Yesterday, at the London Art Fair, I found – amongst a plethora of ‘not very good’ and downright terrible art, an artist whose work – although disturbing -truly impressed me. It’s not the sort of work you’d want on your wall perhaps, or which would likely be snapped up by the likes of those idiots who it seemed were happy to shell out 5 grand for a print of one of Damien Hirst’s assistant’s facile spot paintings (albeit one signed by the Overlord of artistic tat), but its power was striking.

For a number of years I’ve looked to create work which facilitates an empathetic engagement with anonymous individual victims of past atrocities. This work has variously found its form in paintings, sculpture and mixed media pieces using documentary and archival material such as photographs. Where these photographs have been black and white, I’ve looked to see how colour might be used to foster that empathetic reaction.

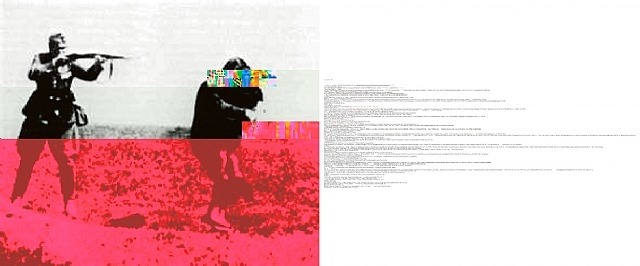

David Birkin’s work, ‘Untitled I’ does everything that I have tried to do. It’s a brilliantly conceived work and one which is conceptually perfect. The work, disturbing as it is can be seen below.

The image shows a woman about to be shot by a German soldier. The woman, like so many of the Nazi’s victims is anonymous, one more human being to make up the grim toll of 6 million killed in the Holocaust. But where so many names have been forgotten, many of course remain, trapped – like flies in amber – in the meticulous records kept by those who carried out these unimaginable crimes.

The black and white photograph printed on the left of the image has been distorted with fragments of colour, and on the right of the image we find the computer code for the original digital image, into which Birkin has placed the name of one of the countless victims. This ‘anomaly’ in the code is revealed when the image – with the anomalous name – is reprinted. The distortion is the name as read by the computer.

It is a brilliant concept. The computer code, without the name, is to (most) human eyes, little more that an incomprehensible mass of letters and numbers. It’s the equivalent of the vast and grim statistic offered to us by history. Its equivalent image is black and white – a far cry from the reality of a world full of colour – the world we know and which every one of the six million victims knew. And yet when a name – an individual – is inserted, the image is changed (distorted) with a pattern of colours, reminding us that the world of the Holocaust was not black and white, but one full of colour, of summer days and everything which we take for granted today.

The average man, woman and child are not the types of people who normally make up history, unless they are heaped together as victims, masses and mobs. They are often anomalous where history is concerned, but nonetheless vital and full of colour, something which Birkin’s work brilliantly portrays.