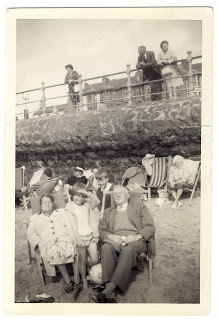

Recently purchased photographs.

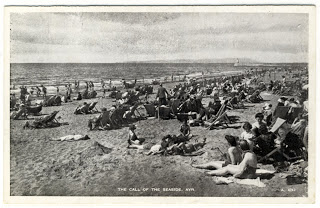

Deckchairs 3

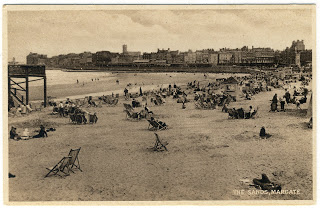

Deckchairs 2

An Act of Imagination

There’s a shop in Paris where I like to go, whenever I am there. In a box you can rummage through a small pile of photographs, miscellaneous images, nothing overly special, but for a few Euros one of them can be yours. That shown below is the last one I bought.

The photograph is small; two and a half by three and a quarter inches. It’s damaged and indistinct; blurred in parts, but nonetheless one can see the interior of a church, within which a small group of women and girls stand facing towards the altar. The photograph was taken from above, perhaps from a gallery opposite the pulpit which one can see on the opposite wall. The pulpit’s draped in material, whether that’s normal or for a special occasion I cannot say. I cannot tell what is going in, but clearly something’s happening beyond the frame of the picture (the world is happening beyond the frame of the picture – as are we, the viewer). As for a date; given the hats, I would say it was taken sometime in the 1920s.

The photograph is fragile. It has the feel of an Autumn leaf, dried and picked from the ground the following Spring. When I hold it in both my hands, my thumbs discover very slight depressions where others have looked before me. The way the paper’s warped, the way that it bends, tells me it’s been looked at many times.

Where the picture contains the trace of someone who was loved, the paper carries the gesture of the lover.

Of course we cannot know this, not for certain. But history is an act of imagination.

Who is the object of his or her attention? My eyes move to the girl at the front, dressed in white or pale colours and wearing a matching hat. My left thumb, in its slight depression almost seems to touch her, mimicking the gesture of the one to whom it belonged. There’s something secret about the image, as if whoever took it shouldn’t have been there, shouldn’t have possessed her. It’s an image that’s meant to be kissed, secreted away in a wallet. Affection has caused the wear in the corner.

She knows she’s being photographed. She knows that someone loves her. She can see in her mind’s eye the gallery behind. She can sense the gaze of her admirer. But then the paper tells me she didn’t turn around, she never returned the gaze. Ever.

Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century

On the first day of this month, I travelled to Paris on Eurostar and met my girlfriend Monika at the Gare de Nord station, she having travelled in from Luxembourg by TGV to Gare de l’Est. I was last in Paris in 1992/93 (the exact date eludes me) on a visit made as part of my degree in Art History, and although my memories of the city were rather vague and (before re-visiting) few, my impression of it was nonetheless intact and fairly lucid. From the pretend statue at Sacre Coeur (a woman, painted white, standing still), to being lost somewhere near Les Halles, from the pastels of Odilon Redon in the Musee D’Orsay, to Rodin’s ‘Balzac’, from the Musee Moreau to a few trips made on the Metro, I could adduce that Paris was beautiful, and, as Walter Benjamin described it in his Arcades Project, the ‘Capital of the Nineteenth Century.’

This sense of it being a nineteenth century city might owe as much to the fact that much of it was indeed built (or rebuilt) in that period (with the extensive renovations by Haussmann in the 1860s) and that its ‘symbol’ the Eiffel Tower, was constructed between 1887-89 as the entrance arch for the Exposition Universelle (the novelist Guy de Maupassant, who claimed to hate the tower, supposedly ate lunch at the tower’s restaurant every day. When asked why, he answered that it was the one place in Paris where you couldn’t see it).

The city’s character is formed as much by an abundance of 19th century literature (Zola, Baudelaire, Balzac, Huysmans…) and art (Realism, Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Symbolism…) than simply ‘bricks and mortar’, yet, despite this sense, it’s by no means a city stuck in the past at all, rather it’s very much of the present, as if the intervening time had not intervened, as if there was nothing to intervene between.

November the 1st is All Saints Day, and by tradition, people in many European countries, including France, take flowers to the graves of dead relatives. Our hotel room, overlooked the cemetery at Montmartre which, having unpacked, we visited.

For Monika, being Polish, the day was very much part of her own tradition, and one of the first things we saw as we walked around, was a group of Poles reciting a prayer for a fellow countryman laid to rest in the cemetery. The cemetery itself was interesting inasmuch as it was very much a part of the city, rather than a place divorced from life – a sense augmented by the bridge which ran above it, beneath which the tombs of the dead resembled makeshift dwellings erected by the homeless; constructions for the purpose of temporary habitation, rather than eternal rest. Indeed, given the occasional broken pane of glass we wondered whether or not they were in fact used as shelters; where the living tap the dead for respite from life.

These little dwellings were beautiful, especially where time, which ought to have let the dead alone, had scratched away at the doors, much like the vagrants seeking shelter from the rain.

The first grave we saw took my interest, since a cat was laying on top of it, dead centre, looking towards the headstone. I took a photograph (which I have since, accidentally deleted) and immediately, a lady, standing with a man (I presume was her husband) asked me in French, ‘why did you take a picture?’ I must confess here that I do not speak French and relied on Monika who does. I explained that I was interested in the cat and was amazed then to discover that the grave was that of her mother. Suddenly, from an anonymous grave with an anonymous name, the memorial had come to mean much more. There was a physical, living connection. She explained in polite conversation, that the cat had been there most of the day and hadn’t moved even when she busied herself about the grave arranging flowers and so on. Cats, we were to discover, were a common feature of the cemetery.

One sculpted tomb was especially beautiful. It showed what I presume to be the deceased, not as he was whilst living, but as he was dead. His sunken features, his closed eyes, and the exposed shoulder all pointed to something deeper than sleep. The eyes in particular were striking, in that one could see they were the eyes of a man who would never open them again. The shroud had been pulled back, to allow one last look at his face, a look which had lasted over a century. I say, as he was dead, but of course he still is dead, and this sculpture serves in a way to remind us, that even in death we are not free from ‘time’s relentless melt’.

On our second day in Paris, we visited the Louvre which, I remembered, I hadn’t visited during my first stay in the city. The building is indeed impressive, as are the queues which inevitably form outside. Nevertheless, having joined the queue outside we soon found our way to the queue inside which as well as being much longer was even slower to move. In fact, it took almost an hour to get a ticket which wasn’t surprising considering that one of the two tills serving our queue was closed and when that which was closed finally opened, the open one, for the purposes of consistency, closed, and this fat caterpillar of people continued chewing on its incredulity.

Once in, I found the Louvre to be almost worth the wait, although the queue had sapped our strength somewhat, and what one needs when walking around the palace is all the strength one can muster; mental as well as physical. What did strike me was the bizarre behaviour of most of the other visitors, something which I remembered as having struck me when I visited what I think was the Grand Palais during my first visit. Back then, a number of people walked around the galleries videoing continuously, looking at everything through the eyepiece of a video-camera, and now, in this increasingly digital age, the same is true but on a much larger scale. Maybe it is something to do with our contemporary culture which means we cannot see something unless it’s reproduced, we cannot know it except through facsimile, that things are not received as being experienced unless captured by a camera. Imagine, you’re approaching a painting, a genuine da Vinci (not the Mona Lisa in this instance). You are about to see something which you know the great man saw himself, something with a provenance dating back over five centuries, an image which countless numbers have looked at since its creation. What do you do? Well, the woman in front of us framed it in her camera, took its picture and walked off looking at the image on her camera’s display. The difference between something original and a copy (and by copy I mean a skewed, 5 megapixel digital photograph) has, it seems, been attenuated to such an extent that there’s no longer any perceived difference at all.

Near to where this ‘incident’ took place is the room which houses the Mona Lisa, a painting whose popularity is, in part, due to the viral-like profusion of its myriad reproductions. On posters, postcards, badges, T-shirts, calendars, mugs and so on, the image is better known than any other in the world, and so, as if she were a celebrity, people crowd about her – as she gazes out from behind her bullet-proof screen – all wanting a copy of their own. Phones are raised amidst the clamorous throng like numerous periscopes; cameras snap at her heels. It really beggars belief.

There were no throngs of people slobbering around Holbein’s portrait of Erasmus, or Vermeer’s Astronomer, and there was no-one standing in front of Ingres sublime portrait of Louis Francois Bertin, a painting which at 116 x 95cm, is, if not in scale, truly epic. Bertin looks out from across almost two hundred years, as alive as he was then. He looks at you as you dare to return his dismissive gaze. One can almost hear him scoff. You are mortal. You can almost hear him say it. He is immortal and you know that he is thinking it. He looks right through you at the centuries to come when you will be long gone from his gaze. “I will still be here,” he says. It really is one of the great portraits.

An artist well known for his monumental works, Anselm Kiefer, was at the time of our visit exhibiting three new works commissioned by the Louvre. It took us a while to find them, and when we did I must say I was rather disappointed. Whereas Ingres more modest-sized portrait was made vast in the palace, Kiefer’s painting ‘Athanor’ despite its scale was rendered rather small. The two sculptures either side were somewhat peripheral and reminded me of Christmas trees which after New Year start to outstay their welcome. This is not to say that any of these works are bad, they’re not – far from it. But somehow in this setting they just didn’t seem to work.

After the Louvre, we were given a guided tour by one of Monika’s friends of the Marais district, which was a real treat. The Marais district (meaning marsh or swamp), spreads across the 3rd and 4th arrondissements on the Rive Droit, or Right Bank of the Seine. According to one of the many websites on The Marais, it was:

“… in fact a swamp until the 13th century; when it was converted for agricultural use. In the early 1600s, Henry IV built the Place des Vosges, turning the area into the Paris’s most fashionable residential district and attracting wealthy aristocrats who erected luxurious but discreet hotels particuliers (private mansions). When the aristocracy moved to Versailles and Faubourg Saint Germain during the late 17th and 18th centuries, the Marais and its mansions passed into the hands of ordinary Parisians. Today, the Marais is one of the few neighborhoods of Paris that still has almost all of its pre-Revolutionary architecture. In recent years the area has become trendy, but it’s still home to a long-established Jewish community.”

Evidence of the Jewish community, and, in particular, the traumas suffered at the hands of the Nazis and the Vichy government can be found in the Holocaust Memorial, as well as the memorial in the Alle des Justes, dedicated to all those who helped the Jews in such dangerous and terrible times; thousands of anonymous names (unknown at least to visitors) who nevertheless did so much, to do good in a very bleak world.

On numerous walls of various buildings were plaques dedicated to the hundreds of children deported from the district’s schools. Having visited some of the terrible places where some of these children ended up, it’s somehow even more distressing to see the place from where they were taken.

Evidence of the area’s mediaeval past can be seen in its surviving ancient wall, the only section left of the Philippe Auguste fortifications which date back to the 11th and 12th centuries. It’s just one of the many features which distinguishes this part of Paris from the rest of Benjamin’s ‘Capital of the Nineteenth Century’.

But it’s more than just the old buildings, the place has a character which is quite unique; it’s quite understated (although not entirely); most unlike the sweeping brovado of Haussmann’s boulevards. In one part of Marais, there is a group of antique shops, called Village St. Paul, where we came across a photographic shop selling old photographs. This shop, called ‘Des Photographies’ was a place in which I could have spent several hours sifting through snapshots of times long gone, and although we were pushed for time, we did purchase two photographs, or rather one and a half, for one of the photos had been cut from a bigger picture.

The first shows a young woman, standing in the rain. I cannot tell exactly when it was taken, but I would imagine it’s some time in the 1920s or 30s.

I liked this for the fact it had been cut from a bigger photograph. But why was it cut? Was it malicious? Was it through heartbreak? Was someone cutting this woman, this memory, from their life? Of course it could have been anything but malicious.

The second photograph, which Monika bought for me, is a group portrait, perhaps a family, taken around the end of the nineteenth century.

This photograph is interesting for many reasons, one being that no-one is looking in the same direction. Only one person, the woman standing behind the old lady (seated) is looking at the camera. The photograph itself, judging from the back, had at one point been part of an album, and one can’t help wonder when looking at it what other pictures accompanied it within that collection. Individual portraits of those within the picture perhaps? Images of where they came from? Who were these people, these men and women who have since lost their names? It’s strange, but sometimes names outlive the body (on plaques and tombstones) or bodies (or at least their alchemical equivalents) outlive the names (such as with these photographs), but rarely do the two continue to coexist.

The following morning we made our way to the largest and most famous cemetery in the city, Pere Lachaise. The cemetery takes its name from Pere François de la Chaise (1624-1709), confessor to Louis XIV, and is reputed to be the world’s most visited cemetery, not that it seemed particularly busy as we walked around. Armed with a map upon which we’d marked the graves we wanted to see, we spent a few hours wandering through the streets and avenues of this vast necropolis.

Among the graves we visisted were those of, Apollinaire, Balzac, Sarah Bernhardt, Bizet, Gustave Caillebote, Chopin, Corot, Daumier, David, Delacroix, Paul Eluard, Gericault, Ingres, Moliere, Piaf, Pissarro, Proust, Seurat, Gertrude Stein and Oscar Wilde.

Theodore Gericault (1791-1824)

Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot (1796-1875)

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780-1867)

And there was something quite strange about seeing the graves of painters whose works we had seen in the Louvre the previous day, artists such as Ingres, who’d given Louis Francois Bertin immortality through his portrait. It was hard to reconcile the fact the he – Ingres – had been dead and buried in this place for 140 years, over a hundred years before I was even born, whilst fresh in my memory was an image which would have once occupied a space in his own: the intervening time had not, as I said earlier, intervened at all.

As with the cemetery at Montmartre, what I found myself drawn to were the graves of those who’ve not left behind a tangible heritage (paintings, discoveries, books etc.). Those names without bodies; scratched like grafitti, by a vagrant time who wanders amongst the stacked sepulchres. Names which do not ring bells when you read them, into whose shapes the moss has grown; names around which death has become less eternal; fragile like glass, broken in the bent and buckled leading of once replete windows.

In broken windows such as these, we see the passing, not just of a life, but of memories; the passing of those who came after the deceased with whom the increasingly vague memories of a distant relative melt into further graves. In every cemetery, you will find hundreds, maybe thousands of anonymous names; names and numbers from which we are separated by generations, decades or even centuries, and of course the ultimate experience: death. And in a cemetery, perhaps somewhere in France, are the names of those people in the photographs I bought in Le Marais; the single woman cut from the bigger picture (in more ways than one), the old lady seated on a chair in the sunlit garden, the two women beside her, and the three men all looking in different directions.

Having said goodbye to Monika at Gare de l’Est, I listened to ‘In Our Time’, a podcast from the BBC. The episode I was listening to was on the 17th century philosopher Spinoza, whose work George Eliot had translated in the 19th century, and whilst discussing Eliot’s epic novel Middlemarch, one of the speakers paraphrased an extract from its conclusion, an extract which I have since discovered, just as she had written it:

“But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.”

What we leave behind (our legacy) is not justified solely by its apparent value or greatness; whether or not it’s great art or literature, or a discovery which will prove a catalyst for even greater advances. It is not dependent on whether or not we have made some kind of sacrifice or acted with courage in times of great affliction. It is also those unhistoric acts of which Eliot speaks, by people who in many cases are not even names anymore. It’s often the decidely average which plays the greater part. Everything, even the mundane has an influence on the world.

In the translator’s forward to Walter Benjamin’s even more epic Arcades Project, Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin write of Bejmain’s intentions as being:

“to grasp such diverse material under the general category of Urgeschichte, signifying the ‘primal history’ of the nineteenth century. This was something that could be realized only indirectly, through ‘cunning’: it was not the great men and celebrated events of traditional historiography but rather the ‘refuse’ and ‘detritus’ of history, the half concealed, variegated traces of the daily life of ‘the collective,’ that was to be the object of study, and with the aid of methods more akin – above all, in their dependence of chance – to the methods of the nineteenth-century collector of antiquities and curiosities, or indeed to the methods of the nineteenth-century ragpicker, than to those of the modern historian.”

Paris is indeed the capital of the nineteenth century, but what of the nineteenth century itself? As the French philosopher Henri Bergson wrote, who is himself commemorated in the Pantheon:

“There will no longer be any more reason to say that the past effaces itself as soon as it’s perceived, than there is to suppose that individual objects cease to exist when we cease to perceive them.”

Somewhere, the century still exists and Paris is still its capital.