Another triptych comprising photographs taken on Sunday at Shotover.

Trees Triptych

A triptych comprising photographs taken at Shotover on Sunday.

A Walk in Shotover Wood

On what was a beautiful Autumn day, I took a walk to Shotover wood to take some photos of trees. I’ve always loved Shotover, both for its place in my past and that of my family, and its own history, being as it once was the main road to London (the mounting steps at the top and bottom of the hill are particularly interesting). The following images are a few of the photographs I took.

Trees and Other Projects

I have been photographing the same trees – shown above – for almost 18 months now, and what started as a simple photographic record of a particular set of trees has since morphed into a project which shares certain aspects with other lines of research. I was drawn to them initially by their shape and proportions; by the fact that they reminded me of an Isaac Levitan painting, such as that below.

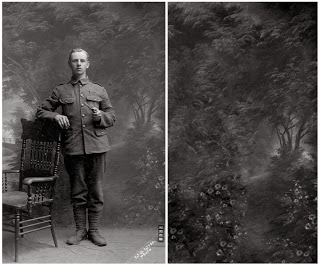

Since then, as my personal circumstances have changed through separation, the trees have come to signify something else. Being separated from my children for much of the week, there’s a connection between this anxiety and that which is present in the postcards of World War I servicemen, photographed in studios before they left for the Front, often against a painted backdrop of trees.

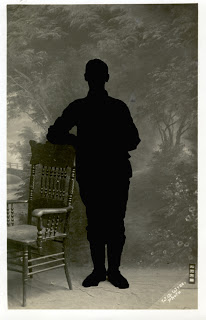

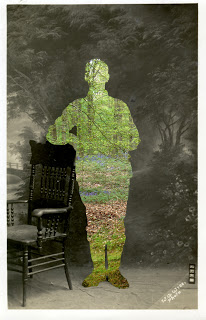

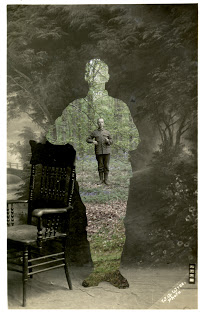

I worked on this theme previously, working with postcards such as that above and creating montages that used photographs I’d taken of trees at one-time battlefields such as the Somme and Verdun.

The Lawn and the Woods

I remember as a small boy how my Nana would on occasion take me and my older brother to where she worked as a Housekeeper. The house was – at far as I recall – a big, white, Modernist building with a large well-kept lawn at the rear. But what I remember most was the wood which stood at the edge of the garden. I can see it now – that contrast between the manicured lawn and the wild dark of the trees, and with the work that I’ve been doing on gardens, trees and contrasts, this particular memory has suddenly sprung to life.

Lamenting Trees

‘Ghastly by day, ghostly by night, the rottenest place on the Somme’. Such was how soldiers described High Wood, one of the many that peppered the battlefields of Flanders and France. Woods in name only, these once dense places were quickly reduced to matchwood. One officer, writing of Sanctuary Wood near Ypres, declared that: ‘Dante in his wildest imaginings never conceived the like.’

We, in our wildest imaginations can not conceive the like. So how can we remember and empathise with those who for whom it was real? Historian Paul Fussell provides a starting point:

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

I aim therefore to create a series of pastoral landscapes and accompanying maps which use, as their starting point, portrait postcards of Great War soldiers (in particular, elements found on the studio backdrops against which they were photographed) and Trench maps. Although the pastoral scenes will be empty – devoid of human life – I aim nonetheless to create a sense that people have been there; that the landscape is remembering them – an absence rather than a lack. This will serve to articulate the journeys of those soldiers, from photographic studio to the Front, and for many, death.

Two quotes are useful here; the first from Rainer Maria Rilke’s Duino Elegies:

“Look, trees exist.

The houses we live in continue to stand. Only we

pass away like air traded for air and everything

conspires to maintain silence about us, perhaps

half out of shame, half out of unspeakable hope.”

The other from Wordsworth’s Guide to the District of the Lakes:

“…we can only imagine ‘the primeval woods shedding and renewing their leaves with no human eye to notice or human heart to regret or welcome the change.'”

In Rilke’s poem, the idea of trees (among other things) remembering through their silence those who’ve passed amongst them is particularly appealing and finds a kind of reversed echo in Wordworth’s imaginings of the primeval woods: where it isn’t the human heart regretting or welcoming the change, rather the trees, regretting (or welcoming) our absence.

Words from war poet Edward Thomas serve to further this idea of ‘remembering trees’. In the Rose Acre Papers, a collection of essays published in 1904 he writes:

“…a bleak day in February, when the trees moan as if they cover a tomb, the tomb of the voices, the thrones and dominations, of summer past.”

His widow, Helen, writing after the war in ‘World Without End,’ described how the “snow still lay deep under the forest trees, which tortured by the merciless wind moaned and swayed as if in exhausted agony.’

It’s almost the same lamenting her husband had described before the war.

Richard Hayman, writing in ‘Trees – Woodlands and Western Civilization’ states that “woods are poised between reality and imagination…” As a child woods were, for me, a means of accessing both my imagination and the distant past; a place “for chance encounters” with historical figures, monsters and knights. Woods, as Hayman puts it, are places which can “take protagonists from their everyday lives” while, as I would add, keeping them grounded in the reality of the present.

As a child I would often create maps of imagined landscapes covered – like my imagined mediaeval world – by vast swathes of forest. And as an adult, the act of drawing them returns me to a place where my childhood and the distant past coexist; “a mixture of personal memory and cultivated myth” grounded in the nowness of the present. As such, the ‘pastoral’ landscapes I’m going to paint, based on those strange and incongruous studio backdrops, become too, landscapes of childish sylvan fancies.

When considering the war, much of our attention is, naturally, focused through the lens of its duration: the years 1914-1918. But every one of those men who fought in the trenches was once a child, and since becoming a father this has become an important aspect of my ability to empathise. To empathise, we must see these men unencumbered by the hindsight which history affords us; as men who lived lives before 1914 and beyond the theatre of war. I return to Paul Fussell’s quote (“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral”) and add that we must also see the soldiers who fought not as men, but as children. Again, the words of Edward Thomas serve to articulate this idea; the “summer past” including perhaps those lost years of childhood. Neil Hanson, writing in ‘The Unknown Soldier’ talks of how, on the eve of the Battle of the Somme, the smell in the air was that of an English summer – of fresh cut grass; the smell – one could say – of memories; of childhood.

Returning to Rilke’s Duino Elegies we find another dimension to these landscapes.

And gently she guides him through the vast

Keening landscape, shows him temple columns,

ruins of castles from which the Keening princes

Once wisely governed the land. She shows him

the towering trees of tears, the fields of melancholy

in bloom (the living know this only in gentle leaf).

These pastoral landscapes become therefore, not only the landscapes of childhood imaginings, of “personal memory and cultivated myth”, but the landscape of mourning. The words of Edward and Helen Thomas are especially poignant in this regard; Edward’s trees mourn for a long-lost past; Helen’s for an empty future.

War and The Pastoral Landscape

I’ve been thinking these last few weeks about a new body of work based on the First World War. For a long time – as will be evident from my blog – I’ve been looking at ways of using the backdrops of numerous World War I postcards.

A quote from Paul Fussell has been especially helpful in this regard.

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

The images on the backdrops are these proposed moments.

As a contemporary artist living so long after the war, it is of course impossible for me to create works about the war itself. What I can do however is comment on my relationship to the war (and those affected by it) by creating scenes – pastoral scenes – which use as their starting point the backdrops of World War I postcards.

The pastoral will, therefore, be articulated through the language of war.

These pastoral images will, predominantly, be woodscapes based on places I have visited over the last few years including Hafodyrynys (where my great-great-uncle, Jonah Rogers (1892-1915) grew up), Verdun and the Somme. They might contain – to quote Rilke – ‘…temple columns, ruins of castles’ as per the slightly less pastoral backdrops. They will be devoid of people; the soldiers absent as if they had melted into the backdrops – as if these pastoral scenes represent the Keening landscape of Rilke’s Duino Elegies.

As I’ve written before: it is this absence which the trees express so silently, so eloquently. As Rilke so perfectly puts it:

‘Look, trees exist.

The houses we live in continue to stand. Only we

pass away like air traded for air and everything

conspires to maintain silence about us, perhaps

half out of shame, half out of unspeakable hope.’

The woods I paint will be based, as I’ve said, on those places I have visited as well as those idealised scenes in front of which the soldiers stand in the postcards. They will be – as Richard Hayman puts it – woods “poised between reality and imagination…” – shame and unspeakable hope.

Again as I’ve written before: After the war, the sense of emptiness must have been everywhere. Every insignificant moment – barely acknowledged before the war – now pregnant with a sense of incomprehensible loss. The world, outwardly the same, had shifted just a little, but it had taken the lives of millions to push it there.

There is in this text a sense of absence but also of movement, of continuation – however slight or small (something I want to record in my work). And there’s a link between this and a quote from William Wordsworth who wrote in his Guide to the District of the Lakes: we can only imagine ‘the primeval woods shedding and renewing their leaves with no human eye to notice or human heart to regret or welcome the change.’ I somehow want to turn this quote on its head and borrow from Rilke, who in his Duino Elegies describes the towering trees of tears. I want to paint scenes where there are no people, but in which their absence is recorded, primarily by the trees silently remembering.

“The painter sees the trees, the trees see the painter.”

Absence

In the Tenth Elegy of Rilke’s Duino Elegies we read:

‘…Our ancestors

worked the mines, up there in the mountain range.

Among men, sometimes you still find polished lumps

of original grief or – erupted from an ancient volcano –

a petrified clinker of rage. Yes. That came

from up there. Once we were rich in such things…’

And gently she guides him through the vast

Keening landscape, shows him temple columns,

ruins of castles from which the Keening princes

Once wisely governed the land. She shows him

the towering trees of tears, the fields of melancholy

in bloom (the living know this only in gentle leaf).

And she shows him grazing herds of mourning

and sometimes a startled bird draws far off

and scrawls flatly across their upturned gaze

and flies an image of its solitary cry….

Dizzied still by his early death, the youth’s eyes

can hardly grasp it. But her gaze frightens

an owl from the crown’s brim so it brushes

slow strokes downwards on the cheek – the one

with the fullest curve – and faintly,

in death’s newly sharpened sense of hearing,

as on a double and unfolded page,

it sketches for him the indescribable outline.

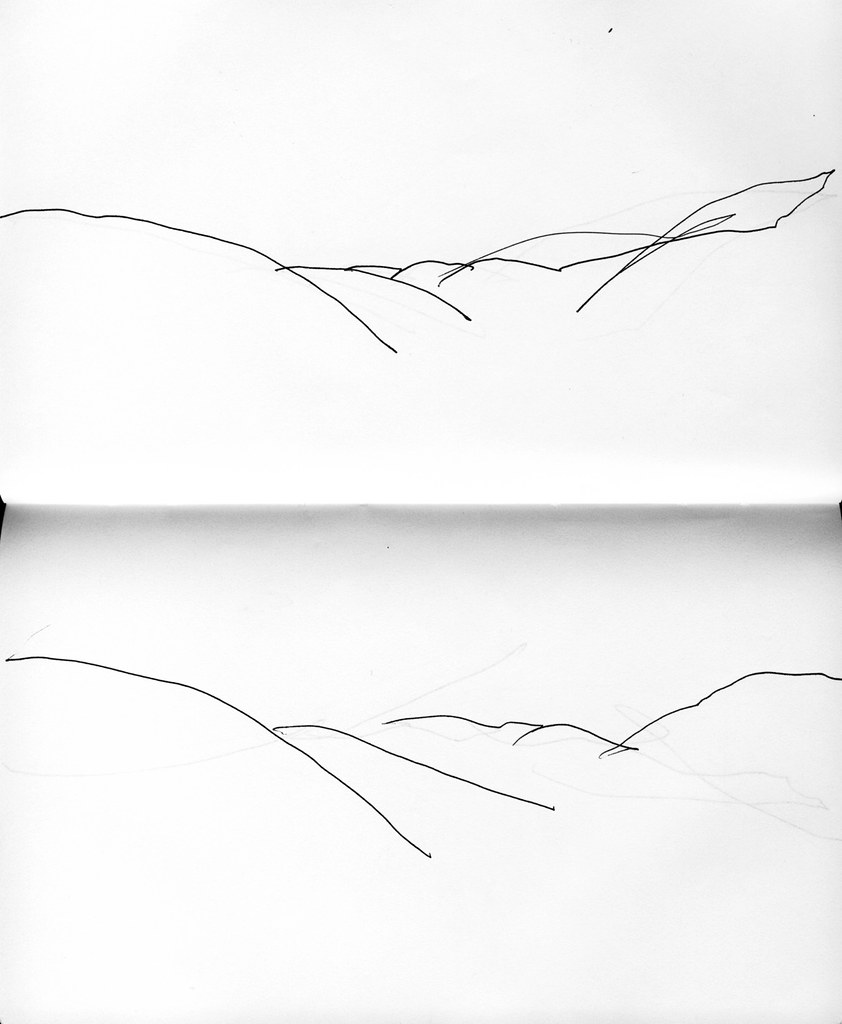

I’ve read this poem numerous times but on a recent reading, the first and last two lines reminded me of some sketches I made during a visit to Hafodyrynys, a town in Wales where my grandmother was born. My great-grandfather, Elias, used to walk from their house, up ‘the mountain’ as my grandmother called it, to Llanhilleth where he worked in the mine. Following in his footsteps, and walking the path he walked almost every day over 100 years ago, I thought of how the shape of the view had barely changed. I sketched it: an indescribable outline on a double and unfolded page.

A young boy in a flat cap pulled over his face

A bell tolls

A girl on her computer sits at the window looking out

Blue, yellow and white balloons

Two distant blasts of a train horn made bigger by the stillness of the air

The cackle of a bird

With regards gesture: Rilke said that the “depth of time” was revealed more in human gestures than in archaeological remains or fossilised organisms. The gesture is a “fossil of movement”; it is, at the same time, the very mark of the fleeting present and of desire in which our future is formed.

The concept of a ‘depth of time’ leads me to consider the phrase ‘a distant past’. How can the past be distant (or otherwise) if the past no longer exists? How can we measure that which we cannot empirically observe? My getting up this morning is as much a part of the past as, for example, the death of Richard III, yet of course there is a difference; a scale of pastness. But how can we measure pastness? We can of course use degrees of time, seconds through to years and millennia, but somehow it seems inadequate. For me, pastness can also be expressed through absence (in particular that of people) and it is this absence which the trees express so silently, so eloquently. “William Wordsworth, writing in his Guide to the District of the Lakes, wrote that we can only imagine ‘the primeval woods shedding and renewing their leaves with no human eye to notice or human heart to regret or welcome the change.'”

‘Look,’ says Rilke, ‘trees exist.

The houses we live in continue to stand. Only we

pass away like air traded for air and everything

conspires to maintain silence about us, perhaps

half out of shame, half out of unspeakable hope.’

When speaking of distance in relation to the past (the distant past), I think of distance as it’s perceived in the landscape; a measurement defining the space between me and something else. Putting the two together, the ‘distant past’ becomes something internal, carried in relation to the external world; the sum of those absences I carry through the landscape.

Rilke’s description of the Keening landscape reminded me too of the landscapes which I created as a child (see also Maps). These were ‘places’ based on how I perceived the landscape of the past; in particular, its swathes of ancient and unspoiled forests. As Richard Hayman puts it: “woods are poised between reality and imagination…” Whenever I was in a wood – however small – I always experienced it with my imagination.

Which brings me round to recent work I’ve been doing on World War I backdrops.

Seeing the young soldier standing before a bucolic backdrop, one is reminded of the youth in Rilke’s poem being led through the Keening landscape.

For some time, I’ve been wanting to create landscapes based on these postcards, landscapes about the Great War which do not seek to illustrate its horrors but articulate our present day relationship to it. A quote by Paul Fussell is important in this respect:

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

The landscape behind the soldier becomes the Keening landscape described by Rilke, a moment of pastoral as described by Fussell. In the right hand image, the soldier has gone; the landscape is one filled with ‘the towering trees of tears, the fields of melancholy.’ It is an image of the past: as Ruskin wrote: a tree “is always telling us about the past, never about the future.” It is an image of absence, a kind of which only the trees can speak.

Paul Nash Quote

“Here in the back garden of the trenches it is amazingly beautiful – the mud is dried to a pinky colour and upon the parapet, and through sandbags even, the green grass pushes up and waves in the breeze, while clots of bright dandelions, clover, thistles and twenty other plants flourish luxuriantly, brilliant growths of bright green against the pink earth. Nearly all the better trees have come out, and the birds sing all day in spite of shells and shrapnel…”

The Keening Landscape

The First World War: this young soldier would have played his part; perhaps one of the nearly 900,000 British men killed in action. Or one of the over 1.6 million wounded. But there is nothing in the backdrop or prop that points us towards that tale. Just the costume.

So what story does the scenery tell us? A soldier stands in a landscape; an idyllic world seemingly untouched yet threatened by a war in which the soldier has yet to play his part. (Or rather, the war has yet to play a part in the soldier’s life: an important distinction, for if the story or ‘play’ is History, then this soldier’s part would be a minor one. Imagine a vast stage, filled with hundreds, maybe thousands of actors. Most of them would say nothing, remaining part of the anonymous ‘chorus’ (exiting and entering the stage) leaving the lead actors, playing the parts of named politicians and Generals, to speak any lines. Yet of course, in his own life story, this soldier would play the lead. It would be as if towards the end of the ‘play’, one of those hundreds or thousands of extras making up the chorus, would step forward and begin to speak.)

Quotes from ‘Trees’

Trees – Woods and Western Civilisation by Richard Hayman

“…the forest provides the setting for chance encounters that take the protagonists away from their everyday lives. Woodland is the gateway to a parallel reality of the underworld, but it is also a refuge where the real world is held in limbo.”

“Woods are poised between reality and imagination…”

Trees

In his book, Trees – Woodlands and Western Civilization, archaeologist Richard Hayman writes:

“…the forest provides the setting for chance encounters that take the protagonists away from their everyday lives. Woodland is the gateway to a parallel reality of the underworld, but it is also a refuge where the real world is held in limbo.”

“Woods,” he says, “are poised between reality and imagination…” They have “roots in the ground and reach up to the sky linking earth with heaven.” They “span many lifetimes” and in this sense can be seen to link the past and present too.

When I visited Auschwitz-Birkenau in 2006, it was the trees (pictured below) which most unnerved me. The way they moved in the breeze – just as they would have done at the height of Holocaust. It was this ‘everydayness’ which, for a second, enabled me to straddle past and present.

Portals to the past, these trees were once gateways to death. It was amongst these trees that victims were kept before being sent to the gas chambers nearby.

A work I created in 2009 – The Woods, Breathing – took the form of words taken from two books: one the Diary of Adam Czerniakow, the other, Pilgrims of the Wild by Grey Owl, a book which Czerniakow had read in the Warsaw ghetto.

The words were planted amongst the trees of Shotover. Some of them – quite mundane – could almost have been describing the place in which I had placed them. For example, ‘Silver birches’ pictured below.

Others, like ‘Identity Papers’ (below) called to mind the reality of Czerniakow’s world; one not so dissimilar from ours, in terms of the fact it was real.

A quote from his diary illustrates this: “In Otwock. The air, the woods, breathing.” It describes a moment of respite from the horrors of the ghetto and while we might find it hard, despite our greater efforts, to empathise with life in such appalling conditions, we can empathise much more readily with that moment in the woods.

Below is a painting by Paul Nash entitled ‘We are Making a New World.’

The trees in this landscape have been splintered by shellfire. The following extract from Neil Hanson’s book The Unknown Soldier is a vivid description of the landscape Nash is depicting.

Clearly visible on the skyline, High Wood was a long low hill, a natural strong point, the highest ground in this low-lying area. Densely forested when the fighting began, the months of incessant shelling had left it a wood in name only, reduced to a wasteland of of shell-holes, over-running with water, its trees splintered to matchwood, leaving smashed stumps barely two feet above the ground, and shattered rock and churned earth, like a sea all heaving in anger.

Below is a trench map showing various woods in an area of The Somme.

One could say the Great War was the start of the modern age; the past, in the form of dense woods had been obliterated.

The woods have grown back and walking within them, it’s almost impossible to appreciate what they were like for soldiers during the Great War. As in Auschwitz-Birkenau, it was the nowness of my being there, of experiencing the present in, for example, the moving of the trees, that enabled me to establish some kind of connection with those who had lived through such a catastrophic event. With the return of the trees comes the return of the past.

Shadows 3

I was looking at something recently which made me think of the work I’ve been exploring around the backdrops used in World War One postcards, such as that below:

Painted Trees

New Work 3

New Work 2

New Work

Past and Present Postcard

The image below is the last in a series I’ve made using both an original World War One postcard and a photograph I took in Verdun. All are works in progress.

I’ve been fascinated with the backdrops in some of these postcards for quite some time now and have been looking at ways of using them in works relating to the Great War and, in particular, the issue of empathy.

The original postcard is of course in black and white (with a greenish tint) and shows a soldier about to head to the Front, standing, leaning on a chair.

Behind him is an idealised image – an idyllic, invented landscape, a far cry from what he was, perhaps, about to encounter, but close in some respects to what we find on battlefields today; where there were trenches, arms, barbed wire and bodies, there are now trees. And amidst the trees, incongruous concrete Pill Boxes stand and watch as the seasons come and go. Everything is slowly reclaimed. The trees in the image at the top of the blog spill to reclaim the past – the interior of the studio – through the gap left by the missing soldier.

I have placed the solider back beyond the gap left by the vague shape of his own body, to remind us that people like the soldiers we see in all these postcards, were once like those of us who have visited the battlefields. They too would have known what it was to stand in a wood. To listen to the wind blowing through the branches.

To stand and do just that, is one way to remember them.