From the video of ‘Enjoy the Silence’ by Depeche Mode.

Black Mirrors

The black and white veils in question are those with which the 100 mirrors I will exhibit at The Botanic Gardens will be covered. At the moment I’m still unsure as to which to go for. The black veils are the most obvious in terms of the meaning they generate, black being the traditional colour of mourning in this country. White however is the traditional colour of mourning in Jewish culture (so I understand) and a 100 mirrors veiled in white and placed in a grid formation would have the resemblance of a military cemetery which would tie in with the work I’ve done on World War 1 in that they would look a little like a military cemetery. However, having recently read a ‘chapter’ in Bill Viola’s book, ‘Reasons for Knocking at an Empty House,’ there seems to be a case for looking at the black veils again.

In the following passage, Viola discusses the eye and the black mirror of the pupil:

Socrates (describing the Delphic inscription ‘gnothi seauton’): I will tell you what I think is the real advice this inscription offers. The only example I find to explain it has to do with seeing. … Suppose we spoke to our eye as if it were a man and told it: “See thyself” . . . would it not mean that the eye should look at, something in which it could recognise itself?Alcibiades: Mirrors and things of that, sort?Socrates: Quite right. And is there not something of’ that sort in the eye we see with? … Haven’t you noticed that, when one looks someone in the eye, he sees his own face in the center of the other eye, as if in a mirror:’ This is why we call the centre of the eye the “pupil” (puppet): because it reflects a sort of miniature image of’ the person looking into it… So when one eye looks at another and gazes into that inmost part by virtue of which that eye sees, then it sees itself.Alcibiades: That’s true.Socrates: And if the soul too wants to know itself, must it not look at a soul, especially at that inmost part of it where reason and wisdom dwell? …This part of the soul resembles God. So whoever looks at this and comes to know all that is divine – God and insight through reason – will thereby gain a deep knowledge of himself.

The black pupil also represents the ground of nothingness, the place before and after the image, the basis of the “void” described in all systems of spiritual training. It is what Meister Eckhart described as “the stripping away of, everything, not only that which is other, but even one’s own being.”

In ancient Persian cosmology, black exists as a color and is considered to be “higher” than white in the universal color scheme. This idea is derived in part as well from the color of the pupil. The black disc of the pupil is the inverse of the white circle of the Sun. The tiny image in “the apple of the eye” was traditionally believed to be a person’s self, his or her soul, existing in complementary relationship to the sun, the world-eye.

There is nothing brighter than the sun, for through it, all things become manifest. Yet if the sun did not go down at night, or if it were not veiled by the shade, no one would realise that there is such a thing as light on the face of the earth… They have apprehended light through its opposite… The difficulty in knowing God is therefore due to brightness; He is so bright that men’s hearts have not the strength to perceive it… He is hidden by His very brightness.

Al-Ghazzali (1058-1111)

So, black becomes a bright light on a dark day, the intense light bringing on the protective darkness of the closed eye; the black of the annihilation of the self.

Fade to black…

[Silence]”

Through reading this passage, my question as to whether to choose black or white veils for the mirrors was answered and a title suggested for the piece. These mirrors have always served to represent the individuals of the past and our reflections ourselves in the present. They are an attempt to see ourselves as those in the past once saw themselves, a real as we are today. When Viola writes how the closer he gets to have a better view into the eye, the larger his own image becomes, thus blocking my view within, I can take this as being analogous with the difficulties faced by my attempt at seeing individuals in the past where my view, the closer I look is necessarily blocked by my own self (although of course the theme of my work has been to know past individuals through knowing oneself).

This passage also reminded me of a passage from Rilke’s ‘Duino Elegies’ where in the Eight Elegy he writes:

“Lovers – were it not for their loved ones

obstructing their view – they come near it

and are amazed… As if by some mistake,

it opens to them, there, beyond the other…

But neither can slip past the beloved

and World rushes back before them…”

Verdun

On 26th April I visited the battlefields and sites of Verdun. The name, like that of the Somme and Ypres, calls to mind visions of unimaginable horror; thousands upon thousands of men turned into names carved in monuments in towns throughout Europe, or lost completely, names and all, in the churned and pulverised fields. In my imagination, such places are always wet, cold, dark and desolate, as frozen in their appearance as they are fixed in old black and white photographs.

I won’t at this point discuss the battle’s history, suffice to say it’s a place in which around 500,000 men lost their lives, a figure which like so many grim statistics (I’m thinking here of my work on the Holocaust) is almost impossible to imagine (as much as it’s impossible to correlate). 26,000,000 shells rained upon the battlefield, six shells for every square metre. But difficult as these facts are to process, we must at least try.

Having arrived in Verdun, we stopped the car at a track leading into a wood and no sooner had we started to walk amongst the trees than we became aware of the undulating ground; the shell craters and trenches, around and from within which this new wood had grown. At once we recalled the craters and trenches of Sanctuary Wood in Ypres, but the contrast between the two was clear; in Sanctuary Wood the trenches had been, at least, ‘over-preserved’ (some suggest they were dug for tourists after the war) but here they’d remained untouched since the end of hostilities. They were rounded and smoothed, and all the more powerful. At Sanctuary Wood, the whole place had the feel of a playground, whilst in this wood, the peace and quiet provided a stark counterpoint to the horrors of war.

This counterpoint came in the birdsong and the colour of the sky, which on what was a glorious day was tinted by the brown of the trees and last year’s leaves filling the craters and trenches; a curious bruising as if a part of the dusk was somehow stained upon it. And between the carpet of leaves and the blue of the sky, was the green of this year’s growth; the whole scene a complete contrast to what the name, Verdun, had until now conjured in my mind. This place was simply beautiful.

Save for a few tourists, we walked the woods alone, and yet, even then, the trees like those we’d encountered at other sites of trauma, seemed more than what they were. But whereas those which grow in Auschwitz-Birkenau and Belzec are strangely complicit in the events of the past, those in Verdun had grown from its wreckage; they did not hide what happened there. And stranger still was the sense that in this place Mankind was older than nature; Man had shaped the ground through his own destruction; he had made the void – the quagmire of mud – from which nature had risen, giving the trees a human quality, as if they carried with them the memory of all who fell – as if they were the fallen soldiers. And the resilience of Nature, it’s ability to rise from such appalling devastation, was one of the most striking aspects of our visit; despite the human feel of the trees, I realised how small humans are, even when they are made big through war. No matter what we do, Nature will in the course of time return. Long after we have finally gone, she will still be here, just as she was that day, in blue sky and birdsong, and as such, to walk through the woods was like being the last two people left on Earth.

This scarred idyll was littered with other wartime detritus; the pillboxes within which men would hide, seeking out their fellow man beyond the apertures through which their guns were trained. They sat like concrete bells, still ringing with the war, like the ringing heard in silence, after exposure to something loud. (I am reminded here of the idea of sympathetic vibrations, where when a bell is struck, another bell across the room begins vibrating, giving off the same sound. These pillboxes which litter the landscape around Verdun, and which we saw in Ypres, seem to contain within their walls and deep impenetrable interiors, a sound which finds sympathy in all the others. I can imagine these vibrations ringing in sites all across the world, again long after man has gone.)

Having recorded the sounds of the birds (and on playback I notice the insects – and I start to think of flies trapped in amber) we left the wood and made our way to Fort Vaux, the second to fall in the Battle of Verdun and a place I will return to later.

This persistence of Nature was nowhere more apparent than in one of the ruined villages which we visited towards the end of the day. There was nothing left of Fleury-devant-Douaumont save for the street names preserved on signposts along with signs indicating where there’d been a farm, the cafe, Town Hall and the workshop of a weaver.

One of the interesting things about the numerous ruined villages is how they each have a Major, a post created to preserve the memory of the place as well as those who lived there. Like the woods, the landscape was blistered beneath the lush grass, undulating like immeasurably slow ripples following the impact of thousands of shells. It was pockmarked with craters some of which had filled with water to make ponds, beautiful beneath the dappled shade of the trees. Again, one had the feel of Man being older than Nature, with the new wood growing out of what remained of the village; despite the unimaginable numbers of shells which ploughed the soil, the sheer number of dead, the poison of the gas used in the battle, the ground had somehow made this beautiful landscape. And just as a corpse can tell us much about its demise through what nature has written upon it – the time of death for example – so the woods grown out from the corpse of the landscape speak of the time that has passed; and here is the curious enigma of the Great War. Despite the fact that almost a hundred years separates us, it doesn’t seem that long ago.

Fort Vaux is a name synonymous with the suffering, endurance and the bravery of the soldiers who fought there. Even after the French were forced to surrender, the Germans presented arms as a mark of respect. The following is an extract from H.P. Willmott’s book on the First World War.

“The German bombardment of the Fort began on June 1st 1916, at one point firing shells at the rate of 1,500 to 2,000 of the per hour. Inside were 600 troops under the command of Major Raynal. Just before dawn on the 2nd the barrage stopped and two German battalions moved forward. By mid-afternoon they had overwhelmed the defenders and occupied a large part of the superstructure. Raynal was determined to resist, and he and his men withdrew to the underground corridors where a grim battle was fought in the darkness with grenades and machine guns. On June 4th the Germans used flamethrowers in an attempt to drive the French out with asphyxiating black smoke…”

It’s a curious shell, a skull like structure cut into the rock which belies the horrors it has witnessed. Standing on top, one could see why it was so important, commanding spectacular views of the surrounding countryside and here, the contrast between the view of the tourist and that of the soldier becomes stark. What would they have seen from this same position? Hard to imagine that it was such a wasteland.

From Fort Vaux we made our way to the Memorial Museum and then to the Douaumont Ossuary. At the Museum, there was one object in particular which interested me, and that was a notebook containing handwritten translations of English words into French.

The first line is the translation for Dead; Mort.

The structure of the ossuary is very much of its time and has the appearance of something which wouldn’t look out of place in Fritz Lang’s vision of the future, Metropolis. And this fact reminds us that it was just twenty years later when Europe and the world would be plunged into yet another catastrophe, indeed, during our journey around Verdun, we found evidence of this catastrophe in a memorial to 16 people killed in the second world war whose mutilated bodies were found dumped in a ditch which itself formed their memorial.

From the top of the tower, one is again presented with spectacular views of the battlefields and again one can’t imagine what it would have looked like in those dark months of 1916. The tower itself houses the Victory Bell and the Lantern of the Dead which shines out over the battlefield.

Most of the structure is taken up by the 137 metre long cloister where each tomb shows a precise area of the battlefield from where the bodies were recovered. What one does notice – especially on a warm sunny day like that on which we visited – was how cold it is inside. One expects it to be colder given the thick stone walls, but there is something of an extra dimension to the chill, one is made all the more aware of being in the presence of the dead. And yet, this cold defines the living, it shows up our breath and for me, this was one of the most powerful aspects of the building.

Outside the ossuary, through a row of small windows, one can see the bones of the 130,000 dead entombed within. Seeing the piles of leg bones, shoulder blades, vertebrae and skulls, one is reminded of the randomness of war, the arbitrariness of death on the battlefield. Like numbers and lists of names, it’s hard to imagine that these mountain of bones were once thousands of individuals, just as walking amongst the graves of the 15,000 men in front of the ossuary, one cannot imagine that many dead. Multiply that number, that space by thirty, see where it stretches out into the distance, and one begins to understand – in part – the horror of the war.

But one can never know what it was really like, and that to some extent is the point. Would we want to? We must do everything we can to never know. The inability to contemplate such horror in the face of such natural beauty is exactly its power. What we see when we walk through the woods is in some respects the world as it was before the war, the world of better days as remembered by those caught in the ‘meat-grinder’ of battle. The trenches gouged in the ground and the shell-craters pock-marking the soil are reminders of a brutal past, and yet they are also a warning about the future.

Having left the ossuray we made our way into the town of Verdun itself. Music was playing from speakers attached to all the lamposts, and at the appearance of people dressed in costume and sporting masks, we realised we had come at the time of a carnival. But there was something sinister about these people, the way in which they were a part of the town but detached, within but without. Something about their featureless, anonymous faces; the way they looked at us but we could not look at them, just a version of their selves.

And seeing all these colourfully dressed people on the steps of the town’s huge memorial served to illustrate the continuity of life, but also the fact that those who died on the battlefields outside the town would have known brighter, happier, more colourful times, a juxtaposition which is everywhere in Verdun and which was to be found in the town’s Cathedral, itself hit on the first day of the battle – February 21st 1916.

The Cathedral still bears the scars of war, but on the inside, one finds again the colour.

Music and Text

As part of a new project, I’ve been looking at ways of creating musical scores. As someone who composes music but cannot read it, I find this particularly interesting inasmuch as I’m looking to write a piece of music but want to do so, not by ‘feeling’ the music as I’m playing it (as is how I normally do it), but rather, through a process of ‘writing’ it down first. The scoring should, furthermore, be linked with the theme of the piece. For example, for the music I want to write as part of my Tour Stories: Oxford Destroyed project, I’ve tried drawing remembered images of the city, blind on a piece of manuscript paper.

It was whilst making work for a project “The Ordinary Language of Freedom” that I became aware of how what I was doing (writing on a window) reminded me of the look of music – a link made manifest perhaps by dint of the fact I cannot read it.

And prior to this, music – and in particular, musical scores – surfaced towards the end of my work on the Dreamcatcher project, where I began to see the piles of string as unsung/unwritten notes and the net as an attempt to piece them together – to write, in effect, a score of unwritten music.

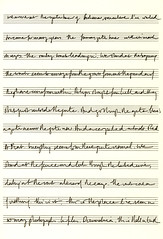

I began by considering what what one can derive from a blank sheet of manuscript paper. Comparing it with an ordinary blank sheet of paper there is clearly a difference. The staves somehow resonate, they make a sound even when there is nothing on them, and remind me of the silence one encounters in churches; pregnant with echoes (one thinks here again of Bill Viola’s discussion of sound in Chartres catherdral). When the text is written upon the staves (as above), the text becomes music, but of a different kind. The words are not words to be sung (that would be the case if the words were written beneath the staves and notes upon them) neither are they to be spoken. If the words are written beneath the staves without notation then they become neither words to be sung or spoken. They are not music. They are not simply text. They become lost.

Looking at some past text work I made as part of my OVADA residency (‘Wound’), I thought of repeating the work using manuscript paper.

The results were particularly interesting.

There is something about this piece which I find particularly resonant. The text is taken from a piece of writing I made following my visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau in which I describe the silence of the place; one, which like that in churches, I remember as being pregnant with the past. Looking at it closely, I was in fact reminded of mediaeval manucripts.

I need to explore these ideas more throughly, which in part I will do through a new project (6 Yards 0 Feet 6 Inches) and then, with a few ‘scores’ in hand, I will start to create some music based upon them.

Dreamcatcher IX

Thinking about the backdrop for the Dreamcatcher I have decided that it would be best to stick with just empty sheets of manuscript paper rather than bits of everything else. The trouble is I haven’t collected enough different types of paper and having just three things (manuscript paper, postcards and lined paper) makes it as a whole look a bit ‘cobbled together’ and rather contrived. Having just the manuscript paper however helps me to avoid this. Furthermore it makes for a stronger piece. With just the empty manuscript paper as a backdrop, the cut string would become just the unwritten notes, unsung music; and they would I believe be more pertinent to the theme of lost voices, silenced voices. There is something more human about these pieces of string being unplayed or unsung music.

One particularly interesting contrast is the idea of music (sung music in particular) filling a space. One can imagine the sound waves with the potential of filling a vast area and then the pile of unsung notes (unheard voices) piled in just a corner. There is the difference too in the quality of the two; the sound being light and the string being dense and heavy.

I am reminded here of something I read in Bill Viola’s collection of writing: ‘Reasons for Knocking at an Empty House. Writings 1973-1994’.

“Chartres and other edifices like it have been described as ‘music frozen in stone’. References to sound and acoustics here are twofold. Not only are there the actual sonic characteristics of the cavernous interior, but the form and structure of the building itself reflects the principles of sacred harmony – a sort of ‘acoustics within acoustics’. When one enters a Gothic sanctuary, it is immediately noticeable that sound commands the space. This is not just a simple echo effect at work, but rather all sounds, no matter how near, far or loud appear to be originating at the same place. They seem to be detracted from the immediate scene, floating somewhere where the point of view has become the entire space.”

I’m particularly interested in the idea of the net being a score of sorts, one that can be sung or played (I like the idea of the cello being used in this context, as this instrument, a mournful one in many ways, has often been described as being the closest sounding instrument (in terms of its timbre) to the human voice. If one was using the net as a score, what would one be playing? The lines of the string, the intersections (knots) or the spaces between?

In many ways, this takes me back to a research project I started, but on which I never worked that much called Pathways Project. And already a title has come to mind. Dead Light: Unsung.

Alsace

I have just returned from a visit to Luxembourg to see my girlfriend, during which time we took a trip to Alsace. As per usual, I had little idea as to what I should expect of the place, but had heard that it was particularly pretty. The traffic jam on the approach to Metz didn’t bode well, but once we were past this we made our way at a good pace towards our first destination. However, before reaching it, we passed through the village of Molsheim (not so far from our ultimate destination of Colmar) and if ever there was a word to describe it then pretty would be it. The weather was a little overcast, but nevertheless, the village’s obvious picturesque charm shone through.

It was we thought rather like something from of a fairytale. One would have hardly been surprised if Shrek had passed by on the street, followed by Donkey and Puss in Boots.

We stayed long enough for a quick stroll, during which time I snapped several pictures, and made our way back to the car. In truth I thought it was a one off, but driving on, we soon discovered that every village was a similar, chocolate-box place; one might have expected to eat the houses, let alone take photos of them.

All this however was in stark contrast to our next stop.

Before making our way to Colmar, we took a detour on a meandering road which led us up into the Vosges mountains. The scenery was breathtaking. The clouds fell and trees rose like arrows to pierce them, whilst the drop at the side of the took one’s breath and cast it over the edges of the road. After a twisting ascent, we finally arrived at the concentration camp of Natzweiler-Struthof.

The following is taken from the guide:

“On 1st May 1941, the Nazis opened the KL-Natzweiler concentration camp in a place called Struthof. Nearly 52,000 people from all over Europe were deported to this camp or one of hits annexes. 22,000 of them never returned. On the 23rd Novemeber 1944, Allied Forces discovered the site, abandoned by the Nazis in September 1944.”

It was here that Hitler’s architect Albert Speer surveyed the area and recognised its rich resources of red granite. A camp was therefore established so that slave labourers could be used to work in the quarries. It also housed large numbers of so-called Night and Fog (Nacht Und Nebel) prisoners, so called because they disappeared as if into the night or the fog.

The camp itself is dominated by a large memorial to the many who died here, including many Poles and members of the French Resistance. And, although not a Death Camp per se, the two barracks at the bottom (two of the few which now remain intact) reeked of death and untold misery. Even here, amidst the natural splendour and beauty of the Vosges, there is a room with a hole in the ground to let the blood run through, a white tiled morturary slab and white painted windows, not so much to stop people looking out, but to prevent anyone looking in.

It’s strange how they appear gagged; prevented from talking rather than seeing, and taken with the camp’s isolation, they serve to reinforce the silence which hangs over the place like the clouds.

Whether it’s because of the camp’s comparatively small size (certainly compared with somewhere like Auschwitz-Birkenau or Majdanek) or the relatively ‘smaller’ death toll, again compared with somewhere like Auschwitz-Birkenau, the sense of the individual was particularly apparent here – or at least, the sense of ‘individual death’. Perhaps the location – the natural geography of the place – helped foster this feeling, primarily through the sheer size of the landscape by which the camp is surrounded. As a visitor, you feel isolated, you are aware of yourself, and the sheer scale and colour of distance. The blue mountains rising from the horizon like massive cardboard cutout waves in which you might drown; you might well shout but little would be heard, and yet, in just such terrain, echoes rebound; voices and anguished cries from the past, directed at the future of which we are a part.

As with all visits to places such as this (Auschwitz, Birkenau, Majdanek, Belzec) it is the leaving that is most affecting, walking through the gate to rejoin the real world, something which in the case of Natzweiler Struthof, 22,000 people were never able to do.

From Natzweiler-Struthof, we made our way to the town of Colmar, home to the artist (as I was later to discover) Martin Schongauer (1448-1491). It would be, I was told by Monika, like Molsheim, but bigger and she wasn’t wrong. Having arrived in the evening and checked into our hotel, we went for a brief stroll, with the main aim of finding somewhere to eat, which we did in a very attractive courtyard.

It was clear that this was a beautiful town, yet the next day, when the sun came out, it seemed to open itself like a flower, or as I thought at the time, like a knot, unpicked and unwound. And for several hours we followed this unravelling string of roads and lanes, amazed at every turn at just how pretty it was. Most towns (by no means all) have their more attractive quarters, a sprinkling of timber-framed houses leaning into the streets, peering circumspectively from the past into the present day, yet Colmar seemed to consist almost entirely of buildings such as these. There were of course the odd tower block and less elegant structures, but unlike other towns, where such buildings are in the majority, in Colmar they appeared very much in the minority.

Having walked the streets, sat and sampled the local wine, we drove back towards Luxembourg, visiting the castle of Haut Koenigsbourg on the way. From a distance it does indeed look very impressive, perched on one of the wooded mountains, but up close you realise you’ve been fooled. It makes no apologies for the deception, and tourists, including ourselves still pay the 7 euros and wander through its make-believe rooms, hallways and chambers. It shares something with Colmar, that being the sense that neither would not look out of place in a fairytale. Colmar seems too good to be true, almost contrived, yet walking the streets you feel as if you are in the company of everyone who has ever lived there. They walk with the tourists, the streets they know so well, admiring the houses in which they once lived, telling each other what’s changed since that time. They listen to the stories told by the tour guides, pitting them against their own recollections. But in Haut-Koenigsbourg, we have nothing more than an elaborate film set.

Built on top of the ruins of a genuine castle, the present day structure, constructed around 1905, is neither of the ancient past, or the past of a hundred years ago. It says nothing to us, not because it does not remember the past, but rather because it has none. It’s a mayfly, existing only for the day of your visit. It tells you nothing new, but simply echoes what you know already, expecting nonetheless that you might be impressed. Even the photographs displayed in some of its rooms seem phoney. As we left I was reminded of King Arthur in ‘Monty Python and the Holy Grail’, when after the Camelot song he says to his knights; “On second thoughts, let’s not go to Camelot. It is a silly place”. Our sentiments exactly.

Our visit was quick (at least it afforded spectacular views of the surrounding countryside) and from here we made our way back to Molsheim for dinner. Of course we arrived too early (dinner was at 6.30 and not a minute earlier) and so we enjoyed a drink and waited for the hour to arrive, which soon enough it did.

And on that hour (or demi-heure) people emerged to occupy the empty tables and chairs by which we were surrounded, as if an invisible signal had been given to which we were not privy. I was reminded of one of the children television shows of the late 60s and early 70s – Trumpton, Camberwick Green and Chigley. In Chigley, a whistle is blown at the end of the programme and all the workers in the factory, and all the town’s residents repair to the bandstand to hear the band. Somewhere in Molsheim, the whistle had been blown. We just couldn’t hear it.

Day 9

I received the canvas today and so made a start on priming it.

I also walked my new route and made a list of objects, sounds etc. The full list is as follows:

voices

a siren burst

the sun

engine starts

Leffe

zebra crossing

fat stomach

boarded windows

remnants of posters

black cloak

yellow glasses

sweet smoke

quiet street

red bus

missing letters

pencilled ‘e’

water collected in cobbles

roar of a plane

red lights

cool breeze

weeping willows

a wedding

green mound

old woman

shopping trolley

red man

heart-shaped balloon

Guinness Time

green man

fingers point

pull pull

paper cup

old confetti

cigarette butts

a siren

the sun

a flag hangs

empty racks

wheelie bins

man on a phone

doorbells

dirty water

washing hangs

a broom

plastic bottle

weir

stone tower

scaffold

dead pigeon

sun sparkles

water sounds

lifebuoy

warning!

man with walking stick

drowned bicycle

the stain of a splash

the sound of a coat

scraping tools

a barrier

a signpost

bright sun

people talk

birds twitter

footsteps

CCTV

arrow

ornate gate

traffic cones

roar of bus

music

concrete

shadow

a woman sits

tables and chairs

an empty glass

sun on plastic wrapper

trees

tinted windows

engine ticks over

bus shelter

old people queue

two yellow markers

the sound of a crossing

footsteps

blue plastic bag

graffiti

blue peeling door

sound of a child

green door

carrying shopping

man leaves door

a lamppost peers

old stone walls

plastic bag tumbles

libya libya

lamppost no.6

gutter

half-painted

weeds

hazard lights

painting a window

locks for nothing

purple trousers

a suitcase pulled

footsteps in sand

a taxi

a sapling

arrivals

fruit-boxes

music

soiled blanket

a sink

a mop

checking phone

checking leaflet

bottle top

This evening I read and recorded all the words as an MP3 file. It reminded me to some extent of the extract I published in yesterday’s entry, concerning the reading of the ‘battalion roll-call’, where ‘name after name went unanswered; each silence, another man wounded, missing or dead.’ Tomorrow, armed with this list of words, I will walk the route again, and photograph as much of what is on this original list as possible. Obviously certain things won’t be there any more, certain words on the ‘roll call’ will go ‘unanswered’. The signified objects of other words however will still be in existence, but there will be less, and these missing words will, in a way, act as metaphors for the missing men who did not answer their names in the ‘hollow square.’

I took these words and made them into one paragraph:

voices a siren burst the sun engine starts Leffe zebra crossing fat stomach boarded windows remnants of posters black cloak yellow glasses sweet smoke quiet street red bus missing letters pencilled ‘e’ water collected in cobbles roar of a plane red lights cool breeze weeping willows a wedding green mound old woman shopping trolley red man heart-shaped balloon Guinness Time green man fingers point pull pull paper cup old confetti cigarette butts a siren the sun a flag hangs empty racks wheelie bins man on a phone doorbells dirty water washing hangs a broom plastic bottle weir stone tower scaffold dead pigeon sun sparkles water sounds lifebuoy warning! man with walking stick drowned bicycle the stain of a splash the sound of a coat scraping tools a barrier a signpost bright sun people talk birds twitter footsteps CCTV arrow ornate gate traffic cones roar of bus music concrete shadow a woman sits tables and chairs an empty glass sun on plastic wrapper trees tinted windows engine ticks over bus shelter old people queue two yellow markers the sound of a crossing footsteps blue plastic bag graffiti blue peeling door sound of a child green door carrying shopping man leaves door a lamppost peers old stone walls plastic bag tumbles libya libya lamppost no.6 gutter half-painted weeds hazard lights painting a window locks for nothing purple trousers a suitcase pulled footsteps in sand a taxi a sapling arrivals fruit-boxes music soiled blanket a sink a mop checking phone checking leaflet bottle top

And then to reconstruct the walk, I joined in the gaps with more words drawn from what I remember of the afternoon.

There are voices and then a siren burst cuts through the air, just like the sun. An engine starts and in the window of the pub I see a sign for Leffe beer. I make my way to the zebra crossing and cross the road. A man with a fat stomach walks towards me. Ahead, I see the boarded windows and on them the remnants of posters pasted on and pulled off. A woman in a black cloak wearing yellow glasses walks past me and in her wake I smell the scent of sweet smoke. The quiet street is not normally like this. A red bus pulls in and restores normality. Walking past the boarded up restaurant I see the missing letters of its name. Someone has drawn around them – a pencilled ‘e’ sticks out. To my left is a road with water collected in cobbles and above me I hear the roar of a plane. The red lights stop the traffic and the cool breeze moves the weeping willows in the distance. I see a wedding party move on down the road. To my left is the green mound past which and old woman pushes her shopping trolley. The red man tells me to wait and in the distance I see a heart-shaped balloon bobbing above those who have been to the wedding. A sign on another pub reads Guinness Time and now the red man becomes a green man and I walk over the road. Fingers point, two women look at something, I don’t know what it is. To my left, up some stairs are two doors. The words pull pull invite me up the steps. I carry on walking and pick up a paper cup. On the road are remnants of old confetti and cigarette butts. I hear a siren and the sun makes its presence felt. On top of the tower, a flag hangs – there is no wind. The empty racks wait for bikes and the wheelie bins wait for rubbish. A man on a phone stands ahead of me. I walk past him and see a panel of doorbells. The river is full of dirty water and in a garden, washing hangs and a broom is propped against the wall. In the dirty river a plastic bottle is collected with other muck and litter around the weir above which the stone tower stands, surrounded in part by a scaffold. A dead pigeon lies beneath the bridge and beside it the sun sparkles. The water sounds as it pours through the weir, a lifebuoy is stored on the pavement just in case. There’s a warning! sign. A man with walking stick stands on the bridge and looks down into the water. A drowned bicycle shimmers beneath the water and on the pavement the stain of a splash colours the faded tar. A young boy walks past and the sound of a coat, one made of waterproof material is the only one for a while. Then I hear scraping tools and through a doorway leading to a yard I see a man cleaning his tools. There’s a barrier to my right and up ahead a signpost pointing somewhere. A bright sun lights up the pavement and people talk – three of them. The birds twitter unseen and footsteps ricochet around me. A CCTV signs warns me I’m being watched and a white arrow on a blue background points in another direction. A beautiful, old ornate gate stands incongruously as the traffic cones warn me of the traffic. The roar of bus after bus does not drown the music coming from above me. To my right is the concrete hulk of a building which casts a great shadow over everything. Within it, a woman sits and on the opposite side of the road a number of tables and chairs on which remains an empty glass are positioned. Here the sun on plastic wrapper make a star as trees stand lining the road. Tinted windows forbid the sun and behind me an engine ticks over. There’s a bus shelter and old people queue for their journey home. In the pavement, like gravestones, two yellow markers stand. I hear the sound of a crossing and footsteps cross from one side to the other. Near the steps is a blue plastic bag and on the walls plenty of graffiti. A blue peeling door needs a lick of paint and the sound of a child comes behind me. Up ahead on the right is a green door. A woman carrying shopping walks towards me just as a man leaves door. I notice how a lamppost peers ahead of me, looking at the old stone walls past which a small plastic bag tumbles. Someone has written libya libya on a step. Ahead is lamppost no.6 and from a wall a piece of a gutter protrudes. Two bollards, ones half-painted block the traffic. The weeds grow wherever they can and hazard lights flash on a lorry. A man is painting a window and locks for nothing remain locked around the cycle stands. A boy walks towards me in purple trousers. Another man walks with a suitcase pulled behind him. There are footsteps in sand which is sprinkled on the pavements. There’s a taxi and in its cage, a sapling. The arrivals bag a cab and fruit-boxes are piled high. There’s music and in a small yard a soiled blanket. I walk past an open door and inside I see a sink and a mop. A woman is checking phone and an elderly couple are checking leaflet. There’s a bottle top on the pavement.

The Unknown Soldier

“The Post Office Rifles and the 6th Battalion – ‘the Cast-Iron Sixth – in turn would then pass through their lines to continue the advance to the next objectives on the downward slope of the ridge, the ‘Cough Drop,’ also known as ‘Leicester Square’, and the ‘Starfish Line’. The London Irish and the Poplar and Stepney Rifles were to lead the advance to the west of High Wood, before being succeeded by the 19th and 20th Battalions. ‘The postmen from quiet little hamlets or clerks who had spent their lives hitherto in snug offices, talked about these future regimental mortuaries with the homely names with astonishing calmness…'”

What struck me about this quote from Neil Hanson’s book, was how soldiers used the names of well known and familiar places, to name those places which were not only unfamiliar, but also terrifying, often places of horror and death on a scale which could never be imagined within those more familiar places back home. Trenches were named in a similar fashion: Oxford Circus, Oxford Street, George Street, Broad Street and so on.

“By day, the screams and groans of the wounded and dying had been drowned by the deafening clamour of the battle. At nightfall, though still counterpointed by the rumble of the guns, their pitiful cries and please for help could be hear echoing through the shattered wood…”

This quote reiterates how this war was a war of sounds; how men could be reduced to tears and much worse by sounds; those of the incessant shells or the solitary man crying in a dark wood.

“‘The reading of the battalion roll-call must have broken the hearts of all who heard it – ‘a hollow square of jaded, muddy figures… A strong voice… calls one name after another from a Roll lit by a fluttering candle, shaded by the hand of one of the remaining Sergeant Majors.’ Name after name went unanswered; each silence, another man wounded, missing or dead.'”

This very poignant passage reminded me of some text-based work I did whilst investigating the site of Auschwitz-Birkenau. These text-based pieces started as free-written prose and through a process of increasing the spacing between the letters changed to become squares where the words were reduced to a scattering of letters. As soon as I read the words ‘a hollow square’ I thought at once of those.

The Unknown Soldier

“The Post Office Rifles and the 6th Battalion – ‘the Cast-Iron Sixth – in turn would then pass through their lines to continue the advance to the next objectives on the downward slope of the ridge, the ‘Cough Drop,’ also known as ‘Leicester Square’, and the ‘Starfish Line’. The London Irish and the Poplar and Stepney Rifles were to lead the advance to the west of High Wood, before being succeeded by the 19th and 20th Battalions. ‘The postmen from quiet little hamlets or clerks who had spent their lives hitherto in snug offices, talked about these future regimental mortuaries with the homely names with astonishing calmness…'”

“By day, the screams and groans of the wounded and dying had been drowned by the deafening clamour of the battle. At nightfall, though still counterpointed by the rumble of the guns, their pitiful cries and please for help could be hear echoing through the shattered wood…”

“‘The reading of the battalion roll-call must have broken the hearts of all who heard it – ‘a hollow square of jaded, muddy figures… A strong voice… calls one name after another from a Roll lit by a fluttering candle, shaded by the hand of one of the remaining Sergeant Majors.’ Name after name went unanswered; each silence, another man wounded, missing or dead.'”

Day 7

I decided to do a walk today, one which I would record in single words or very short phrases. I am interested in how we relate to single words and phrases when trying to picture a past experience, particularly of someone else. The following passage from Neil Hanson’s book, ‘The Unknown Soldier,’ gives a very distinct and accurate picture of a scene one of the millions of soldiers witnessed:

“Decayed sandbags, new sandbags, boards, dropped ammunition, empty tins, corrugated iron, a smell of boots and stagnant water and burnt powder and oil and men, the occasional bang of a rifle and the click of a bolt, the occasional crack of a bullet coming over, or the wailing diminuendo of a ricochet. And over everything, the larks… and on the other side, nothing but a mud wall, with a few dandelions against the sky, until you look over the top or through a periscope and then you see the barbed wire and more barbed wire, and then fields with larks in them, and then barbed wire again.”

The simple use of words makes this passage very stark and easy to imagine. We can see it because in our own minds we can easily conjure objects such as sandbags, boards, empty tins and smells such as old boots and stagnant water. My walk around Oxford would therefore be described as a list of words.

The route was as follows:

Gloucester Green

Gloucester Place

George Street

Bulwarks Alley

New Road

Queen Street

St. Ebbe’s

Brewer Street

St. Aldates

Christ Church

Merton Grove

Deadman’s Walk

Rose Lane

High Street

Merton Street

Magpie Lane

High Street

Catte Street

Broad Street

Magdalen Street

Beaumont Street

Worcester Street

George Street

Chain Alley

Gloucester Green

In total the walk was around 4,300 steps and I wrote 631 words, some of which are listed below:

luminous jacket

suitcase

maps

market

bicycles

litter bin

jackets

mirror

coke can

boots

bicycles

taxis

sunshine – dappled

popcorn (smell)

cigarette smoked

sapling

buses

signs

“…do you remember…”

crutches

blue doors

letter box

chewing gum

‘topiaried’ trees

restaurants

cobbles

gutter

spire

bicycle

crunching wheels

cigarette butts

litter

broken glass

telephone

smell of rubbish

yellow lines

drain

graffiti

lampost

cobbles

stone wall

napkin

window

manhole cover

overhanging shrubs

green door

letter box

railings

fence panels

steps

man drinking

mound

sunshine

shadows

pedestrian zone

red telephone box

scaffolding

exhausts

litter bin

bus stop

taxi rank

colours

pinks, reds, blacks

flags

souvenirs

eating

and so on…

On returning the studio, I wrote up all 631 words on a long piece of paper stuck on the wall

What I was struck by, was how they reminded me of the names carved into the walls of the Menin Gate; column after column of words which at first meant nothing, but all of which had their own unique reference. I decided to create a virtual wall of these words which gave them a very different quality:

I had thought of writing all the words as in the extract above, in a prose form, i.e. something like: “a man wears a luminous jacket, another pulls a suitcase. There’s a machine for maps and the market is on. Bicycles are propped against the wall. Nearby is a litter bin…” Adding words however makes it less authentic, and writing them in this style at the time would be far too time consuming. What is interesting however, is how the mind knits the single words together and in a way the prose form is that process – the mind fills in the blanks.

luminous jacket

suitcase

maps

market

bicycles

litter bin

becomes…

“a man wears a luminous jacket, another pulls a suitcase. There’s a machine for maps and the market is on. Bicycles are propped against the wall. Nearby is a litter bin…”

I refer to a previous entry, Reading and Experience in which I quote the following extract from Filip Muller’s, ‘Eyewitness Auschwitz – Three Years in the Gas Chambers.’

“There was utter silence, broken only by the twitterings of the swallows darting back and forth.”

As I wrote: we were not there in Auschwitz at the moment this line describes (the moment before the doomed prisoner speaks up against the camp’s brutal regime), yet we all know silence and have seen and heard swallows. So although we were not there to witness at first hand this terrible event, we can imagine a silence, a particular one we might have felt some place before, and picture a time we saw a swallow fly. We can use fragments of evidence (photographs, documentary footage) to construct a fuller picture, and fill in the gaps with fragments of own experience. When we speak the words of others therefore, those words will form pictures in our own minds drawn from our own experience.

Taking the list above and adding words to turn it into prose, is in a way similar to this filling in the gaps. In this respect, it is worth doing.

I also tried to draw memories of the walk, taking individual words and drawing the corresponding image. It has always interested me, exactly what we see when we remember something. If we could print out a memory, what would it look like? Certainly what we remember is an approximation of what we actually saw, and again, we use words to ‘join the dots’, to fill in the gaps.

I am reminded again of what I read on Memory places:

“It is better to form one’s memory loci in a deserted and solitary place, for crowds of passing people tend to weaken the impression. Therefore the student intent on acquiring a sharp and well defined set of loci will choose one unfrequented building in which to memorise places…”

The image this passage conjures is of a deserted building, one which has seen better days and is perhaps in need of restoration, a shell which needs some gaps filled.

Reading and Experience

“Decayed sandbags, new sandbags, boards, dropped ammunition, empty tins, corrugated iron…”

These words are those of a German soldier – written at the Front just before the Battle of the Somme – and form just a small part of an extract in Neil Hanson’s book, ‘The Unknown Soldier.’ Instantly I read them, they called to mind the remnants dredged from the battlefield which I’d seen in the museum at Hill 62 in Ieper.

On their own, these artefacts are powerful – yet mute – witnesses to the Great War, but when reading a soldier write about them, even listing them as above, they change. They each regain their voice – their signifier, and re-emerge from the shadows.

In my painting ‘Auschwitz-Birkenau Remembered‘ I cut words up into individual letters and scattered them onto the painting, I also wrote directly into the paint itself to show how words failed to articulate the horror of such a place (the written words could barely be read). Another way of looking at this however, is to say that words are able to speak of such horror, but have simply lost their original voice. It then falls to us to speak the words for those who are no longer able to do so, to put them back together.

Subsequent to this, I’ve been thinking about the process of reading, for example an extract from Filip Muller’s powerful testimony, ‘Eyewitness Auschwitz – Three Years in the Gas Chambers,’ in which he describes the horrific murder of a fellow prisoner.

“There was utter silence, broken only by the twitterings of the swallows darting back and forth.”

We were not there in Auschwitz at the moment this line describes (the moment before the doomed prisoner speaks up against the camp’s brutal regime), yet we all know silence and have seen and heard swallows. So although we were not there to witness at first hand this terrible event, we can imagine a silence, a particular one we might have felt some place before, and picture a time we saw a swallow fly. We can use fragments of evidence (photographs, documentary footage) to construct a fuller picture, and fill in the gaps with fragments of own experience. When we speak the words of others therefore, those words will form pictures in our own minds drawn from our own experience.

“As the torrents of machine-gun bullets ripped through the grassy slopes up which the British troops were advancing, the smell of an English summer – fresh cut grass – filled the air. For thousands it would be the last scent they would ever smell.”

This extract, also from Neil Hanson’s book, ‘The Unknown Soldier,’ presents us with an image of slaughter, made all the more terrible (if that were possible) with a reference to the smell of cut grass – one of those smells which invokes in most of us, memories of lazy summer’s days. The two are, obviously, utterly incongruous, yet it somehow makes our task of imagining the horror a little easier. We know the smell of cut grass, and waves of associations and memories are no doubt triggered by the aroma. In the days before the battle, when the soldiers doomed to die waited for the day, they too might have smelled the grassy air and found their way back to times when things were better. It is again the contrast – something which I’ve described before in relation to my visits to Auschwitz-Birkenau and Ieper which makes this passage so heart-breaking.

Finally, I wrote earlier (Imagination and Memory) of how as a child I created a world, made up of fragments of landscapes which I loved, and how as I grew older, I created worlds that were ‘real’ – visions of Oxford as it might have looked centuries earlier. Just as when reading the quote above, I would – as I still do – use documentary evidence to start – images (photographs and drawings) of how the city looked, contemporary writings (such as those of Anthony Wood) – and then fill in the gaps using my own direct experience, in effect, the city as it looks today.

Words

Emptiness

Trauma

Silence

Contrast

Memory

Solitariness

Residue

Postcards

Deckchairs

Forgetting

Objects

Home

Journeys

Walking

Measurements

Space

Past

Two Minutes Silence

Every year, at the 11th hour, on the 11th day of the 11th month, we pause for two minutes and remember all those who died in two world wars and subsequent conflicts. We stand still and in silence, a tradition which, one hopes, will always be respected. Over the last few days, having written about the nature of silence in those places which have witnessed appalling human suffering, I’ve been thinking more about this tradition of silence – not so as to question it (as I’ve said, it is a tradition which must always be recognised and respected) but rather its process; what we think about when we stop and are quiet; what it is we are doing when we remember?

The silence temporarily turns the street, the office or wherever it is we’re standing into a different place; it creates a contrast, against which we might compare our normal everyday environment – that from which we step for two minutes to then rejoin at its end. This act of rejoining is, I believe, as important as the stopping and the silence, for as simple as it is, it’s nevertheless something which millions were unable to do, whether through disability or simply because they never came home at all.

Postcards

I was thinking (given the theme of Residue) about the residues of war, and listed the following sorts of things one might expect to find in the wake of conflict: objects dredged from the battlefield, pieces of shrapnel, bullet casings, shell casings, shoes, photographs, letters, memoirs, bones, clothes, luggage, memories (sights, sounds, smells)… and as I wrote, I thought how important the idea of ‘home’ was, and what a dreadful contrast it must have been to the realities of the often appalling predicaments of those caught up in conflict, whether soldiers or civilians.

Reading various books about World War One, it’s been interesting (and indeed heart-breaking) to read extracts from soldiers’ letters and postcards sent from the trenches, and to read about the packages they received in turn from home. How difficult (as well as comforting) it must have been for them to receive these little pieces of home as they suffered in such unimaginable conditions, and how terrible for parents and relatives to receive the postcards and letters from a loved one after news of their death.

Given that I am exploring the theme of contrast (particularly with regards to the silence of a place following a traumatic event) I thought this was an interesting ‘contrast’ to explore, particularly as Gloucester Green is a place where people are in transit, perhaps travelling away from home.

To change the subject slightly for a moment, one way of identifying with people and events so long ago – for example the Great War – is by identifying with a place (with which we are particularly familiar) as it was at the time, i.e. 1914. I have for a long time been interested in the idea of memory spaces (spaces within the memory of someone either dead or living) and how by accessing these spaces we might gain access to their contemporary thoughts. Under ‘Objects‘ on this site I have written:

“These objects, each through their own unique provenance, allow us, if we use our imaginations, to glimpse people from the pages of history; they, along with tens of thousands of others, once held a place in the minds and memories of men and women long since dead. Now we hold these objects within our minds and memories and as such share a place, a single, common space with those who have long since vanished from the world. To read about the past and those people who made it is one thing, to share this common space with them through the power of objects is quite another.

Objects can be those found in a museum, or buildings contemporary with the time you wish to explore within your imagination; in the case of the Great and the Second World War, it is most of the city (Oxford) as it stands today. As I have already written (on Objects), Aristotle says in relation to systems of memory:

“We should also seek to recover an order of events or impressions which will lead us to the object of our search, for the movements of recollection follow the same order as the original events; and the things that are easiest to remember are those which have an order, like mathematical propositions. But we need a starting-point from which to initiate the effort of recollection.”

This starting point could be anything contemporary with the time we wish to explore. In respect of the Great War, there is a photograph showing men marching to war over Magdalen Bridge and past the Jubilee Fountain which stands near what is now The Plain roundabout. These men are as anonymous to us now, ‘living’ in this photograph, as they are dead, yet the landmarks past which they march are still in existence. That same fountain occupied a place in each of their minds, and so by choosing this as our starting point we might find our way into their thoughts by placing ourselves in their position.

“For remembering really depends upon the potential existence of the stimulating cause… But he must seize hold of the starting point. For this reason some use places for the purpose of recollecting.”

The fountain, in this example, is therefore our ‘stimulating cause’, our ‘starting point’, a place for the ‘purpose of recollecting’. We share in effect a common space with those men who are marching in the photograph and as such we have a starting point from which to ‘initiate the effort of recollection’.

Whilst looking for old prewar photographs of Oxford, I happened upon some old postcards and thought at once how these objects were the perfect metaphor or symbol for our being away from home; a small sliver of our journey away. What we choose to write on the back is largely inconsequential, what is important, is that we have written, that we are remembering those back home.

As I wrote above:

“…how important the idea of ‘home’ was, and what a dreadful contrast it must have been to the realities of their often appalling predicaments.”

Home is an ever-present contrast to that place in which we find ourselves, whenever we travel or make a journey, no matter how long or short, and postcards (now perhaps superseded by texts and emails) are a means by which we remember where it is we come from, by which we close that gap.

Silence

It was after reading a poem by Edmund Blunden that I started to think much more about silence as a space in which to remember. In ‘1916 seen from 1921,’ we get a glimpse of what it was like for Blunden, for a survivor of the Great War, as he looks back at the horrors of the conflict and ahead towards the future.

“…Those ruined houses seared themselves in me,

Passionate I look for their dumb story still,

And the charred stub outspeaks the living tree…”

In my previous entry, ‘Night and Day’ I touched on emptiness as a means by which we (or a place) might best remember an event or events:

“It is better to form one’s memory loci in a deserted and solitary place, for crowds of passing people tend to weaken the impression…”

Emptiness equates of course with silence, and, particularly in the case of the war, and all proceeding wars, silence is the means by which we collectively remember those who lost their lives. It is only now, having visited Auschwitz-Birkenau and Ieper, that I see the two minutes silence as a metaphor for the holes left by those who died; holes made by the absence of sound, the absence of voices. It is not only our voices which are stopped as we remember, but rather those of the dead.

Broken Hayes

Beginning my research into Gloucester Green, I read in the Encyclopaedia of Oxford (Macmillan 1988, ed. Christopher Hibbert) the following entry for Gloucester Green:

“The open area outside the City Wall bounded by Worcester Street, George Street, Gloucester Street and, to the north, by Beaumont Street. There was probably housing here in mediaeval times. After the Black Death in 1348 it became a derelict and decayed area known as Broken Hayes…”

The following is a detail from a map of Oxford made in 1675 by David Loggan. Carfax can be seen near the top left corner, the castle (now much reduced in size) opposite, and in the bottom right-hand corner, Broken Hayes or Hays – the present day Gloucester Green.

In support of those themes which I’ve outlined in my initial proposal I have started to look at contrasts which exists over a period of time within the same space. As I stated on the homepage of my website:

‘How does a place in the present relate to the same place in the past? How do I relate to these places? And how do those who inhabitant the past relate to those of us living today?”

My visits to Auschwitz-Birkenau and more lately Ieper (Ypres) have served to deepen this interest.

The photo above shows Hill 62 in Ieper (Ypres) as it looked during World War 1. Although not entirely clear, one can make out the sandbags and a soldier looking into the camera. Below is a photo of the same area, Sanctuary Wood, which I visited earlier this month.

Standing there in the wood, listening to the birds singing, it was hard to imagine what it must have been like to be there as a soldier in the trenches, deafened by shells and with death and destruction everywhere. In Plato’s ‘Theaetetus‘, Socrates assumes there is a block of wax in all our souls, onto which external stimuli are pressed so their shapes are left behind. This block of wax becomes like our memory and I thought of this as I saw the craters left by the shells. The very earth was the world’s own block of wax, it’s memory, into which the horrors of war had been impressed, never to be forgotten.

As with Auschwitz-Birkenau, the silence was somehow a testament to the scale of death suffered there. Here too, in Sanctuary Wood, the silence seemed to speak at length on the matter. Here and throughout Europe, hundreds of thousands of people, millions even, had simply disappeared.

So, here we have two ‘themes’; the contrast between the same place at two different times, and the disappearance (deaths) of unimaginable numbers of people. This takes me back to the start of this entry; to Broken Hayes.

It is estimated that between 1348 and 1350, between one and two thirds of the population of Europe succumbed to the Black Death. Oxford itself lost around a third to a half of its population and the contrast between the town before and after must have been appalling. In many ways, thinking of this difference, I’m reminded of my experience of standing in Auschwitz-Birkenau and the woods of Hill 62. In both these places, it was the silence which spoke of the terrible traumas suffered there, and in Oxford, on Broken Hayes, I’m sure it was silence which spoke of the town’s own tragedy.

Ieper (Ypres)

The following text can be found on my website under Places. Click here for more on Ieper.

“I should like us to acquire the whole of the ruins of Ypres.. a more sacred place for the British race does not exist in the world.”

Winston Churchill’s quote regarding the fate of the ruined town provides an interesting backdrop to the whole subject of how to remember the past, particularly a past so bound up in the unimaginable violence of The Great War. How should we honour and remember the hundreds of thousands who fought and died in and around this area?

At 8.00pm every evening, The Last Post is played beneath the huge memorial that is the Menin Gate; massive yet dignified, somehow understated yet a great presence in the town. Crowds gather, tributes are laid, and the melancholic refrain coruscates around the gate’s vast interior. Perhaps the crowds and the cameras do correlate with what Siegfried Sassoon said about it being a ‘sight-seers centre’, but there was something particularly moving about the ceremony. Sassoon had seen as first hand the unimaginable horrors of what happened in the fields around Flanders, and just as I stated in my work with Auschwitz-Birkenau, we can never know what it was like to be there. No photographs, no poems, no letters written in the trenches can ever give us the full picture, but we can at least try, and personally, I found the ceremony gave me this chance.

Before we visited the gate, my girlfriend and I made our way to the two cemeteries within the town, The Ramparts Cemetery and the Ypres Reservoir Cemetery. I have seen countless photographs of places like this but nothing prepares you for what it’s like to be standing amidst two thousand immaculate graves, many without names. As I listened to the buglers play The Last Post, I closed my eyes and imagined how every night this same sound rang out from the gate, over the adjacent fields, searching out the bodies of the 54,896 men whose names are recorded on the gate’s walls. The tune is like a calling, a mother’s lament for a lost son. Every night it asks its question, and every night it is met with silence; the silence of the fields once deafened by death and violence.

Rebuilding or otherwise, preserving and restoring are all elements which feature in any tour around Ieper. The Sanctuary Wood museum (Hill 62) is to some controversial in that many believe the trenches preserved there are not actually genuine. Certainly there are aspects of the museum I didn’t particularly like. Personally I believe the trenches are genuine but are perhaps a little over-restored. With a party of school children running around them, there was the sense that this was little more than an adventure playground and not a place which one officer recalled in his dairy of 1917:

“Of the terrible and horrible scenes I have seen in the war, Sanctuary Wood is the worst… Sanctuary Wood in 1914 was a sanctuary, but today, Dante in his wildest imaginings never conceived a like.”

As I’ve said, we can never know what it was really like to be in that Hell on Earth, but I believe the residues of war, the shrapnel, the objects dug from out the ground, along with the craters and the blasted trees are testament enough to the horrors. If the trenches were left and allowed to be reclaimed (although not removed) by nature, I don’t think the impact would be lessened; quite the opposite – it would be enhanced.

Evidence supporting this claim can be found just a couple of miles away on Hill 60. Unlike Hill 62, this place has been left much as it was at the end of war and as such, it has an air of authenticity about it which one doesn’t quite get with the trenches of Hill 62 (I should state here that there is no doubt about the provenance of Sanctuary Wood itself, the craters, the shot trees and recovered objects). The craters of Hill 60, the undulating and wholly unnatural shape of the landscape, now grown over with grass are enough to inspire the imagination to thoughts of what happened there 90 years ago. It is perhaps this dramatic contrast between now and then which facilitates this: the grass, the trees, the birds; (the birds which inspired some of the most poignant words to come from out the trenches). That and the knowledge that many men from both sides still lay buried beneath the ground. I was also reminded as I walked over the grass, of the parks one might find back home – a place for people to relax, for children to play in – a place to forget all your worries. This contrast again served to remind me of the horror and futility of war.