I’ve been taking a lot of photographs of shadows, particularly that of foliage on pavements. I’m especially keen on the different degrees of ‘focus’ with some parts being sharp whereas others are much more blurred.

Two Worlds

I was thinking about the post World War I landscape and how the years after 1918 saw a surge in spiritualism with grieving parents, wives and children seeking solace in the idea of their loved ones’ continued existence on ‘the other side’. There is, I think, a link with the Pastoral landscapes I’ve been thinking about of late, a place which seems best expressed by the poet Rilke:

And gently she guides him through the vast Keening landscape, shows him temple columns, ruins of castles from which the Keening princes Once wisely governed the land. She shows him the towering trees of tears, the fields of melancholy in bloom (the living know this only in gentle leaf).

In tandem with this boom was the beginning of battlefield tours; tourists would visit the western front when the guns had hardly stopped firing. And I thought how interesting it was that there were these two different ways of looking for those who had gone: one, in a landscape of the imagination, the other, in the physical world; a pastoral plane and a place torn apart by war. And in many respects this reflects my work; the real world which we inhabit today and the plane of the past – a place in which we search for the dead in order that we might empathise with them.

Proposing Moments of Pastoral

Through my research on World War I, I’ve accumulated a large amount of data – postcards, quotes, maps, texts, photographs, personal thoughts and experiences – which I want to start distilling into a new body of work. To do that, I’ve been looking for a ‘lens’ through which I might look again at this archive and thus begin shaping my research into something I can use in a work.

Quotes

A lens could be anything; an image, an experience, a thought, or in this case a quote – or quotes. I’ve discussed them before, but here they are again, the first from Neil Hanson, the second, Paul Fussell:

“As the torrents of machine-gun bullets ripped through the grassy slopes up which the British troops were advancing, the smell of an English summer – fresh cut grass – filled the air. For thousands it would be the last scent they would ever smell.”

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

The smell of an English summer – fresh cut grass – and the idea of moments of pastoral come together to make a lens through which I can re-examine my research. I’ve used Neil Hanson’s quote before, as the title of a piece in 2007 (pictured below), but combined with Paul Fussell’s quote it becomes even more interesting.

The smell of fresh cut grass is a smell I often associate with the past, in particular, my childhood, and as a child, my notion of the past was a pastoral one. To me, the past was an unspoilt place, where squirrels could run the length of the country without touching the ground (a ‘fact’ I always loved). I loved the idea – and I still do – of untouched swathes of forest.

The past was always pastoral.

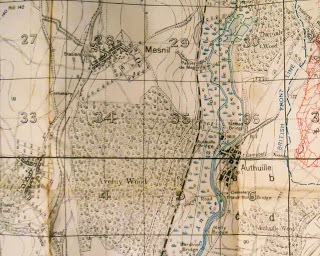

Maps

To pursue my pastoral fantasy, I would create maps of imagined landscapes (something I’ve also discussed numerous times before) and this too has become a lens through which to look at my research. When we think of those who fought in World War I, we often consider only their deaths. We don’t imagine their lives beforehand, especially the fact that not so long before the war, many were still children.

My maps were well-wooded.

As are the trench maps I have in my collection.

Postcards and gardens

There is a link therefore between a pastoral past, my childhood and the consideration of those who died in World War I as children years before – as real people who existed beyond the theatre of war.

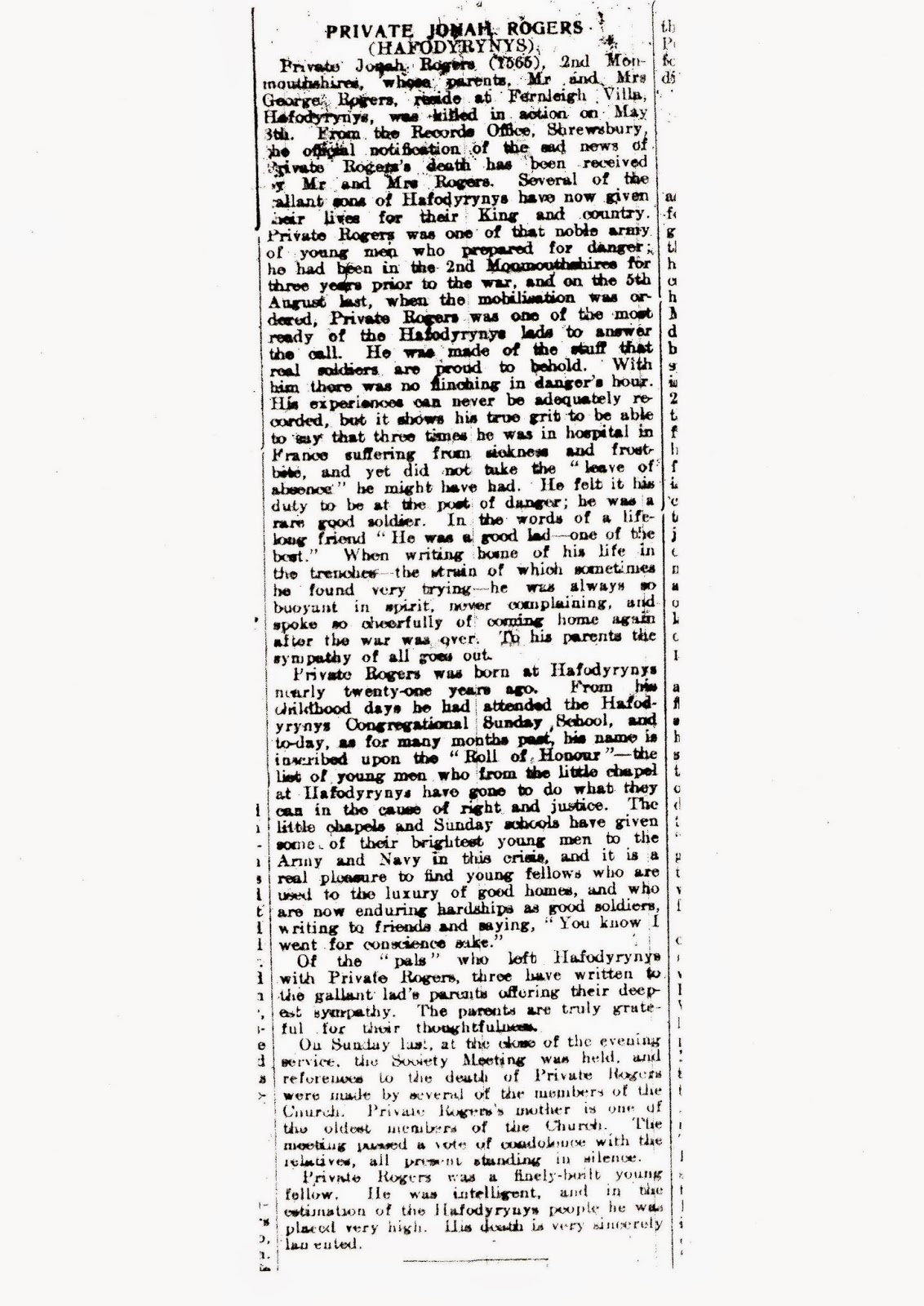

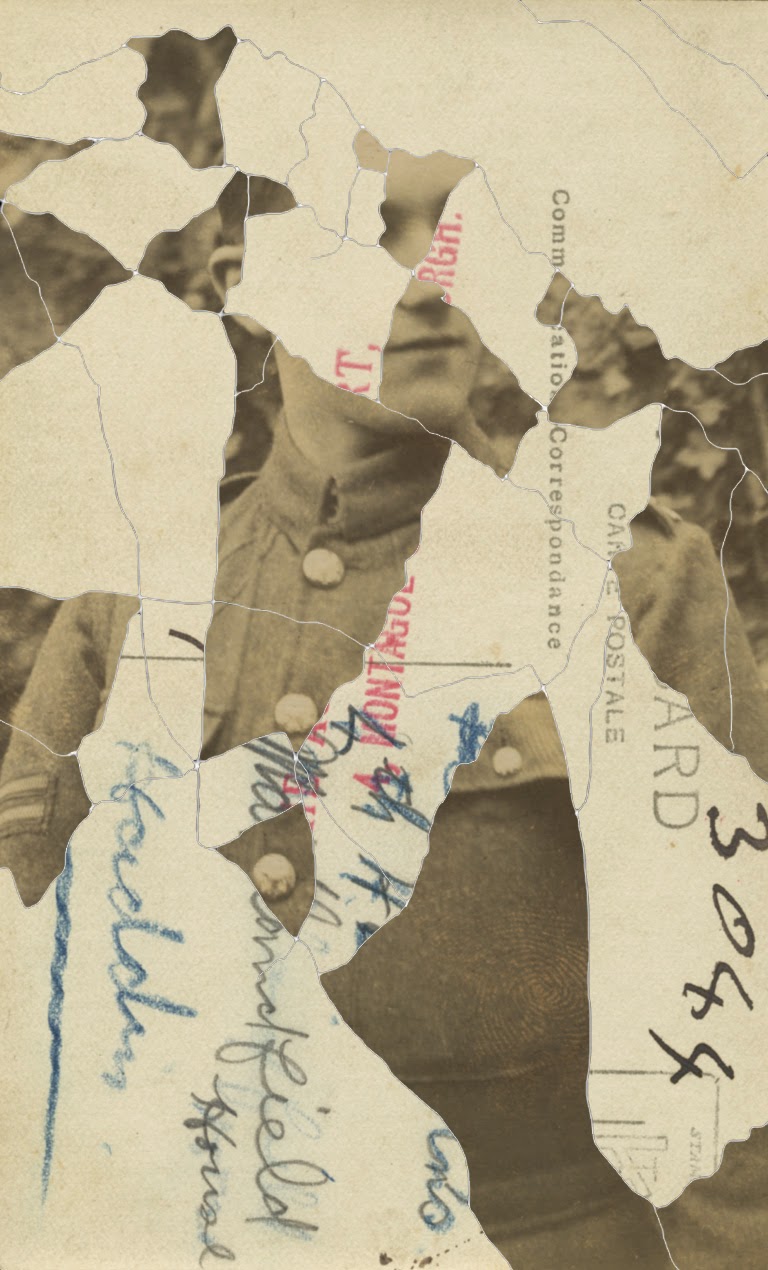

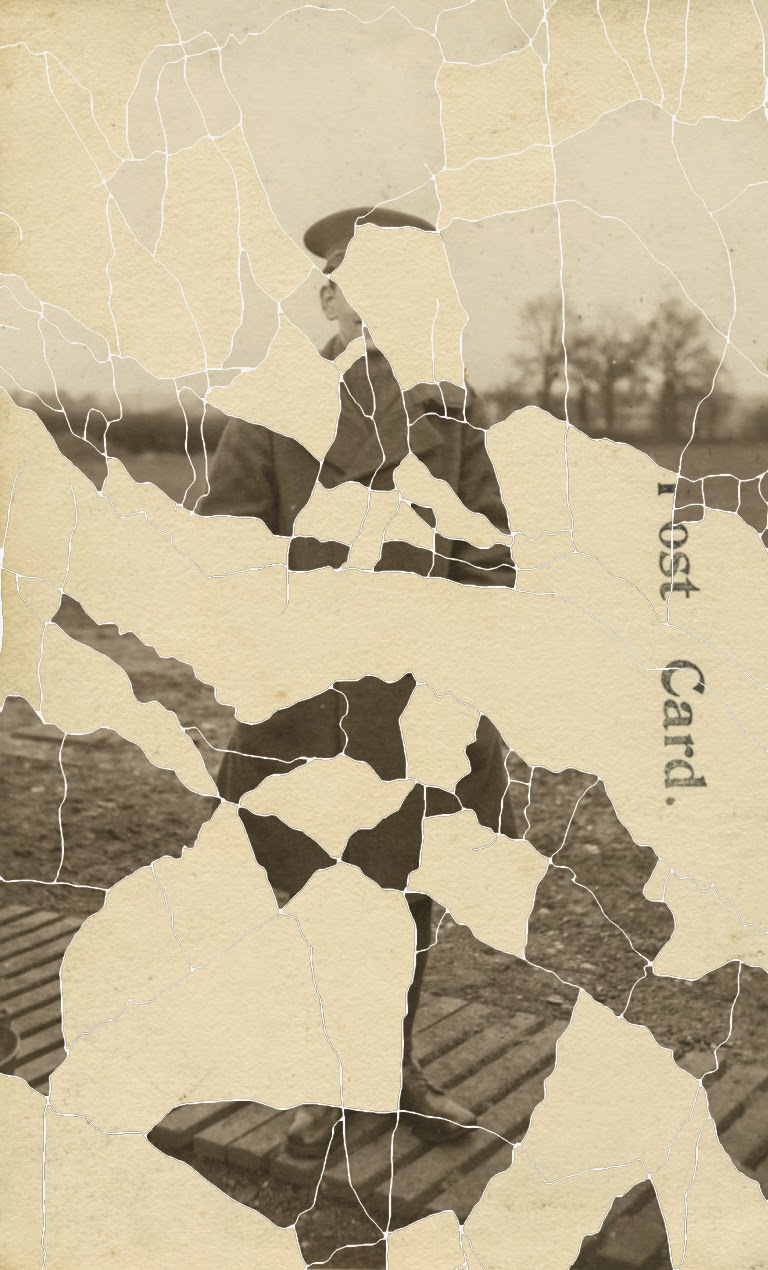

This leads me to postcards, such as the one below:

This postcard shows a soldier posing with his mother(?) standing in what might have been his garden, in the place where, perhaps, he grew up as a child. I might not be able to empathise with him as a soldier directly, but I can well imagine his garden. Part of the landscape of my childhood comprises the gardens of my home and those of my grandparents, as well as parks and playing fields at school. They are pastoral landscapes in miniature, where the grass was cut on a summer’s day.

Proposing moments of pastoral

The question which I haven’t asked is: how do you propose moments of pastoral? The answer to this, I think, is crucial to the development of any work.

To propose is to suggest, invite. It is something given to another.

Maps are objects which propose. But what are they proposing? On the one hand, they propose journeys. More often than not, we use them to plan a journey in the future, for example a day trip or holiday. They require us to use our imaginations; to imagine the future, the landscape and our position within in. They can however propose journeys into the past. In a previous blog about Ivor Gurney, I wrote:

After returning from the war, Ivor Gurney, like so many others suffered a breakdown (he’d suffered his first in 1913) and a passage in Macfarlane’s book, which describes the visits to Gurney – within the Dartford asylum – by Helen Thomas, the widow of Edward Thomas is particularly moving. Helen took with her one of her husband’s Ordnance survey maps of Gloucestershire:

“She recalled afterwards that Gurney, on being shown the map, took it at once from her, and spread it out on his bed, in his hot little white-tiled room in the asylum, with the sunlight falling in patterns upon the floor. Then the two of them kneeled together by the bed and traced out, with their fingers, walks that they and Edward had taken in the past.”

The map they laid on the bed was one that showed the familiar trails and paths of the countryside. But it was also one which, like that I made in my childhood, gave Gurney access to his imagination – to his own past. Together, the patient and his visitor read it with their fingers, following the trails as one follows words on a page. A narrative of sorts was revealed, memories stitched together by the threads of roads, paths and trails.

Maps can also be used of course to orient ourselves in the present. We might consult them to find out where we are or where we ought to go. In fact, they can be used to orient ourselves in the past, present and future.

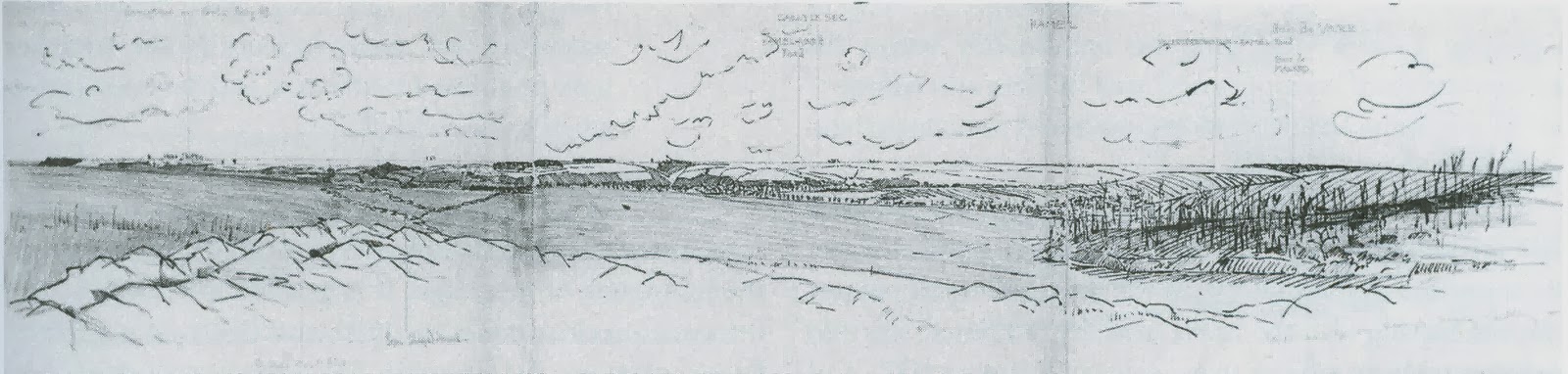

As an artist wishing to propose moments of pastoral, I want to use the form of the map as a starting point. The map might show a pastoral scene, using, for example, the ‘vocabulary’ of the trench map to show the trees.

The Past in Pastoral

July 1st 2016 will mark the 100th anniversary of the infamous Somme offensive. Having already made a lot of work about World War I, I want to mark this anniversary with some new pieces, working around the theme of ‘shared moments of pastoral’.

There have been numerous starting points which, in no particular order, I will outline below.

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.” Paul Fussell

“Here in the back garden of the trenches it is amazingly beautiful – the mud is dried to a pinky colour and upon the parapet, and through sandbags even, the green grass pushes up and waves in the breeze, while clots of bright dandelions, clover, thistles and twenty other plants flourish luxuriantly, brilliant growths of bright green against the pink earth. Nearly all the better trees have come out, and the birds sing all day in spite of shells and shrapnel…” Paul Nash

‘The next day, the regiment began the long march to the Front. In the heat of early summer, nature had made attempts to reclaim the violated ground and a deceptive air of somnolence lay on the landscape. “The fields over which the scythe has not passed for years are a mass of wild flowers. They bathe the trenches in a hot stream of scent,” “smelling to heaven like incense in the sun.” “Brimstone butterflies and chalk-blues flutter above the dugouts and settle on the green ooze of the shell holes.” “Then a bare field strewn with barbed wire, rusted to a sort of Titian red – out of which a hare came just now and sat up with fear in his eyes and the sun shining red through his ears. Then the trench… piled earth with groundsel and great flaming dandelions and chickweed and pimpernels running riot over it. Decayed sandbags, new sandbags, boards, dropped ammunition, empty tins, corrugated iron, a smell of boots and stagnant water and burnt powder and oil and men, the occasional bang of a rifle and the click of a bolt, the occasional crack of a bullet coming over, or the wailing diminuendo of a ricochet. And over everything, the larks… and on the other side, nothing but a mud wall, with a few dandelions against the sky, until you look over the top or through a periscope and then you see the barbed wire and more barbed wire, and then fields with larks in them, and then barbed wire again.”

As the torrents of machine-gun bullets ripped through the grassy slopes up which the British troops were advancing, the smell of an English summer – fresh cut grass – filled the air. For thousands it would be the last scent they would ever smell.’ Neil Hanson

“There was utter silence, broken only by the twitterings of the swallows darting back and forth.” Filip Muller on the murder of a friend in Auschwitz

Centenary

100 years ago, on 8th May 1915, my great-great-uncle was killed in the Second Battle of Ypres.

I’ve written before about this photograph and in particular its location; the idea of the garden as a shared space of memory and experience. Recently, in our own garden we had to have an apple tree taken down due to the fact it had been hollowed out by heart-rot and was in danger of toppling over. I asked for the trunk of the tree to be save in one piece, and when I saw it on the ground, I was reminded again of the idea of gardens as described above.

The trunk of the tree resembled a torso missing its head and limbs.

There was something interesting in the way the bark had grown over a length of wire which had been wrapped around the trunk years ago. It called to mind the cascading lengths of barbed wire rolled out in front of the trenches. It also seemed to turn the trunk into a corpse.

At the same time the tree Is symbolic of a lost idyll; that of the garden of childhood memories.

P is for Pastoral

In her book H is for Hawk, Helen Macdonald writes [my paragraphing]:

“Long walks in the English countryside, often at night, were astonishingly popular in the 1930s. Rambling clubs published calendars of full moons, train companies laid on mystery trains to rural destinations, and when in 1932 the Southern Railway offered an excursion to a moonlit walk along the South Downs, expecting to sell forty or so tickets, one and a half thousand people turned up.

The people setting out on these walks weren’t seeking to conquer peaks or test themselves against maps and miles. They were looking for a mystical communion with the land; they walked backwards in time to an imagined past suffused with magical, native glamour: to Merrie England, or to prehistoric England, pre-industrial visions that offered solace and safety to sorely troubled minds. For though railways and roads and a burgeoning market in countryside books had contributed to this movement, at heart it had grown out of the trauma of the Great War, and was flourishing in fear of the next.

The critic Jed Esty has described this pastoral craze as one element in a wider movement of national cultural salvage in these years…”

This quote interested me in that it tied in with another by Paul Fussell who wrote:

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

Putting these together, I’m reminded as I’ve often written about before of my childhood, when I would create maps of imagined countries (which were in effect imagined pasts) in which I would mentally walk whilst out walking.

Children’s Names

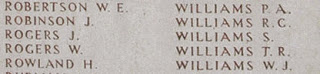

Today is Armistice Day. A day on which the lists of names arrayed in marble and stone, on plaques and in books are at the forefront of many people’s thoughts. Names left behind, as Rilke so beautifully puts it, ‘as a child leaves off playing with a broken toy’.

It was whilst standing with my children on Remembrance Sunday, holding my son as we watched the laying of the wreathes on the town’s memorial that I thought of those names and how, once, they had indeed belonged to children.

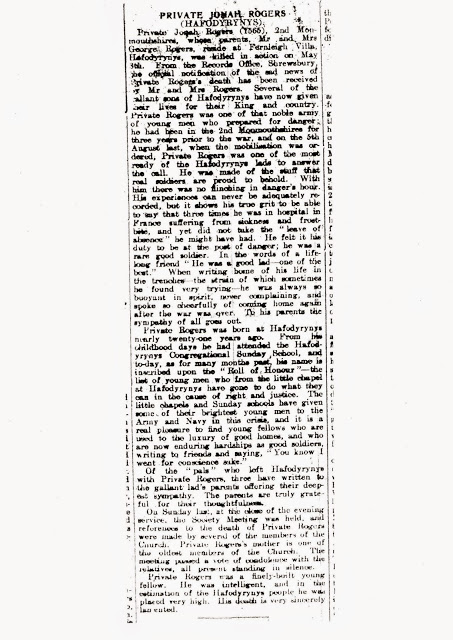

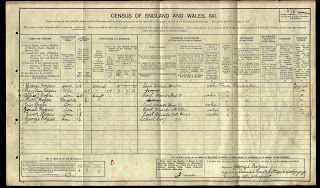

Jonah Rogers was just 22 years old when he was killed near Ypres in 1915. At the end of his obituary there is a moving passage which reads:

“On Sunday last, at the close of the evening service, the Society Meeting was held, and references to the death of Private Rogers were made by several members of the Church. Private Rogers’s mother is one of the oldest members of the Church. The meeting passed a vote of condolence with the relatives, all present standing in silence.”

There is something about that silence which, almost 100 years on, speaks to me about Jonah. It’s as if one can hear the thoughts of his parents and siblings, remembering their son and brother in years passed; not the man dressed in his uniform, sitting on a chair as he poses in a garden for a photograph, but the boy who played in the garden of Tunnel Bank Cottage, Hafodyrynys.

So whilst we remember the names on lists, like Jonah’s on the Menin Gate above, I want to think of two lists that are altogether different, not least because they contain the names of children – of Jonah aged 7 in 1901 and 17 in 1911.

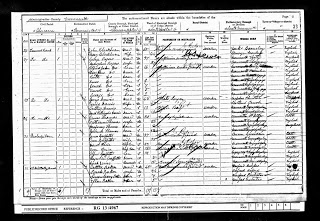

The census from 1901.

The census from 1911.

Silence

In a previous blog, looking at a photograph of Jonah Rogers, I mentioned Roland Barthes’ concept of Punctum; “…that accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me)…” In that photograph (reproduced below) I found it (that poignancy) in the left foot and the missing brick of the flower bed.

In my last blog, in the newspaper clipping reporting Jonah’s death, there is also an especially poignant moment – the clipping’s punctum as it were. And it’s this:

“On Sunday last, at the close of the evening service, the Society Meeting was held, and references to the death of Private Rogers were made by several members of the Church. Private Rogers’s mother is one of the oldest members of the Church. The meeting passed a vote of condolence with the relatives, all present standing in silence.”

It’s there in the last line: The meeting passed a vote of condolence with the relatives, all present standing in silence.

The past is silent (as the tomb which it becomes) and that silence of the relatives, beating inside the church, is one hewn from that immense quietude; a grave cut into another grave. And yet it’s all the louder for it. Imagining the scene, one can hear the silence, punctuated by coughs, scrapes and fidgeting bodies (it’s amazing to think that my grandmother, then three years old, might have been there). There is something too in the silence which serves to throw into relief the image of my ancestors. The writing sets them apart from the rest of those gathered inside. They are silent and just as one imagines those everyday sounds from which silence is made, one can imagine those relatives, standing and recalling everyday things about Jonah… And it’s there that we can get a better picture of Jonah than we can from any photograph.

It’s almost as if the words in that penultimate paragraph, describe something entirely different. One can almost imagine the vote of condolence, the kind words spoken, coming only as murmurs to the relatives; all made shapeless by their mournful introspection.

Jonah Rogers – Newspaper Cutting

I am grateful to Keith Morgan for the following newspaper cutting recording the death of my great-great-uncle, Private Jonah Rogers in 1915. I have transcribed the story below.

Private Jonah Rogers (1565), 2nd Monmouthshires, whose parents, Mr. and Mrs. George Rogers reside at Fernleigh Vila, Hafodyrynys, was killed in action on May 8th. From the Records Office, Shrewsbury, the official notification of the sad news of Private Rogers’s death has been received by Mr. and Mrs. Rogers. Several of the gallant sons of Hafodyrynys have now given their lives for their King and country. Private Rogers was one of that noble army of young men who prepared for danger; he had been in the 2nd Monmouthshires for three years prior to the war and on the 5th August last, when the mobilisation was ordered, Private Rogers was one of the most ready of the Hafodyrynys lads to answer the call. He was made of the stuff that real soldiers are proud to behold. With him there was no flinching in danger’s hour. His experiences can never be adequately recorded, but it shows his true grit to be able to say that three times he was in hospital in France suffering from sickness and frostbite, and yet did not take the “leave of absence” he might have had. He felt it his duty to be at the post of danger; he was a rare good solider. In the words of a lifelong friend “He was a good lad – one of the best.” When writing home of his life in the trenches – the strain of which sometimes he found very trying – he was always so buoyant in spirit, never complaining, and spoke so cheerfully of coming home again after the war was over. To his parents the sympathy of all goes out.

Private Rogers was born at Hafodyrynys nearly twenty-one years ago. From his childhood days he had attended the Hafodyrynys Congregational Sunday school, and to-day, as for many months past, his name is inscribed upon the “Roll of Honour” – the list of young men who from the little chapel at Hafodyrynys have gone to do what they can in the cause of right and justice. The little chapels and Sunday schools have given some of their brightest young men to the Army and Navy in this crisis, and it is a real pleasure to find young fellows who are used to the luxury of good homes, and who are now enduring hardships as good soldiers, writing to friends and saying, “You know I went for conscience sake.”

Of the “pals” who left Hafodyrynys with Private Rogers, three have written to the gallant lad’s parents offering their deepest sympathy. The parents are truly grateful for their thoughtfulness.

On Sunday last, at the close of the evening service, the Society Meeting was held, and references to the death of Private Rogers were made by several members of the Church. Private Rogers’s mother is one of the oldest members of the Church. The meeting passed a vote of condolence with the relatives, all present standing in silence.

Private Rogers was a finely-built young fellow. He was intelligent, and in the estimation of the Hafodyrynys people he was placed very high. His death is very sincerely lamented.

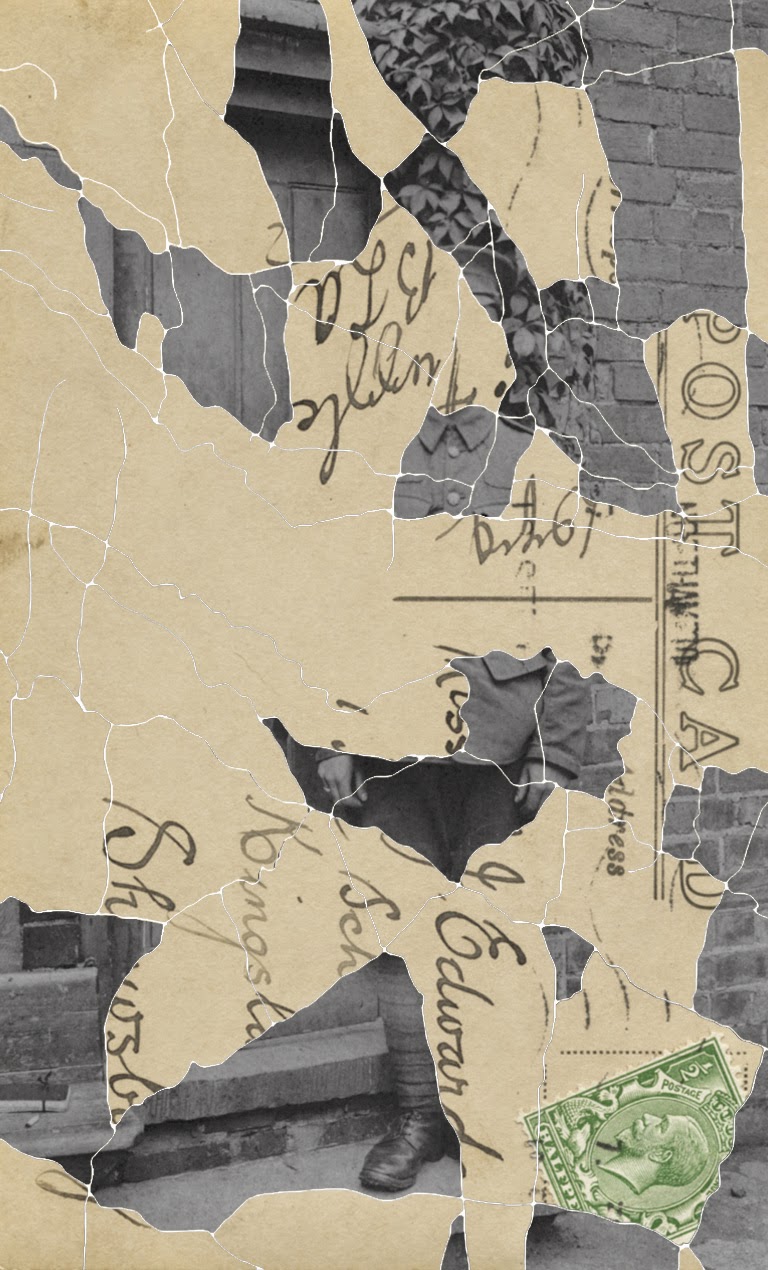

Fragments – New WWI Work

Her Privates We

Whilst reading Frederic Manning’s wonderful novel ‘Her Privates We’, a couple of quotes leapt off the page, particularly as regards my work and the ongoing theme of empathising with past individuals.

“And they were gone again, the unknown shadows, gone almost as quickly and as inconspicuously as bats into the dusk; and they would all go like that ultimately, as they were gathering to go now, migrants with no abiding place, whirled up on the wind of some irresistible impulse. What would be left of them soon would be no more than a little flitting memory in some twilit mind.”

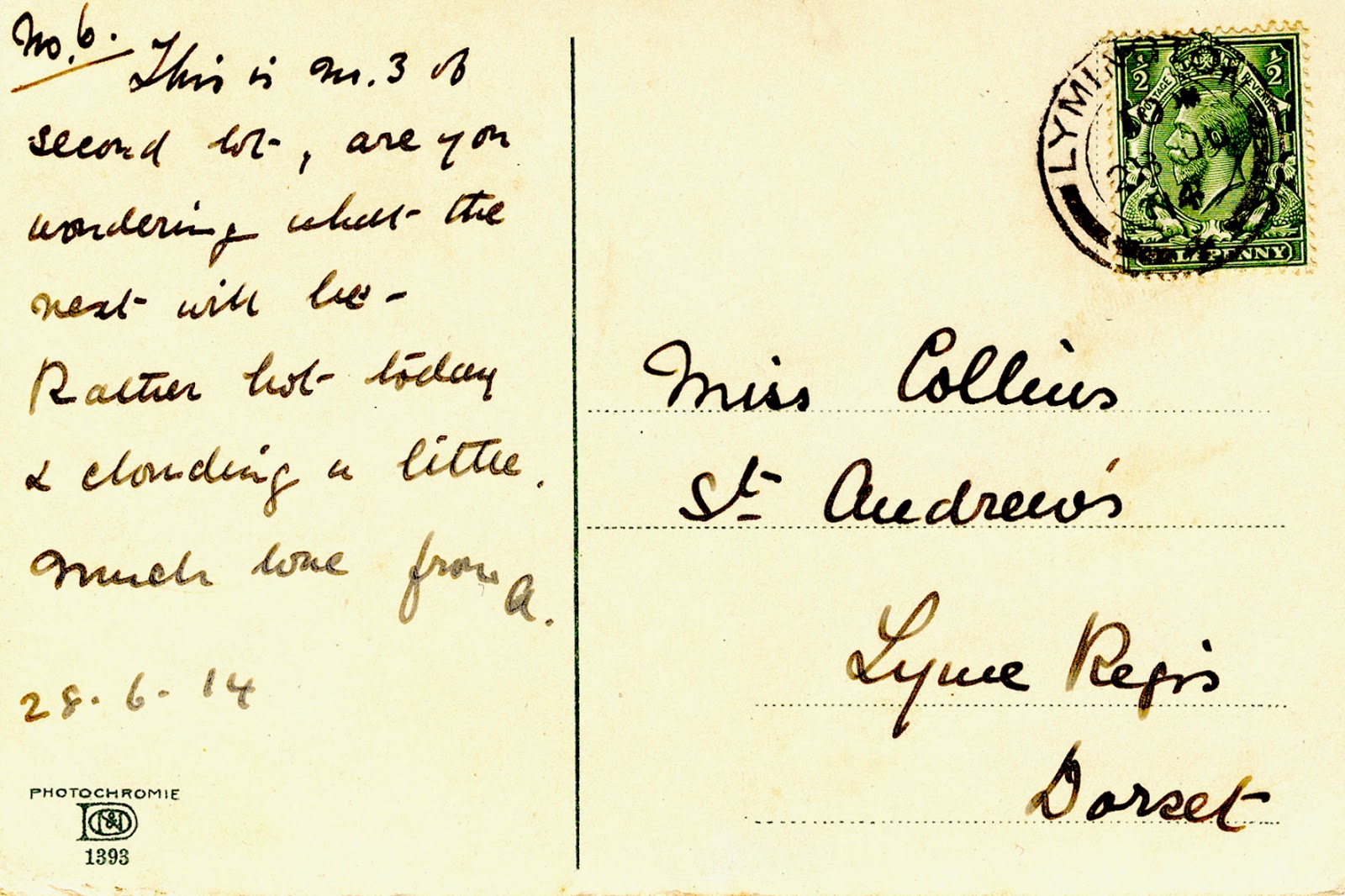

With love from ‘A’ – 100 Years on

With the centenary of the start of World War I (August 4th) almost upon us, today’s date is no less significant. 28th June 1914 was the day on which Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo, thus precipitating a chain of events which was to lead to the chaos and carnage of World War I.

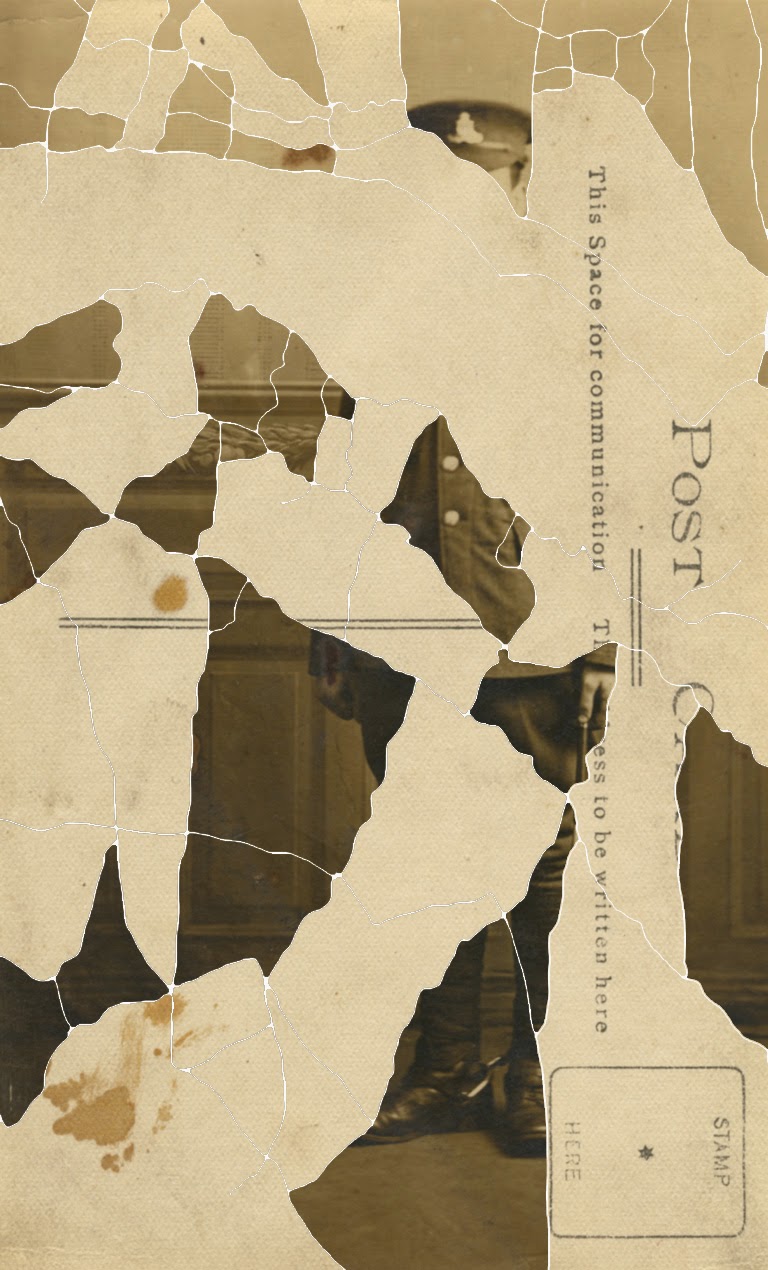

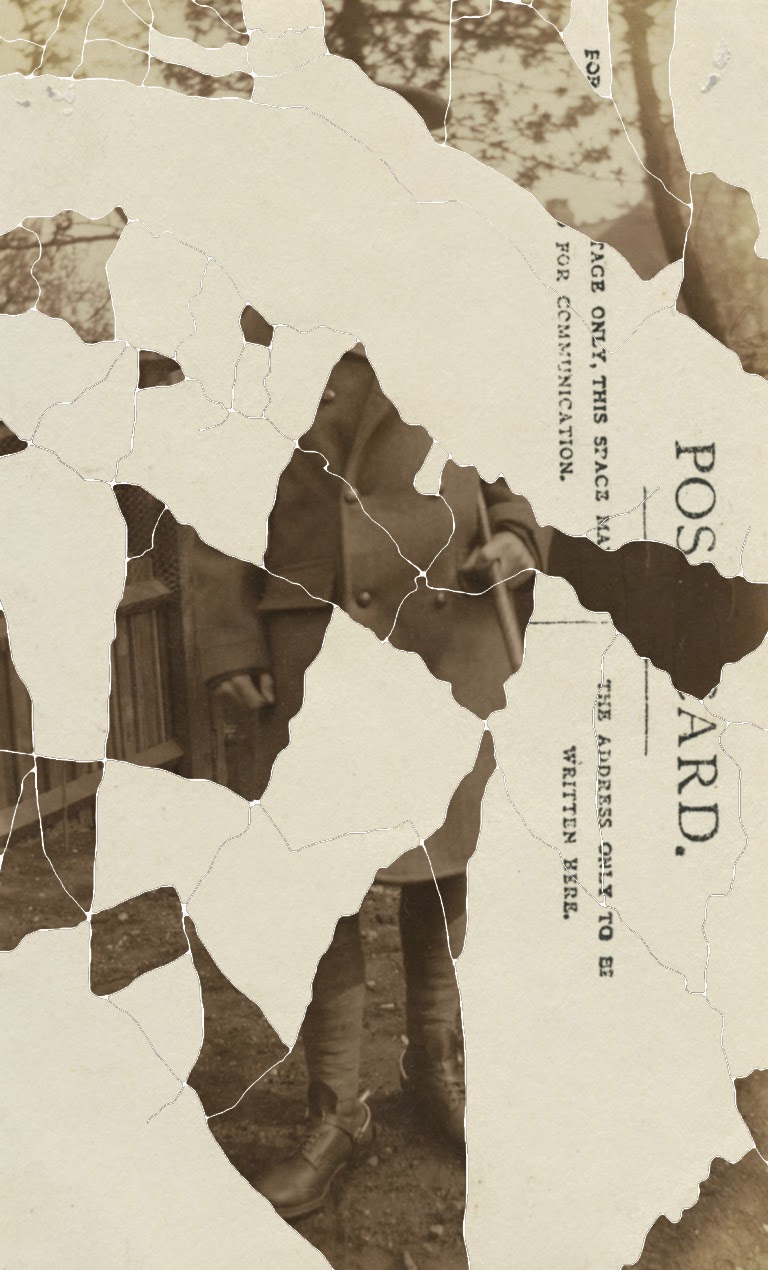

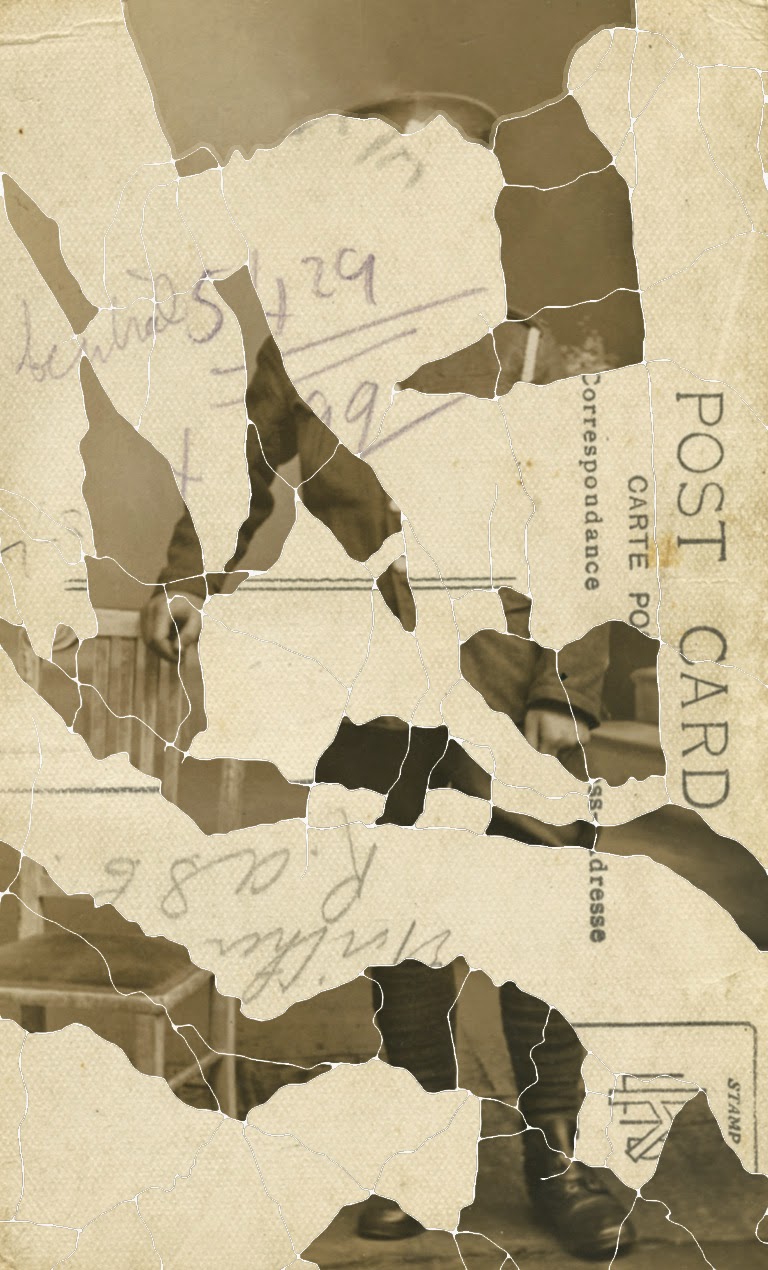

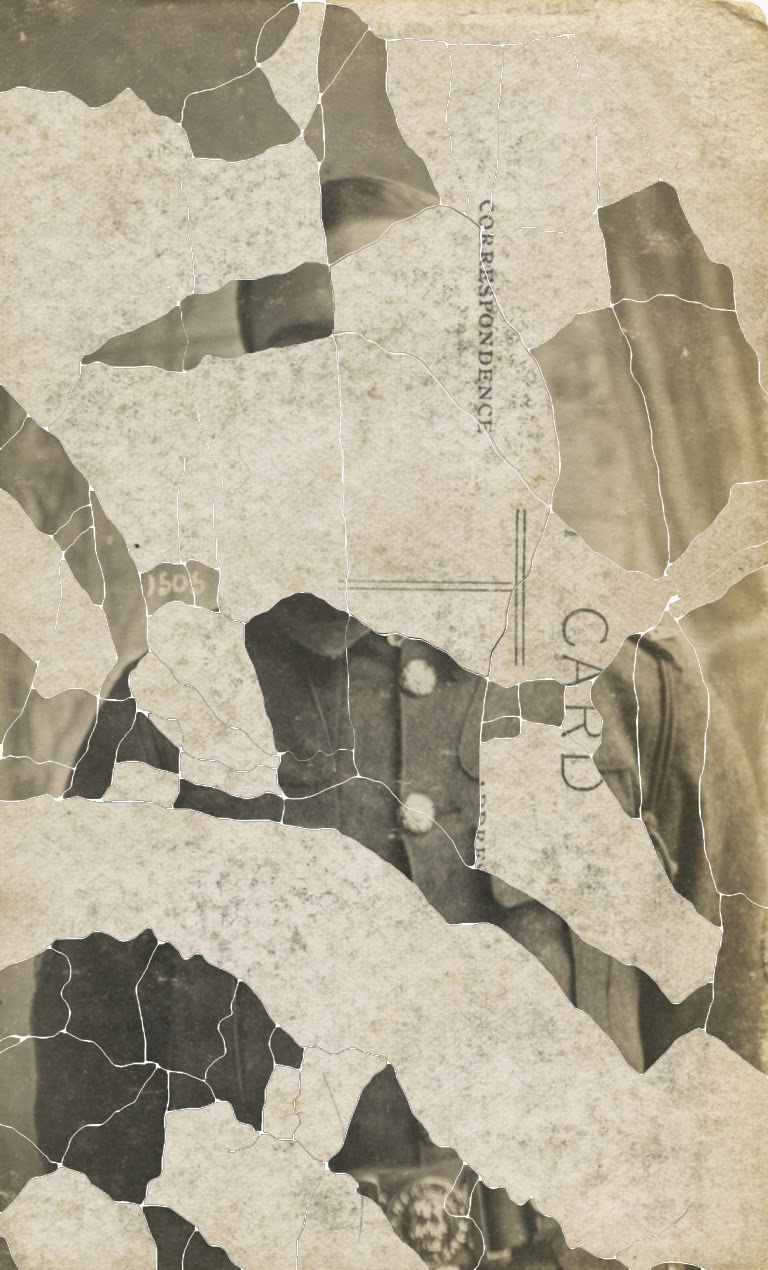

The postcard shown below (both front and reverse) was written on that day, exactly 100 years ago.

Irony

“The irony which memory associates with the events, little as well as great, of the First World War has become as inseparable element of the general vision of war in our time.”

Paul Fussell

The Great War and Modern Memory

Lamenting Trees

‘Ghastly by day, ghostly by night, the rottenest place on the Somme’. Such was how soldiers described High Wood, one of the many that peppered the battlefields of Flanders and France. Woods in name only, these once dense places were quickly reduced to matchwood. One officer, writing of Sanctuary Wood near Ypres, declared that: ‘Dante in his wildest imaginings never conceived the like.’

We, in our wildest imaginations can not conceive the like. So how can we remember and empathise with those who for whom it was real? Historian Paul Fussell provides a starting point:

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

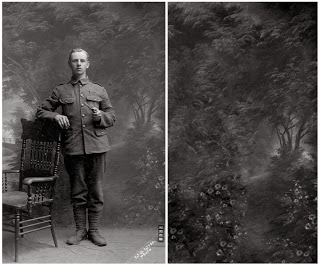

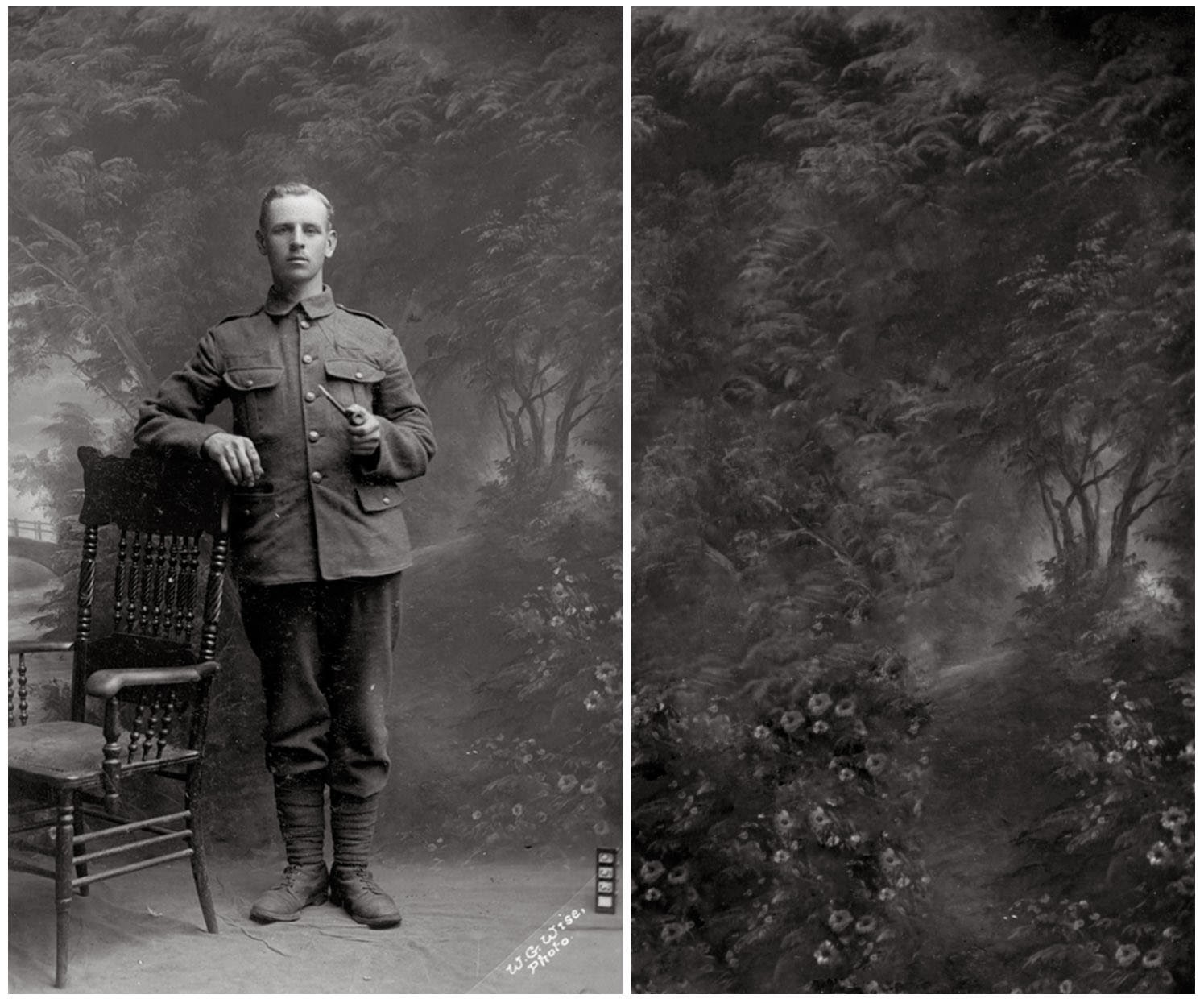

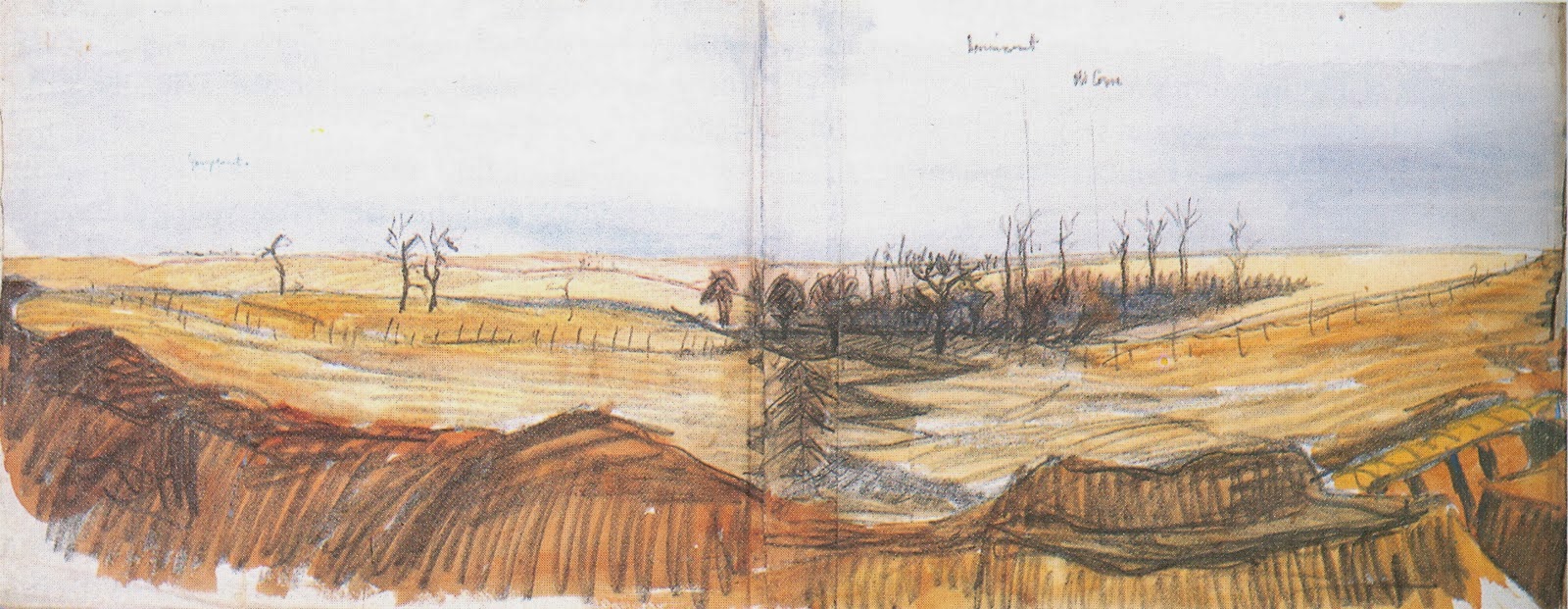

I aim therefore to create a series of pastoral landscapes and accompanying maps which use, as their starting point, portrait postcards of Great War soldiers (in particular, elements found on the studio backdrops against which they were photographed) and Trench maps. Although the pastoral scenes will be empty – devoid of human life – I aim nonetheless to create a sense that people have been there; that the landscape is remembering them – an absence rather than a lack. This will serve to articulate the journeys of those soldiers, from photographic studio to the Front, and for many, death.

Two quotes are useful here; the first from Rainer Maria Rilke’s Duino Elegies:

“Look, trees exist.

The houses we live in continue to stand. Only we

pass away like air traded for air and everything

conspires to maintain silence about us, perhaps

half out of shame, half out of unspeakable hope.”

The other from Wordsworth’s Guide to the District of the Lakes:

“…we can only imagine ‘the primeval woods shedding and renewing their leaves with no human eye to notice or human heart to regret or welcome the change.'”

In Rilke’s poem, the idea of trees (among other things) remembering through their silence those who’ve passed amongst them is particularly appealing and finds a kind of reversed echo in Wordworth’s imaginings of the primeval woods: where it isn’t the human heart regretting or welcoming the change, rather the trees, regretting (or welcoming) our absence.

Words from war poet Edward Thomas serve to further this idea of ‘remembering trees’. In the Rose Acre Papers, a collection of essays published in 1904 he writes:

“…a bleak day in February, when the trees moan as if they cover a tomb, the tomb of the voices, the thrones and dominations, of summer past.”

His widow, Helen, writing after the war in ‘World Without End,’ described how the “snow still lay deep under the forest trees, which tortured by the merciless wind moaned and swayed as if in exhausted agony.’

It’s almost the same lamenting her husband had described before the war.

Richard Hayman, writing in ‘Trees – Woodlands and Western Civilization’ states that “woods are poised between reality and imagination…” As a child woods were, for me, a means of accessing both my imagination and the distant past; a place “for chance encounters” with historical figures, monsters and knights. Woods, as Hayman puts it, are places which can “take protagonists from their everyday lives” while, as I would add, keeping them grounded in the reality of the present.

As a child I would often create maps of imagined landscapes covered – like my imagined mediaeval world – by vast swathes of forest. And as an adult, the act of drawing them returns me to a place where my childhood and the distant past coexist; “a mixture of personal memory and cultivated myth” grounded in the nowness of the present. As such, the ‘pastoral’ landscapes I’m going to paint, based on those strange and incongruous studio backdrops, become too, landscapes of childish sylvan fancies.

When considering the war, much of our attention is, naturally, focused through the lens of its duration: the years 1914-1918. But every one of those men who fought in the trenches was once a child, and since becoming a father this has become an important aspect of my ability to empathise. To empathise, we must see these men unencumbered by the hindsight which history affords us; as men who lived lives before 1914 and beyond the theatre of war. I return to Paul Fussell’s quote (“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral”) and add that we must also see the soldiers who fought not as men, but as children. Again, the words of Edward Thomas serve to articulate this idea; the “summer past” including perhaps those lost years of childhood. Neil Hanson, writing in ‘The Unknown Soldier’ talks of how, on the eve of the Battle of the Somme, the smell in the air was that of an English summer – of fresh cut grass; the smell – one could say – of memories; of childhood.

Returning to Rilke’s Duino Elegies we find another dimension to these landscapes.

And gently she guides him through the vast

Keening landscape, shows him temple columns,

ruins of castles from which the Keening princes

Once wisely governed the land. She shows him

the towering trees of tears, the fields of melancholy

in bloom (the living know this only in gentle leaf).

These pastoral landscapes become therefore, not only the landscapes of childhood imaginings, of “personal memory and cultivated myth”, but the landscape of mourning. The words of Edward and Helen Thomas are especially poignant in this regard; Edward’s trees mourn for a long-lost past; Helen’s for an empty future.

War and The Pastoral Landscape

I’ve been thinking these last few weeks about a new body of work based on the First World War. For a long time – as will be evident from my blog – I’ve been looking at ways of using the backdrops of numerous World War I postcards.

A quote from Paul Fussell has been especially helpful in this regard.

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

The images on the backdrops are these proposed moments.

As a contemporary artist living so long after the war, it is of course impossible for me to create works about the war itself. What I can do however is comment on my relationship to the war (and those affected by it) by creating scenes – pastoral scenes – which use as their starting point the backdrops of World War I postcards.

The pastoral will, therefore, be articulated through the language of war.

These pastoral images will, predominantly, be woodscapes based on places I have visited over the last few years including Hafodyrynys (where my great-great-uncle, Jonah Rogers (1892-1915) grew up), Verdun and the Somme. They might contain – to quote Rilke – ‘…temple columns, ruins of castles’ as per the slightly less pastoral backdrops. They will be devoid of people; the soldiers absent as if they had melted into the backdrops – as if these pastoral scenes represent the Keening landscape of Rilke’s Duino Elegies.

As I’ve written before: it is this absence which the trees express so silently, so eloquently. As Rilke so perfectly puts it:

‘Look, trees exist.

The houses we live in continue to stand. Only we

pass away like air traded for air and everything

conspires to maintain silence about us, perhaps

half out of shame, half out of unspeakable hope.’

The woods I paint will be based, as I’ve said, on those places I have visited as well as those idealised scenes in front of which the soldiers stand in the postcards. They will be – as Richard Hayman puts it – woods “poised between reality and imagination…” – shame and unspeakable hope.

Again as I’ve written before: After the war, the sense of emptiness must have been everywhere. Every insignificant moment – barely acknowledged before the war – now pregnant with a sense of incomprehensible loss. The world, outwardly the same, had shifted just a little, but it had taken the lives of millions to push it there.

There is in this text a sense of absence but also of movement, of continuation – however slight or small (something I want to record in my work). And there’s a link between this and a quote from William Wordsworth who wrote in his Guide to the District of the Lakes: we can only imagine ‘the primeval woods shedding and renewing their leaves with no human eye to notice or human heart to regret or welcome the change.’ I somehow want to turn this quote on its head and borrow from Rilke, who in his Duino Elegies describes the towering trees of tears. I want to paint scenes where there are no people, but in which their absence is recorded, primarily by the trees silently remembering.

“The painter sees the trees, the trees see the painter.”

Absence

In the Tenth Elegy of Rilke’s Duino Elegies we read:

‘…Our ancestors

worked the mines, up there in the mountain range.

Among men, sometimes you still find polished lumps

of original grief or – erupted from an ancient volcano –

a petrified clinker of rage. Yes. That came

from up there. Once we were rich in such things…’

And gently she guides him through the vast

Keening landscape, shows him temple columns,

ruins of castles from which the Keening princes

Once wisely governed the land. She shows him

the towering trees of tears, the fields of melancholy

in bloom (the living know this only in gentle leaf).

And she shows him grazing herds of mourning

and sometimes a startled bird draws far off

and scrawls flatly across their upturned gaze

and flies an image of its solitary cry….

Dizzied still by his early death, the youth’s eyes

can hardly grasp it. But her gaze frightens

an owl from the crown’s brim so it brushes

slow strokes downwards on the cheek – the one

with the fullest curve – and faintly,

in death’s newly sharpened sense of hearing,

as on a double and unfolded page,

it sketches for him the indescribable outline.

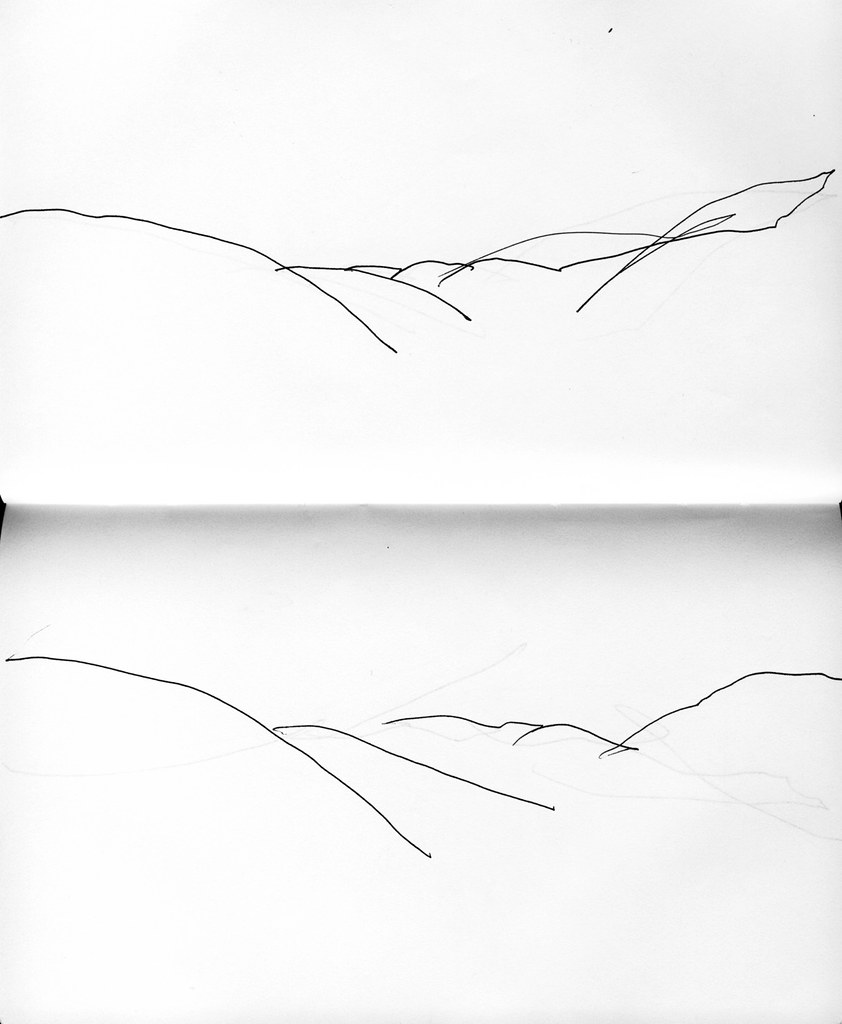

I’ve read this poem numerous times but on a recent reading, the first and last two lines reminded me of some sketches I made during a visit to Hafodyrynys, a town in Wales where my grandmother was born. My great-grandfather, Elias, used to walk from their house, up ‘the mountain’ as my grandmother called it, to Llanhilleth where he worked in the mine. Following in his footsteps, and walking the path he walked almost every day over 100 years ago, I thought of how the shape of the view had barely changed. I sketched it: an indescribable outline on a double and unfolded page.

A young boy in a flat cap pulled over his face

A bell tolls

A girl on her computer sits at the window looking out

Blue, yellow and white balloons

Two distant blasts of a train horn made bigger by the stillness of the air

The cackle of a bird

With regards gesture: Rilke said that the “depth of time” was revealed more in human gestures than in archaeological remains or fossilised organisms. The gesture is a “fossil of movement”; it is, at the same time, the very mark of the fleeting present and of desire in which our future is formed.

The concept of a ‘depth of time’ leads me to consider the phrase ‘a distant past’. How can the past be distant (or otherwise) if the past no longer exists? How can we measure that which we cannot empirically observe? My getting up this morning is as much a part of the past as, for example, the death of Richard III, yet of course there is a difference; a scale of pastness. But how can we measure pastness? We can of course use degrees of time, seconds through to years and millennia, but somehow it seems inadequate. For me, pastness can also be expressed through absence (in particular that of people) and it is this absence which the trees express so silently, so eloquently. “William Wordsworth, writing in his Guide to the District of the Lakes, wrote that we can only imagine ‘the primeval woods shedding and renewing their leaves with no human eye to notice or human heart to regret or welcome the change.'”

‘Look,’ says Rilke, ‘trees exist.

The houses we live in continue to stand. Only we

pass away like air traded for air and everything

conspires to maintain silence about us, perhaps

half out of shame, half out of unspeakable hope.’

When speaking of distance in relation to the past (the distant past), I think of distance as it’s perceived in the landscape; a measurement defining the space between me and something else. Putting the two together, the ‘distant past’ becomes something internal, carried in relation to the external world; the sum of those absences I carry through the landscape.

Rilke’s description of the Keening landscape reminded me too of the landscapes which I created as a child (see also Maps). These were ‘places’ based on how I perceived the landscape of the past; in particular, its swathes of ancient and unspoiled forests. As Richard Hayman puts it: “woods are poised between reality and imagination…” Whenever I was in a wood – however small – I always experienced it with my imagination.

Which brings me round to recent work I’ve been doing on World War I backdrops.

Seeing the young soldier standing before a bucolic backdrop, one is reminded of the youth in Rilke’s poem being led through the Keening landscape.

For some time, I’ve been wanting to create landscapes based on these postcards, landscapes about the Great War which do not seek to illustrate its horrors but articulate our present day relationship to it. A quote by Paul Fussell is important in this respect:

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

The landscape behind the soldier becomes the Keening landscape described by Rilke, a moment of pastoral as described by Fussell. In the right hand image, the soldier has gone; the landscape is one filled with ‘the towering trees of tears, the fields of melancholy.’ It is an image of the past: as Ruskin wrote: a tree “is always telling us about the past, never about the future.” It is an image of absence, a kind of which only the trees can speak.

Chaos Decoratif

Paul Fussell Quote

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

Taken from ‘A Terrible Beauty’ by Paul Gough

Paul Nash Quote

“Here in the back garden of the trenches it is amazingly beautiful – the mud is dried to a pinky colour and upon the parapet, and through sandbags even, the green grass pushes up and waves in the breeze, while clots of bright dandelions, clover, thistles and twenty other plants flourish luxuriantly, brilliant growths of bright green against the pink earth. Nearly all the better trees have come out, and the birds sing all day in spite of shells and shrapnel…”

Paul Maze (1887-1979)

- 1

- 2

- 3

- …

- 5

- Next Page »