Recently purchased photographs.

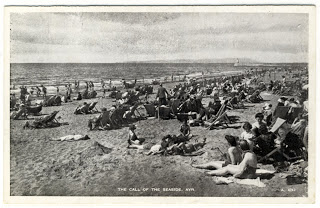

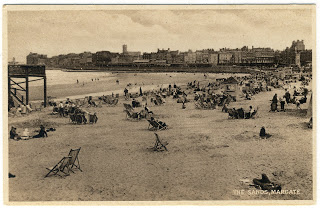

Deckchairs 3

Details

Deckchairs 2

Dust Motes II

Two photographs taken from the archives of the Czechoslovakian secret police and two photographs from a piece of mine called Broken Toys.

An Act of Imagination

There’s a shop in Paris where I like to go, whenever I am there. In a box you can rummage through a small pile of photographs, miscellaneous images, nothing overly special, but for a few Euros one of them can be yours. That shown below is the last one I bought.

The photograph is small; two and a half by three and a quarter inches. It’s damaged and indistinct; blurred in parts, but nonetheless one can see the interior of a church, within which a small group of women and girls stand facing towards the altar. The photograph was taken from above, perhaps from a gallery opposite the pulpit which one can see on the opposite wall. The pulpit’s draped in material, whether that’s normal or for a special occasion I cannot say. I cannot tell what is going in, but clearly something’s happening beyond the frame of the picture (the world is happening beyond the frame of the picture – as are we, the viewer). As for a date; given the hats, I would say it was taken sometime in the 1920s.

The photograph is fragile. It has the feel of an Autumn leaf, dried and picked from the ground the following Spring. When I hold it in both my hands, my thumbs discover very slight depressions where others have looked before me. The way the paper’s warped, the way that it bends, tells me it’s been looked at many times.

Where the picture contains the trace of someone who was loved, the paper carries the gesture of the lover.

Of course we cannot know this, not for certain. But history is an act of imagination.

Who is the object of his or her attention? My eyes move to the girl at the front, dressed in white or pale colours and wearing a matching hat. My left thumb, in its slight depression almost seems to touch her, mimicking the gesture of the one to whom it belonged. There’s something secret about the image, as if whoever took it shouldn’t have been there, shouldn’t have possessed her. It’s an image that’s meant to be kissed, secreted away in a wallet. Affection has caused the wear in the corner.

She knows she’s being photographed. She knows that someone loves her. She can see in her mind’s eye the gallery behind. She can sense the gaze of her admirer. But then the paper tells me she didn’t turn around, she never returned the gaze. Ever.

Dust Motes

Echo

Last week I installed a temporary artwork in St. Giles, Oxford entitled Echo. The piece comprised approximately 200 photographs of individuals isolated from group shots of the fair taken in 1908, 1913 and 1914. The date of the exhibition, Wednesday 9th September was important in that it was the day after St. Giles’ Fair was taken down, and the ‘space’ left in its wake (the fair was up for two days and filled the entire street) helped frame the fact that all those people shown in the exhibition, who had once stood in the same street, had, like the fair, gone. I was interested in the boundary between existence and non-existence, the impossiblity – within the human mind – of death as nothing and forever. What I hoped the photographs conveyed was the importance of having been.

The installation required grass in order that I could place the markers in the ground and the War Memorial in St. Giles was the only viable option. What was particularly interesting was how the location altered the meaning of the work in that one couldn’t help identify the people with the memorial and in particular those who fell in World War One. Given that some of the men pictured in the photographs almost certainly went to war and may well have lost their lives, so the work took on a new and poignant dimension. Many of the women would have lost husbands, brothers, fathers, uncles and so on.

Click here to read more about this exhibition.

Same People

Having bought a copy of a photograph (St. Giles Fair, 1913) from the Oxfordshire County archives, I found when looking at the individual faces someone I recognised. Not someone I know or knew of course, but a lady I’d seen in another photograph.

The photograph on the left was taken on Headington Hill in 1903, and that on the right at St. Giles Fair in 1913. Below is another person I found in two different photographs, this time from 1908.

Ancestry

I’m very pleased to announce that my forthcoming exhibition, Mine the Mountain, will be sponsored by Ancestry.co.uk.

I have been researching my family tree for almost a year now and in that time have used Ancestry to search thousands of records (census returns; births, marriages and deaths etc.) to build what has now become quite an extensive tree with roots stretching back to the mid eighteenth century. And although most of this research has been carried out alone, through using the Ancestry website I have been able to join forces with a relative (a second cousin) who I have never met and who lives on the other side of the Atlantic in Canada. He had already made good progress on one line of my family (that of my maternal grandmother) and through the website, I was able to merge much of that information into my own research (and indeed, share with him my own first hand knowledge of people he’d never met).

Using the website I made very quick progress, discovering hundreds of people, some of whom had been completely forgotten, swallowed up by time and almost lost to the past altogether. And it was in response to this idea of the anonymous mass, that what had started as a hobby became an integral part of my artistic practice.

I have always been interested in history and the past was always going to feature in the work I wanted to make and much of my work over the last two years has stemmed from a visit I made to Auschwitz-Birkenau in October 2006.

As with many historical and indeed contemporary traumas (whether ‘man-made’ or natural disasters), one of the most difficult things to comprehend at Auschwitz (and indeed with the Holocaust as a whole) was not only the sheer brutality and inhumanity of the place, but the scale of the suffering experienced there. How can one possibly comprehend over 1 million victims (6 million in the Holocaust as a whole)? The only way I could even begin to try, was to find the individuals amongst the many dead; that’s not to say I looked for named individuals, but what it meant to be one.

One of the many strategies I used to explore the individual was that of researching my own past; not just that of my childhood, but a past in which I did not yet exist.

Using the Ancestry website I began to uncover names, lots of names which seemed to exist, disembodied in the ether of cyberspace like the names one reads on memorials (such as on the Menin Gate in Ypres), and I was reminded all the while I searched of a quote from Rainer Maria Rilke’s poem ‘The Duino Elegies,’ in which he writes that on dying we

“…leave even our name behind us as a child leaves off playing with a broken toy…”

It is interesting that in looking back on our lives and beyond, we inevitably pass through our own childhood, and indeed, I can remember mine replete with all its toys – a fair few of which were inevitably broken. In Rilke’s phrase above, we have an implied progression from childhood to adulthood and the fate that comes to all of us, but travelling back, we move away from death and think of our childhoods, remembering those toys which in our mind’s eye are always new, or at least, always mended. This sense of moving back and the idea of toys, or things, that are mended again, resonates for me with my research and my using the Ancestry website. One can think of the 800 million names stored in their databases as each being a broken toy, one that when it’s found again is slowly put back together.

Having discovered hundreds of names (or broken toys) in my own family tree, I’ve started to put the pieces back together, looking beyond the names to discover who these people were, and therefore, who I really am. And the more I discover, the more I find myself looking at history in an altogether different way. History is sometimes seen as being nothing but a list of dates, but like the names on Ancestry, there are of course a myriad number of things behind the letters and the numbers (the broken toy in the attic has been to places other than just the attic – and has been things other than just a toy).

Now when I think of an historical date, I relate that to my family tree and consider who was alive at the time. For example, when reading about the Great Exhibition of 1851, I know that at that time Richard Hedges, Ann Jordan, Elijah Noon, Charlotte White, William Lafford, Elizabeth Timbrill, John Stevens, Charles Shackleford, Mary Ann Jones among many others were all alive; what is for me a distant event described in books and early black and white photographs, was for them a lived moment whether or not they visited the exhibition itself.

When this photograph inside the exhibition hall was taken in 1851, they were a part of the moment, even when farming in Norfolk. When the guillotine fell upon Marie Antoinette on October 16th 1791 (I’ve just been reading about the French Revolution), Thomas Sarjeant, Ann Warfare Hope, David Barnes, Mary Burgess and William Deadman were going about their normal lives somewhere across the channel in England, and it’s by understanding their lives – of which I am of course a consequence and therefore a part, that I can begin to understand history as not some set, concrete thing that has happened, but something fluid, made of millions of moments which were at one time happening. Every second in history comprises these millions of moments when the world is seen at once by millions of pairs of eyes.

Therefore, as well as being a huge database of names, Ancestry can be seen as being a database of moments, the more of which we discover for ourselves, the greater our understanding of history becomes. This, in light of the project’s origins at Auschwitz-Birkenau, is particularly pertinent; the Holocaust, as a defined historical event, becomes millions of moments and the Holocaust itself not one single tragedy, but a single tragedy repeated six million times.

In effect, Ancestry allows users to map themselves onto history and the family tree becomes not just a network of relationships between hundreds of people but a kind of physical and geographic biography of the individual. Places we have heard of but never been to, places we have never known before become as much a part of our being as the place in which we were born and in which we live. For example, if there’s a place with which I can most identify physically or geographically, then that place would be Oxford, the town in which I was born, grew up and in which I live. Its streets which I have walked and its buildings which I have seen countless numbers of times, all hold memories – and what are we in the end but these.

Of course there are numerous other places which I have visited and which make me who I am (seaside towns in Dorset where I holidayed as a child for example) but as well as these places are those which, until I began my research, I had either never heard of or never visited: Hafodyrynys, Dorchester, Burton Dassett, Southam, Ampney St. Peter, Minety, Ampney Crucis, Cefn-y-Crib, Kingswood, Usk, Eastleach, Wisbech, Walpole St. Andrew and so on. Furthermore, places I had known and visited were shown to contain memories extending way beyond my own lifetime but of which I am nonetheless a part, or at least, a consequence. I have been to Brighton many times and have many memories of that place, but all the times I have been there, never did I realise how much it and the surrounding area had come to make me who I am.

So, as well as being a vast database of moments, Ancestry can be seen as an equally vast set of blueprints, each for a single individual – not only those who are living, but those who’ve passed away. And just as the dead, through the lives they led, have given life to those of us in the present, so we, living today can give life back to those who have all but been forgotten. Merleau-Ponty, in his ‘Phenomenology of Perception’, wrote:

“I am the absolute source, my existence does not stem from my antecedents, from my physical and social environment; instead it moves out towards them and sustains them.”

Of course our existence does indeed stem from our antecedents (and as we have seen, our physical environment), but what I like about this quote is the idea of our sustaining the existence of our ancestors in return. The natural, linear course of life from birth to death, from one generation to the next, younger generation, is reversed. Generations long since gone depend on us for life, as much as we have depended on them.

In his novel, ‘The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge,’ Rilke wrote the following:

“Is it possible that the whole history of the world has been misunderstood? Is it possible that the past is false, because one has always spoken of its masses just as though one were telling of a coming together of many human beings, instead of speaking of the individual around whom they stood because he was a stranger and was dying?”

This quote brings me back round to what I spoke of earlier; the idea that the past is made up of countless millions of moments – that History is not the concrete thing that has happened, but something more fluid, something which was once happening, and which, given Merleau-Ponty’s assertion above, is still happening, or at least being sustained. These moments are the world as seen by individuals. In Rilke’s quote, the history of the world, represented by the masses, has its back turned against us. We cannot see its face or faces, only the clothes that it wears. But the stranger in the middle, around whom history crowds is looking out towards us, and if we meet their gaze, we make a connection, we see the individual. And for a moment they might be a stranger, but through the dialogue which inevitably begins, we get to know them and the world to which they, and indeed, we, belong.

As I’ve said, Ancestry is more than a network of discovered (and undiscovered) relationships between hundreds of people; it’s also an immense collection of dialogues; one can imagine the lines which connect individuals as being like telephone wires carrying conversations between the past and the present. And the more one thinks of all these nodes and connections, the more one begins to see that Ancestry is also a metaphor for memory – after all, what are memories but maps in the brain, patterns of connections between millions of neurons which make a picture of what once was: history as it really is.

Mine the Mountain will run between 1st and 8th October 2008 in Oxford. Download a PDF for venues.

Shadows 2

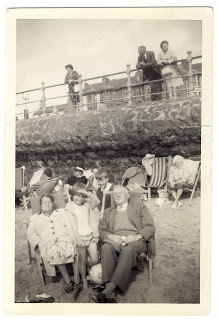

Recently I bought ‘The Book of Shadows’ (edited by Jefferey Fraenkel), which I found whilst browsing in Blackwell’s bookshop, a book of found photographs all of which contain the shadow of the photographer along with that which is photographed. It’s something in which I have been interested for some time with some of my own family photographs containing just such shadows.

It called to mind as I flicked through the pages, looking at photographs such as that below, the words of Austerlitz in W.G. Sebald’s book of the same name, in which the character Austerlitz states that fortifications:

“…cast the shadow of their own destruction before them, and are designed from the first with an eye to their later existence as ruins.”

In many respects, the same could be said of any building or even, individuals. We all cast the shadow of our own mortlity before us, and, in respect of what Barthes has written in Camera Lucida (“I observe with horror an anterior future of which death is the stake… I shudder… over a catastrophe which has already occurred. Whether or not the subject is already dead, every photograph is this catastrophe.”) these shadows in these pictures could be said to be just that.

Below is one of the images from the book. There is something poetic about this image in particular, in the way the train tracks lead us to the distance, to the future, almost as if they are there to transport this shadow of the photographer’s own ‘destruction’.

Below is one from my own collection showing my grandfather, my aunt and my mother.

Umbilical Light II

I started working on the project today using some VJ Sofware called Resolume which allows for comprehensive realtime effects changes etc. using MIDI and received audio signals. Parameters of effects such as blurring (which I have used in this project) can be determined by the frequency range of the received audio signal which means one can get some very nice results quite quickly.

I started by using details of photographs which I’d scanned from a book of old Oxford photographs. The published images are not so great so the details are even less so, but nevertheless this added somewhat to the progression of the work.

What I couldn’t help but see when I was working on the piece, using all manner of synths to make the desired noise (which I haven’t quite achieved as yet) was how the photographs when manipulated in this way became x-ray photographs of internal organs which, given the title of the projects seemed very apt.

The following photographs are the three main images I used:

Taken in what is now South Park in 1903

Taken in Queen Street c1900

Taken in St. Clements c1910

The following are stills created using synthesizers (my old Roland XP60 as well as Reaktor and Absytnth) and Resolume.

For me, the image looked like a heart and when I manipualted the video using a basic bass drum pattern, it really worked. Below is a video file showing a part of the work – unfortunately without the sound.

Umbilical Light

In ‘Camera Lucida,’ Roland Barthes asks whether history is not simply that time when we were not born? He writes:

“I could read my non-existence in the clothes my mother had worn before I can remember her.”

The study of history necessitates the consideration of our own non-existence. To imagine a past event, as it was before our birth, requires us to see that event without knowledge of what was to come, much as how we don’t know what is coming tomorrow. But to imagine our non-existence, our being not-yet-born, becomes in our conscious minds nothing less than the image of death; such is why perhaps we struggle to comprehend the past, to look upon a turn of the century photograph, where our coming-into-being is so precarious.

Looking at photographs of Oxford, taken around the beginning of the 20th century (such as that below taken in Cornmarket in 1907), I can’t help imagine that somehow, amongst the numbers pictured, are some of my ancestors, or, failing that, someone they at least knew. Perhaps there might be someone unknown to them, who nevertheless crossed their path and in some small way (or, in the case of my own coming-into-being, no small way) made an impact on their life and indeed on all those to come.

But then of course, by thinking this, I am doing just what I shouldn’t do when trying to properly understand this image or rather this moment in time. I am placing upon it the weight of future history. But when I recognise the buildings in the picture, how can I take myself ‘out of the frame’ altogether? Is it not impossible?

Is history then not simply the study of the past, but rather the study of how we got here today? A study of pathways, intersections and the spaces in between – a form of cartography? Well, it is and it isn’t. To study an event we must discover what really happened, and what could have happened if things had been different, what might its protagonists have done otherwise? History therefore – through these other possible outcomes – requires us to examine our own fragility, our unlikely selves and the possibility of our never being born to ask the questions at all.

At the moment the photograph above was taken, when all those pictured were going about the business of their lives, the chance of my Being was practically nil. Now, as I look at the photograph I know that everyone pictured is dead; I can read my own non-existence in the clothes they are wearing, just as they might have read theirs in the photograph itself. But here we have a difference between not-Being and being dead and the photograph is an illustration of that very thing.

Susan Sontag wrote:

“From a real body, which was there, proceed radiations which ultimately touch me, who am here; the duration of the transmission is insignificant; the photograph of the missing being as Sontag says, will touch me like the delayed rays of a star. A sort of umbilical cord links the body of the photographed thing to my gaze – light though impalpable, is here a carnal medium, a skin I share with anyone who has been photographed.”

When we look at a star in the night sky, we can be assured that in most cases, the light which hits our eye, is at least hundreds of years old. It might even be that the star no longer exists, yet we can be certain that it did exist. The same can be said of those we see in the photograph; somehow the light as Sontag writes is like the delayed rays of a star – an umbilical cord which links us with them and vice-versa (if any of those pictured are indeed my ancestors, then the metaphor becomes more vivid). The moment the light left them (and the star), we did not exist; the moment we received it, they did not exist, and yet here we both are and here we have been.

This umbilical light, which springs from each of us, links us to our own non-existence. History is indeed a study of pathways, intersections and the spaces inbetween, and these pathways are made of light.

Young Werther

Whilst showing my tutor some of my research regarding photographs found in Auschwitz, she pointed out that on the reverse of one of them was a quote regarding Goethe.

The following photograph was taken in Bedzin in Poland in the 1930s.

The book from which this image was taken, states that it is a picture of: “Moniek Szwajcer (right) in front of the ruins in Bedzin. Dedicated possibly to Zygmunt Sztrochlic and Sabka Konińska.” And inscribed on the back in Polish were the words: “For my dear Zygmunt and lovely Sabka, in commemoration of beautiful years of work together at the school. From ‘Young Werther’, Moniek. Bedzin, 29 October 1937.

Young Werther refers to the book ‘The Sorrows of Young Werther,” by Goethe, which as a result of re-visiting this photograph, I have bought.

Herodotus and the Morning Paper

One has to remove the future from a past event to really understand its ‘presentness’. One has to view historical (‘Herodotus’ – see Walter Benjamin and Objects) events as being on the periphery, whilst the mean and the commonplace (‘morning paper’) take centre stage. It is the distance which interests me, the distance from the heroic or ‘main’ event and the historical perspective this gives us.

“Thus the whole emerges simultaneously with the accumulation of the parts, not because it is the sum of the parts, but because it is immanent within them.”

Bortoft’s theory of authentic wholeness could be applied to history. A great event, such as a coronation (let’s say, that of Elizabeth I), is not a whole in itself. Step outside the ceremony, outside the city and into the countryside; walk into a tavern… what is happening there, at the exact moment of the coronation? Let’s say a man sits at a table eating his dinner, enjoying a drink. The moment of the coronation is not simply about the ceremony but the moment in time (some time on January 15, 1559); that moment, of which the Queen and the man in the house are equal parts, although history has forgotten one and kept alive the other. Within both these people (parts), the moment (the whole) is immanent.

The man in the tavern pours his wine from a jug; 450 years later and that jug is in a display case in a museum, freed as Benjamin would have it from the ‘drudgery of its usefulness.’ For us to see it properly as it stands behind the glass, we need to re-impose that drudgery, we need to see it as it was, when it was useful.

Returning to the idea of distance and perspective: the distant elements in my old holiday photographs on which I have been doing some work, as well as those in old photographs (windows and bicycles) coincide to some degree with what I have written above. When I look at a photograph, taken during a family holiday in the late 1970s, I see the people I recognise, whether that’s myself, my brother, parents or grandparents. But there are often others, all of whom were a part of that moment (such as the girl below who was standing in the distance of one of our snaps).

Returning to objects: how do we re-impose the ‘drudgery of an object’s usefulness’ back onto the object? Think of the old musical instruments in the museum. How did I give it back its usefulness? By using the Goethean method of observing, and, in particular, by placing it back – through use of the imagination – in its own time. Although I wasn’t looking at the specific ‘gesture’ of things at that time, I believe I found the gesture of the lira di braccio nonetheless.

So, returning to the man in the tavern; what are the elements of that place which one would need to understand in order to re-construct it through the imagination? Objects (contemporary and old), environments (the room itself and elements thereof), conversations…

Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century

On the first day of this month, I travelled to Paris on Eurostar and met my girlfriend Monika at the Gare de Nord station, she having travelled in from Luxembourg by TGV to Gare de l’Est. I was last in Paris in 1992/93 (the exact date eludes me) on a visit made as part of my degree in Art History, and although my memories of the city were rather vague and (before re-visiting) few, my impression of it was nonetheless intact and fairly lucid. From the pretend statue at Sacre Coeur (a woman, painted white, standing still), to being lost somewhere near Les Halles, from the pastels of Odilon Redon in the Musee D’Orsay, to Rodin’s ‘Balzac’, from the Musee Moreau to a few trips made on the Metro, I could adduce that Paris was beautiful, and, as Walter Benjamin described it in his Arcades Project, the ‘Capital of the Nineteenth Century.’

This sense of it being a nineteenth century city might owe as much to the fact that much of it was indeed built (or rebuilt) in that period (with the extensive renovations by Haussmann in the 1860s) and that its ‘symbol’ the Eiffel Tower, was constructed between 1887-89 as the entrance arch for the Exposition Universelle (the novelist Guy de Maupassant, who claimed to hate the tower, supposedly ate lunch at the tower’s restaurant every day. When asked why, he answered that it was the one place in Paris where you couldn’t see it).

The city’s character is formed as much by an abundance of 19th century literature (Zola, Baudelaire, Balzac, Huysmans…) and art (Realism, Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Symbolism…) than simply ‘bricks and mortar’, yet, despite this sense, it’s by no means a city stuck in the past at all, rather it’s very much of the present, as if the intervening time had not intervened, as if there was nothing to intervene between.

November the 1st is All Saints Day, and by tradition, people in many European countries, including France, take flowers to the graves of dead relatives. Our hotel room, overlooked the cemetery at Montmartre which, having unpacked, we visited.

For Monika, being Polish, the day was very much part of her own tradition, and one of the first things we saw as we walked around, was a group of Poles reciting a prayer for a fellow countryman laid to rest in the cemetery. The cemetery itself was interesting inasmuch as it was very much a part of the city, rather than a place divorced from life – a sense augmented by the bridge which ran above it, beneath which the tombs of the dead resembled makeshift dwellings erected by the homeless; constructions for the purpose of temporary habitation, rather than eternal rest. Indeed, given the occasional broken pane of glass we wondered whether or not they were in fact used as shelters; where the living tap the dead for respite from life.

These little dwellings were beautiful, especially where time, which ought to have let the dead alone, had scratched away at the doors, much like the vagrants seeking shelter from the rain.

The first grave we saw took my interest, since a cat was laying on top of it, dead centre, looking towards the headstone. I took a photograph (which I have since, accidentally deleted) and immediately, a lady, standing with a man (I presume was her husband) asked me in French, ‘why did you take a picture?’ I must confess here that I do not speak French and relied on Monika who does. I explained that I was interested in the cat and was amazed then to discover that the grave was that of her mother. Suddenly, from an anonymous grave with an anonymous name, the memorial had come to mean much more. There was a physical, living connection. She explained in polite conversation, that the cat had been there most of the day and hadn’t moved even when she busied herself about the grave arranging flowers and so on. Cats, we were to discover, were a common feature of the cemetery.

One sculpted tomb was especially beautiful. It showed what I presume to be the deceased, not as he was whilst living, but as he was dead. His sunken features, his closed eyes, and the exposed shoulder all pointed to something deeper than sleep. The eyes in particular were striking, in that one could see they were the eyes of a man who would never open them again. The shroud had been pulled back, to allow one last look at his face, a look which had lasted over a century. I say, as he was dead, but of course he still is dead, and this sculpture serves in a way to remind us, that even in death we are not free from ‘time’s relentless melt’.

On our second day in Paris, we visited the Louvre which, I remembered, I hadn’t visited during my first stay in the city. The building is indeed impressive, as are the queues which inevitably form outside. Nevertheless, having joined the queue outside we soon found our way to the queue inside which as well as being much longer was even slower to move. In fact, it took almost an hour to get a ticket which wasn’t surprising considering that one of the two tills serving our queue was closed and when that which was closed finally opened, the open one, for the purposes of consistency, closed, and this fat caterpillar of people continued chewing on its incredulity.

Once in, I found the Louvre to be almost worth the wait, although the queue had sapped our strength somewhat, and what one needs when walking around the palace is all the strength one can muster; mental as well as physical. What did strike me was the bizarre behaviour of most of the other visitors, something which I remembered as having struck me when I visited what I think was the Grand Palais during my first visit. Back then, a number of people walked around the galleries videoing continuously, looking at everything through the eyepiece of a video-camera, and now, in this increasingly digital age, the same is true but on a much larger scale. Maybe it is something to do with our contemporary culture which means we cannot see something unless it’s reproduced, we cannot know it except through facsimile, that things are not received as being experienced unless captured by a camera. Imagine, you’re approaching a painting, a genuine da Vinci (not the Mona Lisa in this instance). You are about to see something which you know the great man saw himself, something with a provenance dating back over five centuries, an image which countless numbers have looked at since its creation. What do you do? Well, the woman in front of us framed it in her camera, took its picture and walked off looking at the image on her camera’s display. The difference between something original and a copy (and by copy I mean a skewed, 5 megapixel digital photograph) has, it seems, been attenuated to such an extent that there’s no longer any perceived difference at all.

Near to where this ‘incident’ took place is the room which houses the Mona Lisa, a painting whose popularity is, in part, due to the viral-like profusion of its myriad reproductions. On posters, postcards, badges, T-shirts, calendars, mugs and so on, the image is better known than any other in the world, and so, as if she were a celebrity, people crowd about her – as she gazes out from behind her bullet-proof screen – all wanting a copy of their own. Phones are raised amidst the clamorous throng like numerous periscopes; cameras snap at her heels. It really beggars belief.

There were no throngs of people slobbering around Holbein’s portrait of Erasmus, or Vermeer’s Astronomer, and there was no-one standing in front of Ingres sublime portrait of Louis Francois Bertin, a painting which at 116 x 95cm, is, if not in scale, truly epic. Bertin looks out from across almost two hundred years, as alive as he was then. He looks at you as you dare to return his dismissive gaze. One can almost hear him scoff. You are mortal. You can almost hear him say it. He is immortal and you know that he is thinking it. He looks right through you at the centuries to come when you will be long gone from his gaze. “I will still be here,” he says. It really is one of the great portraits.

An artist well known for his monumental works, Anselm Kiefer, was at the time of our visit exhibiting three new works commissioned by the Louvre. It took us a while to find them, and when we did I must say I was rather disappointed. Whereas Ingres more modest-sized portrait was made vast in the palace, Kiefer’s painting ‘Athanor’ despite its scale was rendered rather small. The two sculptures either side were somewhat peripheral and reminded me of Christmas trees which after New Year start to outstay their welcome. This is not to say that any of these works are bad, they’re not – far from it. But somehow in this setting they just didn’t seem to work.

After the Louvre, we were given a guided tour by one of Monika’s friends of the Marais district, which was a real treat. The Marais district (meaning marsh or swamp), spreads across the 3rd and 4th arrondissements on the Rive Droit, or Right Bank of the Seine. According to one of the many websites on The Marais, it was:

“… in fact a swamp until the 13th century; when it was converted for agricultural use. In the early 1600s, Henry IV built the Place des Vosges, turning the area into the Paris’s most fashionable residential district and attracting wealthy aristocrats who erected luxurious but discreet hotels particuliers (private mansions). When the aristocracy moved to Versailles and Faubourg Saint Germain during the late 17th and 18th centuries, the Marais and its mansions passed into the hands of ordinary Parisians. Today, the Marais is one of the few neighborhoods of Paris that still has almost all of its pre-Revolutionary architecture. In recent years the area has become trendy, but it’s still home to a long-established Jewish community.”

Evidence of the Jewish community, and, in particular, the traumas suffered at the hands of the Nazis and the Vichy government can be found in the Holocaust Memorial, as well as the memorial in the Alle des Justes, dedicated to all those who helped the Jews in such dangerous and terrible times; thousands of anonymous names (unknown at least to visitors) who nevertheless did so much, to do good in a very bleak world.

On numerous walls of various buildings were plaques dedicated to the hundreds of children deported from the district’s schools. Having visited some of the terrible places where some of these children ended up, it’s somehow even more distressing to see the place from where they were taken.

Evidence of the area’s mediaeval past can be seen in its surviving ancient wall, the only section left of the Philippe Auguste fortifications which date back to the 11th and 12th centuries. It’s just one of the many features which distinguishes this part of Paris from the rest of Benjamin’s ‘Capital of the Nineteenth Century’.

But it’s more than just the old buildings, the place has a character which is quite unique; it’s quite understated (although not entirely); most unlike the sweeping brovado of Haussmann’s boulevards. In one part of Marais, there is a group of antique shops, called Village St. Paul, where we came across a photographic shop selling old photographs. This shop, called ‘Des Photographies’ was a place in which I could have spent several hours sifting through snapshots of times long gone, and although we were pushed for time, we did purchase two photographs, or rather one and a half, for one of the photos had been cut from a bigger picture.

The first shows a young woman, standing in the rain. I cannot tell exactly when it was taken, but I would imagine it’s some time in the 1920s or 30s.

I liked this for the fact it had been cut from a bigger photograph. But why was it cut? Was it malicious? Was it through heartbreak? Was someone cutting this woman, this memory, from their life? Of course it could have been anything but malicious.

The second photograph, which Monika bought for me, is a group portrait, perhaps a family, taken around the end of the nineteenth century.

This photograph is interesting for many reasons, one being that no-one is looking in the same direction. Only one person, the woman standing behind the old lady (seated) is looking at the camera. The photograph itself, judging from the back, had at one point been part of an album, and one can’t help wonder when looking at it what other pictures accompanied it within that collection. Individual portraits of those within the picture perhaps? Images of where they came from? Who were these people, these men and women who have since lost their names? It’s strange, but sometimes names outlive the body (on plaques and tombstones) or bodies (or at least their alchemical equivalents) outlive the names (such as with these photographs), but rarely do the two continue to coexist.

The following morning we made our way to the largest and most famous cemetery in the city, Pere Lachaise. The cemetery takes its name from Pere François de la Chaise (1624-1709), confessor to Louis XIV, and is reputed to be the world’s most visited cemetery, not that it seemed particularly busy as we walked around. Armed with a map upon which we’d marked the graves we wanted to see, we spent a few hours wandering through the streets and avenues of this vast necropolis.

Among the graves we visisted were those of, Apollinaire, Balzac, Sarah Bernhardt, Bizet, Gustave Caillebote, Chopin, Corot, Daumier, David, Delacroix, Paul Eluard, Gericault, Ingres, Moliere, Piaf, Pissarro, Proust, Seurat, Gertrude Stein and Oscar Wilde.

Theodore Gericault (1791-1824)

Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot (1796-1875)

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780-1867)

And there was something quite strange about seeing the graves of painters whose works we had seen in the Louvre the previous day, artists such as Ingres, who’d given Louis Francois Bertin immortality through his portrait. It was hard to reconcile the fact the he – Ingres – had been dead and buried in this place for 140 years, over a hundred years before I was even born, whilst fresh in my memory was an image which would have once occupied a space in his own: the intervening time had not, as I said earlier, intervened at all.

As with the cemetery at Montmartre, what I found myself drawn to were the graves of those who’ve not left behind a tangible heritage (paintings, discoveries, books etc.). Those names without bodies; scratched like grafitti, by a vagrant time who wanders amongst the stacked sepulchres. Names which do not ring bells when you read them, into whose shapes the moss has grown; names around which death has become less eternal; fragile like glass, broken in the bent and buckled leading of once replete windows.

In broken windows such as these, we see the passing, not just of a life, but of memories; the passing of those who came after the deceased with whom the increasingly vague memories of a distant relative melt into further graves. In every cemetery, you will find hundreds, maybe thousands of anonymous names; names and numbers from which we are separated by generations, decades or even centuries, and of course the ultimate experience: death. And in a cemetery, perhaps somewhere in France, are the names of those people in the photographs I bought in Le Marais; the single woman cut from the bigger picture (in more ways than one), the old lady seated on a chair in the sunlit garden, the two women beside her, and the three men all looking in different directions.

Having said goodbye to Monika at Gare de l’Est, I listened to ‘In Our Time’, a podcast from the BBC. The episode I was listening to was on the 17th century philosopher Spinoza, whose work George Eliot had translated in the 19th century, and whilst discussing Eliot’s epic novel Middlemarch, one of the speakers paraphrased an extract from its conclusion, an extract which I have since discovered, just as she had written it:

“But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.”

What we leave behind (our legacy) is not justified solely by its apparent value or greatness; whether or not it’s great art or literature, or a discovery which will prove a catalyst for even greater advances. It is not dependent on whether or not we have made some kind of sacrifice or acted with courage in times of great affliction. It is also those unhistoric acts of which Eliot speaks, by people who in many cases are not even names anymore. It’s often the decidely average which plays the greater part. Everything, even the mundane has an influence on the world.

In the translator’s forward to Walter Benjamin’s even more epic Arcades Project, Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin write of Bejmain’s intentions as being:

“to grasp such diverse material under the general category of Urgeschichte, signifying the ‘primal history’ of the nineteenth century. This was something that could be realized only indirectly, through ‘cunning’: it was not the great men and celebrated events of traditional historiography but rather the ‘refuse’ and ‘detritus’ of history, the half concealed, variegated traces of the daily life of ‘the collective,’ that was to be the object of study, and with the aid of methods more akin – above all, in their dependence of chance – to the methods of the nineteenth-century collector of antiquities and curiosities, or indeed to the methods of the nineteenth-century ragpicker, than to those of the modern historian.”

Paris is indeed the capital of the nineteenth century, but what of the nineteenth century itself? As the French philosopher Henri Bergson wrote, who is himself commemorated in the Pantheon:

“There will no longer be any more reason to say that the past effaces itself as soon as it’s perceived, than there is to suppose that individual objects cease to exist when we cease to perceive them.”

Somewhere, the century still exists and Paris is still its capital.

Parisian Cemeteries

Whilst on a trip to Paris with Monika, we paid a visit to two cemeteries; one, the cemetery at Montmartre, near our hotel, and the other, the famous Pere Lachaise cemetery in the east of the city. The cemetery at Montmartre was interesting in the way it was very much a part of the city, rather than a place divorced from life. This feeling was enhanced by the bridge which ran above it, beneath which the tombs of the dead reminded me of the makeshift dwellings put up by the homeless.

The first grave we saw took my interest, since a cat was laying on to of it, dead centre, looking towards the headstone. I took a photograph (which I have since, accidentally deleted) and immediately, a lady, standing with a man (I presume was her husband) asked me in French, ‘why did you take a picture?’ I must confess here that I do not speak French and relied on Monika who does. I explained that I was interested in the cat and was amazed to discover that the grave was that of her mother. Suddenly, from an anonymous grave with an anonymous name, the memorial had come to mean much more. There was a physical, living connection. She explained in polite conversation, that the cat had been there most of the day and hadn’t moved even when she busied herself about the grave arranging flowers and so on. Cats, we were to discover, were a common feature of the cemetery.

The day we visited was November 1st, a public holiday and the Day of the Dead, a time in some European countries when people visit the graves of loved ones. I knew, through Monika, that it was an important time in Poland, and, sure enough, where there were Polish graves in the cemetery, there were Poles, laying flowers, saying prayers, and remembering those of their country who had long since died; a tradition which is both poignant and to be admired. Later, when we visited Pere Lachaise, we found the grave of Chopin bedecked with flowers and a sashes of the Polish colours.

Some of the graves in the Montmartre Cemetery were particularly beautiful. Many were like tiny dwellings replete with doors and windows (usually stained glass), and although many had decayed through the ravages of time, their wearied state accentuated the romantacism inherent in many such cemeteries.

One sculpted tomb was particularly beautiful. It showed what I presume to be the deceased, not as he was whilst living, but as he was dead. His sunken features, his closed eyes, and the exposed shoulder all pointed to something deeper than sleep. The eyes in particular were striking, in that one could see they were the eyes of a man who would never open them again. The shroud had been pulled back, to allow one last look at his face, a look which had lasted over a century. I say, as he was dead, but of course he still is dead, and this sculpture serves in a way to remind us, that even in death we are not free from ‘time’s relentless melt’.

At Pere Lachaise, I was keen to visit the graves of artists, writers and composers such as Ingres, Moliere, Pissarro, Proust, Chopin, Gericault, Delacroix and Wilde amongst many others and having bought a map of the cemetery (which is vast) Monika and I planned our visit and began to seek them out.

It was strange – in the case of the various painters buried there – that having seen their work in the Louvre, we were now standing above their remains. One painting, for example, which we had seen in the Louvre, stuck in my mind as I stood next to the grave of Ingres (1780-1867). It was his portrait, painted in 1832, of Louis Francois Bertin, one of the most famous works by the artist, and one which is so full of life, it hardly seemed possible that the man in the painting and the man who painted it were long since dead. How was it, that I had seen something I know Ingres had also (obviously) seen, yet here I was, standing above his grave where he had lay for over a century before I was even born. That is the power of painting; they are objects into which the artist paints him or herself, in brushstrokes (particularly in the case of the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works we saw) which made in moment can exist for all time.

On the way home from Paris, as I passed beneath the sea in the channel tunnel, I began to write about the visit to Pere Lachaise. What I had been aware of as we walked around, was the content of the photographs I was taking, some of which follow:

They were all images of decay, the gradual fall into disrepair of the numerous memorials in this vast necropolis, and, given the work I have lately been doing on the ‘gestures’ of things, I began to consider the ‘gesture’ of this particular cemetery. What follows is what I wrote on the way home:

(The gesture is) like mould, lichen, which grows slowly in small patches over a long period of time. But these spores are invisible, we cannot see them except in the broken panes of glass, the flaked paint, the verdigris patinas on the doors to individual tombs, the chipped stones; every trace of time’s slow, considered vandalism. It’s always present in the cemetery and every now and then, one detects a trace of its fleeting presence – the scent of vinegar which lingers around a tomb where the glass is missing, where the door is open, or where the iron gates have corroded and been worn through by time’s relentless scratching; time’s relentlessness.

Even when all trace of the bones has gone, long after the burial clothes and the casket, time will continue its malevolence, picking at the fabric of memory, wearing down the words, smoothing over names, dismantling the dead and our memories of them, withering through slow alchemy these parts into atoms. Candles lit and placed beside the graves will soon be extinguished, flowers will be wilted, trees will be naked, picked of their leaves and left like confetti, to remind the living of this withering certainty.

Cemeteries are not just places where the dead are dismantled, where the names by which these parts were held together are also broken apart. They are as much for the living, who fight with death to keep the parts together, to deny death, to deny its certainty; to deny their own futures. The living wander the graves to maintain the present. Inside cemeteries the present is stretched.

We walk through cemeteries, and with our minds like nets try and catch this butterfly called Time, but we are assailed by its beauty, we stand open-mouthed and wait for the crysalis to be spun with invisible thread around us.”

Cemeteries have something in common with old photographs, particularly when we consider the the writing of Roland Barthes who writes that photographs have within them the ‘catastrophe of death,’ and that, ‘in the photograph, Time’s immobilisation assumes only an excessive, monstrous mode: Time is engorged…’. In cemeteries too, Time is somehow engorged and obviously contains – in abundance – that catastophe. One has the impression of time standing still, stopped by the dates of death carved into the many gravestones and tombs, yet we know, all too well, that time continues…

Printmaking – A Reflection III

Yesterday I carried on with the process I initiated two weeks ago, that of burying an engraved plate, leaving it a week and then printing the rusted version. Having dug up the plate after a second period in the ground, I was pleased with the resulting pattern of rust which I hoped would be lifted onto the paper by some of the ink during the printing process.

The resulting print from this plate was as follows.

The thing I realised with printing from such a rusted plate was the fact that the rust has quite a pull on the ink, and so once the paper has been through the press and one lifts it from the plate, it has a tendency to be left behind. With the print above, I was somewhat disappointed that the rust was ‘drowned out’ by the ink – hardly surprising when I think how thickly it was applied. Of course this is normal, but whereas one can use the scrim to take the ink off, and use quite a bit of pressure to do so, with the rust one doesn’t want to rub so much (and thereby remove it) and so the ink remains too thick in these areas.

I took a second print of the plate without re-inking and and the texture of the rust was well preserved.

For the next print (after a third week in the ground the plate will be even rustier) I need to ink the particularly rusted sections less and perhaps moisten the rust to encourage it to lift off the plate.

As well as continuing this experiment, I also started working with photo-polymer plates. A photograph is printed onto acetate (with all black areas ‘removed’/greyed) and this positive is then used to ‘etch’ the plate. The plate is sensitive to UV light and so this is done in a darkroom in a UV box. The light passes through the acetate and exposes the plate in the darker areas. When the plate is washed and inked, these areas then take the ink which is then printed onto the page.

In order to get a good print, one needs to make two or three proofs, the results of which are below (those on the left being the first).

The question I have to ask myself now is what does it mean to print these photographs as etchings? Something to consider over the next few days.

A Rocking Horse at Starbucks

Whilst writing on old photographs, I came across several pictures of Oxford, taken for the most part just after the turn of the twentieth century. One of them, a view of Cornmarket in 1907 is reproduced below.

This photograph is interesting for a number of reasons (you can read more on this and other photographs here), the clothes – particularly those worn by the women – and the rather rudimentary means of transport, all point to a time long since gone. But what really took my interest, over and above everything else, was the rocking horse in the window on the right hand side of the image (see detail below).

The following is taken from my my writing on old photographs of Oxford:

“…rather sentimentally perhaps, I was drawn to the rocking horse in the window. One can’t help but wonder what happened to this somewhat peripheral object (peripheral in terms of the overall photograph). I can well imagine it languishing in some dusty attic, forgotten, broken… although, of course it might be in very rude health, respected as an old family heirloom. And herein lies it’s point of interest. Whatever its current state – if indeed it still exists – here, in the picture, it’s yet to occupy the mind of the person to whom it belonged. It’s yet to form the memories which that person would carry with them throughout their life, memories which they might have passed down and which might, to this day be talked about. Perhaps this rocking horse no longer exists as a physical object, but maybe somewhere, it continues to move in words, written or spoken.”

I knew the window in which the rocking horse stood 100 years ago still existed, although now, sitting behind the glass, in place of the horse, were people drinking coffee in one one the city’s Starbucks.

Comparing the image above taken in 2007 with that taken in 1907, it’s clear that in the intervening 100 years there have been – obviously – many changes – not least the fact that everyone in the 1907 photograph is dead (Barthes’ ‘Catastrophe’). Also, there have been many changes regarding the street’s physical appearance – several of the buildings have been demolished and replaced, in many cases, not for the better (the concrete block on the corner of Market Street).

Looking beyond the photographs, at the wider world, I looked up a list of inventions and discoveries of the 20th century, to get more of an idea as to what else has changed. Most of course were obvious, but the list ran roughly as follows:

instant coffee

talking pictures

the crossword puzzle

the bra

the pop-up toaster

frozen-food

TV

the aerosol spray

penicillin

bubble-gum

the jet-engine

the computer

the polaroid

cats eyes

canned beer

nylon

radar

the photocopier

the ballpoint pen

the helicopter

the slinky

the atom-bomb

the microwave oven

the Frisbee

Velcro

the credit-card

the non-stick pan

McDonalds (which stands today in this very street – in fact, I took the photograph just outside)

the Barbie Doll

audio-cassettes

felt-tips

the ATM

LCD

VCR

the CD

the post-it note

the ink-jet printer

mobile phones

Apple

Windows

Prozac

the internet…

It’s the small things in this list (e.g. the pop-up toaster and post-it notes) as well as the large (jet-engines, the internet) which particulary interest me; small things, but things which have nevertheless helped shape our world today; the way we think and the way we live our lives. It’s hard to imagine a world without the pop-up toaster, ball-point pens and frozen food, but there it is in the photograph.

I first became interested in the importance of small objects on a residency at OVADA, making a series of walks around the city, on which I would note down anything that took my interest, no matter how small and seemingly irrelevant. Below is an extract from a talk I gave as part of the residency.

“The chances of any of us being who we are is practically nil. In order for me to be born, I had to be conceived at the exact time I was conceived, any difference in time – even a split second – and I wouldn’t be me. Also, everything leading up to that moment had to be exactly as it was; anything done differently by my parents, no matter how small, how seemingly irrelevant, any deviation from the path and I would not be me.”

Any of these smaller objects have the power to alter the path of our lives and as such the future. In 1907, the rocking horse in the window might have caught the attention of a passer-by, enough at least to alter his or her life’s path just for a second, and subsequently, in some small or signficant way, the future. I wonder – if I was walking around the city of 1907, listing things as I did on the residency, whether I would have written down, ‘Rocking Horse in a window’.

This future world has seen enormous changes. The world in 1907, of which that street was a part, is in many respects a completely different place to the world of 2007 (not least because of two world wars, the Holocaust, and countless other wars and atrocities). Yet, the two photographs, or at least the first photograph and my contemporary knowledge of the street, share similarities – they are recognisable as being one of the same thing. In both photographs, the tower of St. Michael at the Northgate can be seen in the distance, standing where it has stood since c.1050.

In fact, despite the wholsesale change in the population and the changes to a number of the street’s buildings, the most striking difference for me, is the absence of the rocking horse. So much about the turn of the twentieth century seems to be expressed by it standing in the window, and so much about the years in between, articulated by its disappearance.

From Dinosaurs to Human Beings

After yesterday’s viewing, I began to think about the works I’ve produced so far on this residency and what it is that links them; not that there should be a link – I just know that there is one. Despite the differences, there is an underlying theme which unites the drawings, the text pieces, the deckchairs and the paintings. So what is it?

In answering this I have started to think about… dinosaurs. Not something which first springs to mind when looking at my work and if I mention Jurassic Park, then it might seem that I’m losing the plot altogether, but there is a sequence in this film which is relevant to my work.

In the film, the visitors to the Park are shown an animated film, which explains how the Park’s scientists created the dinosaurs. DNA, they explain, is extracted from mosquitoes trapped in amber and where there are gaps in the code sequence, so the gaps are filled with the DNA of frogs; the past is in effect brought back to life with fragments of the past and parts of the modern, living world. This ‘filling in the gaps’ is exactly what I have done throughout my life when trying to imagine the past, particularly the past of the city in which I live.

As well as reading about and drawing dinosaurs, I also as a child, liked to create and map worlds; countries which I would build from fragments of the world around me; forests, mountains and plains – unspoilt landscapes. And in these worlds there would exist towns and cities, created from ‘the best bits’ of those I had visited.

These invented worlds became, as I grew up, the ‘invented’ or imagined landscapes of Oxford’s past; landscapes that were – just as they still are – created from fragments, parts of the past which are still extant in the city; old buildings, walls, objects and so on. Between these structures, these fragments, I would fill the gaps, with my own imagination, with thoughts derived from my own experience. The city’s past and the past in general, as it exists within my mind, is then, to use the metaphor of cloning in Jurassic Park, a cloned dinosaur. The extant buildings, structures and objects within museums, are like the mosquitoes trapped inside the amber. They are broken strands of DNA. All that is required is for me to fill the gaps, and this I can do with my own DNA. I am in effect, the frog.

This metaphor is interesting in that DNA patterns are, of course, unique to everyone. My DNA is different to everybody else’s as there’s is to mine. Therefore, using my imagination to plug in the gaps of the past, means that the ‘past’ will comprise large parts of my own experience; my dinosaur will contain elements of my own being. (See ‘Postcard 1906’). But although my DNA is unique, it is nonetheless derived from my own past, elements have been passed down by my ancestors from time immemorial. The code which makes me who I am, comprises parts of people I know now (parents and grandmothers), people I knew (grandfathers and great-grandmother) and people lost to the past altogether (great-great grandparents and so on). What interests me about this, is that, through stating above how ‘my dinosaur will contain elements of my own being’ I can now see that ‘my dinosaur’ will contain elements of my own being, which is itself comprised of elements of hundreds – thousands – of people, the majority of whom I will of course never know and who have been dead for centuries. I like to think therefore, that ‘my dinosaur’ and my imagination aren’t entirely unique.

This leads me to look at paths – not the route I walk around the castle, or those recorded by my GPS receiver (although these are entirely relevant) but to the paths taken by my ancestors so that I might be brought into being. The chances of any of us being who we are is practically nil. In order for me to be born, I had to be conceived at the exact time I was conceived, any difference in time – even a split second – and I wouldn’t be me. Also, everything leading up to that moment had to be exactly as it was; anything done differently by my parents, no matter how small, how seemingly irrelevant, any deviation from the path and I would not be me. This is extraordinary enough (whenever I see old photographs of members of my family, I think that if it was taken a second sooner or later, I would not be here) but when one considers this is the same for my entire family tree, again, all the way back to time immemorial, then one realises how, to quote Eric Idle in ‘Monty Python’s Meaning of Life’, ‘incredibly unlikely is your [my] birth’. We are all impossibly unlikely. The chances of all our ancestors walking the exact paths through their lives which they walked is almost nil.

Therefore, my walks, my mapping, my identifying (seemingly irrelevant) objects, my recording them, my palimpsests, are all linked. Memorialising objects (disposable or otherwise), snatches of conversation and so on, inscribing them on a slab, shows how vital these fragments are to future generations and to me in terms of my own past. But how does this fit in with my work on Auschwitz-Birkenau, death camps and World War I?

These ‘arenas’ of death were constructions (although the carnage of a battlefield was often random, the battles themselves were always planned, ‘constructed’ for the purpose) in stark contrast to the rather arbitrary paths our ancestors took so that we might each be born. Death in these places was designed, it was planned, particularly with regards to the horrors of the death camps and by looking at these places, by visiting them, by looking at the seemingly irrelevant, everyday objects left behind, we can fill in the gaps, each using our own existence to imagine the lives and the deaths of others. We understand what it means to be human, the near impossibility of birth and the absolute certainty of death.

Imagining a group of a several hundred people walking to their deaths, whether down a path to the gas chambers, or on a road to the Front, we can easily imagine the route; we can in places walk the route today. But imagining the paths walked by thousands of people through time, to bring each of the victims into being is almost impossible: I say almost impossible, but, as I’ve written above regarding each of our births, it’s possible in the end.

Looking at death therefore is to to look at life and its inestimable value, whoever we are and wherever we live. It is to understand what it means to be human and to cherish the lives of others.