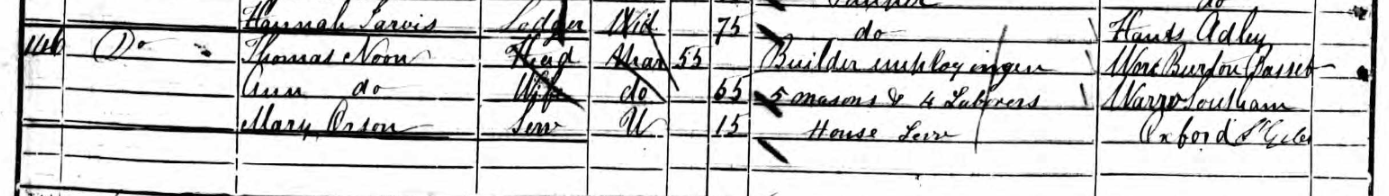

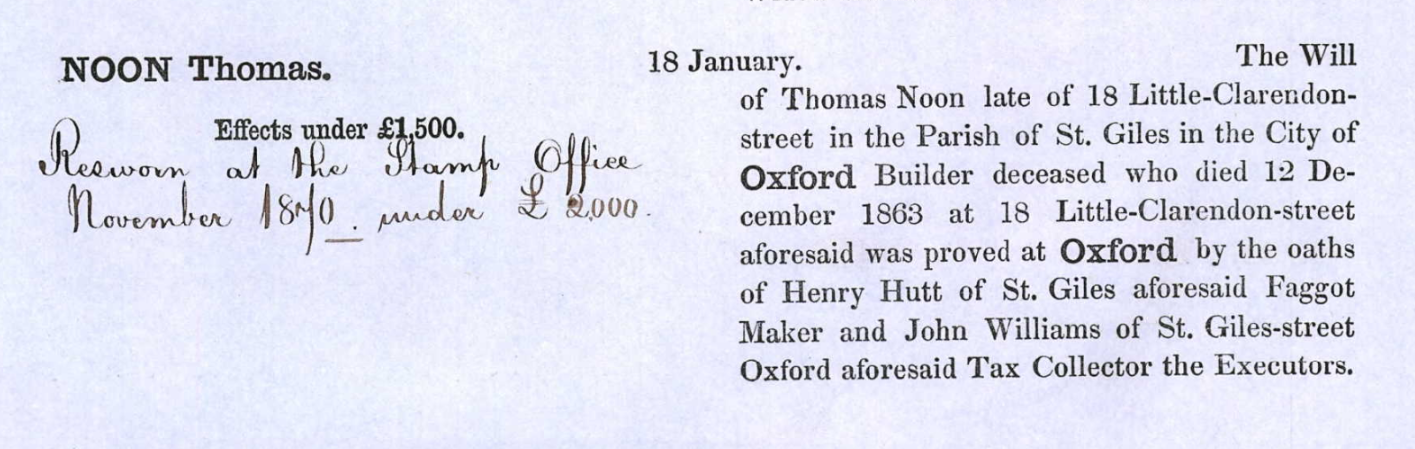

Thomas Noon was my great-great-great-great-uncle. He was born in Burton Dassett, Warwickshire in 1795. He was baptised there on 20th September.

At some point between 1824 (the birth of his daughter Betsy) and 1830 (the birth of his son Thomas) he moved with his family to Oxford.

In 1841 Thomas spent census night away from Oxford, but we find him in 1851, along with his second wife Ann.

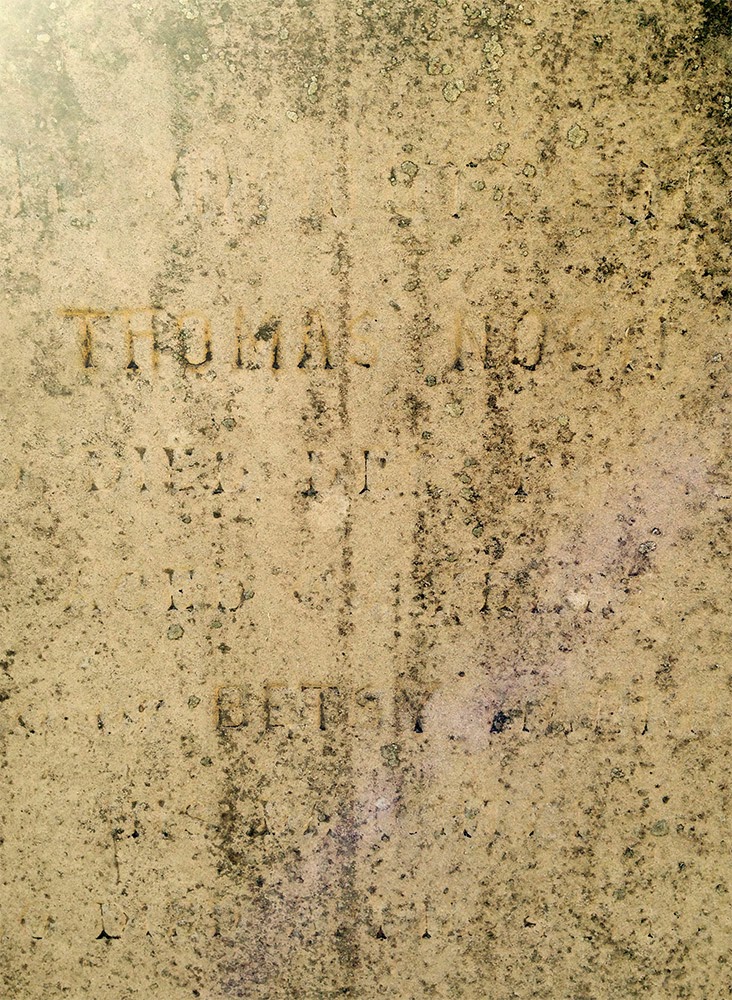

By this time Thomas had already buried his first wife Mary (1832 or 1840) and their three daughters – Emilia (1837), Eliza (1846) and Betsy (1850). In September of this census year, Thomas would also bury his son, killed in a train crash at Bicester. In 1852, tragedy would strike again when his brother Elijah killed his own wife with a sword at their house in Jericho.

Thomas died in 1863 at his home in Little Clarendon Street.

Through archive sources we can piece together his life, in censuses, baptism records, probate records and newspapers.

As we consider his terrible losses, we can sympathise with him but standing at his grave, the one he shares with his son Thomas and his daughter Betsy, that sympathy turns to empathy.

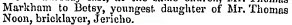

Like the name Thomas Noon, found in the documents described above, we find the name on his gravestone (below), weathered and worn to almost nothing (NB the name Thomas Noon and Betsy have been enhanced).

I can trace his name with my finger, and as I stand there, looking down at the grave, everything changes. I might be thinking, but my body is mourning.

First Betsy and then Thomas Jr were buried in that very grave over a decade before their father. How many times in those intervening years did Thomas stand where I was standing, looking down at that same patch of ground, thinking of his children? It’s as if, standing there over 150 years later, with the bearing of a mourner, I not only find Thomas within my imagination; I find myself within him too.

I can imagine him there, listening as I can to the wind in the trees. He sees the same late-winter sun and feels its warmth on his face. I can, as I have done, read about his children and their untimely deaths. I can read about him. But standing at their grave, my imagined versions of them are augmented by the gesture of my body.

They move in that space where the boundary between imagination and memory is blurred.

Thomas Noon’s Grave

I’ve just been to visit the grave of my great-great-great-great-uncle, Thomas Noon (1795-1863) in St. Sepulchre’s cemetery, Jericho.

Buried with him are his children, Betsy Markham née Noon (1824-1850) and Thomas Noon (1830-1851) who was killed in a train crash at Bicester.

Not far from the cemetery is Freud cafe, once St Paul’s church and the place where Eliza Noon married William Cartwright (1842) and Betsy Noon married Thomas Markham (1844).

Thomas Noon (1795-1863)

Having scanned the pages of Jackson’s Oxford Journal for more information on my great-great-great-great-uncle Thomas Noon, I decided to Google his name whereupon I came across the St Sepulchre’s website which contains a great deal of information on him and his family (St. Sepulchre’s being the cemetery in which they are buried).

I knew a little about Thomas (see The Victorians) such as the fact his son – also Thomas – was killed in a train accident in Bicester in 1851, but I didn’t realise just how much his family suffered in the few years before and after.

Thomas was married to Mary Flecknoe in Daventry on 14 August 1820. Their children included:

Eliza Noon (born 1821)

Betsey Noon (born 1824)

Thomas Noon (born 1830)

Emilia Noon (born 1832)

Mary Noon died before 1841 and there are, according to the St. Sepulchre’s website entry two possible burials:

Mary Noon who died at the age of 36 in 1832 (buried in St Thomas’s churchyard on 29 November), and Mary Ann Noon, stated to be of Jericho, who died at the age of 39 in 1840 (buried at St Peter-in-the-East churchyard on 3 May).

My hunch would be that our Mary Noon is the first of these. I can’t quite see why she would be buried in St. Peter-in-the-East, even though it states that that particular Mary was of Jericho. Given the date of 1832 – the year Emilia was born – it could be she died in childbirth. It would appear that Emilia herself died in 1837.

Two of Thomas’ daughters were married in the early 1840s at St. Paul’s church, which is now Freud’s cafe.

On 13 January 1842 at St Paul’s Church, Eliza Noon married William Cartwright, a coal dealer. They had both been living in part of the same house in Clarendon Street, and Eliza was described as being the the daughter of Thomas Noon, publican.

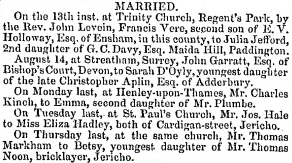

On 15 August 1844 at St Paul’s Church, Betsey Noon married Thomas Markham, a tailor, born in Oxford in c.1820. Both were described as being of Clarendon Street, and their marriage was announced in Jackson’s Oxford Journal.

Then came several tragic years for Thomas Noon.

Eliza disappears after the 1841 census, and may be the Elizabeth Cartwright who died in the Jericho district at the age of 24. She was buried in St Giles’s churchyard on 25 January 1846.

Betsey died 4 years later, at the age of 26 and was buried in St. Sepulchre’s.

A year later, Thomas (Jr) was killed in a train crash at Bicester. He was buried with his sister, his funeral described in Jackson’s Oxford Journal.

The following year, 1852, his brother, Elijah, killed his wife in Jericho. Thomas died in 1863 and was buried in the same grave as his son Thomas and his daughter Betsey.

Lines Drawn in Water

The following passage is taken from ‘The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot’ by Robert Macfarlane. In a chapter on water he writes:

“The second thing to know about sea roads is that they are not arbitrary. There are optimal routes to sail across open sea, as there are optimal routes to walk across open land. Sea roads are determined by the shape of the coastline (they bend out to avoid headlands, they dip towards significant ports, archipelagos and skerry guards) as well as by marine phenomena. Surface currents, tidal streams and prevailing winds all offer limits and opportunities for sea travel between certain places…”

This reminded me of some work I did on my ancestor Stephen Hedges who was transported to Australia in 1828. In particular I thought about the route The Marquis of Hastings (the ship on which he sailed) took from Portsmouth to Port Jackson (Sydney) which I mapped using Google Earth and coordinates written down in a logbook by the ship’s surgeon, William Rae.

Macfarlane also writes:

“Such methods would have allowed early navigators to keep close to a desired track, and would have contributed over time to a shared memory map of the coastline and the best sea routes, kept and passed on as story and drawing…

Such knowledge became codified over time in the form of rudimentary charts and peripli, and then as route books in which sea paths were recorded as narratives and poems…

To Ian, traditional stories, like traditional songs, are closely kindred to the traditional seaways, in that they are highly contingent and yet broadly repeatable. ‘A song is different every time it’s sung,’ he told me, ‘and variations of wind, tide, vessel and crew mean that no voyage along a sea route will ever be the same.’ Each sea route, planned in the mind, exists first as anticipation, then as dissolving wake and then finally as logbook data. Each is ‘affected by isobars, / the stationing of satellites, recorded ephemera / hands on helms’. I liked that idea; it reminded me both of the Aboriginal Songlines, and of [Edward] Thomas’s vision of path as story, with each new walker adding a new note or plot-line to the way.”

One of the things I like about William Rae’s logbook of the journey aboard the Marquis of Hastings is the description of the weather. The world aboard a prison ship in 1828 is far removed from our experience, but we know weather and can therefore use his descriptions to bridge the gap between now and then; moving from – to use Macfarlane’s words – “logbook data” through “dissolving wake” and “anticipation,” all the way back to “planned in the mind.” The description of the weather therefore becomes a poem of sorts, echoing what Macfarlane writes above; how sea paths become narratives and poems, allowing me to step back into the mind of my ancestor.

Fresh Breeze. Mist and rain.

Strong Breeze. Cirro stratus. Horizon hazy.

Hard gale & raining. Heavy Sea.

Hard rain & Violent Squalls. Hail & rain.

Sail

Carrying on with the work I did in Australia, I’ve spent the last couple of days videoing the canvas ‘sail’ that I made there, which was itself made from the pattern of several walks made around Newcastle, NSW. This work (‘Repaired Sail of HMS York (1828)’) is in many respects linked to a piece I made for my third Mine the Mountain exhibition called ‘Old Battle Flags‘ and is about the feel of the wind – the wind being something which although one may read about in history (particularly in the context of sailing) one can only experience in the present (of course the same could be said of everything else, but in light of the theme of this residency, the wind is especially pertinent).

This piece is about the disparity between language and experience. The wind we feel today is the same wind that’s blown over – and indeed through – the centuries and millennia. In winter the wind may blow from the east, from the vast and distant land of Siberia – a place well beyond the horizon but nevertheless a place which exists all the same.

The sail is made from my own past experiences, and the wind a reminder of movement in the past – that which is missing from the pages of history. It’s also about the everydayness of the past – something which we take often for granted like so much else but which is integral to our experience of the world.

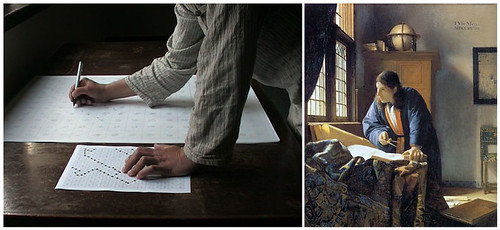

The Geographer

Birds and Words

The photographs of dead birds which I took on Newcastle beach are particularly poignant; the lifeless bodies which had once soared high in the sky above are analogous with lost moments in time and, indeed, with the photograph itself. Dying out at sea, the birds had been washed up on the beach, joined in a line marked by that of the tide, rather like the words in my sketchbook, joined by the trace of the line of a walk.

Putting the two together seems to make sense; the words of the walks referring to moments which once lived and which in the instant they were written down fell to the ground like the birds themselves. With every reading they are as those birds washed back up on the beach, joined again by a line – this time, the act of reading in sequence, or of reading them out loud.

Return to England

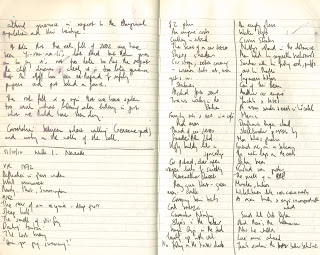

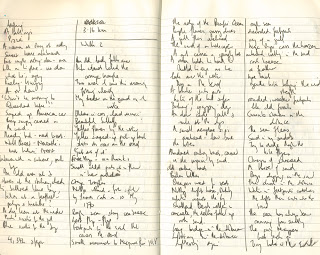

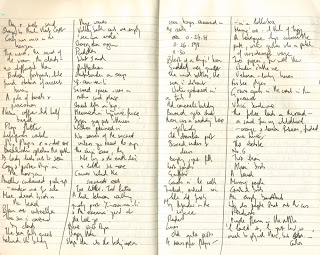

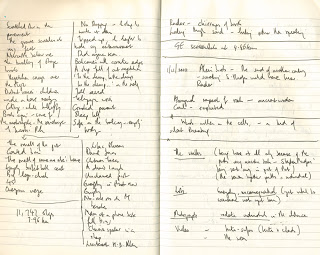

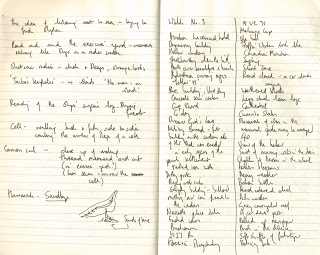

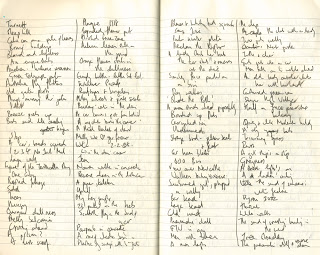

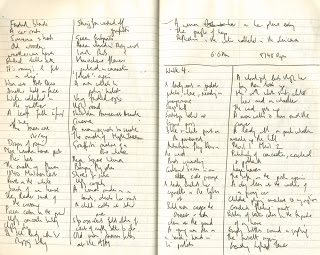

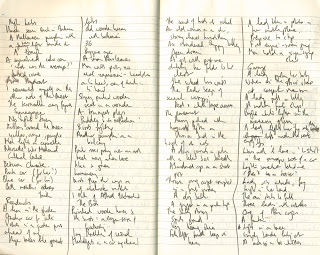

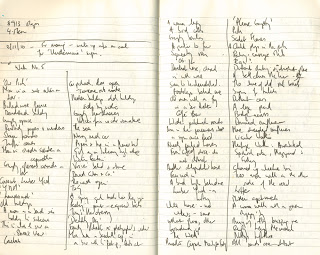

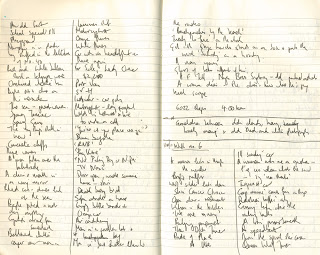

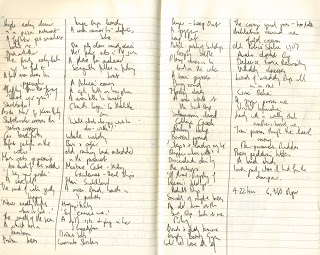

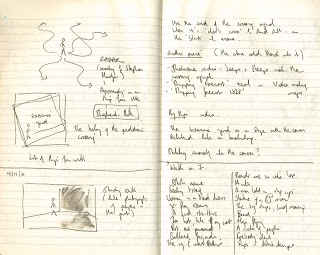

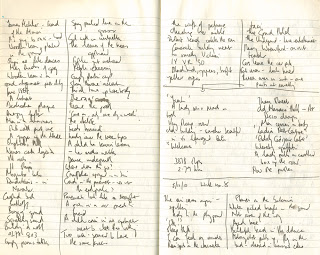

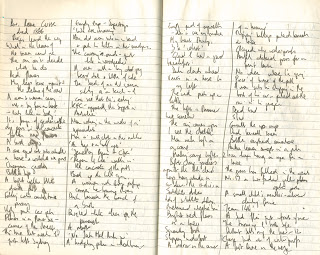

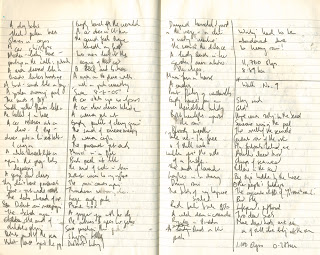

Since returning to England this morning after my residency in Australia, I’ve been looking at my notebook, and feel it’s worthwhile putting the pages up on, in particular those relating to the walks I did. So reproduced with this blog are those pages, written as I was walking (such is why the handwriting is atrocious whereas normally its little better than poor).

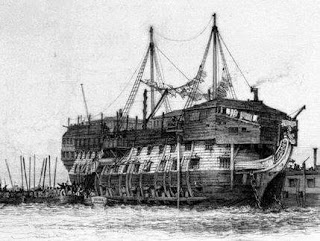

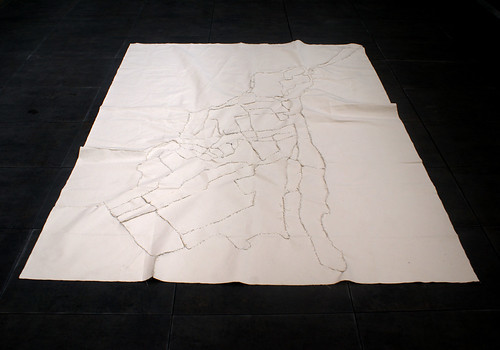

Repaired Sail of HMS York (1828)

Yesterday, I finally finished stitching together the canvas pieces for a workI have tentatively called Repaired Sail of HMS York (1828), refrerring to the prison hulk on which Stephen Hedges was incarcerated before being transported to Australia. The hulk was a demasted ship and on contemporary images (such as that below) one can see how clothes were strung across the ship, almost as if replacement sails themselves.

This piece also alludes to an earlier work of mine called ‘Old Battle Flags‘ which I exhibited as part of my recent Mine the Mountain exhibition. This work – Repaired Sail of HMS York (1828) – was made in response to the old battle flags one finds sometimes hanging in cathedrals. As I wrote in a text accompanying the work:

“Whenever I see them, hanging from their poles, still and lifeless, I think of the wind that would have once shaped them, a wind which would have once blown and turned the pages of history as it was being written. It reminds me that the flags had a place in what was then the present, rather than a scripted, preordained past. I can remember as a child, sitting on the beach when the weather was less than clement, when the wind whipped the sand, drilled the waves and flapped the canvas of the deckchairs. These deckchairs on display still have their colours, and in the main, their shape, but now they are broken; metaphors for times which cannot be revisited.“

The flags hang lifeless without the wind – the past hangs lifeless too. HMS York in this sense is a metaphor for the past – demasted and without a sail, lifeless almost, a prison for the past which in its own present criss-crossed the globe. To re-witness that past we need to see it move again, to catch the wind: we need a new sail.

The sail in this work is made of canvas, and is derived from a pattern made from data recorded on a GPS. The data itself represents a series of nine walks made during the first week or so of the residency here in Newcastle, NSW. As I have discovered through my work over the last few years, walking and being in a particular place and experiencing the everydayness of a place, is vital in our understanding of associated historical events. It is relevant therefore, that this ‘sail’, made to catch the wind and ‘move’ HMS York once again, is constructed from a series of walks.

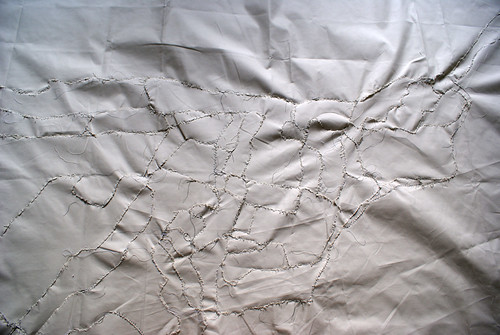

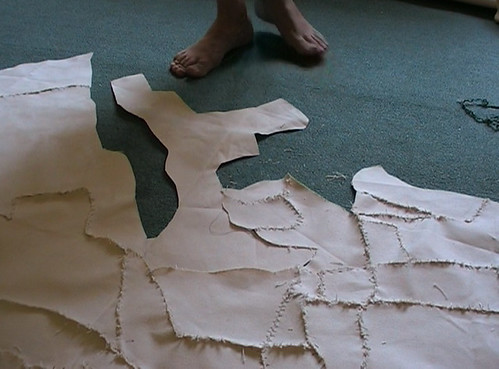

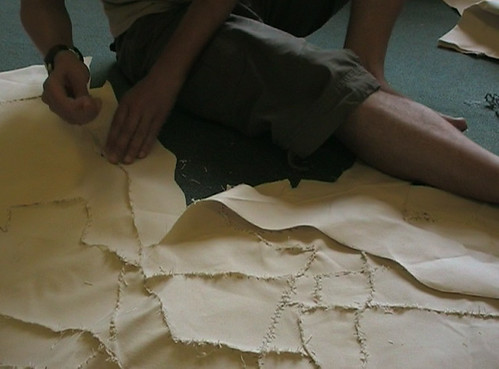

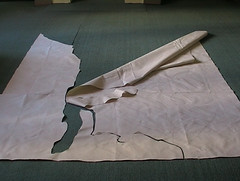

Below are a number of images of the sail.

Often, it’s the reverse side of a piece like this which proves to be the most interesting, and indeed the most aesthetically satisfying. This particular canvas is no exception. When I turned it over and laid it out, I found the loose threads and knots particularly interesting. Perhaps they remind me the cut lines of past lives or the unwritten lines of text of which, for the most part, history is comprised. Below are images of the reverse side of the canvas.

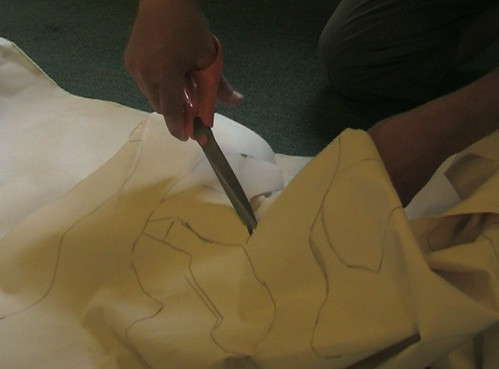

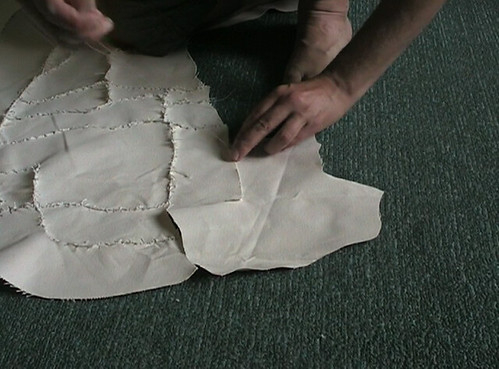

Cutting and Stitching III

Cutting and Stitching II

I’ve made a lot of progress over the last couple of days with video work and with the sticthed map of walks I’m creating, the title of which will be something like ‘The Lost Sail of HMS York’ referring to the prison hulk on which Stephen Hedges was incarcerated in 1828 prior to being transported to New South Wales.

Having cut the templates and pinned them to the canvas, I then drew around each one directly onto the canvas so that I could begin cutting them out and stitching the piece together. To make things easier I will cut each piece as and when I need it so that I don’t get lost as regards where the pieces are meant to go.

The followng stills are taken from further documentary footage I’ve filmed of the process.

Cutting and Stitching

A busy day today working on a piece tentatively titled ‘Hammock’ and another which has yet to acquire even a working title. The hammock piece (shown in the photograph imemdiately below) alludes to when sailors died at sea and were sewn up in their hammocks before being cast into the water. The stitching on this particular hammock/body bag is the line recorded on my GPS when I walked the route Stephen Hedges walked from Radley House to Oxford in January 1828.

The hammock no longer has a body inside but what is left is the line. In many respects, the body inside was never meant to be that of Stephen, but rather his life in England, cast overboard along with his clothes when he entered the Prison Hulk York in Portsmouth following his conviction.

I want to dirty-up the canvas a bit and am thinking of taking it down to the sea tomorrow and videoing it lapping at the shore with the waves; something which would lend the work greater resonance.

The images below show the piece being made.

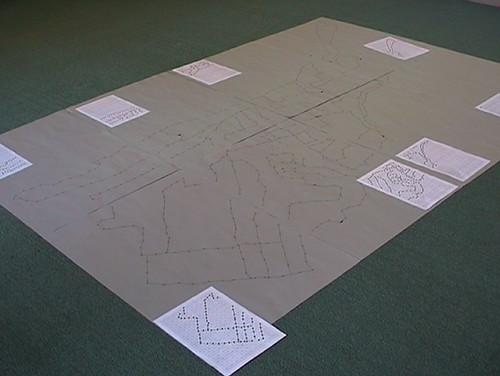

The following images are taken from the second, much bigger piece, which is a canvas comprising all the walks I have made in Newcastle NSW. The walks have been transferred to tracing paper (see Making the Map) and have now been cut up and pinned to the canvas ready for the material to be cut.

The images below are taken from documentary footage of the process.

The map itself isn’t so easy to photograph, but I like the way it looks in its current state, with the cut out templates and the pins. Ideally I would like to inject something of a perfomative aspect into this work, so that the template creation has something to do with the process of tailoring – preparing fabric for an individual.

A Walk of 4,342 Steps

The video-based performance piece I want to make involves my walking around the exercise yard – in this case for about an hour. The ‘Walk of 4,342 Steps’ refers to a walk I did on 31st October (the first walk in a series of 9 made during the residency) and the final video will comprise my walking with details of the walk read out over the top.

The following stills are taken from the video.

As I walked, and as I felt my body tense up and stiffen (in particular my jaw for some reason) I found myself listening to the sounds from outside, coming through the bars in the ceiling. Again this seemed to illustrate my work, as regards the idea of the constrained walk being analogous to history’s relationship with the past, where the wider past can only be ‘glimpsed’ to some degree through the bars.

The Exercise Yard

One of the most interesting spaces in the Lock Up is the exercise yard in which inmates housed in the cells would walk, sit or stand for a period of time. The space has recently been made weather-proof and a floor added to the original floor beneath so as to allow the space to be used for exhibitions and so forth. I wanted to use it in a video-based perfomance piece based on the idea of history and its relationship to the past; the idea that history is in a sense heaviliy constrained in what it can tell us about the world long gone; it is hemmed in, not free to roam, but follow a prescribed path based on the sources available to us today.

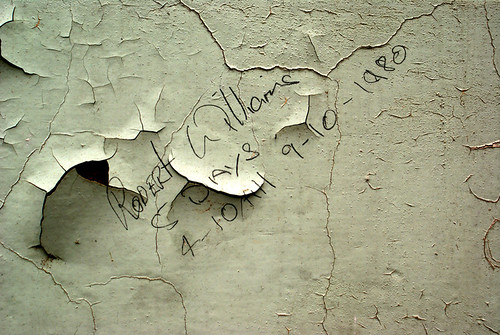

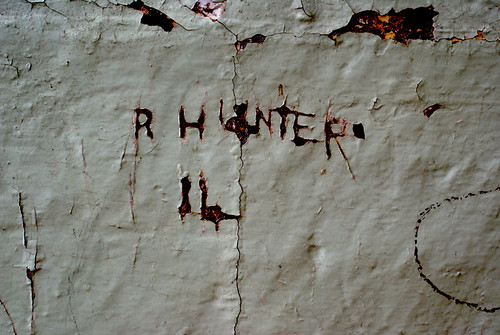

Before working on the piece (which would involve an hour’s walk around the yard), I photographed the walls, all of which have amazing textures redolent of the passage of time: peeling paint, cracked surfaces, palimpsests of paintwork and decay, as well as the inscriptions of prisoners scratched into the walls.

Below are some details from the exercise yard.

Making the Map

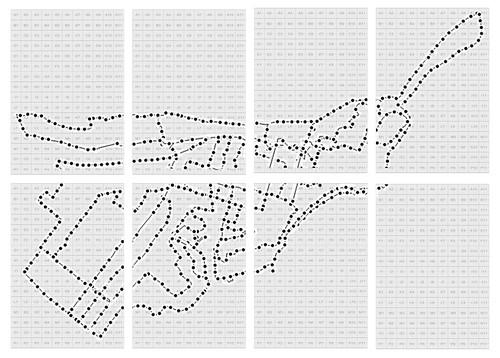

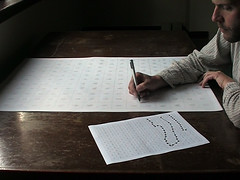

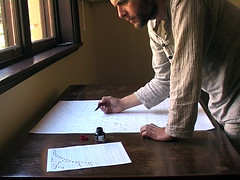

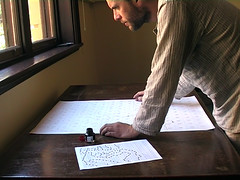

Having completed all the walks the next task is to tranfer them all to tracing paper so that templates can be cut and the map re-made on – or rather with – canvas. Taking the GPS plan, I divided it up into 8 segments, each of which I printed out onto A4 pieces of paper.

I then began scaling each piece up onto A1 heavyweight tracing paper, first marking all the dots and then joining them together. I would like to develop this whole aspect of the work, using the metaphor of sea-faring and map-making generally. Given time constraints however, the process will have to remain absent of any ‘performative’ aspect.

Having plotted the position of the dots, I then set about drawng in the lines.

Once copied, I joined the sheets together to make the fullsize version of the map which is now ready to be cut into templates.

Light

This evening I started filiming – for documentary purposes – my work on creating the templates for the ‘sail’ which I will start to sew soon. As I set up the video, I noticed, in the corner of the room, a patch of light on the wall and the floor. It reminded me of the paintings of Hammershoi, such as the image below which I wrote about in a previous blog entry back in March this year.

I put the video camera on the patch and started filiming for a couple of minutes, but as I watched the subtle changes in light I decided to leave it running until the tape ran out some 50 minutes later. The results were rather beautiful; an illustration of the passing of time, the end of a day and the the ‘nowness’ of the present – something which Hammershoi reveals beautifully in his paintings. Although painted at the beginning of the 20th century, the patch on the light keeps them very much a part of the present – the shape of the light cast by the window is something with which we are all familiar.

The stills below – taken from the video – show the light over a period of about 50 minutes.

Dead Birds and Footprints

Yesterday I walked along Newcastle Beach and discovered, as I’d seen before, dozens of dead birds washed up on the sand. The shape in which the sea had left them was, in many cases, beautiful and so I began to photograph them.

As I did so, I also became aware of the many footprints left in the sand, all different shapes and sizes, and so I started to photograph those as well, and in doing so, began connecting one with the other.

To see all photos, visit my Flickr pages.

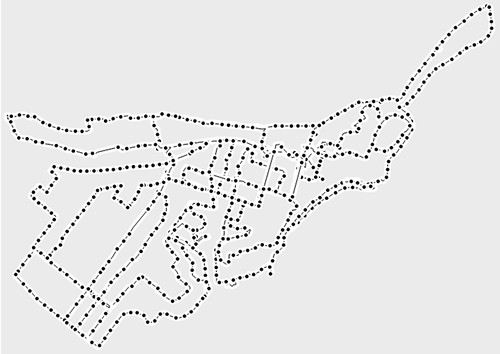

Completed Walks

During the first week of this residency, I carried out a number of walks, the routes of which I recorded using GPS.Collecting all these walks together, I created a map of all the walks which can be seen in two images below. The first shows the pattern as revealed in the GPS software, the second in Google Earth.

The next phase for this work is to divide the the first image into segments, each of which can then be tranferred to heavyweight tracing paper, after which the lines will be cut and the pieces left behind (i.e. the spaces in between the walks) transferred to canvas.