Another triptych comprising photographs taken on Sunday at Shotover.

Trees Triptych

A triptych comprising photographs taken at Shotover on Sunday.

A Walk in Shotover Wood

On what was a beautiful Autumn day, I took a walk to Shotover wood to take some photos of trees. I’ve always loved Shotover, both for its place in my past and that of my family, and its own history, being as it once was the main road to London (the mounting steps at the top and bottom of the hill are particularly interesting). The following images are a few of the photographs I took.

Trees and Other Projects

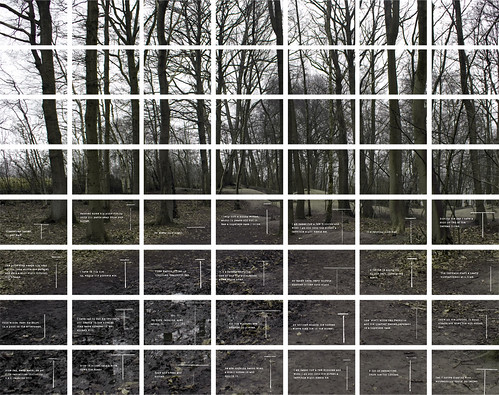

I have been photographing the same trees – shown above – for almost 18 months now, and what started as a simple photographic record of a particular set of trees has since morphed into a project which shares certain aspects with other lines of research. I was drawn to them initially by their shape and proportions; by the fact that they reminded me of an Isaac Levitan painting, such as that below.

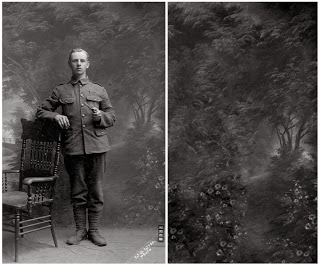

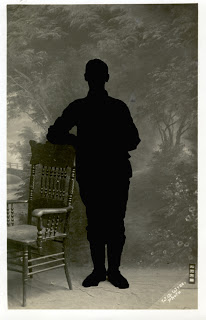

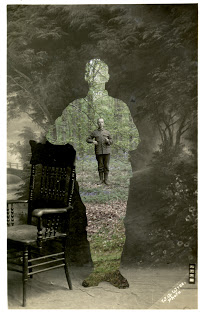

Since then, as my personal circumstances have changed through separation, the trees have come to signify something else. Being separated from my children for much of the week, there’s a connection between this anxiety and that which is present in the postcards of World War I servicemen, photographed in studios before they left for the Front, often against a painted backdrop of trees.

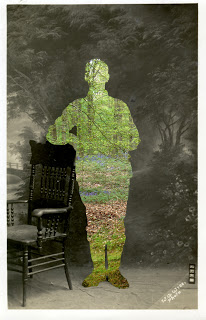

I worked on this theme previously, working with postcards such as that above and creating montages that used photographs I’d taken of trees at one-time battlefields such as the Somme and Verdun.

The Lawn and the Woods

I remember as a small boy how my Nana would on occasion take me and my older brother to where she worked as a Housekeeper. The house was – at far as I recall – a big, white, Modernist building with a large well-kept lawn at the rear. But what I remember most was the wood which stood at the edge of the garden. I can see it now – that contrast between the manicured lawn and the wild dark of the trees, and with the work that I’ve been doing on gardens, trees and contrasts, this particular memory has suddenly sprung to life.

Lamenting Trees

‘Ghastly by day, ghostly by night, the rottenest place on the Somme’. Such was how soldiers described High Wood, one of the many that peppered the battlefields of Flanders and France. Woods in name only, these once dense places were quickly reduced to matchwood. One officer, writing of Sanctuary Wood near Ypres, declared that: ‘Dante in his wildest imaginings never conceived the like.’

We, in our wildest imaginations can not conceive the like. So how can we remember and empathise with those who for whom it was real? Historian Paul Fussell provides a starting point:

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

I aim therefore to create a series of pastoral landscapes and accompanying maps which use, as their starting point, portrait postcards of Great War soldiers (in particular, elements found on the studio backdrops against which they were photographed) and Trench maps. Although the pastoral scenes will be empty – devoid of human life – I aim nonetheless to create a sense that people have been there; that the landscape is remembering them – an absence rather than a lack. This will serve to articulate the journeys of those soldiers, from photographic studio to the Front, and for many, death.

Two quotes are useful here; the first from Rainer Maria Rilke’s Duino Elegies:

“Look, trees exist.

The houses we live in continue to stand. Only we

pass away like air traded for air and everything

conspires to maintain silence about us, perhaps

half out of shame, half out of unspeakable hope.”

The other from Wordsworth’s Guide to the District of the Lakes:

“…we can only imagine ‘the primeval woods shedding and renewing their leaves with no human eye to notice or human heart to regret or welcome the change.'”

In Rilke’s poem, the idea of trees (among other things) remembering through their silence those who’ve passed amongst them is particularly appealing and finds a kind of reversed echo in Wordworth’s imaginings of the primeval woods: where it isn’t the human heart regretting or welcoming the change, rather the trees, regretting (or welcoming) our absence.

Words from war poet Edward Thomas serve to further this idea of ‘remembering trees’. In the Rose Acre Papers, a collection of essays published in 1904 he writes:

“…a bleak day in February, when the trees moan as if they cover a tomb, the tomb of the voices, the thrones and dominations, of summer past.”

His widow, Helen, writing after the war in ‘World Without End,’ described how the “snow still lay deep under the forest trees, which tortured by the merciless wind moaned and swayed as if in exhausted agony.’

It’s almost the same lamenting her husband had described before the war.

Richard Hayman, writing in ‘Trees – Woodlands and Western Civilization’ states that “woods are poised between reality and imagination…” As a child woods were, for me, a means of accessing both my imagination and the distant past; a place “for chance encounters” with historical figures, monsters and knights. Woods, as Hayman puts it, are places which can “take protagonists from their everyday lives” while, as I would add, keeping them grounded in the reality of the present.

As a child I would often create maps of imagined landscapes covered – like my imagined mediaeval world – by vast swathes of forest. And as an adult, the act of drawing them returns me to a place where my childhood and the distant past coexist; “a mixture of personal memory and cultivated myth” grounded in the nowness of the present. As such, the ‘pastoral’ landscapes I’m going to paint, based on those strange and incongruous studio backdrops, become too, landscapes of childish sylvan fancies.

When considering the war, much of our attention is, naturally, focused through the lens of its duration: the years 1914-1918. But every one of those men who fought in the trenches was once a child, and since becoming a father this has become an important aspect of my ability to empathise. To empathise, we must see these men unencumbered by the hindsight which history affords us; as men who lived lives before 1914 and beyond the theatre of war. I return to Paul Fussell’s quote (“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral”) and add that we must also see the soldiers who fought not as men, but as children. Again, the words of Edward Thomas serve to articulate this idea; the “summer past” including perhaps those lost years of childhood. Neil Hanson, writing in ‘The Unknown Soldier’ talks of how, on the eve of the Battle of the Somme, the smell in the air was that of an English summer – of fresh cut grass; the smell – one could say – of memories; of childhood.

Returning to Rilke’s Duino Elegies we find another dimension to these landscapes.

And gently she guides him through the vast

Keening landscape, shows him temple columns,

ruins of castles from which the Keening princes

Once wisely governed the land. She shows him

the towering trees of tears, the fields of melancholy

in bloom (the living know this only in gentle leaf).

These pastoral landscapes become therefore, not only the landscapes of childhood imaginings, of “personal memory and cultivated myth”, but the landscape of mourning. The words of Edward and Helen Thomas are especially poignant in this regard; Edward’s trees mourn for a long-lost past; Helen’s for an empty future.

War and The Pastoral Landscape

I’ve been thinking these last few weeks about a new body of work based on the First World War. For a long time – as will be evident from my blog – I’ve been looking at ways of using the backdrops of numerous World War I postcards.

A quote from Paul Fussell has been especially helpful in this regard.

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

The images on the backdrops are these proposed moments.

As a contemporary artist living so long after the war, it is of course impossible for me to create works about the war itself. What I can do however is comment on my relationship to the war (and those affected by it) by creating scenes – pastoral scenes – which use as their starting point the backdrops of World War I postcards.

The pastoral will, therefore, be articulated through the language of war.

These pastoral images will, predominantly, be woodscapes based on places I have visited over the last few years including Hafodyrynys (where my great-great-uncle, Jonah Rogers (1892-1915) grew up), Verdun and the Somme. They might contain – to quote Rilke – ‘…temple columns, ruins of castles’ as per the slightly less pastoral backdrops. They will be devoid of people; the soldiers absent as if they had melted into the backdrops – as if these pastoral scenes represent the Keening landscape of Rilke’s Duino Elegies.

As I’ve written before: it is this absence which the trees express so silently, so eloquently. As Rilke so perfectly puts it:

‘Look, trees exist.

The houses we live in continue to stand. Only we

pass away like air traded for air and everything

conspires to maintain silence about us, perhaps

half out of shame, half out of unspeakable hope.’

The woods I paint will be based, as I’ve said, on those places I have visited as well as those idealised scenes in front of which the soldiers stand in the postcards. They will be – as Richard Hayman puts it – woods “poised between reality and imagination…” – shame and unspeakable hope.

Again as I’ve written before: After the war, the sense of emptiness must have been everywhere. Every insignificant moment – barely acknowledged before the war – now pregnant with a sense of incomprehensible loss. The world, outwardly the same, had shifted just a little, but it had taken the lives of millions to push it there.

There is in this text a sense of absence but also of movement, of continuation – however slight or small (something I want to record in my work). And there’s a link between this and a quote from William Wordsworth who wrote in his Guide to the District of the Lakes: we can only imagine ‘the primeval woods shedding and renewing their leaves with no human eye to notice or human heart to regret or welcome the change.’ I somehow want to turn this quote on its head and borrow from Rilke, who in his Duino Elegies describes the towering trees of tears. I want to paint scenes where there are no people, but in which their absence is recorded, primarily by the trees silently remembering.

“The painter sees the trees, the trees see the painter.”

Absence

In the Tenth Elegy of Rilke’s Duino Elegies we read:

‘…Our ancestors

worked the mines, up there in the mountain range.

Among men, sometimes you still find polished lumps

of original grief or – erupted from an ancient volcano –

a petrified clinker of rage. Yes. That came

from up there. Once we were rich in such things…’

And gently she guides him through the vast

Keening landscape, shows him temple columns,

ruins of castles from which the Keening princes

Once wisely governed the land. She shows him

the towering trees of tears, the fields of melancholy

in bloom (the living know this only in gentle leaf).

And she shows him grazing herds of mourning

and sometimes a startled bird draws far off

and scrawls flatly across their upturned gaze

and flies an image of its solitary cry….

Dizzied still by his early death, the youth’s eyes

can hardly grasp it. But her gaze frightens

an owl from the crown’s brim so it brushes

slow strokes downwards on the cheek – the one

with the fullest curve – and faintly,

in death’s newly sharpened sense of hearing,

as on a double and unfolded page,

it sketches for him the indescribable outline.

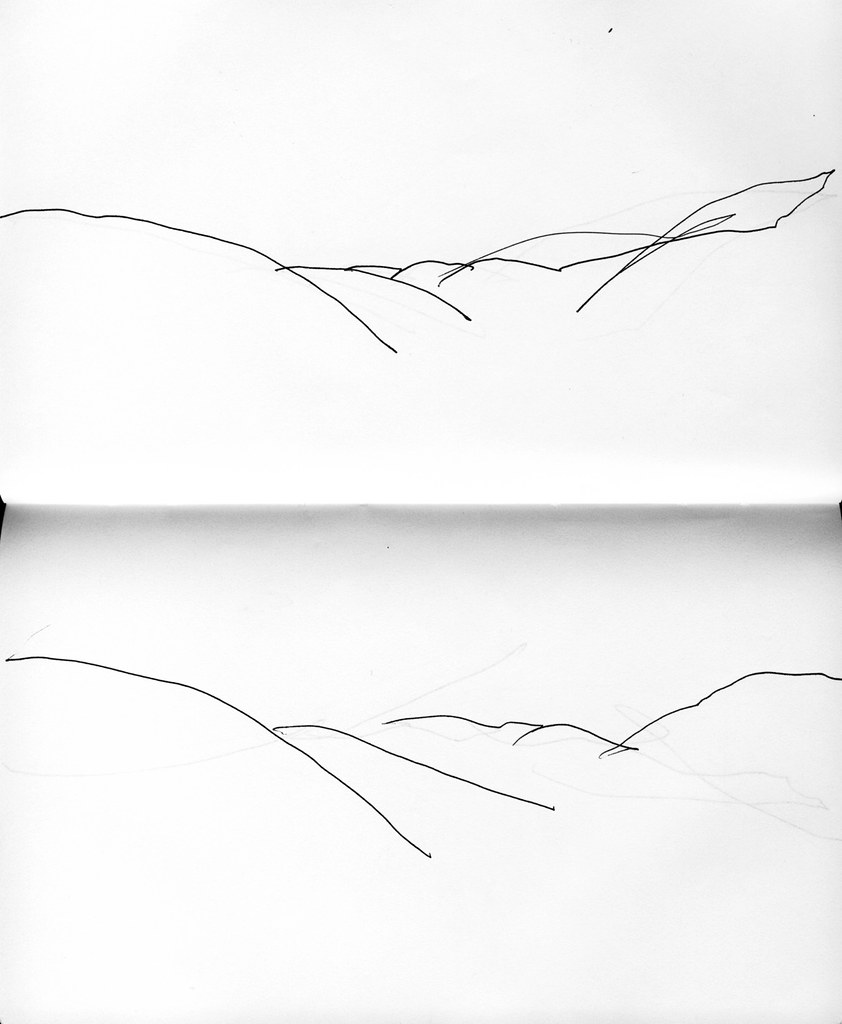

I’ve read this poem numerous times but on a recent reading, the first and last two lines reminded me of some sketches I made during a visit to Hafodyrynys, a town in Wales where my grandmother was born. My great-grandfather, Elias, used to walk from their house, up ‘the mountain’ as my grandmother called it, to Llanhilleth where he worked in the mine. Following in his footsteps, and walking the path he walked almost every day over 100 years ago, I thought of how the shape of the view had barely changed. I sketched it: an indescribable outline on a double and unfolded page.

A young boy in a flat cap pulled over his face

A bell tolls

A girl on her computer sits at the window looking out

Blue, yellow and white balloons

Two distant blasts of a train horn made bigger by the stillness of the air

The cackle of a bird

With regards gesture: Rilke said that the “depth of time” was revealed more in human gestures than in archaeological remains or fossilised organisms. The gesture is a “fossil of movement”; it is, at the same time, the very mark of the fleeting present and of desire in which our future is formed.

The concept of a ‘depth of time’ leads me to consider the phrase ‘a distant past’. How can the past be distant (or otherwise) if the past no longer exists? How can we measure that which we cannot empirically observe? My getting up this morning is as much a part of the past as, for example, the death of Richard III, yet of course there is a difference; a scale of pastness. But how can we measure pastness? We can of course use degrees of time, seconds through to years and millennia, but somehow it seems inadequate. For me, pastness can also be expressed through absence (in particular that of people) and it is this absence which the trees express so silently, so eloquently. “William Wordsworth, writing in his Guide to the District of the Lakes, wrote that we can only imagine ‘the primeval woods shedding and renewing their leaves with no human eye to notice or human heart to regret or welcome the change.'”

‘Look,’ says Rilke, ‘trees exist.

The houses we live in continue to stand. Only we

pass away like air traded for air and everything

conspires to maintain silence about us, perhaps

half out of shame, half out of unspeakable hope.’

When speaking of distance in relation to the past (the distant past), I think of distance as it’s perceived in the landscape; a measurement defining the space between me and something else. Putting the two together, the ‘distant past’ becomes something internal, carried in relation to the external world; the sum of those absences I carry through the landscape.

Rilke’s description of the Keening landscape reminded me too of the landscapes which I created as a child (see also Maps). These were ‘places’ based on how I perceived the landscape of the past; in particular, its swathes of ancient and unspoiled forests. As Richard Hayman puts it: “woods are poised between reality and imagination…” Whenever I was in a wood – however small – I always experienced it with my imagination.

Which brings me round to recent work I’ve been doing on World War I backdrops.

Seeing the young soldier standing before a bucolic backdrop, one is reminded of the youth in Rilke’s poem being led through the Keening landscape.

For some time, I’ve been wanting to create landscapes based on these postcards, landscapes about the Great War which do not seek to illustrate its horrors but articulate our present day relationship to it. A quote by Paul Fussell is important in this respect:

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

The landscape behind the soldier becomes the Keening landscape described by Rilke, a moment of pastoral as described by Fussell. In the right hand image, the soldier has gone; the landscape is one filled with ‘the towering trees of tears, the fields of melancholy.’ It is an image of the past: as Ruskin wrote: a tree “is always telling us about the past, never about the future.” It is an image of absence, a kind of which only the trees can speak.

The Keening Landscape

The First World War: this young soldier would have played his part; perhaps one of the nearly 900,000 British men killed in action. Or one of the over 1.6 million wounded. But there is nothing in the backdrop or prop that points us towards that tale. Just the costume.

So what story does the scenery tell us? A soldier stands in a landscape; an idyllic world seemingly untouched yet threatened by a war in which the soldier has yet to play his part. (Or rather, the war has yet to play a part in the soldier’s life: an important distinction, for if the story or ‘play’ is History, then this soldier’s part would be a minor one. Imagine a vast stage, filled with hundreds, maybe thousands of actors. Most of them would say nothing, remaining part of the anonymous ‘chorus’ (exiting and entering the stage) leaving the lead actors, playing the parts of named politicians and Generals, to speak any lines. Yet of course, in his own life story, this soldier would play the lead. It would be as if towards the end of the ‘play’, one of those hundreds or thousands of extras making up the chorus, would step forward and begin to speak.)

Quotes from ‘Trees’

Trees – Woods and Western Civilisation by Richard Hayman

“…the forest provides the setting for chance encounters that take the protagonists away from their everyday lives. Woodland is the gateway to a parallel reality of the underworld, but it is also a refuge where the real world is held in limbo.”

“Woods are poised between reality and imagination…”

Trees

In his book, Trees – Woodlands and Western Civilization, archaeologist Richard Hayman writes:

“…the forest provides the setting for chance encounters that take the protagonists away from their everyday lives. Woodland is the gateway to a parallel reality of the underworld, but it is also a refuge where the real world is held in limbo.”

“Woods,” he says, “are poised between reality and imagination…” They have “roots in the ground and reach up to the sky linking earth with heaven.” They “span many lifetimes” and in this sense can be seen to link the past and present too.

When I visited Auschwitz-Birkenau in 2006, it was the trees (pictured below) which most unnerved me. The way they moved in the breeze – just as they would have done at the height of Holocaust. It was this ‘everydayness’ which, for a second, enabled me to straddle past and present.

Portals to the past, these trees were once gateways to death. It was amongst these trees that victims were kept before being sent to the gas chambers nearby.

A work I created in 2009 – The Woods, Breathing – took the form of words taken from two books: one the Diary of Adam Czerniakow, the other, Pilgrims of the Wild by Grey Owl, a book which Czerniakow had read in the Warsaw ghetto.

The words were planted amongst the trees of Shotover. Some of them – quite mundane – could almost have been describing the place in which I had placed them. For example, ‘Silver birches’ pictured below.

Others, like ‘Identity Papers’ (below) called to mind the reality of Czerniakow’s world; one not so dissimilar from ours, in terms of the fact it was real.

A quote from his diary illustrates this: “In Otwock. The air, the woods, breathing.” It describes a moment of respite from the horrors of the ghetto and while we might find it hard, despite our greater efforts, to empathise with life in such appalling conditions, we can empathise much more readily with that moment in the woods.

Below is a painting by Paul Nash entitled ‘We are Making a New World.’

The trees in this landscape have been splintered by shellfire. The following extract from Neil Hanson’s book The Unknown Soldier is a vivid description of the landscape Nash is depicting.

Clearly visible on the skyline, High Wood was a long low hill, a natural strong point, the highest ground in this low-lying area. Densely forested when the fighting began, the months of incessant shelling had left it a wood in name only, reduced to a wasteland of of shell-holes, over-running with water, its trees splintered to matchwood, leaving smashed stumps barely two feet above the ground, and shattered rock and churned earth, like a sea all heaving in anger.

Below is a trench map showing various woods in an area of The Somme.

One could say the Great War was the start of the modern age; the past, in the form of dense woods had been obliterated.

The woods have grown back and walking within them, it’s almost impossible to appreciate what they were like for soldiers during the Great War. As in Auschwitz-Birkenau, it was the nowness of my being there, of experiencing the present in, for example, the moving of the trees, that enabled me to establish some kind of connection with those who had lived through such a catastrophic event. With the return of the trees comes the return of the past.

Shadows 3

I was looking at something recently which made me think of the work I’ve been exploring around the backdrops used in World War One postcards, such as that below:

Painted Trees

New Work 3

New Work 2

New Work

Past and Present Postcard

The image below is the last in a series I’ve made using both an original World War One postcard and a photograph I took in Verdun. All are works in progress.

I’ve been fascinated with the backdrops in some of these postcards for quite some time now and have been looking at ways of using them in works relating to the Great War and, in particular, the issue of empathy.

The original postcard is of course in black and white (with a greenish tint) and shows a soldier about to head to the Front, standing, leaning on a chair.

Behind him is an idealised image – an idyllic, invented landscape, a far cry from what he was, perhaps, about to encounter, but close in some respects to what we find on battlefields today; where there were trenches, arms, barbed wire and bodies, there are now trees. And amidst the trees, incongruous concrete Pill Boxes stand and watch as the seasons come and go. Everything is slowly reclaimed. The trees in the image at the top of the blog spill to reclaim the past – the interior of the studio – through the gap left by the missing soldier.

I have placed the solider back beyond the gap left by the vague shape of his own body, to remind us that people like the soldiers we see in all these postcards, were once like those of us who have visited the battlefields. They too would have known what it was to stand in a wood. To listen to the wind blowing through the branches.

To stand and do just that, is one way to remember them.

Work in Progress

The Place That’s Always There (Trees)

Maps

As a child I spent many hours drawing maps of imaginary lands to which in my mind I would often escape. Over time these worlds – and one in particular (see image below) – became a very real part of my existence; I knew its towns, forests, plains and mountains; I knew the seas by which it was surrounded, the lakes and rivers and potted histories of each location. I created characters and can still to this day remember them along with the geography of the world they inhabited.

As well as being a means of navigating my imagination, the maps were also guides to the real world. Whilst out walking, I would just as likely find myself walking in my fictional landscape and as such parallels between the real and the imagined were established. To some extent these parallels still exist but it wasn’t until I started researching trench maps of the area in which my great-great-uncle Jonah Rogers was killed (near Ypres) that I was again reminded of my fictional world.

I was interested in pinpointing the place in which Jonah Rogers was killed; to see what the terrain was like and thereby understand, at least in part, something of the world he would have known. One can often imagine that the trenches were more or less just rudimentary ditches cut into the ground in which soliders lived as best they could, just a matter of yards away from the enemy, and of course, in many respects that’s precisley what they were; but the trench system was actually very complex. Far from being two lines gouged into the ground, the trenches of the opposing armies were labyrinthine as the image below reveals.

This map shows an area just outside Ypres. One can see precisely how complex the system of trenches were and yet of course the map can only tell us so much. Sanctuary Wood (shown on the left of the detail above) was described in the diary of one officer as follows:

“Of the terrible and horrible scenes I have seen in the war, Sanctuary Wood is the worst… Sanctuary Wood in 1914 was a sanctuary, but today, Dante in his wildest imaginings never conceived a like.”

It’s hard to imagine Dante’s image of hell as being in any way less horrific than anything on earth, particularly when looking at the map above.

What one can also see on another part of this map are some of the names which soldiers gave to the trenches and the areas in which they were fighting. Often names that were difficult to pronnounce were changed so that, for example, Ploegsteert became Plug Street. However, in some cases, areas were given names that made sense in terms of their being familiar names from home.

On this image one can clearly see a place called Clapham Junction. Of course there was no Clapham Junction in Belgium before the war, but by naming unfamiliar (and often utterly destroyed areas) with familiar names, soldiers and officers could, one assumes, navigate areas more easily, whether physically or in terms of reconaissance and planning. To plan attacks on places which have become muddied wastelands (to put it mildly) with few features remaining (the woods on the maps, shown as collections of lollypop trees were of course little more than burned splinters) one would need names, just as one would need names for the complex network of trenches. Could it be that by naming places with names from home, such reduced and barren landscapes (the ‘topography of Golgotha’ as Wilfred Owen called the Western Front) would appear as belonging in some way to the soldiers who fought there – was it a way of inspiring them?

The closest map – in terms of date – I could find relating to my great-great-uncle’s war, was one of St. Julien which dates from July 1915, just two months after his death in the Second Battle of Ypres. I’d wanted to get an idea of the trench system he would have been known at first hand and as I looked at the trenches shown (only German trenches were shown on this map) I found a road named after my home town; Oxford Road. Ironically, alongside this road was a cottage (one must assume there was little left of it at the time) which had been dubbed Monmouth Cottage – my great-great-uncle was from Monmouthshire.

I couldn’t help but think there was something in this naming of unfamiliar places with more familiar names which paralleled thoughts I’d had as regards my family heritage and in particular how researching it has helped me relate more easily to the past.

History is of course full of gaps. If we try and picture a place as it appeared at a given date we have to use our imaginations to fill in the holes where, for example, buildings have been razed. If we read reports or stories about events in the past we have to use our imaginations to understand the moment as fully as possible, to understand how the average person responded at the time. In doing so, we project a part of ourselves onto the past, something which is of course familiar (see ‘From Dinosaurs to Human Beings,’ OVADA Residency Blog, 2007).

Like my childhood maps of invented places, my family tree is in many ways a map of a fictional landscape, or rather a route through it. That is not to say of course that my family’s past is itself a fiction, but rather that history, in terms of how we see it in our minds is. History is in many ways a wasteland having been obliterated by time and yet there are parts of its landscape which still remain standing despite the tumult. Extant buildings, contemporaneous documents all act as pointers to a disappeared world, a world which also hides untold numbers of anonymous people. To help me navigate this landscape , I can invent my own names just as I did as a child, only this time the names will relate to, or be those of my ancestors; they will refer to dates and facts I have gleaned about their lives. In this sense I am labelling an unfamiliar, temporal landscape with familiar names, a landscape that like the battlefields of the Front has been all but destroyed. I’m filling in the gaps, mapping myself not only onto the physical world but also the past.

The worlds I invented as a child were in many ways idealised views of the real world with unspoilt forests, mediaeval cities and unpolluted seas. What faced the man at the Front was the opposite, a terrible vision of what the world could be or had become. Labelling such a world with names like Piccadilly, Buckingham Palace Road, Marylebone Road, Liverpool Street, Trafalgar Square and so on, in some ways gave it a more human face; where there were gaps, such names would fill them in perhaps with memories of home.

In the end maps are there to guide us, to reveal something about a place or perhaps a person; it all depends of course on what the map represents. We might be looking at maps of countries or maps of the brain – Katherine Harmon’s book ‘Personal Geographies and other Maps of the Imagination‘ is a great resource in this respect. When I look at the map of my invented world, I am not so much presented with a means of navigating a fictional world but rather a map of my own childhood. Looking at the place names I can in fact see the real world as it was at the time. The map therefore becomes a representation of something entirely different. The same could be said of the Trench Maps. They are maps of something quite unimaginable; if we took one and stood on a battlefield today it might offer us a hint of the way things were. But with the names of the trenches, roads, farms and cottages, they become maps of somewhere entirely different – a fictional place built only from memories. But those memories conjured by the names listed above – Piccadilly, Trafalgar Square etc. – are our memories, we can only imagine Trafalgar Square as it is today or as it is within our own minds. What we can establish, with the help of these maps, is an understanding of a sense of dislocation, between the solider in the trenches and his life back home. They serve to make those who fought and died in the war much more real.

With regards a map of my family tree I can place my ancestors in different parts of the country but of course none of them lived their lives standing still. Again there are gaps to be filled and whereas to fill in the gaps of history one can use one’s imagination, with regards the mapping of my ancestry and individual people, it is through walking around the places that they inhabited that these gaps can be filled. To close, I return to the blog entry I made during a residency at OVADA. In it I wrote:

“These invented worlds became, as I grew up, the ‘invented’ or imagined landscapes of Oxford’s past; landscapes that were – just as they still are – created from fragments, parts of the past which are still extant in the city; old buildings, walls, objects and so on. Between these structures, these fragments, I would fill the gaps, with my own imagination, with thoughts derived from my own experience. The city’s past and the past in general, as it exists within my mind, is then, to use the metaphor of cloning in Jurassic Park, a cloned dinosaur. The extant buildings, structures and objects within museums, are like the mosquitoes trapped inside the amber. They are broken strands of DNA. All that is required is for me to fill the gaps, and this I can do with my own DNA. I am in effect, the frog.

This metaphor is interesting in that DNA patterns are, of course, unique to everyone. My DNA is different to everybody else’s as there’s is to mine. Therefore, using my imagination to plug in the gaps of the past, means that the ‘past’ will comprise large parts of my own experience; my dinosaur will contain elements of my own being. (See ‘Postcard 1906’). But although my DNA is unique, it is nonetheless derived from my own past, elements have been passed down by my ancestors from time immemorial. The code which makes me who I am, comprises parts of people I know now (parents and grandmothers), people I knew (grandfathers and great-grandmother) and people lost to the past altogether (great-great grandparents and so on). What interests me about this, is that, through stating above how ‘my dinosaur will contain elements of my own being’ I can now see that ‘my dinosaur’ will contain elements of my own being, which is itself comprised of elements of hundreds – thousands – of people, the majority of whom I will of course never know and who have been dead for centuries. I like to think therefore, that ‘my dinosaur’ and my imagination aren’t entirely unique.”

In the traditional diagram of the family tree each individual is isolated, joined to others by means of a single line, almost as if they appeared at one point, moved a bit and passed the baton on to the next in line. Of course things are much more complex than this; individuals overlap in terms of the length of their lives and if we were to try and represent an individual’s journey through life, the line would be impossibly complex. Inevitably there are gaps which as I’ve said I can fill (at least, in part) by walking in the places they would have walked. In Wales, where my Grandmother grew up I found it incredible to think that this place I’d never been to and the streets, lanes and hills I had never walked, had all played a part in my existence. Without them I would not be here, or indeed there. I was then filling in the gaps, like the frog DNA in Jurassic Park, but the dinosaur I spoke of in the extract above was not so much History in this case, but me.