Some of my work will be shown at the Sidney Cooper Gallery, Canterbury until 17th December as part of an exhibition entitled: ‘Remembering, We Forget; Poets, Artists and the First World War.’

Chinese Landscape Painting

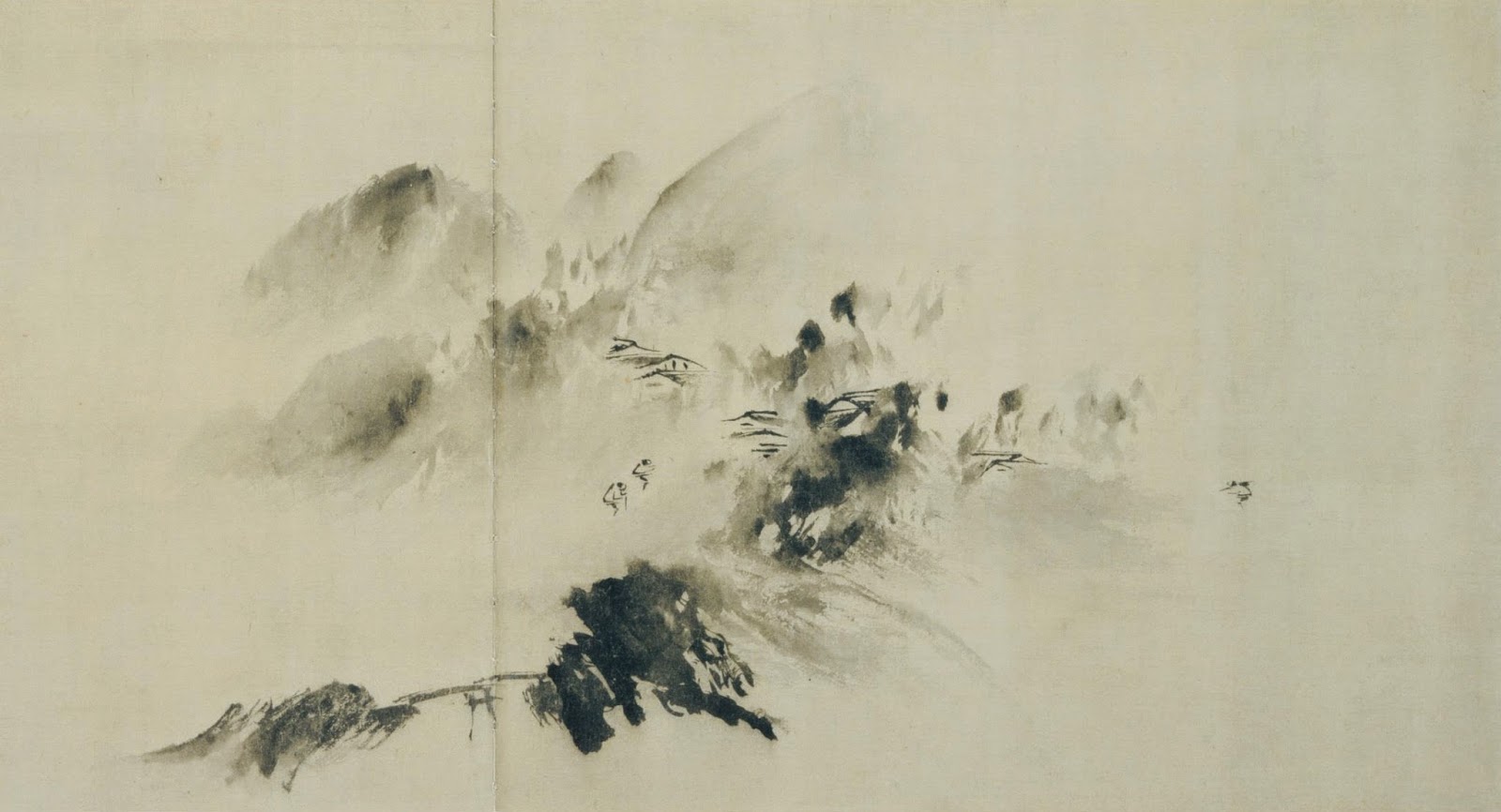

I’ve never before considered myself a fan of Chinese art but there have been times (most recently in the British Museum) when I’ve been overawed by a particular work. I refer in particular to early (11th-14th century) landscapes which move the viewer in a way one doesn’t find in the Western landscape tradition until much later on. (Why did it take so long for landscape painting to develop in the West? And why was it such a key part of painting in the Far-East so early on?) Paintings such as that below (Mountain Village in Clearing Mist by Yu Jian – made all the more extraordinary when one considers it was painted around 800 years ago in the mid 13th century), transport the viewer to a time long gone; they reveal – much as with the 17th century Japanese haiku of Basho – a moment long since past; not so much through what they depict but how it is depicted.

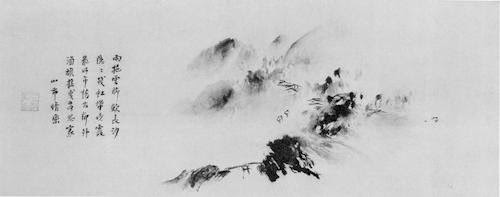

If I’ve never been a fan of Chinese painting per se, I have always admired Chinese calligraphy, which is of course, in itself, a form of painting. One can see in the full view of Yu Jian’s painting below, the text on the left hand side.

One can see here how the landscape itself becomes a kind of text, arranged not in straight lines, but in accordance with the serpentine lines of mountain paths, the drifting patterns of mist and the directions of distant sounds carried on the wind.

With works like these, it’s almost as if you see the landscape before the painter himself. We first see the work as a whole (the landscape as a whole), but then, whilst picking through the gestures of the artist, evident enough in the brushstrokes, we see the landscape as it is – or was – revealed. Yu Jian’s painting is not a painting of what was experienced, but rather the experiencing of what was experienced.

There’s a quote I’ve often used from Christopher Tilley. In his book, The Materiality of Stone – Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology, he writes:

“The painter sees the trees and the trees see the painter, not because the trees have eyes, but because the trees affect, move the painter, become part of the painting that would be impossible without their presence. In this sense the trees have agency and are not merely passive objects… The trees ‘see’ the painter in a manner comparable to how a mirror ‘sees’ the painter: that is, the trees like the mirror, let him become visible: they define a point of view on him which renders for him something that would otherwise remain invisible – his outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence… the trees and mirror function as other.”

Like the trees, the mountains share that agency; they too ‘see’ the painter’ and it’s almost as if the painting becomes a painting, not of Yu Jian looking at the mountains, but of the mountain ‘seeing’ Yu Jian. It’s not the mountain that is made visible on the paper, but the artist’s outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence.

Latest Exhibition

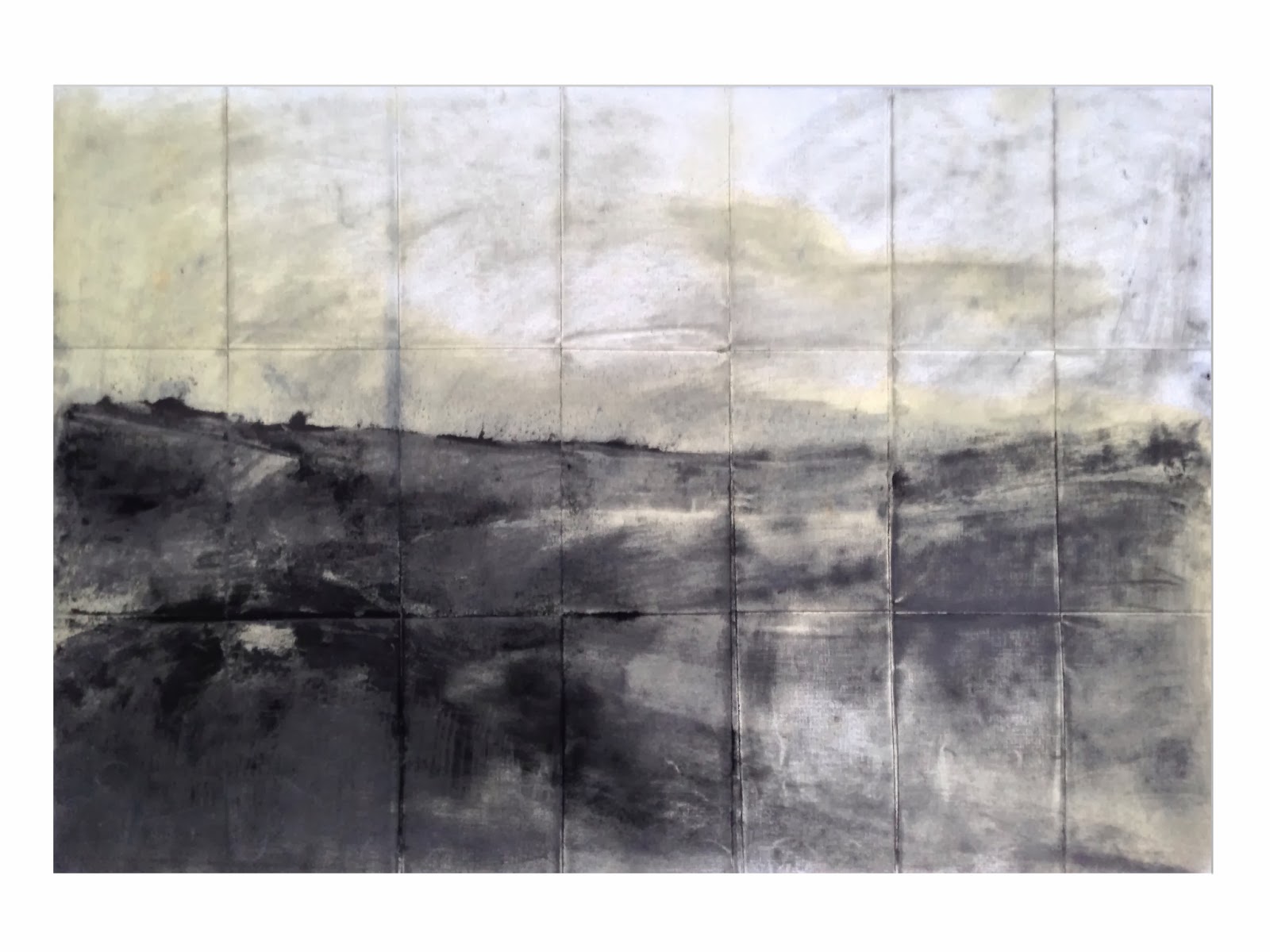

I will be exhibiting with my wife, Addy Gardner, in Plymouth from 4th-26th April 2014. Some of the work I’ll be showing can be seen below.

War and The Pastoral Landscape

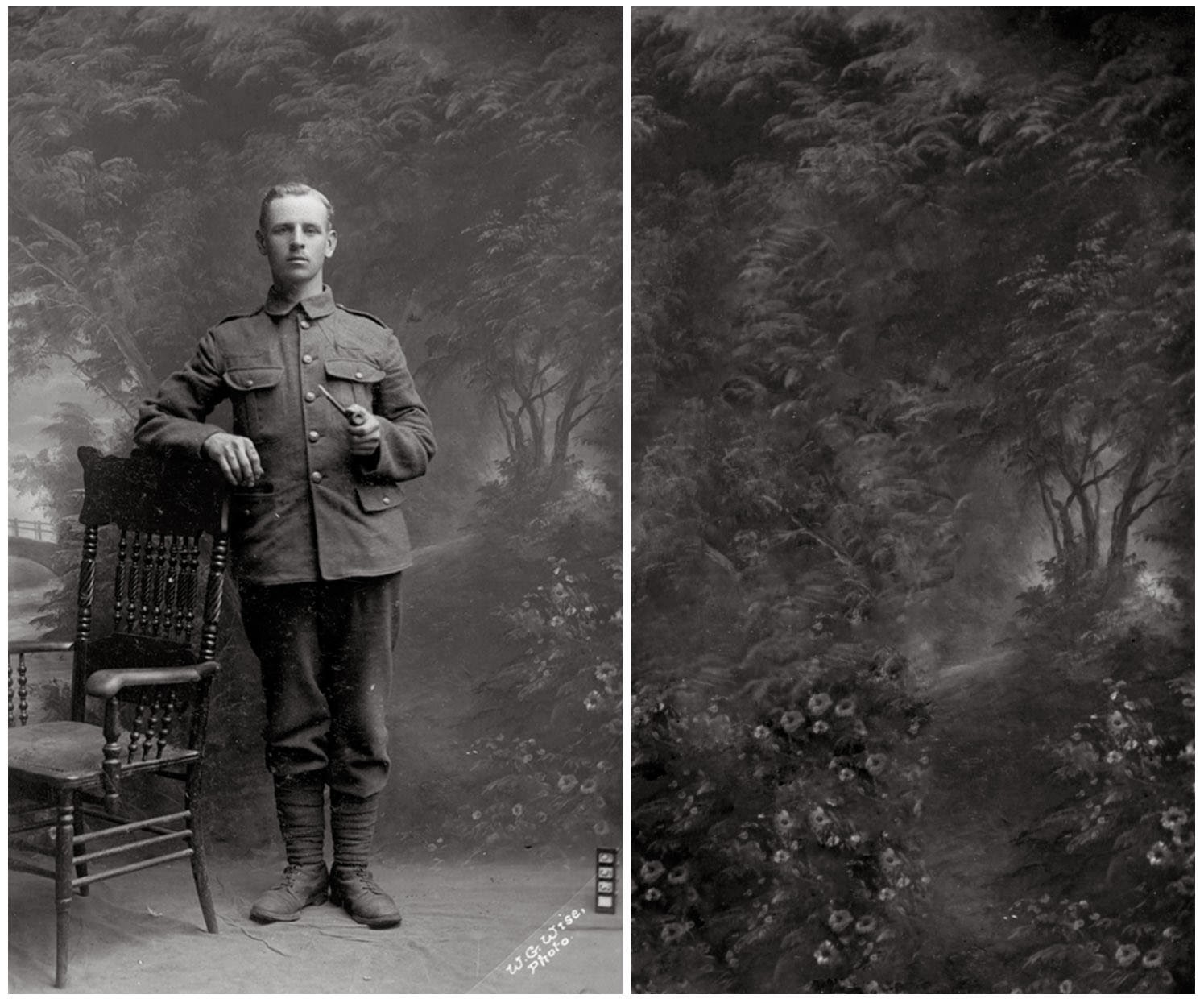

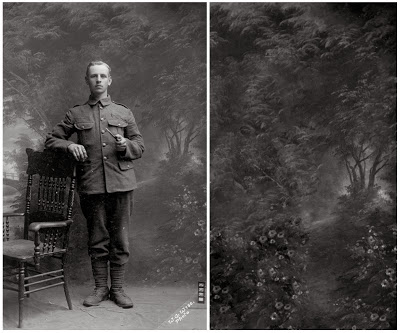

I’ve been thinking these last few weeks about a new body of work based on the First World War. For a long time – as will be evident from my blog – I’ve been looking at ways of using the backdrops of numerous World War I postcards.

A quote from Paul Fussell has been especially helpful in this regard.

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

The images on the backdrops are these proposed moments.

As a contemporary artist living so long after the war, it is of course impossible for me to create works about the war itself. What I can do however is comment on my relationship to the war (and those affected by it) by creating scenes – pastoral scenes – which use as their starting point the backdrops of World War I postcards.

The pastoral will, therefore, be articulated through the language of war.

These pastoral images will, predominantly, be woodscapes based on places I have visited over the last few years including Hafodyrynys (where my great-great-uncle, Jonah Rogers (1892-1915) grew up), Verdun and the Somme. They might contain – to quote Rilke – ‘…temple columns, ruins of castles’ as per the slightly less pastoral backdrops. They will be devoid of people; the soldiers absent as if they had melted into the backdrops – as if these pastoral scenes represent the Keening landscape of Rilke’s Duino Elegies.

As I’ve written before: it is this absence which the trees express so silently, so eloquently. As Rilke so perfectly puts it:

‘Look, trees exist.

The houses we live in continue to stand. Only we

pass away like air traded for air and everything

conspires to maintain silence about us, perhaps

half out of shame, half out of unspeakable hope.’

The woods I paint will be based, as I’ve said, on those places I have visited as well as those idealised scenes in front of which the soldiers stand in the postcards. They will be – as Richard Hayman puts it – woods “poised between reality and imagination…” – shame and unspeakable hope.

Again as I’ve written before: After the war, the sense of emptiness must have been everywhere. Every insignificant moment – barely acknowledged before the war – now pregnant with a sense of incomprehensible loss. The world, outwardly the same, had shifted just a little, but it had taken the lives of millions to push it there.

There is in this text a sense of absence but also of movement, of continuation – however slight or small (something I want to record in my work). And there’s a link between this and a quote from William Wordsworth who wrote in his Guide to the District of the Lakes: we can only imagine ‘the primeval woods shedding and renewing their leaves with no human eye to notice or human heart to regret or welcome the change.’ I somehow want to turn this quote on its head and borrow from Rilke, who in his Duino Elegies describes the towering trees of tears. I want to paint scenes where there are no people, but in which their absence is recorded, primarily by the trees silently remembering.

“The painter sees the trees, the trees see the painter.”

Chaos Decoratif

Paul Nash Quote

“Here in the back garden of the trenches it is amazingly beautiful – the mud is dried to a pinky colour and upon the parapet, and through sandbags even, the green grass pushes up and waves in the breeze, while clots of bright dandelions, clover, thistles and twenty other plants flourish luxuriantly, brilliant growths of bright green against the pink earth. Nearly all the better trees have come out, and the birds sing all day in spite of shells and shrapnel…”

WWI Backdrops

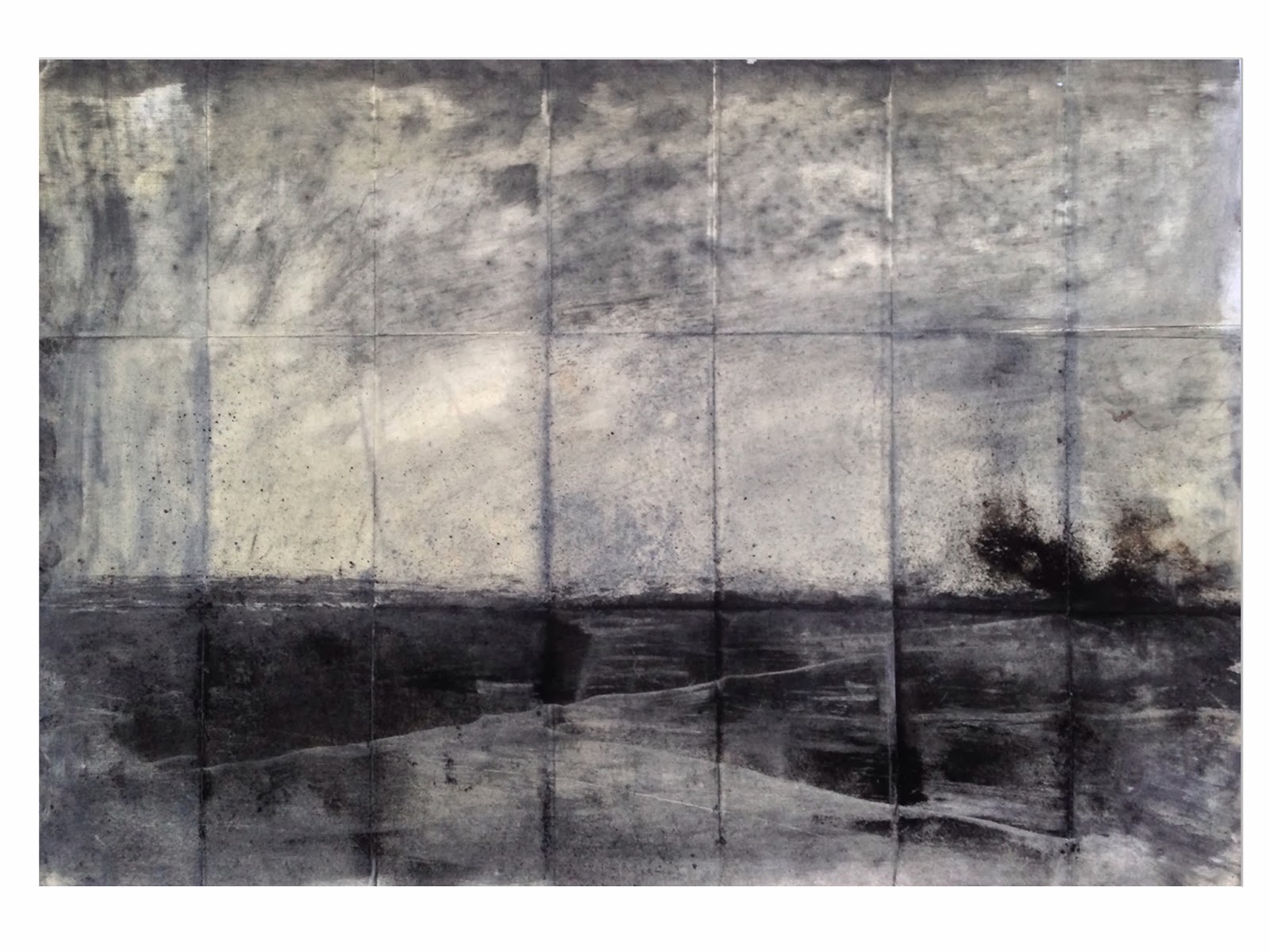

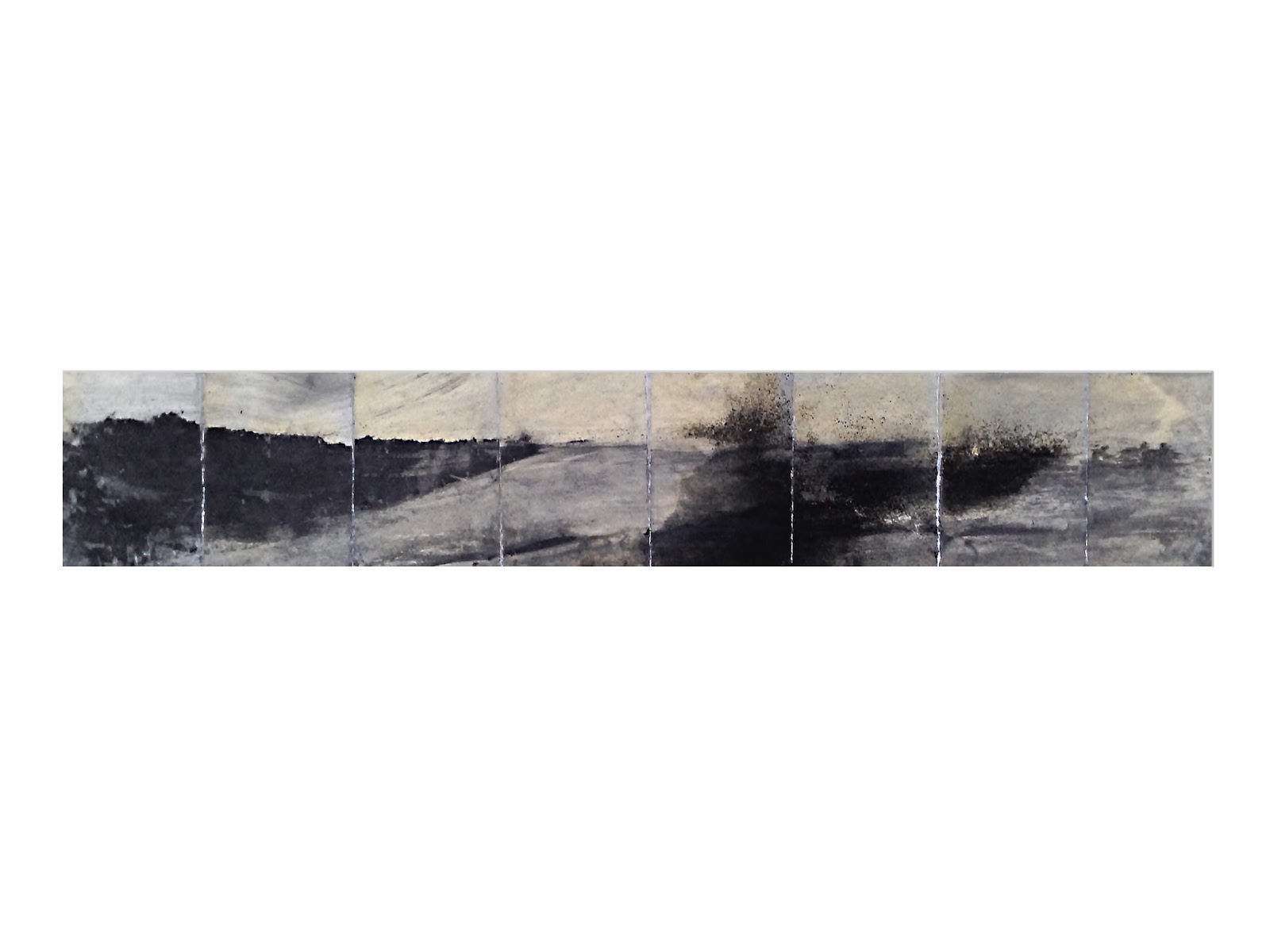

Heavy Water Sleep (Paintings) III

I worked again tonight on the studies for Heavy Water Sleep, working in landscape elements such as trees and sky. The original text from which the words are taken, ‘Pilgrims of the Wild’ by Grey Owl, is set chiefly in the forests of Canada. And in the ‘secondary text’ which inspired the work in the first place, ‘The Diaries of Adam Czerniakow’ there is a moving passage in which, following a visit outside the Warsaw Ghetto to the woods of Otwock, he writes simply, ‘… the air, the woods, breathing.’ Trees then seem integral to the work and have indeed been a recurring them in much of my work, particularly work to do with the Holocaust and World War I.

I wanted then to use trees in these works and found myself using a stylised form which I’d scribbled one day in my notebook based on lines you find in Family Tree diagrams.

This symbolic tree was in part inspired by some work I did on the First World War in which I used the dividing lines on the backs of original wartime postcards to symbolise the bond between the anonymous individuals who died in the war and their families back at home. These ‘T’ shaped divides reminded me of photographs in which hastily dug graves were marked on battlefields with crude crucifixes. I therefore created landscapes (based on my visits to battlefield sites on what had been the Front) and used these T-shapes to represent graves.

From these T-shapes I derived the forms for the trees below.

The link between them and the Ts above is an obvious one – even more so when one considers the original inspiration for this work.

Heavy Water Sleep (Paintings) II

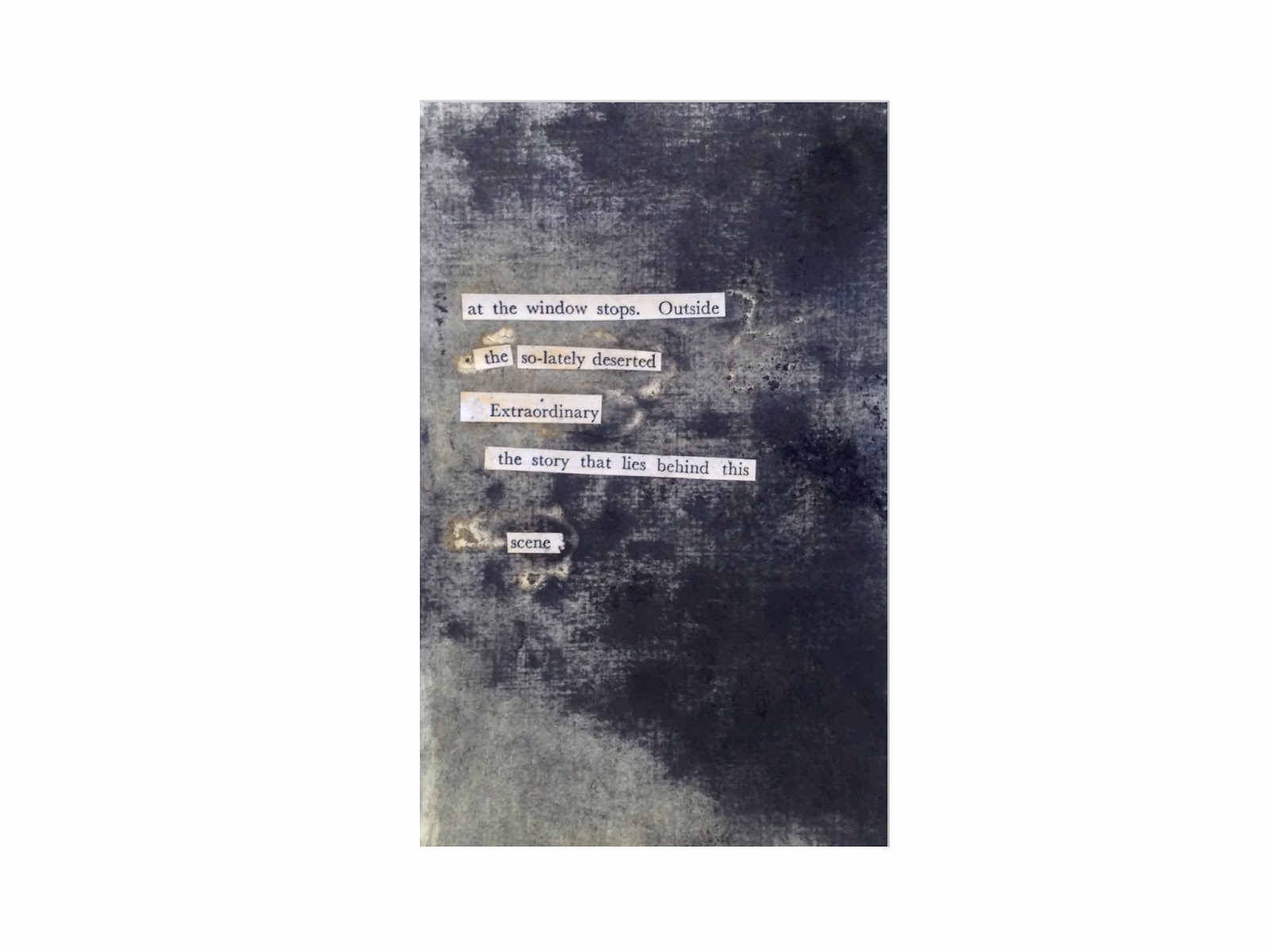

I worked again last night on the ‘Heavy Water Sleep’ paintings, continuing to concentrate on the texture. For the first board below I used a white acrylic paint mixed with an acrylic modelling paste.

The words are too chaotic in this one and the paint has dried very matt. I could add some gloss medium but it would make much more sense to use oil paint which I will for the final versions. I will add another layer to the painting above later.

Having completed this painting I worked again on the one I did yesterday.

I like how the words are slightly more obscured now and much prefer their more ordered placement. The next thing I want to try is keeping the lines of the pages together rather than placing them in a random fashion.

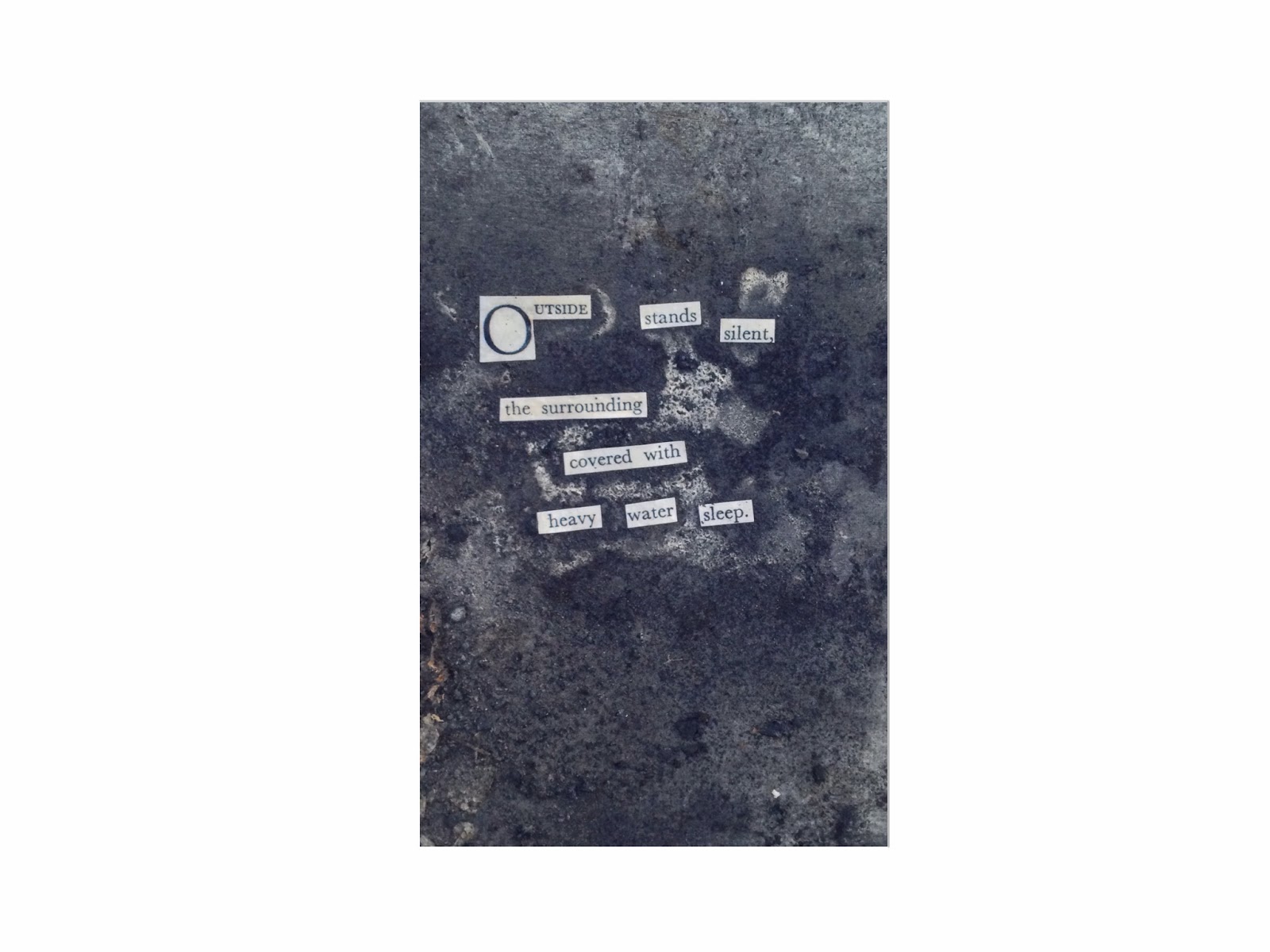

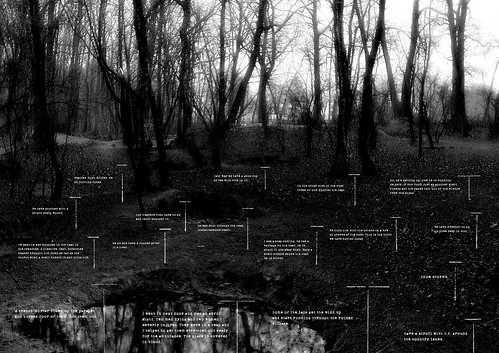

Heavy Water Sleep (Paintings)

I’ve started work on a new series of paintings based on the Heavy Water Sleep work I’ve been doing over the past few years. The idea is to create a series of paintings based on the idea of the words being a trail in a landscape (in turn derived from the idea that the book is a kind of map, leading me through the landscape of the past). The words from each page will be cut out with most painted over either wholly or in part. The words which make up the ‘poem’ of each page will be left, as per the image below.

The above sketch shows how the words might be placed.

What I realised after completing this sketch is how important it is to create a sense of depth in the work. At the moment the words are raised upon the surface, whereas they need to appear ‘sunk’ into the paint layer like footprints in the snow. Furthermore, the picture plane needs to be much bigger to give a greater sense of space – of wilderness; after all, this work represents the idea of the past as a place.

I shall continue – fo the time being – working on this scale in order to get the textures right, then progress to a larger canvas.

I suppose the ‘feeling’ I want to achieve with these paintings is that of the lone traveller, following in the footsteps of someone long since gone, and the one landscape painter who comes to mind is Caspar David Friedrich, two of whose pictures are reproduced below:

Of course I’m not aspiring to create something that looks like these paintings, but something which instills within the viewer the same sense of space, solitude and wilderness – not forgetting a sense of time’s inevitable passing.

Reading Roads

Introduction

In Wales in 2008 I walked a path along which my great grandfather had walked every day from his home to the mines in which he worked. He died in 1929 (as a consequence of his work) and all I knew of him, before my visit, were what he looked like (from two photographs) and things my grandmother had told me. But on that path I felt I found him on a much deeper level. The feel of the wind, the way the clouds moved, the sound of the trees and the line of the horizon were all things he would have experienced in much the same way. It was as if these elements had combined to ‘remember’ him to me.

As a consequence of my walk, the line which linked us on my genealogical chart changed to become instead a path, for when I follow lines in my family tree from one ancestor to the next and find myself at the end, so that path in Wales had led to my being born. That path on which I walked for the very first time, was as much a part of who I was as my great grandfather: “places belong to our bodies and our bodies belong to these places.” [i]

Roads (paths, tracks and traces) have become an important part of my research and it was whilst reading Edward Thomas’ poem Roads that I found connections between what he had written and what I was thinking. I’ve reproduced the poem below, and where necessary added my thoughts.

Roads by Edward Thomas (1878-1917)

I love roads:

The goddesses that dwell

Far along invisible

Are my favourite gods.

Roads go on

While we forget, and are

Forgotten like a star

That shoots and is gone.

The reference to stars (or a star) in this verse, reminds me of a quote (to which I often refer) from Roland Barthes’ book Camera Lucida, in which he writes:

“From a real body, which was there, proceed radiations which ultimately touch me, who am here; the duration of the transmission is insignificant; the photograph of the missing being as Sontag says, will touch me like the delayed rays of a star. A sort of umbilical cord links the body of the photographed thing to my gaze – light though impalpable, is here a carnal medium, a skin I share with anyone who has been photographed.”

On this earth ’tis sure

We men have not made

Anything that doth fade

So soon, so long endure:

The hill road wet with rain

In the sun would not gleam

Like a winding stream

If we trod it not again.

They are lonely

While we sleep, lonelier

For lack of the traveller

Who is now a dream only.

From dawn’s twilight

And all the clouds like sheep

On the mountains of sleep

They wind into the night.

The next turn may reveal

Heaven: upon the crest

The close pine clump, at rest

And black, may Hell conceal.

Often footsore, never

Yet of the road I weary,

Though long and steep and dreary,

As it winds on for ever.

Helen of the roads,

The mountain ways of Wales

And the Mabinogion* tales

Is one of the true gods,

(*In the tale of Lludd and Lleuelys from the Mabinogion, you will find the following text: “Some time after that, Lludd had the island measured in length and breadth; the middle point was found to be in Oxford. There he had the earth dug up, and in that hole he put a vat full of the best mead that could be made, with a silk veil over the surface. He himself stood watch that night.” I discovered this passage whilst researching my Welsh ancestry, and being as I am from Oxford, found it rather appealing.)

Abiding in the trees,

The threes and fours so wise,

The larger companies,

That by the roadside be,

And beneath the rafter

Else uninhabited

Excepting by the dead;

And it is her laughter

At morn and night I hear

When the thrush cock sings

Bright irrelevant things,

And when the chanticleer

Calls back to their own night

Troops that make loneliness

With their light footsteps’ press,

As Helen’s own are light.

Now all roads lead to France

And heavy is the tread

Of the living; but the dead

Returning lightly dance:

Whatever the road bring

To me or take from me,

They keep me company

With their pattering,

Crowding the solitude

Of the loops over the downs,

Hushing the roar of towns

And their brief multitude.

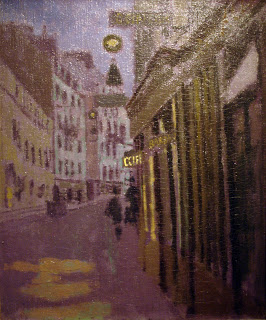

The rue Notre-Dame des Champs, Paris by Walter Sickert

The photograph below is a rather poor reproduction of a painting hanging in The Ashmolean museum, Oxford. It is perhaps, my favourite painting in the museum. Painted by Walter Sickert (1860-1942), it’s one which I have stood before for some considerable time, not least quite recently in order to write the following.

In my previous entry, regarding Cy Twombly’s Panorama, I discussed, albeit briefly, how it was quite impossible to fully appreciate a painting through a reproduction. Of course that much is obvious, but I wanted to write about this particular work to see just how differently I perceived it compared with the work by Cy Twombly, which, as I say, I’ve only ever seen in a book.

As can be seen from the photograph, one of the things I noticed straight away about this painting was the light reflecting off its surface. Not really anything to do with the painting perhaps, but, nonetheless it forced me to move, to find an angle where I wouldn’t be dazzled, and by doing so, I discovered something about the painting itself. What’s important here, is the fact that a painting isn’t just a surface on which paint is applied (although the appreciation of surface and texture can only be attained when faced with the real thing). Instead, a painting is as much about the space around it. Of course, Walter Sickert would have no idea that his painting would one day grace a wall in the Ashmolean museum, dazzled by the lights. But he would have walked whilst painting it, or rather moved before the easel. He would have stood in front, to the left, to the right, and this movement in the act of painting is, I believe, important in the act of viewing and appreciating the result.

So what do we see in this work? Well, it’s a road in Paris (the rue Notre-Dame des Champs), one on which the painter John Singer Sargent had a studio. Given the muted palette and bruised sky, the picture shows a scene from about that time of day when the night begins removing all the colours from the world, when the last light in the sky, makes all manner of colours that seem to last for just a few seconds. It’s a wet end to a day that’s more than likely seen nothing but rain. The concertinaed facades of the shops with their heavy paint dragged down the surface, the downward strokes of the windows in the buildings opposite and the vague forms from which the scene’s almost entirely comprised, all suggest the fading light and drenched air of an autumn or winter evening.

There are puddles in the street which soak up the sickly light of the cafe like a man with a sponge mopping up blood after a brawl. The road is somewhat sickly and the light of the cafe offers us a refuge from whatever is coming just around the corner. Two or three figures stand just ahead. Are they moving? Are they walking towards us? Away? It’s hard to tell. But a feeling of isolation, pervading the picture, is I believe augmented by their presence.

As I moved before the painting, shifting my weight from one foot to the other, the colours seemed to shift. The bluey-violet sky shimmered above the drowned buildings, and the reflections in the road revealed new colours the more I looked. Looking at the painting in the flesh, I felt – compared with looking at the reproduction above – that my eyes had to move in order to cross from one side to the other. In a reproduction, the spaces are of course greatly reduced and everything can be seen or grabbed in an instant. In the flesh (and this painting is very much about the physicality of the world) you look as you might when standing somewhere in town. You look with more than just your eyes; you experience the painting with your body; one that stands alone before the canvas.

Returning for the moment to the glare of the lights, I found that when I looked at the painting from the right hand side, the glare subsided, and that all that remained were just a few specs where the paint was raised above the rest of the surface. Furthermore, from this position, the painting seemed to open up, as if the concertinaed lines of the shop facades were being pulled, expanding like bellows. Here, the street seemed to pull me on. Standing directly in front, it almost seems about to collapse upon itself.

I’m not trying to suggest that this is all deliberate on the part of the artist, but to emphasise the fact that the act of looking at a painting is a physical experience. Sickert would have known this street, he would have recalled what it was like to stand there. He would have moved before the canvas as he painted, and, as a viewer, the way I stand and move before the canvas reflects that. It is, in the end, the only way to get to know art.

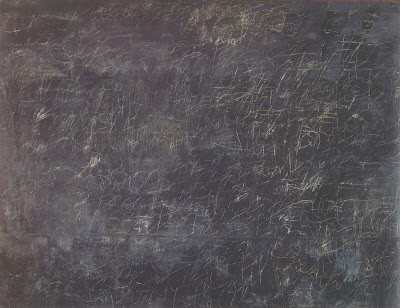

Panorama by Cy Twombly – Part 1

The first painting I have chosen is Cy Twombly’s 1955 painting Panorama.

Something which in a moment was possessed with meaning, means nothing now, and all those moments, layered one on top of the other, create as a result, a palimpsest of ambiguous symbols signifying a strange kind of nothingness; a presence which at the same time is also an absence. People come and people go, and in some respects, this painting is for me a work about time – about the simultaneity of what I’ve just described: presence and absence.

Dust Motes

Totes Meer

I was watching The Culture Show last night and during a piece on a Paul Nash exhibition at the Dulwich Picture Gallery I was struck by the following painting, Totes Meer which can be seen below.

It shows a heap of German planes – those brought down over England, ready to be sorted so the metal could be salvaged. For Nash, it was a scene to inspire Patriotism, but what interested me – at least initisally – was the fact this scrap heap had been in Cowley, not far from where I once lived.

I am of course interested in the past, the wreckage of the past if you like, and how we can salvage parts to be reused in the present day, so therefore this painting has a great deal of interest for me; not only because of that but because of the scrapheap in Cowley.

Front and Back (2nd Mons)

I started work on a new painting today based on the work I made as part of my Mine the Mountain exhibition. This piece, Front and Back (2nd Mons), uses the ‘T’ shaped divides on the backs of postcards which are then stencilled onto the canvas, already painted with a generic battlefield scene. I would really like to paint this on a large scale but we’ll see how this goes first.

8th May – A Painting

This is the second day of working on the painting which will be shown as part of my ‘Mine the Mountain‘ exhibition. The title, 8th May, alludes to both my date of birth and the date my great-great-uncle, Jonah Rogers, was killed in action at the Battle of Frezenberg Ridge (Second Battle of Ypres) in 1915.

When the painting is shown it will be veiled to represent the death of my ancestor. When the veil is lifted, the work will of course be changed to represent my own coming into being. Veiled, the scene is obfuscated, hidden from the deceased to prevent his getting lost on his way to the next life; when lifted, the scene is presented as I remember it, or know it.

Dark Tourism Conference

This morning I went down to St. John’s college to view a room in which I’ve proposed to exhibit work during a conference to be held there in April. The conference is titled ‘Travel and Trauma: Suffering and the Journey’ with a sub-heading; ‘A Writing Journeys and Places Interdisciplinary Colloquium,’ and therefore I wanted to show something which would fit in with this theme. Even though much of the work on my MA has already dealt with this subject and would be entirely appropriate for this event, I have in mind to do something new. And so, I went to view the space to see what possibilities it might afford me.

The space itself is a room in a modern block and what I noticed right away was that there was a lot of glass with, and as a result, a good view of the outside. I asked if the outside might be used and there seemed to be no objections to this. However, the more I thought about the space, and the more I thought about the conference title, the more I saw myself writing – creating a work with text. I thought of some of the work I’d done in the past, and the painting I made after my visit to Auschwitz gave me an idea.

The text written across the painting and resembling wire immediately made me think of writing in a similar style across the large windows in the room (perhaps with a black chinagraph pencil). But what would I write? Whatever it was would have to be relevant to the space and the idea of tourism and after thinking for a while I considered again the view beyond the window – the reality of what was on the other side of the glass. I thought of writing a history of St. John’s college but then considered instead, the idea of writing a description of what was actually there outside, framed by the window at which those reading the text would be standing; reading and yet blind to the reality of what was in front of them.

So what would this mean: people reading the text describing the reality of what was there ahead of them, blind to that reality because of the text/wire behind which they are held? For me it signifies the impossibility of getting near to the reality of an event through writing/reading about and expriencing a place, but saying that, it wouldn’t be a work suggesting the futility of such experiences – far from it – but it would hopefully raise questions about our role as tourists.

Canaletto

Yesterday, prior to meeting a friend, I paid a quick visit to the National Gallery, a place of which I can never tire (just the fact one can enter as freely as one enters a shop never ceases to amaze me). I had little time, around 15-20 minutes and so I headed towards the 18th century, and as I walked I saw a sign pointing the way to Venice. Having not long returned from the city, I made my way in that direction, checking my watch to keep an eye on the time and quickly found myself there again, in the mind of a certain Canaletto. Of course, I am familiar with Canaletto and his great views of the Grand Canal, but it was, as always a pleasure to see them again. And with Venice still fresh in my memory, wet like paint, I found the canvases teaming with life; the blue two centuries old sky which I had seen just two weeks ago, the turquoise canals and the buildings, which always put me in mind of old yet elegant widows. Yet, it was two smaller works which I found the most appealing. Firstly, ‘Venice: Piazza San Marco and the Colonnade of the Procuratie Nuove’ painted in about 1756, and secondly ‘Venice: Piazza San Marco,’ painted again around 1756.

I paid little attention to the dates (I didn’t have much time as I said), but recognised there was something melancholic about these works when compared with others I could see (such as the Regatta on the Grand Canal).

In my mind, I can still hear Venice, I can hear the sounds of these very colonades, I can feel the lapping shadows, and when I look at the paintings above, those sounds (the murmuring voices, the footsteps chipping at the ground) become those of the people in the paintings, of men, women and children who have been dead for two centuries. One can almost imagine, the man in the green cape holding his coffee (‘Venice: Piazza San Marco’) still standing there now, listening in on the conversations of the living, quite unaware of the passing of time, of the passing of his own life.

And it is interesting, and indeed appropriate, that not far from the place painted by Canaletto in these two late works, Bill Viola’s meditation on life and death was installed in the Chiesa di San Gallo. This work, with its use of water as a ‘dividing line’ between life and death has no more appropriate place to he shown than Venice, and the more I think about the city, the more I see it as a place where life and death coexist; indeed, the very symbol of Venice, the Gondolier has a role to play. Amongst the crowds thronging the Riva Degli Schiavoni, who’s to say the dead don’t stand amidst the tourists – the man with his coffee cup – awaiting the Gondoliers who will ferry them to the next place. Perhaps it is the city’s almost supernatural existence, which lends the place this other-worldly air. As Paul Morand writes in somewhat unconventional biography, ‘Venices’:

” Venice did not withstand Attila, Bonaparte, the Hapsburgs, or Eisenhower; she had something more important to do: survive; they believed they were building upon rock; she sided with the poets and decided to be built on water… Within her restricted space, Venice, situated as she is in the middle of nowhere, between the foetal waters and those of the Styx encapsulates my journey on earth…”

Day 10

Finished priming the canvas and then painted a layer of Paynes Grey on top. Over this I’ll rub some white before working in the graphite powder. Into this I’ll then scratch the outlines of Loggan’s 1675 map which I will attempt to project on top.

I also did another walk following the same route and this time crossed out the words that were no longer appropriate (for example, objects that were no longer visible). As I did this, I decided to add new words that were appropriate to today.

The new list of words now reads:

voices

the sun

engine starts

Leffe

zebra crossing

waiting

boarded windows

remnants of posters

French market

a man on a bike

a dog being walked

all routes

missing letters

pencilled ‘e’

blue car

squeaking brakes

a woman carries a package

red lights

weeping willows

green mound

red man

cyclists wait

open window

Guinness Time

green man

20 zone

pull pull

discarded bottles

old confetti

cigarette butts

a man in sunglasses

crooked shadows

fire extinguishers

discarded blanket

weeds in pots

a man eats

the sun

a flag hangs

empty racks

doorbells

dirty water

orange jackets

taxi

lifebuoy in the river

cementing pavement

a broom

plastic bottle

two men in ties

pile of sand

gravel

weir

stone tower

scaffold

danger – high voltage

cygnet

sun sparkles

water sounds

lifebuoy

warning!

measuring post

submerged traffic cone

drowned bicycle

the stain of a splash

shopping trolley

birds twitter

a ladder

a barrier

a signpost

bright sun

hooded top

people talk

birds twitter

footsteps

CCTV

arrow

broken green glass

ornate gate

roar of bus

music

concrete

shadow

a man pulls up sleeve

a woman sits

tables and chairs

glass ashtray

trees

tinted windows

engine ticks over

bus shelter

green plastic bag

a woman eats a baguette

two yellow markers

green spire

amber light

the sound of a crossing

footsteps

blue plastic bag

graffiti

OX4

blue peeling door

two men talk

green door

satellite dish

sharp shadows

a drain

sound of keys

man opens green door

lamppost no.4 peers

old stone walls

lamppost no.6

a man talks on a phone

gutter

half-painted

weeds

three young women

locks for nothing

a suitcase pulled

a blue door

a blue door

a plastic bag on a saddle

a woman takes a photo

a man checks the films

a taxi

a sapling

black plastic bag

pigeons

checking tickets

a phone rings

fat stomach

bottle top