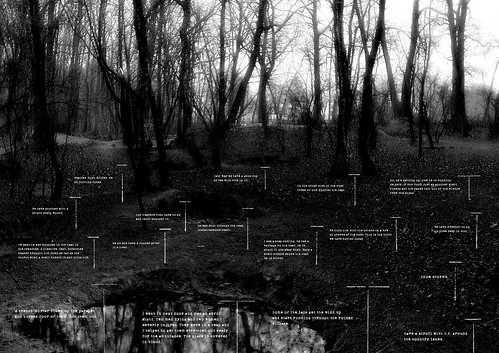

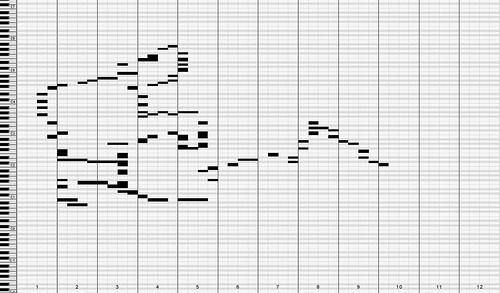

Today, on a walk around Oxford, I completed my first text map which I began in Ampney Crucis about a month ago. Below is both the map and an image of the walks as recorded on my GPS (and then ‘arranged’ in Photoshop).

Map Work

I’ve almost completed my map of observations made during a number of walks over the past few weeks and am now looking to see how I can progress this line of work.

The paper shown above has started to soften, from being carried for so long in my pocket and being held in my hand as I walk. It’s started to feel almost like material. I like the way too that it’s acquired those tell-take signs of wear and tear; dog-eared corners, rips and holes and creases.

On the reverse, you can see the selotape used to keep it all together, indeed there is something about this side which I really like.

I like the idea of these pieces becoming maps of individuals rather than just a place, while at the same time representing people as places – or at least the product of places. I like the idea of them becoming patterns, such as clothing patterns, again giving a sense of the individual.

Another part of this process has been the recording of my walks using GPS. I have, for this work, been putting them all together in one image.

In our minds, when we think about our own past journeys, there is little sense of space, i.e. the physical space between the places in which we made those journeys. Everything is heaped together. Time, like physical space is also similarly compressed. All the walks I’ve made for this work therefore are heaped one on top of the other, with little regard to their geography or temporality. The past with which I seek to identify is also like this. Geography and time are compressed. Everything is fragmentary.

In any given place – for example, Oxford – we can, as we walk down an ancient road, follow the (fragmentary) course of a life lived centuries ago. But walking down another road, we turn and pick up the fragment of another life. And so on and so on.

It is this fragmentary nature of past time, and its compression of time and space, which makes it sometimes hard of for us to empathise with anonymous individuals who lived in the distant past. To make sense of the fragments, we need to see them in the context of the present – in the nowness of the present. By doing this, we can begin to unpick these matted strands of time and space.

History is the attempt to make sense of the fragments left behind by time – to construct a narrative of events with a beginning and an end. It has a point A and a point B, between which the narrative weaves a path, much like a script, novel or score. What I’m interested in however are those fragments, not as parts of a narrative progression, but as fragments of a moment in time – a moment which was once now. As I’ve written before:

Access to the past therefore comes… through the careful observation of a part in which the whole can be observed. As Henri Bortoft writes in The Wholeness of Nature – Goethe’s Way of Seeing; ‘…thus the whole emerges simultaneously with the accumulation of the parts, not because it is the sum of the parts, but because it is immanent within them’.

Consider the span of an hour, and imagine a city over the course of that hour with everything that would happen throughout that period of time; history with its refined narrative thread, is rather like a line – a route – drawn through a map of that place. The line delineates space (in that it starts then ends elsewhere) but we know nothing of what happens around it – the mundane, everyday things which make the present – now – what it is. In my walks I capture moments, observations of mundane things happening around me as I walk.

For example:

A man talks holding his hat

A flag flies, fluttering in the growing wind

The next bus is due

A car beeps

Amber, red, the signal beeps

The brakes hiss on a bus

One could argue that these observations still represent a linear sequence rather than being fragments of a single moment in time. However, reading them, one does get a sense of the nowness of the past. The route as drawn by the GPS represents the narrative thread (history) whereas the text represents the individual moments from which the narrative is constructed.

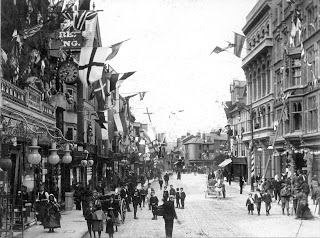

Imagine if someone had done the same in 1897 at the time of last Diamond Jubilee.

We get a sense of the nowness of a past time from images such as that above, but as Roland Bathes states, time in photographs is engorged. It doesn’t move. With the work I’ve made above however, the immediacy of a past time is captured, but, unlike photographs, is fluid. And it is this fluidity which is crucial to an empathetic engagement with the past. For the nowness of the present isn’t static, but rather flows within us and around us.

The following text from Robert Macfarlane’s ‘The Wild Places,’ interested me a great deal in light of what I’ve written:

“Much of what we know of the life of the monks of Enlli and places like it, is inferred from the rich literature which they left behind. Their poems speak eloquently of a passionate and precise relationship with nature, and of the blend of receptivity and detachment which characterised their interactions with it. Some of the poems read like jotted lists, or field-notes: ‘Swarms of bees, beetles, soft music of the world, a gentle humming; brent geese, barnacle geese, shortly before All Hallows, music of the dark wild torrent.'”

Heavy Water Sleep (Paintings) III

I worked again tonight on the studies for Heavy Water Sleep, working in landscape elements such as trees and sky. The original text from which the words are taken, ‘Pilgrims of the Wild’ by Grey Owl, is set chiefly in the forests of Canada. And in the ‘secondary text’ which inspired the work in the first place, ‘The Diaries of Adam Czerniakow’ there is a moving passage in which, following a visit outside the Warsaw Ghetto to the woods of Otwock, he writes simply, ‘… the air, the woods, breathing.’ Trees then seem integral to the work and have indeed been a recurring them in much of my work, particularly work to do with the Holocaust and World War I.

I wanted then to use trees in these works and found myself using a stylised form which I’d scribbled one day in my notebook based on lines you find in Family Tree diagrams.

This symbolic tree was in part inspired by some work I did on the First World War in which I used the dividing lines on the backs of original wartime postcards to symbolise the bond between the anonymous individuals who died in the war and their families back at home. These ‘T’ shaped divides reminded me of photographs in which hastily dug graves were marked on battlefields with crude crucifixes. I therefore created landscapes (based on my visits to battlefield sites on what had been the Front) and used these T-shapes to represent graves.

From these T-shapes I derived the forms for the trees below.

The link between them and the Ts above is an obvious one – even more so when one considers the original inspiration for this work.

Heavy Water Sleep (Paintings) II

I worked again last night on the ‘Heavy Water Sleep’ paintings, continuing to concentrate on the texture. For the first board below I used a white acrylic paint mixed with an acrylic modelling paste.

The words are too chaotic in this one and the paint has dried very matt. I could add some gloss medium but it would make much more sense to use oil paint which I will for the final versions. I will add another layer to the painting above later.

Having completed this painting I worked again on the one I did yesterday.

I like how the words are slightly more obscured now and much prefer their more ordered placement. The next thing I want to try is keeping the lines of the pages together rather than placing them in a random fashion.

Heavy Water Sleep (Paintings)

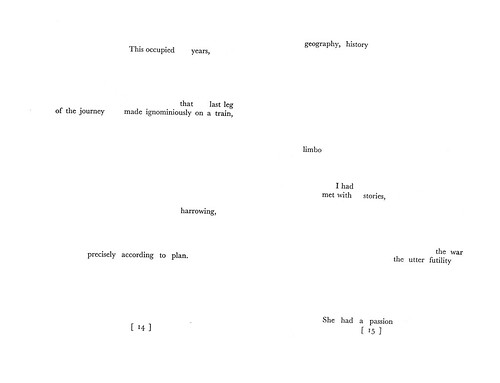

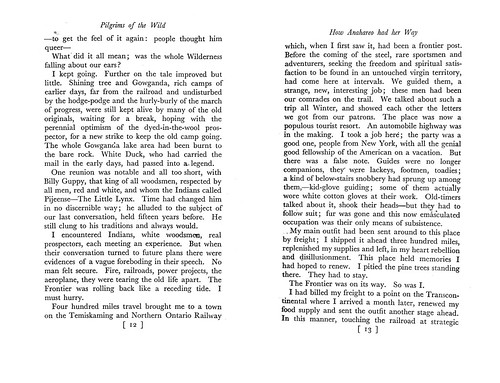

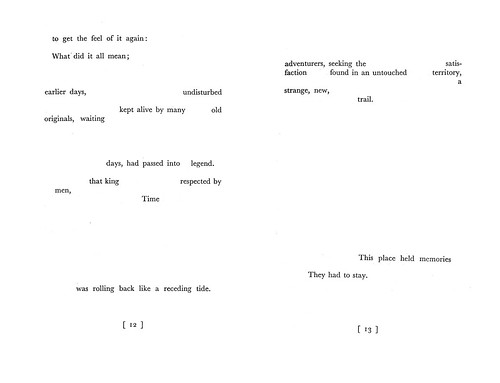

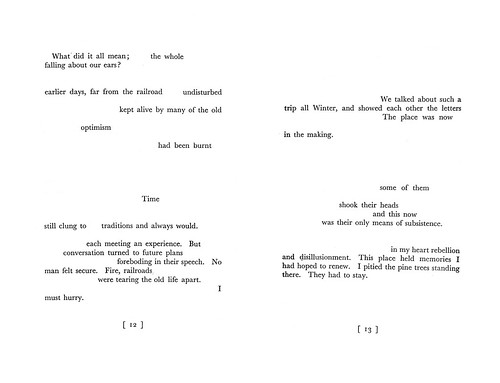

I’ve started work on a new series of paintings based on the Heavy Water Sleep work I’ve been doing over the past few years. The idea is to create a series of paintings based on the idea of the words being a trail in a landscape (in turn derived from the idea that the book is a kind of map, leading me through the landscape of the past). The words from each page will be cut out with most painted over either wholly or in part. The words which make up the ‘poem’ of each page will be left, as per the image below.

The above sketch shows how the words might be placed.

What I realised after completing this sketch is how important it is to create a sense of depth in the work. At the moment the words are raised upon the surface, whereas they need to appear ‘sunk’ into the paint layer like footprints in the snow. Furthermore, the picture plane needs to be much bigger to give a greater sense of space – of wilderness; after all, this work represents the idea of the past as a place.

I shall continue – fo the time being – working on this scale in order to get the textures right, then progress to a larger canvas.

I suppose the ‘feeling’ I want to achieve with these paintings is that of the lone traveller, following in the footsteps of someone long since gone, and the one landscape painter who comes to mind is Caspar David Friedrich, two of whose pictures are reproduced below:

Of course I’m not aspiring to create something that looks like these paintings, but something which instills within the viewer the same sense of space, solitude and wilderness – not forgetting a sense of time’s inevitable passing.

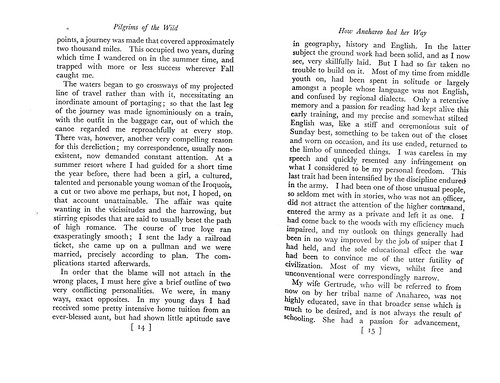

Heavy Water Sleep: Pages 14 & 15

Heavy Water Sleep: Pages 12 & 13

Heavy Water Sleep: Page 11

Heavy Water Sleep: Pages 10 & 11

Heavy Water Sleep: Pages 8 & 9

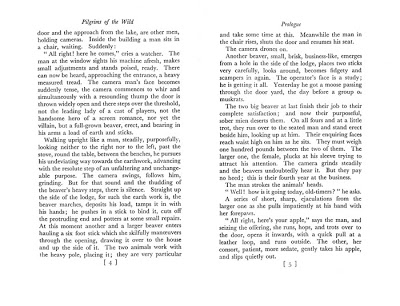

Heavy Water Sleep: Pages 6 & 7

Connections

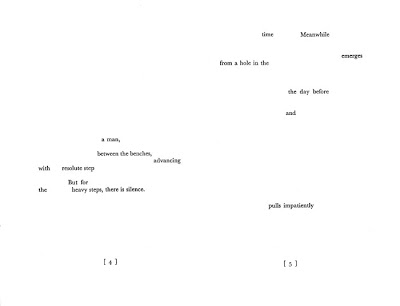

Heavy Water Sleep: Pages 4 & 5

Heavy Water Sleep (Combined)

Heavy Water Sleep

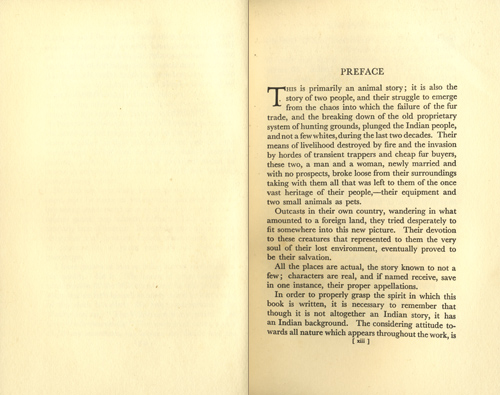

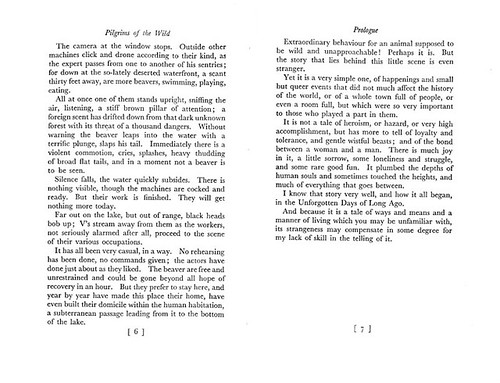

Continuing from what I was discussing yesterday (see Humument), I decided to make a start on my own ‘Humument’ by reading the first page of Pilgrms of the Wild by Grey Owl, using the text to describe something about the moment in which I was reading it. Given the snow and the freezing conditions outside, I was surprised at what I came up with, and very pleased with the result. The image below shows the original pages with my amended version below:

It goes to show how this technique can lead to unexpected, and in this case, rather beautiful results. I would never have thought before of describing snow as ‘water sleep’, but as my eyes scanned the page, the combination of words lept out at me.

My plan is to rework a page a day – not necessarily every day – and to rework the same pages with the Diary of Adam Czerniakow in mind.

A Humument

In January this year, I used words from two seemingly unrelated books to create an installation in Shotover Country Park as part of Holocaust Memorial Day. The piece was called The Woods, Breathing, the title coming from an entry in the diary of Adam Czerniakow, who was ‘mayor’ of the Warsaw Ghetto up until his death in 1942.

In his diary, on January 19th 1940, Czerniakow describes a book he’d read, of which, he wrote: ‘The forest, little wild animals – a veritable Eden.’ The book was Pilgrims of the Wild by Grey Owl, and his comment is especially poignant given the horrors of the time in which he was living. It’s as if in the book, he found the freedom he craved, freedom which vanished as soon as the book was closed. The previous year, a few months after the start of the Nazi Occupation, he wrote how he was ‘constantly envying all the heroes of my novels because they lived in different times.’ There is a sense then, when he describes Pilgrims of the Wild that he is also envying the author, Grey Owl.

I’ve always seen Grey Owl’s book as a map, as in many respects all books are, maps through fictional landscapes, half conjured up in the minds of the author and his or her readers. Having read Czerniakow’s diary, reading Pilgrims of the Wild bought me closer, not only to him but to the time in which he was living, as if reading the book was a shared experience; as if we were walking through the same landscape, emerging at the end in very different places. That is not to say of course that reading the book enabled me to understand what it was like to live in those terrible times – nothing can ever do that. But by reading the words he would have read, it was as if I was following in his footsteps.

Looking up from the page, gazing out the window at the sky made me consider the present, the moment in time in which I was living. The sky was that of the book’s landscape, and that which Czerniakow would have seen outside his own window. We must remember, although it seems quite obvious, that the past too was once the present. By understanding this, we can begin to find indviduals lost to the pages of history. We don’t know what it’s like to experience the horrors of Nazi persecution, but reading the book beomes a shared experience, both mentally and kinaesthetically. It is an everyday activity, which opens up a crack through which we can glimpse the past.

Tom Phillips’ ‘treated Victorian novel’ – A Humument – (a page from which is pictured above) has always interested me; the technique of taking a text and changing it to make something entirely new is appealing for a number of different reasons. Every conversation we have, letter we write or note we take borrows from conversations, letters and notes spoken and written over the course of centuries (depending of course on how long the language has been used). Similarly the way we move, whether walking, sitting, standing or reading, borrows from the ways people have moved, again over the course of many hundreds, if not thousands of years. For me, Tom Phillip’s technique as used in The Humument articulates this. It’s as if we’re in the same landscape created by the original work (A Human Document by W.H. Mallock, first published in 1892) and yet are making our way through it in an entirely different way, as if the words are breadcrumbs on a trail, most of which have long since vanished.

As we walk down streets today, across parks, or through woods, we find ourselves within the same place as those who walked there a hundred, two hundred, maybe three hundred years before. We use the same words, we move the same way, but find ourselves interpretating the place quite differently. But it is the same place.

I want to useTom Phillips’ technique and create a new work from Pilgrims of the Wild, a page from which can be seen below; a work that articulates both my time of reading the book and that of Czerniakow’s.

Text Rain

The following image is taken from Tom Phillips’ book, Postcard Century. I was reminded on looking at the image of a piece I made called Dreamcatcher and in particular a photograph I took of work in progress.

Dark Tourism Conference II

Having thought about the ideas raised after my visit to St. John’s College, I decided to try the idea out in my studio space at Brookes. I began by copying the entry on St. John’s College from the Encyclopaedia of Oxford which, using a water-based marker I then wrote out (in part) onto one of the windows. The windows are not the right shape for the project but I got a good idea of how it would look nevertheless.

Having used the text of the history of St. John’s I decided to write on another window, all that I could see as I looked through the glass, and, having done this, I considered the significance of the two.

The text delineates the surface of the glass and so defines it more readily as a barrier; the text itself is not a physical barrier but rather a conscious one. One is able to shift one’s focus from one to the other but can never see them at the same time – at least not clearly. With regards the text describing the scene beyond the window I found that this created an interesting, temporal exchange. Looking through the text one can see the world as it is ‘now’, whereas when reading the text one can only see the world (albeit in words) as it was. You have to read/view one or the other – you can’t do both.

Reading the text traps the viewer for a moment in the past and obscures the reality of the world. It follows therefore that seeing the world as it is outside hides the past. Reading the text describing the scene outside as the text was written, one can flit between past and present but can see by doing so how some things remain the same. A building for example described in the text might well be the same as when viewed through the glass, whereas someone who was walking beyond the glass when the text was written will exist in words but will not be visible to the viewer when looking (reading) between lines. Of course it might be that words used to describe a person in a somewhat vague fashion in the text may be applicable to someone beyond the glass when the viewer’s focus is shifted; for me, this is a good way to represent the continuity of life and also acts as a warning that the past can always repeat itself.

How does this work resolve with the issue of Dark Tourism? Let’s assume we are in Auschwitz-Birkenau. As tourists we are exposed to a place of trauma; we constantly flit between the past (that of which we’ve read in testimonies or seen in films and photographs) and the present (the reality of the world around us). Often we cannot make a connection between the two. We may well have read about one million dead but standing where we stand in the present, we simply cannot imagine it. However, when we do see something that fits the ‘text’ and the world around us, when we find a correlation (such as the gate tower), the past with all its trauma is brought into the present and vice-versa; there is in effect an exchange. But of course we are always safe behind the barrier; the barbed-wire-text fence doesn’t keep us in, but keeps the past at bay.

So why do we visit places of trauma? Perhaps it’s because we can always leave, we can move between past and present, yet know that we can always go home. Perhaps that’s why we go to places such as Auschwitz; because we know we can leave – leave with our existence all the brighter because of it, framed by the shadow of the past.

In the end, words (whether describing the experience of a tourist or a victim) can only take us so far. As Elie Wiesel wrote: ‘I would bring the viewer closer to the gate but not inside, because he can’t go inside, but that’s close enough.’ We can walk up to the ‘barbed-wire’ (text) fence, we can see the wires (read the text) and see through them, but we can never go any closer – not would we want to; that is, as Wiesel says, ‘close enough.’

Dark Tourism Conference

This morning I went down to St. John’s college to view a room in which I’ve proposed to exhibit work during a conference to be held there in April. The conference is titled ‘Travel and Trauma: Suffering and the Journey’ with a sub-heading; ‘A Writing Journeys and Places Interdisciplinary Colloquium,’ and therefore I wanted to show something which would fit in with this theme. Even though much of the work on my MA has already dealt with this subject and would be entirely appropriate for this event, I have in mind to do something new. And so, I went to view the space to see what possibilities it might afford me.

The space itself is a room in a modern block and what I noticed right away was that there was a lot of glass with, and as a result, a good view of the outside. I asked if the outside might be used and there seemed to be no objections to this. However, the more I thought about the space, and the more I thought about the conference title, the more I saw myself writing – creating a work with text. I thought of some of the work I’d done in the past, and the painting I made after my visit to Auschwitz gave me an idea.

The text written across the painting and resembling wire immediately made me think of writing in a similar style across the large windows in the room (perhaps with a black chinagraph pencil). But what would I write? Whatever it was would have to be relevant to the space and the idea of tourism and after thinking for a while I considered again the view beyond the window – the reality of what was on the other side of the glass. I thought of writing a history of St. John’s college but then considered instead, the idea of writing a description of what was actually there outside, framed by the window at which those reading the text would be standing; reading and yet blind to the reality of what was in front of them.

So what would this mean: people reading the text describing the reality of what was there ahead of them, blind to that reality because of the text/wire behind which they are held? For me it signifies the impossibility of getting near to the reality of an event through writing/reading about and expriencing a place, but saying that, it wouldn’t be a work suggesting the futility of such experiences – far from it – but it would hopefully raise questions about our role as tourists.

Words

Emptiness

Trauma

Silence

Contrast

Memory

Solitariness

Residue

Postcards

Deckchairs

Forgetting

Objects

Home

Journeys

Walking

Measurements

Space

Past

![14-15 [17.06.11]](https://farm4.static.flickr.com/3059/5841597001_471957f641.jpg)

![08-09 [29-12-2010]](https://farm6.static.flickr.com/5247/5303331149_0a89793a3e.jpg)

![06/07 - Version 2 [22-12-2010]](https://farm6.static.flickr.com/5201/5283413870_e12da0c9dc.jpg)

![06/07 - Version 2 [22-12-2010]](https://farm6.static.flickr.com/5289/5282813285_dca9eda7f1.jpg)

![04/05 - Version 2 [21-12-2010]](https://farm6.static.flickr.com/5243/5280921725_3d72b17df6.jpg)