New Work 2

New Work

Past and Present Postcard

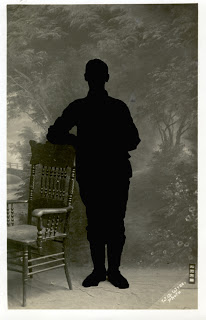

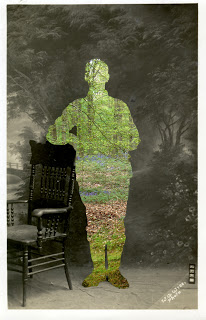

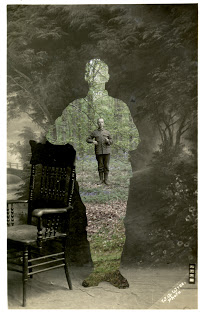

The image below is the last in a series I’ve made using both an original World War One postcard and a photograph I took in Verdun. All are works in progress.

I’ve been fascinated with the backdrops in some of these postcards for quite some time now and have been looking at ways of using them in works relating to the Great War and, in particular, the issue of empathy.

The original postcard is of course in black and white (with a greenish tint) and shows a soldier about to head to the Front, standing, leaning on a chair.

Behind him is an idealised image – an idyllic, invented landscape, a far cry from what he was, perhaps, about to encounter, but close in some respects to what we find on battlefields today; where there were trenches, arms, barbed wire and bodies, there are now trees. And amidst the trees, incongruous concrete Pill Boxes stand and watch as the seasons come and go. Everything is slowly reclaimed. The trees in the image at the top of the blog spill to reclaim the past – the interior of the studio – through the gap left by the missing soldier.

I have placed the solider back beyond the gap left by the vague shape of his own body, to remind us that people like the soldiers we see in all these postcards, were once like those of us who have visited the battlefields. They too would have known what it was to stand in a wood. To listen to the wind blowing through the branches.

To stand and do just that, is one way to remember them.

Work in Progress

New Work (WW1) 2

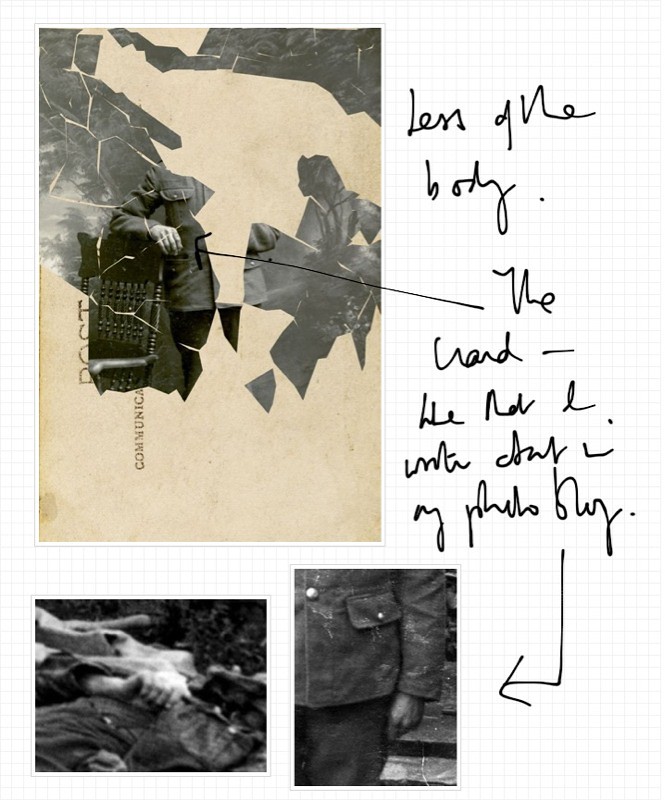

Looking again at the latest work I’ve done (see previous entry), I decided to make the image of the man less clear. Taking away his face, I found my attention drawn to his hand which in turn reminded me of some work I’d done on hands with regards photographs from World War I.

New Work (WW1)

Again using the idea of the lines/patterns of trenches, I’ve reworked an earlier idea using an old World War One postcard.

Two Soldiers

I was once given a collection of 200 World War I postcards featuring portraits of soldiers and have always wanted to trace some of those featured. Through research on the National Archives website and through deciphering rather bad handwriting I discovered that the man immediately below is one Walter Henry Chevalier who served in the Army Service Corps and Northumberland Fusiliers. I think, if my research is correct, that he survived the war, dying in 1962 aged 64.

Below, another World War I soldier and another survivor. The rather splendid surname ‘Dangerfield’ is written on the back and having searched for him and got over 100 Dangerfields I had a closer look at the image. The spurs and the crop suggest of course something to do with horses and the cap badge as far as I can see is that of the Royal Horse Artillery. Having refined my search, I found Edward Paul Dangerfield, Second Lieutenant in the Royal Horse Artillery. Again, if my research is correct, he survived the war and died in 1978.

New Marston War Memorial Names

At the bottom of my street is a War Memorial such as you find in most towns and villages throughout the country. I’ve walked past the memorial many, many times and while I’ve often thought of those who died in both World Wars, I’d never before read its list of people. Therefore, this week I did just that and have spent time researching where they died and where they’re now buried.

A couple of details at once stood out : A G Akers, the first on the list, lived in my road and died of wounds on the last day of the war; 11th November 1918. Arthur Gerald Harley was killed in action, aged 21 on 1st July 1916 – the infamous first day of the Battle of the Somme.

I will endeavour to find out as much as I can about some of those who are commemorated on this memorial, in the meantime the following list is what I’ve so far discovered:

Remembrance

During this week of Remembrance, a few days after the 90th anniversary of the end of the First World War, I’ve been thinking about how it is that an event which happened almost a century ago still holds such a powerful draw on our consciences today. What is it that makes the Great War seem anything but distant when events which proceeded it only by a few years seem twice as far in the past?

In the last couple of days I’ve been continuing my research into my great-great-uncle Jonah Rogers, who was killed on the 8th May 1915 at the Battle of Frezenberg Ridge.

I have now been able to locate the positions he held as part of the 2nd Monmouthshire Battalion, on the day of the battle, being as they were part of the 12th Brigade in the 4th Division (thanks to Martyn Gibson and David Nicholas for their help with this).

In a ‘History of the 2nd Battalion Monmouthshire Regiment,’ compiled by Captain G.A. Brett, D.S.O., M.C., I read the following account of the battle in which Jonah lost his life.

“By the 8th May the British had withdrawn from the most advanced points of the Ypres salient, and the Germans, striving to obliterate the salient completely, made further determined efforts to gain ground. Desperate fighting ensued, the six days, 8th to 13th May, of the Battle of Frezenberg Ridge, giving many anxious hours to British commanders. When the storm broke the Battalion was on the right of the brigade still holding Mouse Trap Farm…”

Looking at a diagram of the Battle of Frezenberg Ridge, one can see clearly where the Battalion would have been stationed; to the left of the 84th Brigade at Mouse Trap Farm.

The more I ‘get to know’ Jonah, the more the war as an historic event, changes. Whereas before I could only know it as a thing in its own right, an homogenous mass observed from a distance, like a planet in the night sky, now, with a shift in focus, I see Jonah first, and then, through him the war. The telescope becomes in effect, a microscope, with Jonah the lens through which the war, in all its millions of parts, is magnified.

I do not know the exact details of how Jonah died. Given the ferocity of the artillery bombardment and the use prior to this of poison gas, there are any number of possibilities. And although knowing the nature of his death would add to the emotional weight of his story, it is the possibility of pinning down the location of his death which makes more of an impact upon me. It serves to make him – and the war – more vivid, more real. By locating him in the places where he lived and where he died, and by alternating one’s thoughts between the two, one can imagine too his loved ones, shifting their thoughts between memories of him at home and thoughts of him at war. And in that space between – a kind of No Man’s Land – one can locate their fears and their prayers. The same can be said for Jonah, who no doubt during the months he was at the Front, staring across at the enemy, thought a great deal of the place in which he lived.

For his family, left behind in Hafodyrynys, the war could only be imagined but would permeate everything they did. Whatever they did, however mundane, there would be the war. Even in the landscape, in its shape, its colour, its sounds, the war would be contained but never spilled beyond the outlines. And in these shapes and spaces, their hopes and fears would vie against each other.

Perhaps the fact I can share at least some of this space, in the movement of my own thoughts between the place he lived and the place he died, helps explain the reason why, although I know what happened to him, and where and when it happened, I still feel, when reading about the war prior to May 1915, a sense of concern for his wellbeing. If I read any account of the war after the day he died, every word is permeated with his absence. That is not to say I mourn as such (as his immediate family would of course have mourned) but I do sense his absence, I do sense the anxiety of his separation (in the end, eternal separation) from home.

Without a known grave, this separation – his death – must have been all the more difficult for his family. On the gravestone of his older brother, William, who died aged 10 in 1897, the following inscription has been added:

Also of Pte. Jonah Rogers, 2nd Mon Regt. Son of the above Killed in Action in France, May 8th 1915.

Jonah has no known grave, save that within the minds of those of us who remember him. Perhaps then, my concern is for the wellbeing of his memory?

We must all as individuals continue to remember. We must remember that the millions who died in the slaughter, were not an anonymous mass brought into play by History (just as we are not an anonymous mass brought together to remember) but young individuals, taken from their homes and loved ones; individuals to whom we are all related. A million British and Commonwealth soldiers lost their lives in the War. A million graves, known and unknown lay in the fields of Flanders and France. Back home, a million holes, will only ever be filled with the thoughts of those who come after them. Thoughts that pass with our passing. Holes to be filled again by successive generations.

The Unknown Soldier

Extract from Neil Hanson’s book, ‘The Unknown Soldier,’ concerning the infamous Battle of the Somme.

‘The next day, the regiment began the long march to the Front. In the heat of early summer, nature had made attempts to reclaim the violated ground and a deceptive air of somnolence lay on the landscape. “The fields over which the scythe has not passed for years are a mass of wild flowers. They bathe the trenches in a hot stream of scent,” “smelling to heaven like incense in the sun.” “Brimstone butterflies and chalk-blues flutter above the dugouts and settle on the green ooze of the shell holes.” “Then a bare field strewn with barbed wire, rusted to a sort of Titian red – out of which a hare came just now and sat up with fear in his eyes and the sun shining red through his ears. Then the trench… piled earth with groundsel and great flaming dandelions and chickweed and pimpernels running riot over it. Decayed sandbags, new sandbags, boards, dropped ammunition, empty tins, corrugated iron, a smell of boots and stagnant water and burnt powder and oil and men, the occasional bang of a rifle and the click of a bolt, the occasional crack of a bullet coming over, or the wailing diminuendo of a ricochet. And over everything, the larks… and on the other side, nothing but a mud wall, with a few dandelions against the sky, until you look over the top or through a periscope and then you see the barbed wire and more barbed wire, and then fields with larks in them, and then barbed wire again.”

As the torrents of machine-gun bullets ripped through the grassy slopes up which the British troops were advancing, the smell of an English summer – fresh cut grass – filled the air. For thousands it would be the last scent they would ever smell.’