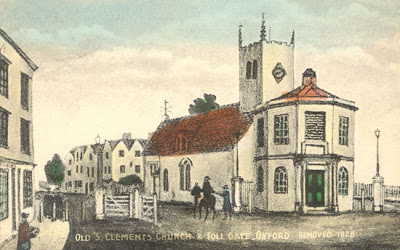

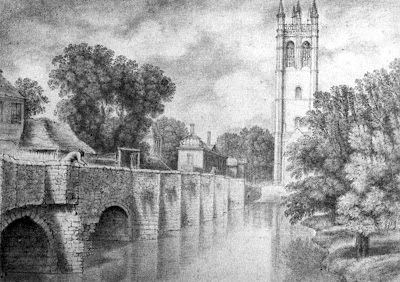

The old church of St. Clement, built around 1122 is a principal character in our story. It was described by the antiquary Thomas Hearne as “a very pretty little church,” but unable to serve the growing population of the parish, it was demolished in 1828 and a new church built on Hacklingcroft Meadow in Marston. The church’s three bells (one of which is the oldest bell in Oxford, dating to the 13th century) were taken to the new building. The church’s graveyard remained until 1950, when it too disappeared with the construction of The Plain roundabout.

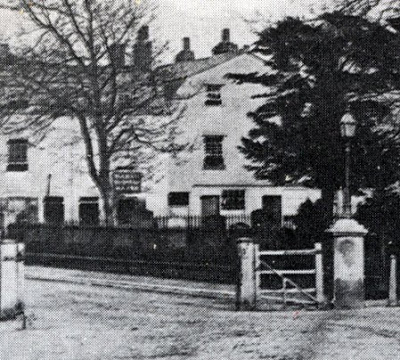

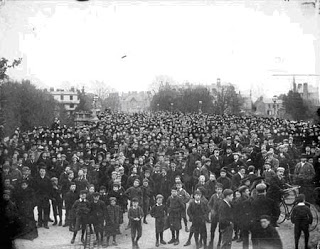

The toll house in front of the tower remained until the construction of the Victoria Fountain in 1899. The photograph below, taken in 1868, shows the old toll house and the churchyard behind.

Looking closely one can see the gravestones…

…and the ghosts of those who walked too fast.

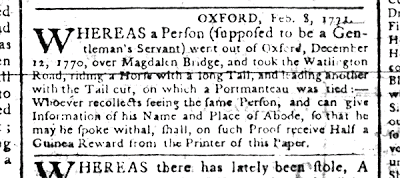

It’s interesting to compare the image above with the text of the newspaper notice. Both contain the likeness of a man on the same stretch of road, and yet that created 100 years earlier with words is, somehow, all the more clear. With the image above, we feel the same sensation as when we look at other very old photographs; a kind of vertigo which links – through a ‘carnal light’ – two poles of simultaneous existence and non-existence. We look at the image of a man in a time when he doesn’t exist, while he looks back from a time when we have yet to be born. Here we both are, and aren’t at the same time. The light, captured in the image, is, like an “umbilical cord” which as Sontag says, “links the body of the photographed thing to my gaze – light though impalpable, is here a carnal medium, a skin I share with anyone who has been photographed.”

In truth, we share this skin with anyone who’s ever been and it’s through our bodies that we identify with those who’ve gone before us. With the text, our sense of the man comes not only through that which the words describe, but through the questions it asks and leaves unanswered. Furthermore, there is a sense of movement in the writing. We not only get a snapshot, but a full few minutes of this anonymous man’s life – a seemingly insignificant moment which serves, ironically, to make him all the more clear. It’s as if the blurs in the photograph above, caused by the long exposure and the movement of those in view, were instead a piece of film, one in which we don’t see a ghost, but a living, breathing individual.

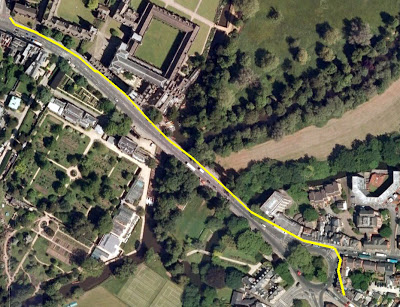

This sense of movement is of course something we also share, and it’s this kinaesthetic aspect of the text which seems to count the man – whose more than likely been dead for more than two centuries – among us. Because I’ve walked and experienced the insignificant, ‘everydayness’ of moments on the bridge, I seem to know him better than, for example, I do the man who stands against the toll house in the photograph. The man and the toll house have both disappeared. But the line of movement, the narrative line, and therefore the stranger of our tale, persists to this day.