The Past is Time without a ticking clock. A place where paths and roads are measured in years. The Present is a place where the clock ticks but always only for a second. Where, upon those same paths and roads we continue, for that second, with our existence.

In 2006 I visited Auschwitz-Birkenau and since then have visited camps at Bełżec, Majdanek and Natzweiler-Struthof, as well as the battlefields of Ypres, Verdun and more recently, The Somme. All these sites present the visitor with numbers: 1.1 million dead at Auschwitz-Birkenau, 500,000 at Bełżec, 79,000 in Majdanek. At the start of the Battle of the Somme, on 1st July 1916, British and Commonwealth forces sustained 57,000 casualties, with almost 20,000 men killed in action on that day alone. These are all horrific statistics, but numbers rather than people and over the course of the last few years, I’ve looked for ways of identifying with the individuals behind the grim tolls. The tolls are only estimates, and the individuals to whom they allude have become themselves ‘estimates of existence’. Most have left nothing behind; no name, possessions, or photographs. Photographs, where they exist, are often nameless, names on graves are faceless, so how can we know them at all?

One of the most difficult things about my visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau was walking out the gate, performing an action that more than a million people could only ever dream about – if they had the time; most were killed within hours of their arrival. At Bełżec, the memorial to the dead is – in the main – a walk around the perimeter of where the camp once stood. During my visit in 2007, I recorded the walk using a GPS receiver and the fact that I, as an individual, one of several billion people on the planet, could be tracked in this place where half a million people perished, proved particularly resonant. The concept of walking as a means of remembering began to take hold in my work, evolving over time to become a means of empathising – in some small way – with those who’d perished.

In the book Walking, Writing and Performance by Deirdre Heddon, Carl Lavery and Phil Smith, artist Carl Lavery states the following:

“…pedestrian performance is a mode of resistance against the acceleration of the world, a desire, on the part of performance makers, to re-humanise space by encouraging spectators to experience the environment at a properly human pace, the bodily beat of three miles per hour. Implicit in this argument is the belief that walking is conducive to the production of place, a perfect technique for merging landscape, memory and imagination in a dynamic dialogue. Or as Michel de Certeau would have it: ‘The act of walking is to the urban system what the speech act is to language…’.”

In the passage quoted above, I was struck by the idea, as Lavery puts it, of “encouraging spectators to experience the environment at a properly human pace.” Merging landscape, memory and imagination (for which purpose, according to Lavery, walking is the perfect technique) has become central to my work. It’s also something I’ve done quite naturally since I was a child. For me, places have always been a conflation of these things, and as such, quite unique to me.

When I visit historic sites, landscape, memory and imagination merge to create something akin to what others have termed post-memories; ‘memories’ of events of which we can have no real recollection – in particular events that happened before we were even born. How this happens is something which has interested me throughout my research. A kinaesthetic engagement with a place, and our sense of the present are, it seems, both important in this regard.

Finally in the paragraph quoted above, I was struck by the words of Michel de Certeau; the idea that ‘the act of walking is to the urban system what the speech act is to language,’ reminded me very much of what I’ve read before in the work of Christopher Tilley, who in his book The Materiality of Stone – Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology, writes that ‘If writing solidifies or objectifies speech into a material medium, a text which can be read and interpreted, an analogy can be drawn between a pedestrian speech act and its inscription or writing on the ground in the form of the path or track.”

The idea of a path as ‘text’ is something which appeals to me; the notion that as we walk we ‘write’ ourselves in the landscape has a particularly poetic resonance. In his book Lines, a Brief History, Tim Ingold writes that “human beings leave reductive traces in the landscape, through frequent movement along the same route…”. The Old English word writan he tells us, meant to ‘incise runic letters in stone,’ and a correlation can therefore be drawn between the act of walking and writing; a path is something written over years by many different people, incised into the landscape.

Just as when we speak we re-use the same words spoken over centuries – for example fragments of long forgotten conversations – so when we walk, we re-use fragments of other people’s ‘texts’, ‘written’ into the landscape. In this sense, we speak with our bodies words that other bodies have spoken or written before us. As Ingold notes: “retracing the lines of past lives is how we proceed along our own.”

In 2007, the year before she died, my grandmother told me about her childhood in Wales. The following is an extract from that conversation in which she describes her father, Elias Jones, who died in 1929, aged 47, as a result of working in the mines:

‘I can see him now because he went up our garden over the road and the mountain started from there up… and he’d go so far up and he’d turn back and wave to us…’

On visiting Hafodyrynys, the village where my grandmother grew up, I walked up the ‘mountain’ she’d described and followed the path my great grandfather would have taken to work in the mines at Llanhilleth. On top of the hill I turned and looked back down at the garden, imagining my grandmother and her siblings waving back at me from the past. Further on, I stood and looked at the view, rolled out all around me. A hundred years ago I thought, when I did not exist, he would have seen the very same thing. A hundred years later, long after his death, I found myself – through being in that place – identifying with him: I’d found him on the path – one which would in time lead to my being born.

Elias Jones, through frequent movement along that path had written himself into the landscape. A hundred years later, I was – through articulating my own presence through walking – reading part of that text; speaking with my own body his simultaneous presence and absence. In many ways, I was speaking my own presence and absence too.

During that visit, I realised that as well as being a product of the ‘genetic text’ passed down the generations through a myriad number of genealogical lines, we are as much the consequence of pathways walked by every one of our ancestors. DNA is text – a kind of narrative sequence – and the paths which have led to our individual births are a vast text written across the landscape: self and environment, to borrow from Lavery, are umbilically connected.

People are therefore, in a sense, places, and in his book, Lavery quotes Mike Pearson, a performance maker and theorist who states that: “just as landscapes are constructed out of the imbricated actions and experiences of people, so people are constructed in and dispersed through their habituated landscape: each individual, significantly, has a particular set of possibilities in presenting an account of their own landscape: stories.”

Another passage in the book which interested me was that regarding the geographer Doreen Massey. Lavery writes how she offers a ‘conception of space that is interrelational, multiple and always under construction. In her book, For Space, she describes it [space] as ‘the dimension of multiple trajectories, a simultaneity of stories-so-far’.”

I like the idea of space being a ‘simultaneity of stories-so-far’, and it interested me insofar as it rang a bell with some thoughts I’d had previously regarding our own perception of the past. The following is taken from a piece I wrote on the nature of history:

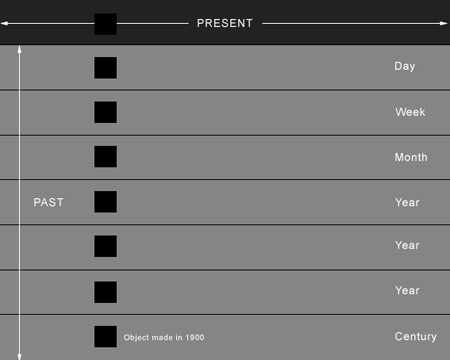

The past is often perceived much like the strata of a rock-face, wherein successive layers of geological time can be seen. We see the past as being built from the ‘ground up’ day upon day, year upon year, century upon century, like bricks in a wall. The problem with this ‘model’ however is that it makes the past difficult to access, the lines dividing each and every moment become like barriers inhibiting our movement between one and the other, particularly where one part is stacked so far below our own in what we perceive as being the present day. Another problem with this way of perceiving the past is that the layers necessarily contain objects, buildings and landscape features which, because of their age, appear in several different layers almost as if they were different things. For example, an object made a 100 years ago, would appear in each of the layers in the diagram below (see Figure 1). It’s rather like someone creating an animation, who draws the same scene a thousand times because it appears in a thousand frames, rather than using the same picture throughout them all.

Figure 1

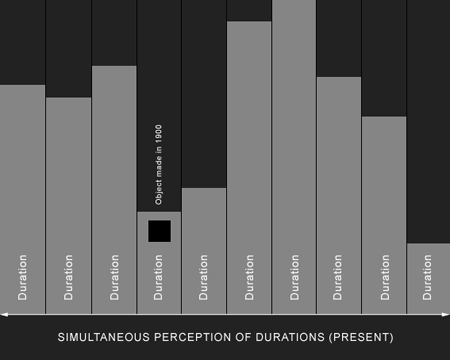

Whilst thinking about this and while considering the fact that any extant object, building or landscape feature, no matter what its age is always present, I realised that a better model for perceiving the past is one which turns the model above on its side – if not quite its head. Subsequently (see Figure 2), what we have is not a series of horizontal strata representing stacked moments in time (days, months, years, centuries etc.), but concurrent vertical lines, or what I have called ‘durations’ where each duration is an object, building or landscape feature and where the present is our simultaneous perception of those that are extant (of course, in the case of buildings, individual ‘objects’ can also contain many separate durations).

It was Bill Viola who said that ‘we have been living this same moment ever since we were conceived. It is memory, and to some extent sleep, that gives the impression of a life of discrete parts, periods or sections, of certain times or highlights’. Similarly we can say that every object, building or landscape feature has existed in one continuous moment and that it is to some extent the passing generations which gives the impression of the past as being a series of ‘discrete parts, periods or sections, i.e., the perceived layers or strata of our previous – first – model.

Figure 2

These ‘durations’ as I have described them, are indeed ‘stories so far,’ which move, as if they are being told, at the speed of walking – at a ‘properly human pace’ as Lavery puts it.

Returning to the idea of walking as writing, it’s true to say that we don’t always leave a physical trace of our presence when we walk – or at least a visible, physical trace. But, poetically speaking at least, we do leave something behind and this something is often augmented by objects, buildings or landscape features which are contemporaneous with past individuals.

Whenever I visit sites of historic trauma (death camps and the battlefields of World War One), even if they’re empty, I feel as if they’re full; not in a spiritual or pseudo-spiritual sense, but physically, as if they’re full of sculptures. Sculptor Antony Gormley describes his work as ‘confronting existence’ and that, in part, is what we do in places such as Auschwitz; death is, after all, another kind of existence. Walking itself is a means of confronting existence, being as it is a line drawn between absence and presence – just as I’d found in Wales.

“Part of my work,” Gormley writes, is to “give back immanence to both the body and art.” For archaeologist, Colin Renfrew, Gormley is “speaking of the existence of the individual, and the coming into being and self-awareness of the individual as the inhabitant of his or her body.” In reading these quotes, I began to see that the sites of trauma I’d visited, as well as those places relevant to my own family history, were full of what I can only describe as invisible sculptures – sculptures of absence, the physical presence/immanence of all who’ve gone before.

Gormley’s work comprises, in part, casts of his own body which reminds Renfrew of the bodies found in Pompeii; men, women and children frozen at the moment of their death almost 2000 years ago. Buried in ash, the spaces which had once contained their bodies remained after the bodies had decomposed, allowing archaeologists, to use them as moulds by pouring plaster into the cavities.

In light of this, I was reminded of the work of Christopher Tilley, who in his book, ‘The Materiality of Stone, Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology’ writes: “The painter sees the tree and the trees see the painter… in a manner comparable to that in which the mirror ‘sees’ the painter: that is, the trees, like the mirror, let him become visible: they define a point of view on him which renders visible for him something that otherwise would remain invisible – his outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence… The trees and mirror function as Other.”

Just as the trees function as ‘Other’ therefore, so must the sun, the stars, the clouds, hills, mountains, the sea, rivers, the wind, the rain and so on. And in a sense, what Tilley is describing as Other, which ‘renders visible for him… his carnal presence,’ is a sense of being present in the present-day world.

In the book Walking, Writing and Performance, Lavery writes:

“…during… Mourning Walk I was aware of living more in the past than in the present. However at no time did this immersion in memory result in psychic saturation or disintegration. The natural world – the world of trees and stones – was stubbornly present and insisted on maintaining its autonomy and distance.”

When trying to access the past through walking, an awareness of the present – of being present in the world – is vital, and the natural world – the world of trees and stones – does that for us. Understanding the fact that the past was once the present, helps us in some small way to empathise with those lost to the past.

The present moment is a space, one which lasts only for a second – a space comprising the simultaneity of what Doreen Massey calls ‘stories so far’ or what I have called ‘durations’. And it’s in that space that life happens. Behind us and in front, beyond the physical boundaries of that second we are absent. The text is written, or yet to be written – the present being the moment of writing. Gormley’s sculptures then articulate this line between presence and absence, past and present.

In that space, in which we continue with our existence, we hear the birds, we see the sun, feel the wind and rain. In that space, all our hopes are held, all our fears and regrets. Into the space we carry our past in the form of memories. It’s the space of the everyday – one which we often take for granted. But it’s a space we share with everyone who’s ever gone before us.

Again, in his book, Lines. A Brief History, Tim Ingold tell us that:

‘…from late Antiquity right through to the Renaissance writing was valued above all as an instrument of memory. Its purpose was not to close off the past by providing a complete and objective account of what was said and done, but rather to provide the pathways along which the voices of the past could be retrieved and brought back into the immediacy of present experience, allowing readers to engage directly in dialogue with them and to connect what they have to say to the circumstances of their own lives. In short, writing was read not as a record but as a means of recovery.’

This paragraph has something in common with what I described earlier, the idea that just as when we speak we re-use the same words spoken over centuries – fragments of long forgotten conversations – so when we walk, we re-use fragments of other people’s ‘texts’, ‘written’ into the landscape. Walking becomes a means of recovery, where the past can be retrieved and ‘brought back into the immediacy of present experience’. As on the ‘mountain’ in Hafodyrynys, it’s a means of engaging in a dialogue with those who’ve gone before us, and nowhere is this more keenly felt that in places of historic trauma.

It’s as if when walking through these places, we pick up – at random – the threads of other people’s texts. We tie them together, filling in the gaps with our own story. It’s rather like the film Jurassic Park, where dinosaurs are cloned using DNA extracted from mosquitoes frozen in amber. The gaps in the code are filled with modern frog DNA, creating a ‘modern’ dinosaur. Earlier, I stated that people were as much the product of places, and it figures therefore that places are as much the product of people; that the ‘DNA’ of any place comprises narrative lines laid down by everyone who’s ever been there. When we walk, we create new places based on the present day landscape. Our memory and memories, history and of course our imaginations all have a part to play. Within our imagination, we take with fragmentary strands of the landscape’s own ‘DNA’ (or history) and fill the gaps with our own presence and memory. These constantly created spaces (created then destroyed every second) are unique to us, and yet we share them, in that single moment, with all who’ve gone before us, not as part of a crowd, but as one body and mind.

The ‘stubborn’ presentness which Lavery describes is therefore vital to our empathising with the past, and in many ways the most terrifying thing at Auschwitz was the way the trees moved in Birkenau (Auschwitz II), simply because they would have moved that way during the Holocaust.

The writer Georges Perec once wrote that “the desire to find roots, the determination to work from memories or from the memory, is the will above all to stand out against death, against silence.”

I work from memories and the memory and I’m actively engaged in searching for my roots. Is this then a will to stand out ‘against death, against silence?’

Again, in Walking, Writing and Performance, Lavery writes:

“Is not all writing, all art, a response to a loss of some kind, an imaginative way of dealing with lack? …As I use it, the word recovery has nothing to do with re-experiencing the lost object in its original pristine state; rather, it designates a poetic or an enchanted process in which the subject negotiates the past from the standpoint of the present.”

This act of recovery is just the same as that which Ingold describes, where writing (in ancient times) was read not as a record but as a means of recovery. Walking as a means of ‘reading’ or ‘speaking’ the text of other people’s lives is a way of recovering a moment in the past; an ‘enchanted process’ to borrow from Lavery, where we ‘negotiate the past from the standpoint of the present.’

Empathy with the past therefore and in particular with individuals can be achieved, coming via a kinaesthetic response to the present mediated through memory and our embodied imaginations.