“A single moment suffices to unlock the secrets of life, and the key to all secrets is History and only History, that eternal repetition and the beautiful name of horror.” Jorge Luis Borges

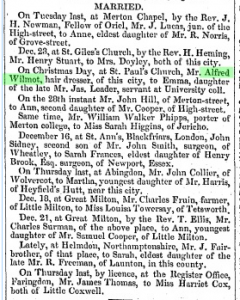

Alfred Wilmot

Having photographed the grave of Henry Sides, I took one of another grave which had caught my eye whilst walking the same path. This belonged to an Alfred Wilmot:

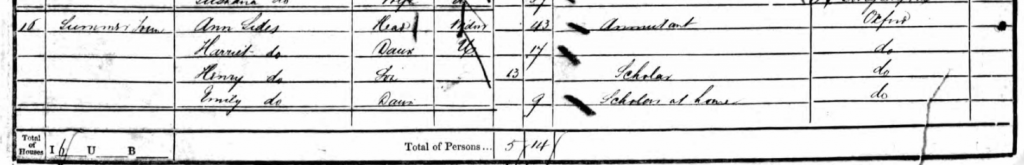

Harriet Sides

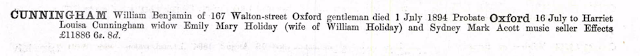

Harriet Sides was the eldest daughter of Henry Sides. Born in 1834 she was married to William Cunningham in 1871 age 37. William Cunningham was born in 1826 in London to a William and Mary Cunningham and in 1861 is shown to be living at 20 Broad Street, Oxford.

In 1881, Harriet and William were living in Kidlington, Oxford with their two children, Clifford (6) and Walter (4). In 1891 they were living at 167 Walton Street, Oxford along with their two children and a servant, Clara Seppury.

William died on 1 July 1894 leaving £11,886 6s 8d in his will – almost £1.4 million in today’s money.

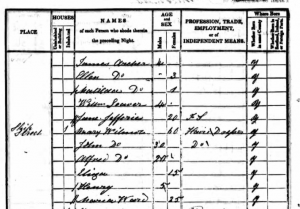

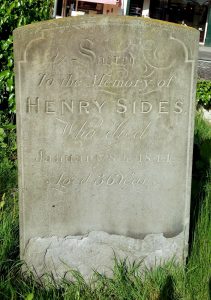

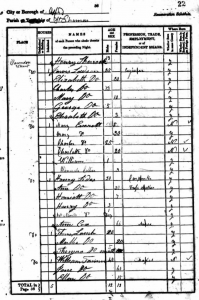

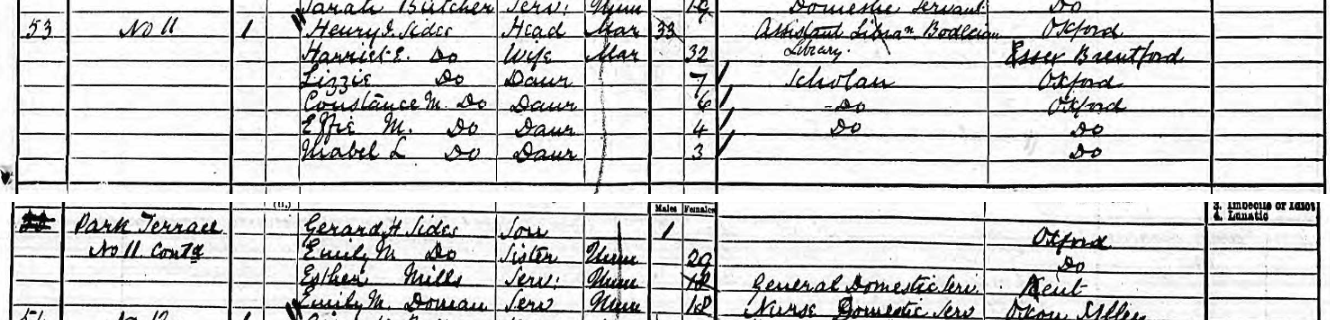

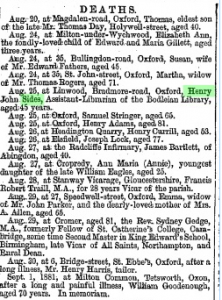

Henry Sides and family

Everyday, on my way to catch the bus after work, I pass by this grave at the edge of the path which cuts through St Giles churchyard.

Ten years on, in 1881, Henry and Harriet have extended their family still further, with the arrivals of Arthur, Herbert, Gertrude and Archibald. They had moved too, living now in Bradmore Road with a Cook and a Nursemaid. At 42, Henry is still an assistant librarian and partner in a firm of rope makers.

Henry John Sides died on 25th August 1883, aged just 45…

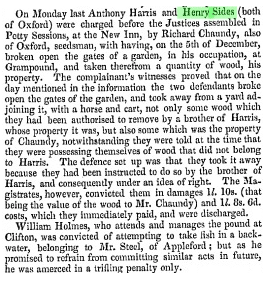

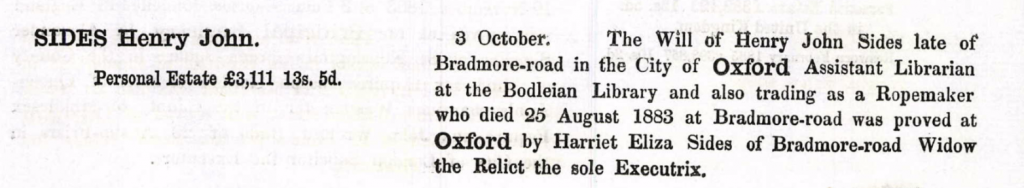

A Victorian Storm

Whilst researching Jackson’s Oxford Journal, I randomly selected an edition from 1842 in which I found the following:

Following on from my last blog and my interest in the perception of time in the past as time passing I’m drawn to this piece which serves, I think, to illustrate the point.

For example, the first line:

“On Wednesday evening last we were visited with one of the most extraordinary storms of thunder and lightning ever remembered.”

Firstly, the words “Wednesday evening last,” pinpoints the storm in terms that are not ‘historical’. It’s not as if we’ve read in a book, “on September 7th 1842, a great storm hit the city.” Rather the event is located in time using a phrase we might use today. It locates the storm in relation to the present – even if that present is September 10th 1842 – and at once feels fresh and contemporary.

Secondly, the phrase “ever remembered,” reminds us, if you pardon the truism, that there was a time before this time. But whereas we know that before 1842 there was 1841 and so on, what this phrase describes is living memory. Again, if we were reading about the storm in terms of its being an historical one, we would know that everyone who experienced it was dead. Reading this article, they are very much alive. Not only that, but the whole of the nineteenth century – and perhaps a part of the eighteen is alive within them too.

It isn’t only this storm which lives within these words, but many others stretching back as far as the late 1700s.

The next description is something with which we have all experienced:

“Shortly after dusk, the lightning appeared in the south and western horizon, and soon became most vivid, blue sheets of lightning following each other in rapid succession, but unaccompanied by thunder.”

That lack of thunder is the punctum of this text. (Ironically, the last time I mentioned punctum in a blog was in an entry entitled ‘Silence‘ about the death of my great-great-uncle, Jonah Rogers.) All the sounds of Victorian Oxford, on that September night in 1842 are contained in that silence. Even within our imaginations, it would seem that the the absence of one sense, heightens all the others. We can sense the approaching storm, feel its presence on the horizon. We can see the muted colours of dusk, muted further still.

Then the thunder comes – “distant peals of thunder” as the writer puts it – which increase until by 9 o’clock, it accompanies every flash. This means of course that the storm was right above the city. The rain falls hard, and with it hail – or “pieces of ice,” which damage numerous properties and the turnip fields of Cowley. By 10 o’clock it was over.

One of the names mentioned in the piece is Sir Joseph Lock whose greenhouse was damaged to the tune of 500 panes of glass. An unpopular man, he built Bury Knowle House in 1800 (the gardens of which feature in another recent blog). Here in Headington, as it was in Cowley, the storm “was frightful” and we can imagine Mr Lock looking out the window of his house as the storm lashed his garden, his face, in the dark midsts of the past, illuminated for a moment by the lightning.

Lydia Stevens (1734-1822)

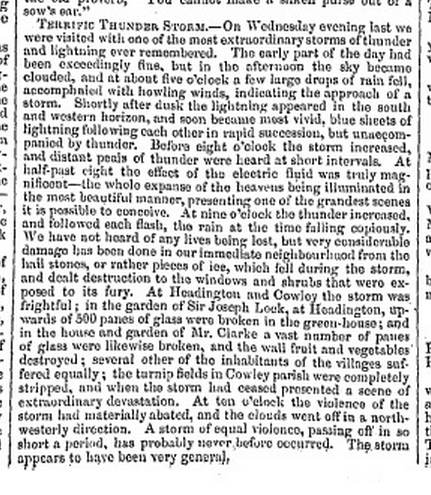

Researching John Stevens in the library today, I found what I’m sure must be his parents. Having looked at the Index of Baptisms for the time around his birth (1811) I found only one person matching his dates. John Stevens was born on 7th October 1811 in St. Aldate’s parish. His parents are given as Samuel and Mary Stevens, and looking at John Stevens’ children, I found that his second born son is named Samuel (his first son is called John). I decided to see if I could locate a Samuel Stevens in the Parish Registers. I couldn’t be sure that he was born in the city but it seemed quite likely. Sure enough I found a Samuel Stevens born on the 4th April 1776, baptised in St. Martin’s (now demolished). His parents were given as John and Lydia Stevens and so I looked for a record of their marriage in the city. Again my luck was in and I found that they were married on March 24th 1764 in St. Mary Magdalen. Lydia’s maiden name was Borton and the witnesses at the wedding were Sam Borton and Mary Stevens. John is described as being from St. Martin’s which is where Samuel was baptised.

At the same time I also wrote the following:

A year or so ago, I started work on a piece of work based around John Gwynn’s survey of 1772. The piece was called (as a working title) ‘6 Yards 0 Feet 6 inches’ based on the measurement of John Malchair‘s home in Broad Street. Having discovered an ancestor – John Stevens – born in the city in 1811, I wondered if there was any chance that one of the Mr Stevens’ listed on the survey was an ancestor of mine? It seemed a long shot but after today’s research I’m rather more optimistic.

If I did have an ancestor in Oxford at the time of the survey and if my research is correct, then that ancestor would be John Steven, the grandfather of the one previously mentioned. I’ve no idea when he was born but I do know that he was married in 1764 and is described as coming from St. Martin’s Parish, where his son Samuel, John Jr’s father was baptised in 1776. One could assume therefore that I did indeed have ancestors living in the parish of St. Martin’s at the time of the survey.

The images below are taken from the survey and show two Stevens one of which might well be my ancestor.

Gwynn fails to include (at least on the copy I have) first names from the survey but within the parish of St Martin’s two Mr Stevens are recorded along with a Mrs Stevens. One can assume however, that those most likely to be mine are the two Mr Stevens mentioned as living in the parish, one in Butcherrow (now Queen Street), the other in North Gate Street (now Cornmarket). The residence in Butcherrow is 7 yards 0 feet and 6 inches. That in North Gate Street is 4 yards 2 feet 0 inches.

Of course more work is required to see if one of these is indeed my ancestor, but I must admit to being very inspired by the prospect.

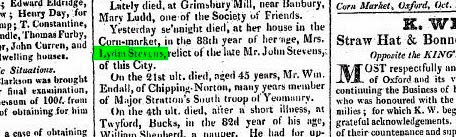

Yesterday, I was looking through Jackson’s Oxford Journal online and decided to search for a number of my ancestors. I’d already done as much with the Hedges side of the family (discovering in the process that they were often in trouble – see ‘The Victorians‘) and decided to check on my maternal side. I searched for Lydia Stevens (my 5 x great-grandmother) and discovered the following from an edition of the newspaper printed on November 2nd 1822:

‘Yesterday se’nnight [a week] died, at her house in the Corn-market, in the 88th year of her age, Mrs. Lydia Stevens, relict [widow] of the late Mr. John. Stevens, of this city.’

Not only did this notice give me her dates of birth and death (1734 – Friday, 25th October 1822), it also seemed to indicate that the Mr. Stevens recorded in John Gwynn’s survey on 1772 was my 5 x great-grandfather. Of course there is a 50 year gap between the date of the survey and the date of Lydia’s death, but it seems quite probable nonetheless.

Weft and Warp

In Tim Ingold’s Being Alive, Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description, he writes the following:

“Recall Hägerstrand’s idea that everything there is, launched in the current of time, has a trajectory of becoming. The entwining of these ever-extending trajectories comprises the texture of the world.”

This reminded me of something I wrote some time ago about history and the relationship between history and objects:

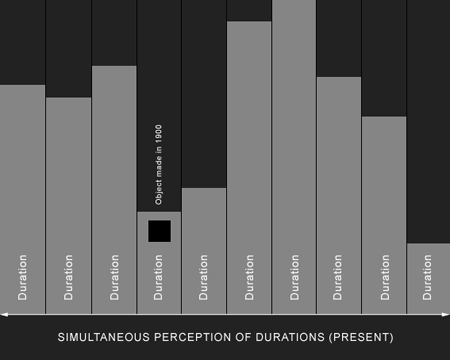

“…what we have is not a series of horizontal strata representing stacked moments in time (days, months, years, centuries etc.), but concurrent vertical lines, or what I have called ‘durations’ where each duration is an object, building or landscape feature and where the present is our simultaneous perception of those that are extant (of course, in the case of buildings, individual objects can also contain many separate durations).

It was Bill Viola who said that ‘we have been living this same moment ever since we were conceived. It is memory, and to some extent sleep, that gives the impression of a life of discrete parts, periods or sections, of certain times or highlights’. Similarly we can say that every object, building or landscape feature has existed in one continuous moment and that it is to some extent the passing generations which gives the impression of the past as being a series of ‘discrete parts, periods or sections…”

This is very similar to what Hägerstrand – via Ingold – describes above and in many ways, the second diagram (above), illustrating the idea of vertical durations, is like a loom, where the durations are the warp threads and our perception of simultaneous durations are the weft, leading to an entwining of what Hägerstrand calls ever-extended trajectories making up the texture of the world.

In this analogy we are both the weft and the warp; both a duration and the perceiver of durations. We find something similar to this, again in Ingold’s writing:

“…since the living body is primordially and irrevocably stitched into the fabric of the world, our perception of the world is no more, and no less, than the world’s perception of itself – in and through us. This is just another way of saying that the inhabited world is sentient.”

Landscape DNA: The Simultaneity of Stories-So-Far

The Past is Time without a ticking clock. A place where paths and roads are measured in years. The Present is a place where the clock ticks but always only for a second. Where, upon those same paths and roads we continue, for that second, with our existence.

In 2006 I visited Auschwitz-Birkenau and since then have visited camps at Bełżec, Majdanek and Natzweiler-Struthof, as well as the battlefields of Ypres, Verdun and more recently, The Somme. All these sites present the visitor with numbers: 1.1 million dead at Auschwitz-Birkenau, 500,000 at Bełżec, 79,000 in Majdanek. At the start of the Battle of the Somme, on 1st July 1916, British and Commonwealth forces sustained 57,000 casualties, with almost 20,000 men killed in action on that day alone. These are all horrific statistics, but numbers rather than people and over the course of the last few years, I’ve looked for ways of identifying with the individuals behind the grim tolls. The tolls are only estimates, and the individuals to whom they allude have become themselves ‘estimates of existence’. Most have left nothing behind; no name, possessions, or photographs. Photographs, where they exist, are often nameless, names on graves are faceless, so how can we know them at all?

One of the most difficult things about my visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau was walking out the gate, performing an action that more than a million people could only ever dream about – if they had the time; most were killed within hours of their arrival. At Bełżec, the memorial to the dead is – in the main – a walk around the perimeter of where the camp once stood. During my visit in 2007, I recorded the walk using a GPS receiver and the fact that I, as an individual, one of several billion people on the planet, could be tracked in this place where half a million people perished, proved particularly resonant. The concept of walking as a means of remembering began to take hold in my work, evolving over time to become a means of empathising – in some small way – with those who’d perished.

In the book Walking, Writing and Performance by Deirdre Heddon, Carl Lavery and Phil Smith, artist Carl Lavery states the following:

“…pedestrian performance is a mode of resistance against the acceleration of the world, a desire, on the part of performance makers, to re-humanise space by encouraging spectators to experience the environment at a properly human pace, the bodily beat of three miles per hour. Implicit in this argument is the belief that walking is conducive to the production of place, a perfect technique for merging landscape, memory and imagination in a dynamic dialogue. Or as Michel de Certeau would have it: ‘The act of walking is to the urban system what the speech act is to language…’.”

In the passage quoted above, I was struck by the idea, as Lavery puts it, of “encouraging spectators to experience the environment at a properly human pace.” Merging landscape, memory and imagination (for which purpose, according to Lavery, walking is the perfect technique) has become central to my work. It’s also something I’ve done quite naturally since I was a child. For me, places have always been a conflation of these things, and as such, quite unique to me.

When I visit historic sites, landscape, memory and imagination merge to create something akin to what others have termed post-memories; ‘memories’ of events of which we can have no real recollection – in particular events that happened before we were even born. How this happens is something which has interested me throughout my research. A kinaesthetic engagement with a place, and our sense of the present are, it seems, both important in this regard.

Finally in the paragraph quoted above, I was struck by the words of Michel de Certeau; the idea that ‘the act of walking is to the urban system what the speech act is to language,’ reminded me very much of what I’ve read before in the work of Christopher Tilley, who in his book The Materiality of Stone – Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology, writes that ‘If writing solidifies or objectifies speech into a material medium, a text which can be read and interpreted, an analogy can be drawn between a pedestrian speech act and its inscription or writing on the ground in the form of the path or track.”

The idea of a path as ‘text’ is something which appeals to me; the notion that as we walk we ‘write’ ourselves in the landscape has a particularly poetic resonance. In his book Lines, a Brief History, Tim Ingold writes that “human beings leave reductive traces in the landscape, through frequent movement along the same route…”. The Old English word writan he tells us, meant to ‘incise runic letters in stone,’ and a correlation can therefore be drawn between the act of walking and writing; a path is something written over years by many different people, incised into the landscape.

Just as when we speak we re-use the same words spoken over centuries – for example fragments of long forgotten conversations – so when we walk, we re-use fragments of other people’s ‘texts’, ‘written’ into the landscape. In this sense, we speak with our bodies words that other bodies have spoken or written before us. As Ingold notes: “retracing the lines of past lives is how we proceed along our own.”

In 2007, the year before she died, my grandmother told me about her childhood in Wales. The following is an extract from that conversation in which she describes her father, Elias Jones, who died in 1929, aged 47, as a result of working in the mines:

‘I can see him now because he went up our garden over the road and the mountain started from there up… and he’d go so far up and he’d turn back and wave to us…’

On visiting Hafodyrynys, the village where my grandmother grew up, I walked up the ‘mountain’ she’d described and followed the path my great grandfather would have taken to work in the mines at Llanhilleth. On top of the hill I turned and looked back down at the garden, imagining my grandmother and her siblings waving back at me from the past. Further on, I stood and looked at the view, rolled out all around me. A hundred years ago I thought, when I did not exist, he would have seen the very same thing. A hundred years later, long after his death, I found myself – through being in that place – identifying with him: I’d found him on the path – one which would in time lead to my being born.

Elias Jones, through frequent movement along that path had written himself into the landscape. A hundred years later, I was – through articulating my own presence through walking – reading part of that text; speaking with my own body his simultaneous presence and absence. In many ways, I was speaking my own presence and absence too.

During that visit, I realised that as well as being a product of the ‘genetic text’ passed down the generations through a myriad number of genealogical lines, we are as much the consequence of pathways walked by every one of our ancestors. DNA is text – a kind of narrative sequence – and the paths which have led to our individual births are a vast text written across the landscape: self and environment, to borrow from Lavery, are umbilically connected.

People are therefore, in a sense, places, and in his book, Lavery quotes Mike Pearson, a performance maker and theorist who states that: “just as landscapes are constructed out of the imbricated actions and experiences of people, so people are constructed in and dispersed through their habituated landscape: each individual, significantly, has a particular set of possibilities in presenting an account of their own landscape: stories.”

Another passage in the book which interested me was that regarding the geographer Doreen Massey. Lavery writes how she offers a ‘conception of space that is interrelational, multiple and always under construction. In her book, For Space, she describes it [space] as ‘the dimension of multiple trajectories, a simultaneity of stories-so-far’.”

I like the idea of space being a ‘simultaneity of stories-so-far’, and it interested me insofar as it rang a bell with some thoughts I’d had previously regarding our own perception of the past. The following is taken from a piece I wrote on the nature of history:

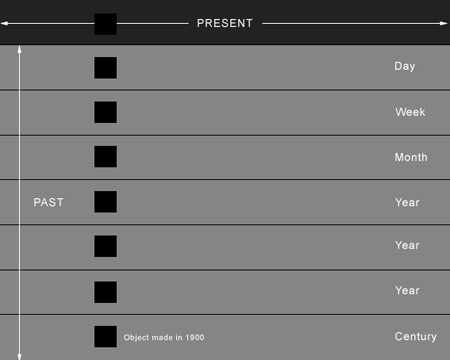

The past is often perceived much like the strata of a rock-face, wherein successive layers of geological time can be seen. We see the past as being built from the ‘ground up’ day upon day, year upon year, century upon century, like bricks in a wall. The problem with this ‘model’ however is that it makes the past difficult to access, the lines dividing each and every moment become like barriers inhibiting our movement between one and the other, particularly where one part is stacked so far below our own in what we perceive as being the present day. Another problem with this way of perceiving the past is that the layers necessarily contain objects, buildings and landscape features which, because of their age, appear in several different layers almost as if they were different things. For example, an object made a 100 years ago, would appear in each of the layers in the diagram below (see Figure 1). It’s rather like someone creating an animation, who draws the same scene a thousand times because it appears in a thousand frames, rather than using the same picture throughout them all.

Figure 1

Whilst thinking about this and while considering the fact that any extant object, building or landscape feature, no matter what its age is always present, I realised that a better model for perceiving the past is one which turns the model above on its side – if not quite its head. Subsequently (see Figure 2), what we have is not a series of horizontal strata representing stacked moments in time (days, months, years, centuries etc.), but concurrent vertical lines, or what I have called ‘durations’ where each duration is an object, building or landscape feature and where the present is our simultaneous perception of those that are extant (of course, in the case of buildings, individual ‘objects’ can also contain many separate durations).

It was Bill Viola who said that ‘we have been living this same moment ever since we were conceived. It is memory, and to some extent sleep, that gives the impression of a life of discrete parts, periods or sections, of certain times or highlights’. Similarly we can say that every object, building or landscape feature has existed in one continuous moment and that it is to some extent the passing generations which gives the impression of the past as being a series of ‘discrete parts, periods or sections, i.e., the perceived layers or strata of our previous – first – model.

Figure 2

These ‘durations’ as I have described them, are indeed ‘stories so far,’ which move, as if they are being told, at the speed of walking – at a ‘properly human pace’ as Lavery puts it.

Returning to the idea of walking as writing, it’s true to say that we don’t always leave a physical trace of our presence when we walk – or at least a visible, physical trace. But, poetically speaking at least, we do leave something behind and this something is often augmented by objects, buildings or landscape features which are contemporaneous with past individuals.

Whenever I visit sites of historic trauma (death camps and the battlefields of World War One), even if they’re empty, I feel as if they’re full; not in a spiritual or pseudo-spiritual sense, but physically, as if they’re full of sculptures. Sculptor Antony Gormley describes his work as ‘confronting existence’ and that, in part, is what we do in places such as Auschwitz; death is, after all, another kind of existence. Walking itself is a means of confronting existence, being as it is a line drawn between absence and presence – just as I’d found in Wales.

“Part of my work,” Gormley writes, is to “give back immanence to both the body and art.” For archaeologist, Colin Renfrew, Gormley is “speaking of the existence of the individual, and the coming into being and self-awareness of the individual as the inhabitant of his or her body.” In reading these quotes, I began to see that the sites of trauma I’d visited, as well as those places relevant to my own family history, were full of what I can only describe as invisible sculptures – sculptures of absence, the physical presence/immanence of all who’ve gone before.

Gormley’s work comprises, in part, casts of his own body which reminds Renfrew of the bodies found in Pompeii; men, women and children frozen at the moment of their death almost 2000 years ago. Buried in ash, the spaces which had once contained their bodies remained after the bodies had decomposed, allowing archaeologists, to use them as moulds by pouring plaster into the cavities.

In light of this, I was reminded of the work of Christopher Tilley, who in his book, ‘The Materiality of Stone, Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology’ writes: “The painter sees the tree and the trees see the painter… in a manner comparable to that in which the mirror ‘sees’ the painter: that is, the trees, like the mirror, let him become visible: they define a point of view on him which renders visible for him something that otherwise would remain invisible – his outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence… The trees and mirror function as Other.”

Just as the trees function as ‘Other’ therefore, so must the sun, the stars, the clouds, hills, mountains, the sea, rivers, the wind, the rain and so on. And in a sense, what Tilley is describing as Other, which ‘renders visible for him… his carnal presence,’ is a sense of being present in the present-day world.

In the book Walking, Writing and Performance, Lavery writes:

“…during… Mourning Walk I was aware of living more in the past than in the present. However at no time did this immersion in memory result in psychic saturation or disintegration. The natural world – the world of trees and stones – was stubbornly present and insisted on maintaining its autonomy and distance.”

When trying to access the past through walking, an awareness of the present – of being present in the world – is vital, and the natural world – the world of trees and stones – does that for us. Understanding the fact that the past was once the present, helps us in some small way to empathise with those lost to the past.

The present moment is a space, one which lasts only for a second – a space comprising the simultaneity of what Doreen Massey calls ‘stories so far’ or what I have called ‘durations’. And it’s in that space that life happens. Behind us and in front, beyond the physical boundaries of that second we are absent. The text is written, or yet to be written – the present being the moment of writing. Gormley’s sculptures then articulate this line between presence and absence, past and present.

In that space, in which we continue with our existence, we hear the birds, we see the sun, feel the wind and rain. In that space, all our hopes are held, all our fears and regrets. Into the space we carry our past in the form of memories. It’s the space of the everyday – one which we often take for granted. But it’s a space we share with everyone who’s ever gone before us.

Again, in his book, Lines. A Brief History, Tim Ingold tell us that:

‘…from late Antiquity right through to the Renaissance writing was valued above all as an instrument of memory. Its purpose was not to close off the past by providing a complete and objective account of what was said and done, but rather to provide the pathways along which the voices of the past could be retrieved and brought back into the immediacy of present experience, allowing readers to engage directly in dialogue with them and to connect what they have to say to the circumstances of their own lives. In short, writing was read not as a record but as a means of recovery.’

This paragraph has something in common with what I described earlier, the idea that just as when we speak we re-use the same words spoken over centuries – fragments of long forgotten conversations – so when we walk, we re-use fragments of other people’s ‘texts’, ‘written’ into the landscape. Walking becomes a means of recovery, where the past can be retrieved and ‘brought back into the immediacy of present experience’. As on the ‘mountain’ in Hafodyrynys, it’s a means of engaging in a dialogue with those who’ve gone before us, and nowhere is this more keenly felt that in places of historic trauma.

It’s as if when walking through these places, we pick up – at random – the threads of other people’s texts. We tie them together, filling in the gaps with our own story. It’s rather like the film Jurassic Park, where dinosaurs are cloned using DNA extracted from mosquitoes frozen in amber. The gaps in the code are filled with modern frog DNA, creating a ‘modern’ dinosaur. Earlier, I stated that people were as much the product of places, and it figures therefore that places are as much the product of people; that the ‘DNA’ of any place comprises narrative lines laid down by everyone who’s ever been there. When we walk, we create new places based on the present day landscape. Our memory and memories, history and of course our imaginations all have a part to play. Within our imagination, we take with fragmentary strands of the landscape’s own ‘DNA’ (or history) and fill the gaps with our own presence and memory. These constantly created spaces (created then destroyed every second) are unique to us, and yet we share them, in that single moment, with all who’ve gone before us, not as part of a crowd, but as one body and mind.

The ‘stubborn’ presentness which Lavery describes is therefore vital to our empathising with the past, and in many ways the most terrifying thing at Auschwitz was the way the trees moved in Birkenau (Auschwitz II), simply because they would have moved that way during the Holocaust.

The writer Georges Perec once wrote that “the desire to find roots, the determination to work from memories or from the memory, is the will above all to stand out against death, against silence.”

I work from memories and the memory and I’m actively engaged in searching for my roots. Is this then a will to stand out ‘against death, against silence?’

Again, in Walking, Writing and Performance, Lavery writes:

“Is not all writing, all art, a response to a loss of some kind, an imaginative way of dealing with lack? …As I use it, the word recovery has nothing to do with re-experiencing the lost object in its original pristine state; rather, it designates a poetic or an enchanted process in which the subject negotiates the past from the standpoint of the present.”

This act of recovery is just the same as that which Ingold describes, where writing (in ancient times) was read not as a record but as a means of recovery. Walking as a means of ‘reading’ or ‘speaking’ the text of other people’s lives is a way of recovering a moment in the past; an ‘enchanted process’ to borrow from Lavery, where we ‘negotiate the past from the standpoint of the present.’

Empathy with the past therefore and in particular with individuals can be achieved, coming via a kinaesthetic response to the present mediated through memory and our embodied imaginations.

Quote from Simon Schama

“…to write history without the play of imagination is to dig in an intellectual graveyard…”

Preface to Citizens

Stories

In his excellent book, ‘The Past is a Foreign Country’, David Lowenthal writes:

“Among the Swahili, the deceased who remain alive in the memory of others are called the ‘living-dead’; they become completely dead only when the last to have known them are gone.”

Having read this, I began to think about Henry Jones, my great-great-grandfather who took his own life in Cefn-y-Crib in 1889. For all intents and purposes, he had, until I (and another distant relative) had begun to research him, been ‘completely dead’ in that anyone with a knowledge of who he was would also have passed away. For many years therefore, he would have existed as a name, inscribed on his grave or recorded in various documents such as census returns. He would have been, apparently, nothing more than that.

Now however, he is part of my family tree, ‘reconnected’ – albeit abstractly – to his own loved ones and those who came both before and after he lived. But a list of names, connected or otherwise is only a part of the story. As Tim Ingold writes, in his book ‘Lines – a Brief History‘:

“The consanguineal line is not a thread or a trace but a connector.”

The line connecting Henry Jones to his forebears and descendants tells us nothing about him. As Ingold explains; ‘Reading the [genealogical] chart, is a matter not of following a storyline but of reconstructing a plot.’ What I want, as far as is possible, is the story, the narrative as it was written at the time.

As I wrote in my essay ‘What is History?‘:

“Human beings [Ingold writes] also leave reductive traces in the landscape, through frequent movement along the same route… The word writing originally referred to incisive trace-making of this kind.’ By walking and leaving our reductive traces on the ground therefore… we could be said to be writing or drawing ourselves upon the landscape – writing or drawing our own history.”

It was only when I visited Hafodyrynys in May 2008 that Henry Jones became – for want of an expression better suited to the 21st century – in the words of the Swahili, ‘living-dead’ again. It was only then, as I walked around the village where Henry Jones lived, walking the same roads and pathways, that I began to read – as far as was possible – a part of his story. I knew the dates of his birth and death (I’ve since learned of his suicide) but these are plot points. Only when retold as part of the story do they start to make an impact, and that story can only be read in the places where he walked.

As I walked, I felt as if I was both recording my own story on the roads and pathways around Cefn-y-Crib, whilst reading that of my ancestors, in particular my paternal grandmother, who lived as a child nearby in Hafodyrynys and who passed away a few months after my visit.

A quote from Christopher Tilley’s ‘The Materiality of Stone, Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology’ illustrates this point:

“The body carries time into the experience of place and landscape. Any moment of lived experience is thus orientated by and toward the past, a fusion of the two. Past and and present fold in upon each other. The past influences the present and the present rearticulates the past.”

As we walked (I visited with my dad and girlfriend, Monika), we would phone her up and tell her where we were, and I couldn’t help but feel that we were walking directly within her memories. Time it seemed had collapsed for a while.

As I wrote as part of an investigation in the Old London Road at Shotover:

“Thinking about it now one can take that analogy and think of it [the road] instead as piece of tape which runs and runs and runs and which every step upon it is like the recording head changing the ground, changing the particles on the tape just a little. And just as we record when we walk so we also play, play the ground which passes beneath our feet. We can hear very distantly the thoughts which came before us.”

So how do we read or hear these ‘stories’, written into the ground and the landscape so many years before we were even born? One clue comes in the following extract from Christopher Tilley’s book, ‘The Materiality of Stones, Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology‘.

“The painter sees the tree and the trees see the painter, not because the trees have eyes, but because the trees affect, move the painter, become part of the painting that would he impossible without their presence. In this sense the trees have agency and are not merely passive objects. Dillon comments: The trees ‘see’ the painter in a manner comparable to that in which the mirror ‘sees’ the painter: that is, the trees, like the mirror, let him become visible: they define a point of view on him which renders visible for him something that otherwise would remain invisible – his outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence… The trees and mirror function as Other.”

If we take the analogy of the mirror for a moment and return again to my essay ‘What is History?‘:

“In a famous definition of the Metaphysical poets (a group of 17th century British poets including John Donne), Georg Lukács, a Hungarian philosopher and literary critic, described their common trait of ‘looking beyond the palpable’ whilst ‘attempting to erase one’s own image from the mirror in front so that it should reflect the not-now and not-here…’

Just as the trees function as ‘Other’ therefore, so must the sun, the stars, the clouds, hills, mountains, the sea, rivers and so on. Where we are in the world, where we stand or walk, which direction we are facing are all significant features in this respect. We are what we are because of where we are at a given moment. We exist in relation to [these ‘Others’] and are at any given moment defined by them….

Last year I visited Hafodyrynys in Wales, the village where my grandmother grew up. Whilst standing on top of the hill where she played as a child and across which her father walked on his way to work in the mines at Llanhilleth, I looked and saw a view I knew he would have seen. I found it strange to think that a hundred years ago he would have stood there, just where I was, at a time when I did not exist. A hundred years on and I was there when he did not exist. And yet we shared something in that view. We had both for a time been defined by it. It was as if the view could still recall him and even though it was new to me, that I was nonetheless familiar.”

We are defined by the world around us and as such we might be said to be remembered by that world. But of course over time the world changes and where things disappear, so do, to some extent, memories. We therefore have to fill in the gaps. I once wrote something about this during a residency at OVADA in Oxford in 2007.

“In the film, the visitors to the Park are shown an animated film, which explains how the Park’s scientists created the dinosaurs. DNA, they explain, is extracted from mosquitoes trapped in amber and where there are gaps in the code sequence, so the gaps are filled with the DNA of frogs; the past is in effect brought back to life with fragments of the past and parts of the modern, living world. This ‘filling in the gaps’ is exactly what I have done throughout my life when trying to imagine the past, particularly the past of the city in which I live.”

I appreciate that my metaphors are beginning to stack up a little. However, where we can fill in the gaps with our own experience is where we can begin to see the past as it was when it was the present.

No Man is an Island

I have written a great deal about how I perceive the past and how I use objects and the landscape to find ways back to times before I was born. In my text ‘What is History‘ I conclude with the following paragraph.

“History, as we have seen, [might be described as] an individual’s progression through life, an interaction between the present and the past. It follows, having seen how the material or psychical existence of things extends much further back than their creation that history spanning a period of time greater than an individual’s lifetime is like a knotted string comprising individual fragments; fragments within which – in the words of Henri Bortoft – the whole is immanent. The whole history of all that’s gone before is imminent in every one of its parts; those parts being the individual.”

I was reminded as I read this paragraph – and in particular the last line – of the poet John Donne and the following words taken from his XVII Meditation:

“No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were: any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.”

Having read this, I thought about some of the work I’ve been making for my forthcoming exhibition in Nottingham, Mine the Mountain. Two pieces are maps of invented landscapes, one of which (the first shown below) is based directly on a map I created as a child, the other based on the outline of Belzec Death Camp as seen in an aerial view of 1944.

The Past is a Foreign Country, 2010

The first map, as I have said, is a contemporary reproduction of one I made as a child. It’s therefore essentially a map of an individual – of me, as I was at the time. It is a place that, although imagined, was real nonetheless, one based on fragments of my memory and my perception of the distant past.

Having been to Wales (in 2008) and imagined all my distant forebears walking the various tracks and roads around the village where my grandmother grew up, I realised how I was very much a part of those places and they in turn were part of who I was. I had existed – at least potentially – in those places long before I was born. All those roads, paths and trackways led in the ‘end’ to me. Of course that sounds a rather egocentric way of perceiving the world and its history, but then I’m not suggesting that I am the only intended outcome. Just as my invented world – my map of me – was made of all those bits of the past I loved to imagine as a child (the untouched forests, the unpolluted rivers and streams) so I can see how this foreshadowed my current thoughts on history; how I am indeed (as we all are) a place, one made of all those places in which my ancestors walked, lived and died.

A quote from a source which is of huge importance to me and my work (Christopher Tilley’s ‘The Materiality of Stone, Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology’.)

“Lived bodies belong to places and help to constitute them so much so that the person can become the place (Gaffin 1996). The body is the medium through which we know place. Places constitute bodies, and vice versa, and bodies and places constitute landscapes. Places gather together persons, memories, structures, histories, myths and symbols.”

Alongside the second map I will be showing a piece of text taken from the diary of Rutka Laskier describing what appears to be an imaginary landscape, though one perhaps based on memories of family holidays to Zakopane, Poland. She was a child when she died in the Holocaust and by putting the two maps together, I want to reflect on the numbers of children who perished, as well as illustrating how within each child – within everyone – the whole of humanity is immanent.

John Donne’s words serve to illustrate this sentiment further still. No man, woman or child is an island. So whilst I have created two maps of individuals, through Donne’s words we can see how these islands comprise pieces of everybody else.

If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less.

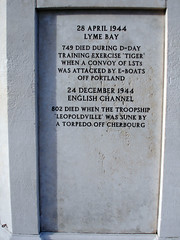

Weymouth

Yesterday I went to Weymouth to look at some deckchairs for use in a number of installations. One such installation I’ve been considering centres around the D-Day landings – I won’t go into the details of what it will entail but I was amazed as I was shown around the front to discover that Weymouth played a pivotal role in the landings themselevs, in that it was from the harbour that many of the men who took part in the invasion left. The coincidence convinced me that this was the place – the only place – where the work could be installed.

On the front is a memorial to the men who took part in the D-Day landings.

Around the base are the following inscriptions.

28 April 1944

Lyme Bay

749 Died during D-Day training exercise ‘Tiger’ when a convoy of LSTs was attacked by E-Boats off Portland.

24 December 1944

English Channel

802 Died when the troopship ‘Leopoldville’ was sunk by a torpedo off Cherbourg.

11th October 2002

Prior to 6th June 1944 the 2nd and 5th Ranger Battalions of the Army of the United States of America depended heavily on men and equipment of the Landing Craft Assault (LCA) Flotillas during training and while developing special assault-techniques on D-Day, these same men of the Royal Navy demonstrated the finest traditions of their service through their courage, steadfastness, and devotion to duty. The successes of their assaults at Pointe du Hoc and the Omaha beaches of Dog Green, Red and White were made possible through their skills and bravery. All World War II Rangers are proud to be associated with the veterans of the LCA Flotillas of the Royal Navy and remain grateful to them, and their vessels both large and small.

We remember your Nation’s sacrifice

60th anniversary

D-Day

June 2004

6 June 1944

Omaha Beach, France

Showing courage and endurance beyond belief 3000 died on D-Day while fighting to secure the beachhead and strategic Pointe du Hoc, spearheading the invasion of Normandy. As this millennium closes we commit this memory to history June 1999.

Further along the beach are more war memorials.

A.I.F.

In memory of Anzac Volunteer Troops who after action at Gallipoli in 1915 passed through hospitals and training camps in Dorset.

As a child, I often went with my family on holiday to the Dorset coast, either to Weymouth or the surrounding areas, and even though my experiences were – it goes without saying – utterly different to those of the men who left Weymouth for France, nevertheless, there is something about these experiences residing in the past as memories which allows me to, in some small way, access the past before I was born. The past (and in particular the distant past) is often imbued with a sense of the exotic – a word which is of course as far removed from the reality endured by the men who fought and died during D-Day as you can get. This ‘exotic’ quality is more akin to the nostalgia we often feel when contemplating our own memories. There is a sensuousness to memories which we experience without recourse to our senses. We see, hear, smell, touch and taste memories internally; we can see them with our eyes closed. Only by being in the place where they happened can we begin to experience them as things which happened in what was then the present. It’s almost as if they are grounded.

Standing in Weymouth and looking out at the cliffs, feeling the wind, hearing the gulls and the waves, I could get a greater sense not only of my own memories, but those of a time when I was not even born. The men left Weymouth and who died on the beaches of Normandy would have known the same feel of the wind, the same sound of the waves – they would have seen the very same cliffs. We can never know what it was like to be in their shoes, but by understanding and observing the present we can at least ground the memories in reality.

Looking at some recent work I’ve done with some of my old holiday snapshots, I can see in light of my visit to Weymouth how they have become more meaningful. The image below is a collage of all the parts of those holiday snaps from which the people have been removed.

The Place That’s Always There (2009).

Echo

Last week I installed a temporary artwork in St. Giles, Oxford entitled Echo. The piece comprised approximately 200 photographs of individuals isolated from group shots of the fair taken in 1908, 1913 and 1914. The date of the exhibition, Wednesday 9th September was important in that it was the day after St. Giles’ Fair was taken down, and the ‘space’ left in its wake (the fair was up for two days and filled the entire street) helped frame the fact that all those people shown in the exhibition, who had once stood in the same street, had, like the fair, gone. I was interested in the boundary between existence and non-existence, the impossiblity – within the human mind – of death as nothing and forever. What I hoped the photographs conveyed was the importance of having been.

The installation required grass in order that I could place the markers in the ground and the War Memorial in St. Giles was the only viable option. What was particularly interesting was how the location altered the meaning of the work in that one couldn’t help identify the people with the memorial and in particular those who fell in World War One. Given that some of the men pictured in the photographs almost certainly went to war and may well have lost their lives, so the work took on a new and poignant dimension. Many of the women would have lost husbands, brothers, fathers, uncles and so on.

Click here to read more about this exhibition.

Old Newspapers

I’ve just spent the afternoon in the library reading through a selection of old newspapers from 1771/2 along with numerous copies from the ninetheenth century. I was hoping, initially, to find anything mentioning a Mr. Stevens, Tailor as in a survey of the city (1772) made by John Gwynn several Stevens are listed. As my ‘several-greats’ Grandfather was born in Oxford in 1811 and was a tailor, I wondered whether one of these might be a relation. Anyway, unsurprisingly I found no such mention, but what I did find were a few tantalising glimpses into the 18th century city.

The first is the theft of some lead on October 11th 1771:

“Whereas a considerable quantity of lead has been stolen from off the gate of the physic gardens’ opening into Rose Lane. This notice is given that whosoever will give information to the Rev.Dr. Wetherell, Vice Chancellor, so that the offender or offenders may be brought to justice, shall upon his or their conviction, receive a reward of five guineas.”

Whether or not the guilt party were ever brought to book I don’t know. A couple of weeks later, another audacious theft occurred, this time in Holywell Street:

“Whereas on Monday the 21st of this instant October 1771, the iron rails to the steps of Mrs. Wise’s house in Holywell were taken away. This is to give notice that if any one will discover the offender or offenders so that they may be brought to justice, shall, on his or their conviction receive half a guinea reward from Francis Kibblewhite in Holywell.”

Looking at my 1772 survey, I see that Mrs. Wise lived at what is now called No.2 Holywell Street. Mr Kibblewhite lived at what is now No.38.

Following a burglary on November 8th 1771 in Old Butcher Row (modern day Queen Street) the reward offered for information was much more tempting – provided of course, one had information with which to complete any deal, and thus be tempted to impart.

“Whereas the dwelling of Mr. John Greenway situate in the Old Butcher Row, in this city was last night broke open and divers sums of money and other valuable effects stolen thereout. Notice is hereby given that if any person or persons will discover the offender or offenders so that he, she or they may thereof be committed, he shall receive the sum of fifty guineas from me.”

This very large amount of money (a guinea was equal to £1 1s) was offered by Francis Greenway. The following week on November 16th, the news appeared again with an addendum:

“N.B. It is discovered that a plain round gold snuff box and eight gold rings, chiefly Mourning ones belonging to the family were at the same time taken away.”

The following week this appears, just below the same story repeated for the third week and addressed ‘To the Publick’:

“Whereas some evil designing persons have maliciously propagated various infamous aspersions which tend to injure our characters relating to the late robbery committed at Mr. John Greenway’s home in old Butcher Row; in order to vindicate and clear ourselves of the said aspersions, we did severally make oath that we were not in any wise directly or indirectly concerned in the said robbery or have any knowledge of the person or persons who committed the same, and we do declare that the said aspersions so far as they tend to lessen or injure our reputations and characters are totally false.”

The letter is signed again by Francis Greenway although whether he is including himself as one of the aggrieved I’m not sure. Below his name are the names of two servants, Mary Staunton and Jane Carpenter who made their oath before the Mayor, John Austin. Francis Greenway offered a further 5 guineas to whosoever gave information leading to the conviction of the slanderers which he increased to 20 guineas later on. This was not the end however. On December 7th 1771 when the same story appeared with the same letter to the publick beneath, Francis Greenway wrote:

“And as it is apprehended more than one person must have been concerned in the above burglary, this further notice is given that any one giving information against his accomplice or accomplices shall be paid the above reward of 50 guineas upon his, her or their conviction and will likewise, upon being admitted evidence, be entitled to a Free Pardon.”

That was still not the end of the matter. On December 21st, he added that the reward of 50 guineas was “besides the forty pounds allowed by parliament for me.”

These notices or stories were printed every week and did not stop being printed until March 21st 1772. Whether anyone was brought to justice I don’t know.

Perhaps the most enigmatic story or notice I read however was that printed on February 8th 1771.

“Whereas a person (supposed to be a Gentleman’s Servant) went out of Oxford, December 12th 1770 over Magdalen Bridge and took the Watlington Road riding a horse with a long tail and leading another with a cut tail on which a Portmanteau was tied: whoever recollects seeing the same person and can give information of his name and place of abode so that he may be spoke withal, shall on such proof receive half a guinea reward from the printer.”

Not exactly 50 guineas, but a very curious notice which has left me, as have the stories above, with so many questions. Who stole the lead and Mrs. Wise’s railings? Who carried out the robbery in Old Butcher Row – was it an inside job? And who was the man on the horse, leaving the city over Magdalen Bridge in the winter of 1770? Time – as far as I’m aware – hasn’t told so far. So, maybe I will.

The Mayos

Having looked again at the gravestone mentioned in the previous blog, I realised that I made a mistake as regards John and Celia Mayo. The date of death, February 18th 1884 refers to the fourth daughter of John and Celia, Alice Amy. What becomes apparent however when looking at the gravestone, is the dreadful toll of deaths suffered by the family. One particularly feels for the father, John Mayo, who having lost his wife at the age of 36, then went on to lose four daughters in the space of 9 years. The youngest was 18, the eldest just 22.

Celia, first daughter, died August 5th 1875, aged 22.

Agnes Lucy, second daughter, died January 16th 1880, aged 22.

Laura Edith, third daughter, died March 28th 1878, aged 18.

Alice Amy, daughter, died February 18th 1884, aged 19.

Ancestry

I’m very pleased to announce that my forthcoming exhibition, Mine the Mountain, will be sponsored by Ancestry.co.uk.

I have been researching my family tree for almost a year now and in that time have used Ancestry to search thousands of records (census returns; births, marriages and deaths etc.) to build what has now become quite an extensive tree with roots stretching back to the mid eighteenth century. And although most of this research has been carried out alone, through using the Ancestry website I have been able to join forces with a relative (a second cousin) who I have never met and who lives on the other side of the Atlantic in Canada. He had already made good progress on one line of my family (that of my maternal grandmother) and through the website, I was able to merge much of that information into my own research (and indeed, share with him my own first hand knowledge of people he’d never met).

Using the website I made very quick progress, discovering hundreds of people, some of whom had been completely forgotten, swallowed up by time and almost lost to the past altogether. And it was in response to this idea of the anonymous mass, that what had started as a hobby became an integral part of my artistic practice.

I have always been interested in history and the past was always going to feature in the work I wanted to make and much of my work over the last two years has stemmed from a visit I made to Auschwitz-Birkenau in October 2006.

As with many historical and indeed contemporary traumas (whether ‘man-made’ or natural disasters), one of the most difficult things to comprehend at Auschwitz (and indeed with the Holocaust as a whole) was not only the sheer brutality and inhumanity of the place, but the scale of the suffering experienced there. How can one possibly comprehend over 1 million victims (6 million in the Holocaust as a whole)? The only way I could even begin to try, was to find the individuals amongst the many dead; that’s not to say I looked for named individuals, but what it meant to be one.

One of the many strategies I used to explore the individual was that of researching my own past; not just that of my childhood, but a past in which I did not yet exist.

Using the Ancestry website I began to uncover names, lots of names which seemed to exist, disembodied in the ether of cyberspace like the names one reads on memorials (such as on the Menin Gate in Ypres), and I was reminded all the while I searched of a quote from Rainer Maria Rilke’s poem ‘The Duino Elegies,’ in which he writes that on dying we

“…leave even our name behind us as a child leaves off playing with a broken toy…”

It is interesting that in looking back on our lives and beyond, we inevitably pass through our own childhood, and indeed, I can remember mine replete with all its toys – a fair few of which were inevitably broken. In Rilke’s phrase above, we have an implied progression from childhood to adulthood and the fate that comes to all of us, but travelling back, we move away from death and think of our childhoods, remembering those toys which in our mind’s eye are always new, or at least, always mended. This sense of moving back and the idea of toys, or things, that are mended again, resonates for me with my research and my using the Ancestry website. One can think of the 800 million names stored in their databases as each being a broken toy, one that when it’s found again is slowly put back together.

Having discovered hundreds of names (or broken toys) in my own family tree, I’ve started to put the pieces back together, looking beyond the names to discover who these people were, and therefore, who I really am. And the more I discover, the more I find myself looking at history in an altogether different way. History is sometimes seen as being nothing but a list of dates, but like the names on Ancestry, there are of course a myriad number of things behind the letters and the numbers (the broken toy in the attic has been to places other than just the attic – and has been things other than just a toy).

Now when I think of an historical date, I relate that to my family tree and consider who was alive at the time. For example, when reading about the Great Exhibition of 1851, I know that at that time Richard Hedges, Ann Jordan, Elijah Noon, Charlotte White, William Lafford, Elizabeth Timbrill, John Stevens, Charles Shackleford, Mary Ann Jones among many others were all alive; what is for me a distant event described in books and early black and white photographs, was for them a lived moment whether or not they visited the exhibition itself.

When this photograph inside the exhibition hall was taken in 1851, they were a part of the moment, even when farming in Norfolk. When the guillotine fell upon Marie Antoinette on October 16th 1791 (I’ve just been reading about the French Revolution), Thomas Sarjeant, Ann Warfare Hope, David Barnes, Mary Burgess and William Deadman were going about their normal lives somewhere across the channel in England, and it’s by understanding their lives – of which I am of course a consequence and therefore a part, that I can begin to understand history as not some set, concrete thing that has happened, but something fluid, made of millions of moments which were at one time happening. Every second in history comprises these millions of moments when the world is seen at once by millions of pairs of eyes.

Therefore, as well as being a huge database of names, Ancestry can be seen as being a database of moments, the more of which we discover for ourselves, the greater our understanding of history becomes. This, in light of the project’s origins at Auschwitz-Birkenau, is particularly pertinent; the Holocaust, as a defined historical event, becomes millions of moments and the Holocaust itself not one single tragedy, but a single tragedy repeated six million times.

In effect, Ancestry allows users to map themselves onto history and the family tree becomes not just a network of relationships between hundreds of people but a kind of physical and geographic biography of the individual. Places we have heard of but never been to, places we have never known before become as much a part of our being as the place in which we were born and in which we live. For example, if there’s a place with which I can most identify physically or geographically, then that place would be Oxford, the town in which I was born, grew up and in which I live. Its streets which I have walked and its buildings which I have seen countless numbers of times, all hold memories – and what are we in the end but these.

Of course there are numerous other places which I have visited and which make me who I am (seaside towns in Dorset where I holidayed as a child for example) but as well as these places are those which, until I began my research, I had either never heard of or never visited: Hafodyrynys, Dorchester, Burton Dassett, Southam, Ampney St. Peter, Minety, Ampney Crucis, Cefn-y-Crib, Kingswood, Usk, Eastleach, Wisbech, Walpole St. Andrew and so on. Furthermore, places I had known and visited were shown to contain memories extending way beyond my own lifetime but of which I am nonetheless a part, or at least, a consequence. I have been to Brighton many times and have many memories of that place, but all the times I have been there, never did I realise how much it and the surrounding area had come to make me who I am.

So, as well as being a vast database of moments, Ancestry can be seen as an equally vast set of blueprints, each for a single individual – not only those who are living, but those who’ve passed away. And just as the dead, through the lives they led, have given life to those of us in the present, so we, living today can give life back to those who have all but been forgotten. Merleau-Ponty, in his ‘Phenomenology of Perception’, wrote:

“I am the absolute source, my existence does not stem from my antecedents, from my physical and social environment; instead it moves out towards them and sustains them.”

Of course our existence does indeed stem from our antecedents (and as we have seen, our physical environment), but what I like about this quote is the idea of our sustaining the existence of our ancestors in return. The natural, linear course of life from birth to death, from one generation to the next, younger generation, is reversed. Generations long since gone depend on us for life, as much as we have depended on them.

In his novel, ‘The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge,’ Rilke wrote the following:

“Is it possible that the whole history of the world has been misunderstood? Is it possible that the past is false, because one has always spoken of its masses just as though one were telling of a coming together of many human beings, instead of speaking of the individual around whom they stood because he was a stranger and was dying?”

This quote brings me back round to what I spoke of earlier; the idea that the past is made up of countless millions of moments – that History is not the concrete thing that has happened, but something more fluid, something which was once happening, and which, given Merleau-Ponty’s assertion above, is still happening, or at least being sustained. These moments are the world as seen by individuals. In Rilke’s quote, the history of the world, represented by the masses, has its back turned against us. We cannot see its face or faces, only the clothes that it wears. But the stranger in the middle, around whom history crowds is looking out towards us, and if we meet their gaze, we make a connection, we see the individual. And for a moment they might be a stranger, but through the dialogue which inevitably begins, we get to know them and the world to which they, and indeed, we, belong.

As I’ve said, Ancestry is more than a network of discovered (and undiscovered) relationships between hundreds of people; it’s also an immense collection of dialogues; one can imagine the lines which connect individuals as being like telephone wires carrying conversations between the past and the present. And the more one thinks of all these nodes and connections, the more one begins to see that Ancestry is also a metaphor for memory – after all, what are memories but maps in the brain, patterns of connections between millions of neurons which make a picture of what once was: history as it really is.

Mine the Mountain will run between 1st and 8th October 2008 in Oxford. Download a PDF for venues.

The Gate – A Reflection

Today I made what one might term an ‘intervention’ in the Larkin Room of St. John’s College as part of the Travel and Trauma Colloquium which is being held there today and tomorrow. The work has been written across two large glass doors and throughout the day I’ve been reflecting on its meaning in light of answers I have given to questions posed by delegates and also in light of the papers delivered as part of the colloquium.

When I started to create the work in the morning, the weather was beautiful; blue sky, sun – a perfect Spring morning. Yet very quickly the day changed and as I was writing about the bad weather on 26th March (that being the day on which I wrote the text: see Work in Progress – The Gate) so the heavens opened and the rain (and hail) began to fall. And at once I began to think about the weather and history (as you do). History (with a capital ‘H’) is of course full of accounts of bad weather (storms, droughts and so on) but what one doesn’t read (for perfectly understandable reasons) is accounts of average or day-to-day weather conditions in relation to less than average events. There are of course numerous historical exceptions to this, such as in the diaries of Samuel Pepys whose accounts of the weather serve to bring the seventeenth century alive, but as the rain fell, just as it had over two weeks ago, I began to wonder what the weather was like at times of less than average – great – historical events. In my text I wrote:

“It’s stopped. The rain, but all around, the colours are by a few degrees darker.”

And I wondered, how were colours similarly changed in the past?

I was talking with a delegate about how it is such small things which tell us the most about the past, and knowing how the weather was on certain notable days in history would help paint a better picture of the past. There isn’t much weather in history, some yes, but there should be more! Anyway I digress… suffice to say, what the similarity in the weather showed me, was how from year to year, century to century, rain is always rain, sun is always sun. They both come and go along with fog and snow. They help fill in the outlines of facts with colour (the outlines in my case were the words I was writing).

Going back a moment, to Wednesday when I typed up the transcript (the text of what I had written on 26th March) I found the version I was typing was almost a dreamlike replica of the actual event. It was very different to remembering the event, for the remembered event doesn’t follow the same temporal pattern as the memory inspired by the typed text. The memory (not that inspired by the text) of that time is limited to a few images which blur and blend together to create an homogenous view of the hour I spent in the Larkin Room; on remembering it, I have by no means the sense of any linear time. Writing it out word for word however was like re-living that moment, but time was changed to the time it took me to type it up again; the hour became more like two – but it was linear all the same.

After a few of the speakers had delivered their papers I began to consider what I could see as a connection between tourism and history. One of the questions raised in the colloquium was why we are tourists? (The question emerged from a discussion about 19th century tourists but it still holds today) What are we doing when we visit other places? One of the answers which emerged was that we are somehow comparing the places we are visiting with that from which we’re from, usually unfavourably. We go away in order to return grateful for what we have, we travel, in part, to confirm that where we live is better. Of course this by no means universal – far from it, but travel often augments are sense of home.

As I wrote in my introduction to the project, for me, it’s the individual tourist’s resolution of a disquiet resulting from a shift in the status of a place – the act of leaving or being able to leave – which in some respects makes such places popular today (heightening as they do our sense of existence, of life).” Just as we return from our holidays with a heightened sense of home, so we return from the camps with a heightened sense of life.

We are I believe, in History, tourists of the past. History is a place, a foreign country which we can visit and leave. It goes without saying that those in the past cannot. When we write or read about the past, we are making our own barbed-wire fence to keep the past in. We look as Wiesel says but go no further. We observe but cannot participate, we see from a distance. The barbed wire keeps us out just as it keeps the past in. But as I have written lately in regard to another project (Umbilical Light), to read history, to know it properly – to understand it – necessitates our own non-existence, we have to tear down the wire and enter the past into which we must then dissolve like smoke in a grey sky. The text of history books is therefore an armature by which we are shaped, it makes us the living and those behind the dead. But what about the not-yet-born? Are they also to be found behind the text, or like the dead within the words itself? As I have already written, “to know it properly necessitates our own non-existence” and in our conscious minds that becomes the very image of death. Does that not mean therefore that we exist amongst them?

As one can see, the creation of this work today in the context of the colloquium has thrown up many more questions. But to summarise… the historical text in respect to trauma acts as a fence to keep that trauma at bay, we can read of the trauma in words and glimpse a world behind them, but as when one reads the words on the window, we cannot see the world very clearly. If we focus on the world behind, we lose sight of the text, of the past. Standing in Auschwitz-Birkenau I could of course see the world as it is now, but the words I had read seemed vague, I could not correlate the two – my mind simply couldn’t conceive it. And now, when I return to the words, my memory of the place in which I’d stood is vague, as vague perhaps as the images I have of the past and all its traumatic events. I have gone to the gate but no further.

Oxford’s Lost Streets

Appropriately for the work I’ve been doing on Oxford Destroyed (itself, part of my Tour Stories project), I chanced again upon a map of the lost streets of Oxford. I first found it a year or so ago, and it was only in conversation today that I remembered it; strange how things acquire relevance at a much later date. The map shows a number of streets and lanes lost to the city by the 17th century; among them Exeter Lane, Schools Street, Frideswide Lane and Jury Lane (the rather unfortunate Shitbarn Lane was also amongst their number). Looking at the map, I couldn’t help think of the ‘map’ I’ve recently ‘made’ as part of the the Oxford Destroyed project; the aerial view of the fictional ruined city.

Thinking about the ruined cityscape, I imagined as I ‘walked the ruins’, how the layout of the streets would perhaps change as new routes were cut through the rubble of buildings, and, looking at the map of the lost streets of Oxford along with those which are still in existence, one can see how these changes are in fact all part of the natural evolution of the city.

In my introdction to Tour Stories I wrote:

As old as it is, Oxford is like every city, one which constantly changes. People come and go, passing through its streets as daytrippers; others live a lifetime here and never leave. Generations come and go, stones corrode; whole buildings are lost to progress. Every day the city is in some small way renewed, restored, destroyed and rebuilt. And with every building that is lost, with the death of every one who has ever known it, so the city changes.

The one thing that has changed little over the centuries is the layout of the streets. Buildings as I said above are lost to progress; generations come and go. One of the things that defines Oxford as being what it is is this ancient layout of streets and lanes down which people have walked for hundreds of years. But nevertheless as the map has shown, even these streets can be removed. High Street, Queen Street, St. Aldates and Cornmarket Street might well have stayed more or less intact (albeit the last three with different names) but those such as I listed above have succumbed.

The idea of streets lost to time beneath various buildings is to me as enigmantic as the lost names of John Gwynn’s survey (1772), a document I have been using on another project; 6 Yards 0 Feet 6 Inches and just as I am exploring this survey through a piece of sonic art/composition, so I want to explore these missing thoroughfares. The spaces still exist of course; Jury Lane has been swallowed up by Christ Church, Exeter Lane by the Bodleian Library, Schools Street by Radcliffe Square (part of it is still extant and is now known as St. Mary’s passage) and Frideswide Lane also by Christ Church.

The lost streets also interest me in relation to other projects; for example, the route between the two sites for my Mine the Mountain exhibition in Autumn (the Town Hall Gallery and the Botanic Gardens) are connected by Deadman’s Walk, the route taken along the old city wall by Jewish mourners in the 13th century. It seems to me that some of that route was along what its shown on the map as being Frideswide Lane, but what interests me in particular is Jury Lane off what is now St. Aldates. In the Victoria County History for Oxfordshire, it states :

Jury Lane (c. 1215-25): Little Jewry (1325); Jury Lane (1376); Civil School Lane (1526). Closed c. 1545 and incorporated in Christ Church.

Little Jewry corresponds with Great Jewry, the old name for St. Aldates which was, after Great Jewry, known as Fish Street. It was the mediaeval Jewish Quarter and the missing street strikes a chord with the theme I have been exploring for the past eighteen months or so; the missing of the Holocaust.

This theme of missing people has lately found form in another project – Umbilical Light and seeing the faces in this work, it is interesting to see how all these works are becoming intertwined.