I’ve been taking a lot of photographs of shadows, particularly that of foliage on pavements. I’m especially keen on the different degrees of ‘focus’ with some parts being sharp whereas others are much more blurred.

Centenary

100 years ago, on 8th May 1915, my great-great-uncle was killed in the Second Battle of Ypres.

I’ve written before about this photograph and in particular its location; the idea of the garden as a shared space of memory and experience. Recently, in our own garden we had to have an apple tree taken down due to the fact it had been hollowed out by heart-rot and was in danger of toppling over. I asked for the trunk of the tree to be save in one piece, and when I saw it on the ground, I was reminded again of the idea of gardens as described above.

The trunk of the tree resembled a torso missing its head and limbs.

There was something interesting in the way the bark had grown over a length of wire which had been wrapped around the trunk years ago. It called to mind the cascading lengths of barbed wire rolled out in front of the trenches. It also seemed to turn the trunk into a corpse.

At the same time the tree Is symbolic of a lost idyll; that of the garden of childhood memories.

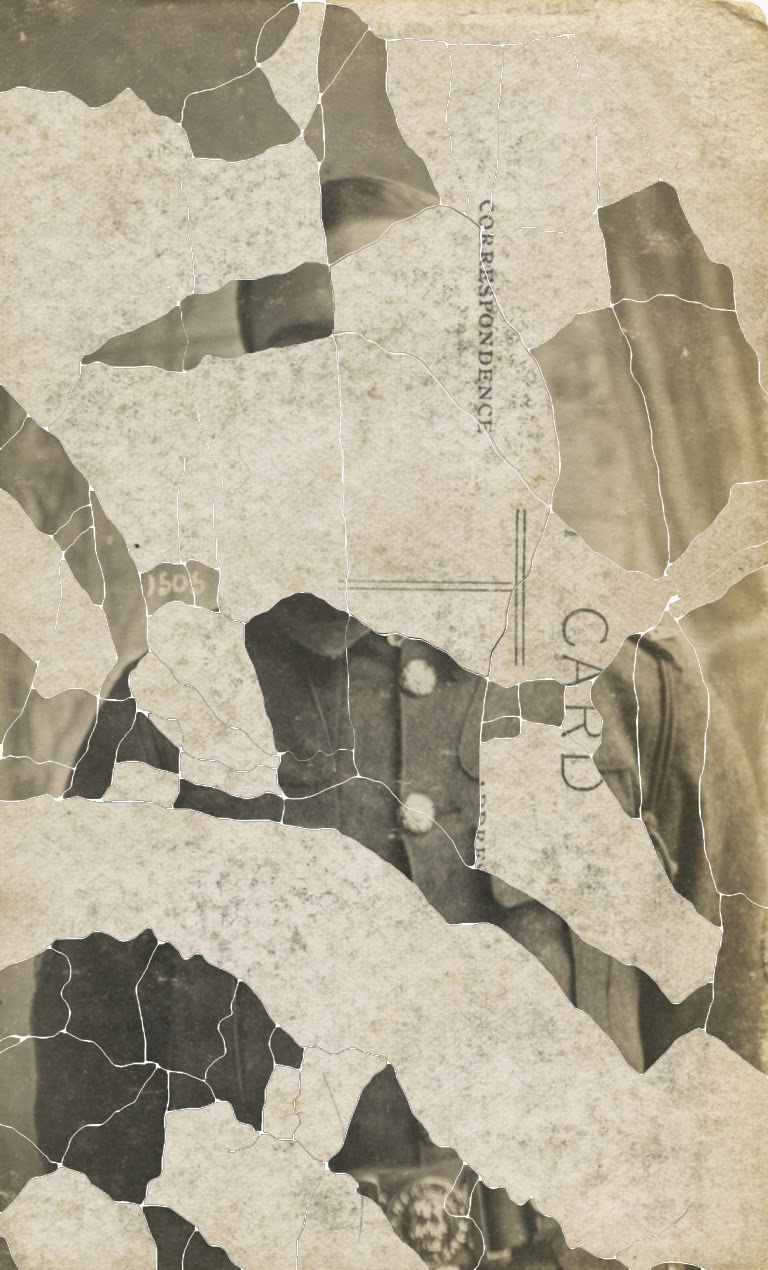

Fragments – New WWI Work

Jonah Rogers – New Photograph

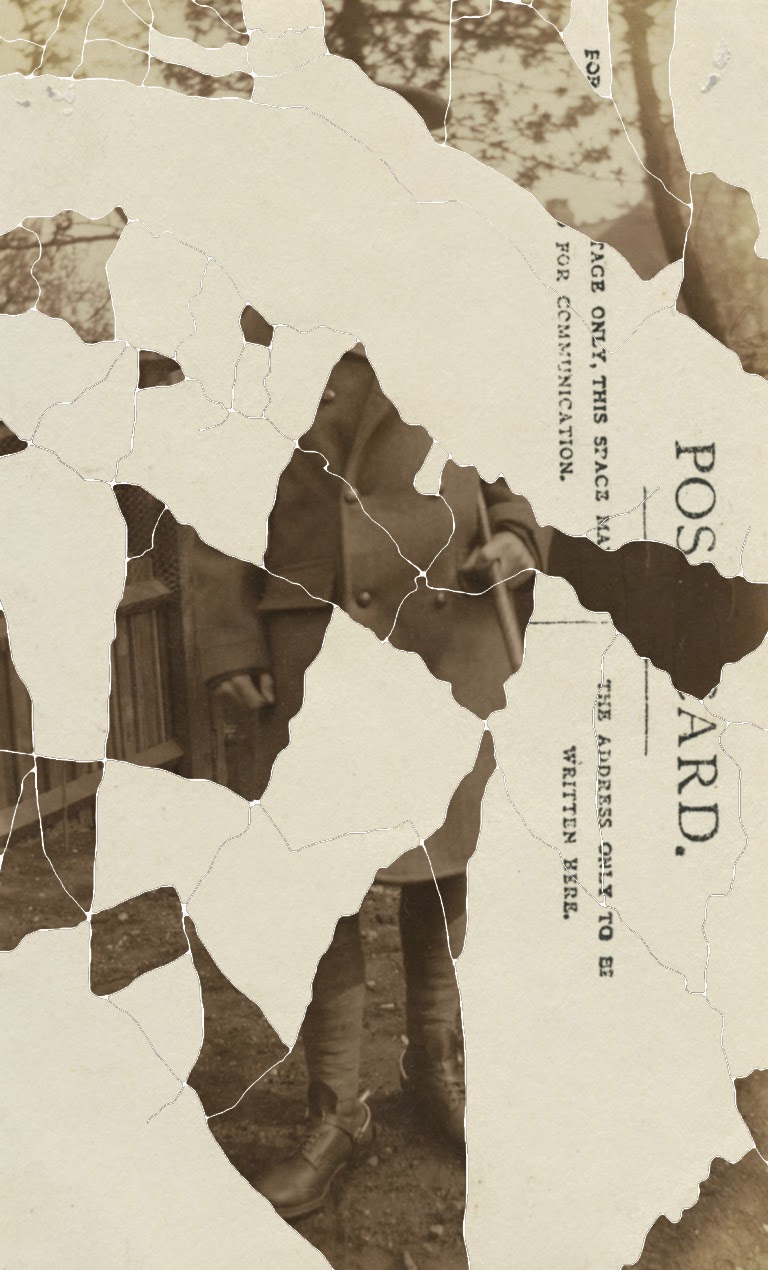

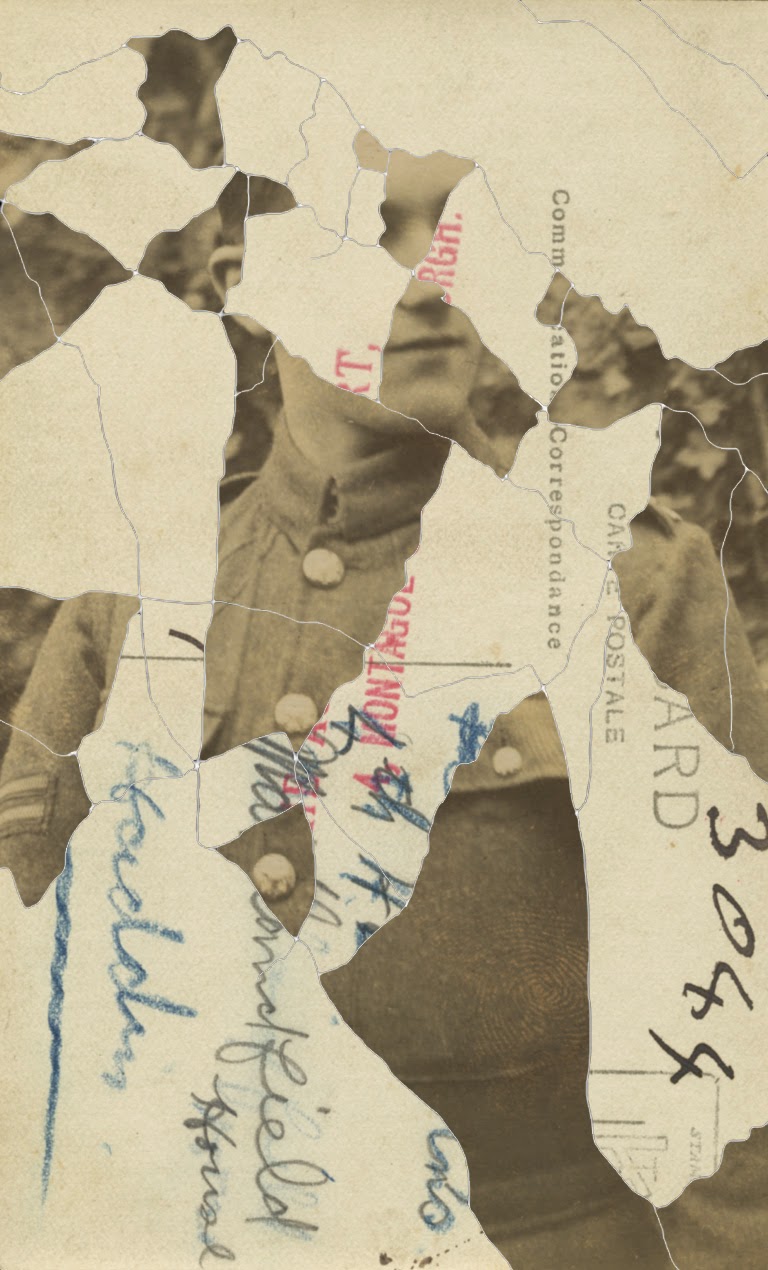

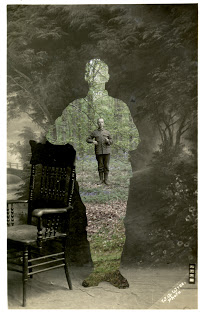

It’s been six years since I discovered my great-great-uncle, Jonah Rogers, killed in action on May 8th 1915. In that time I have also been collecting World War I postcards, portraits of soldiers taken before they left for the Front. Now, thanks to a descendent of Jonah’s sister Ruth (my grandmother was the daughter of another sister, Mary Jane) I have, in this centenary year, been sent a postcard of Jonah Rogers. The quality of the reproduction isn’t high but I’m hoping to see the original soon.

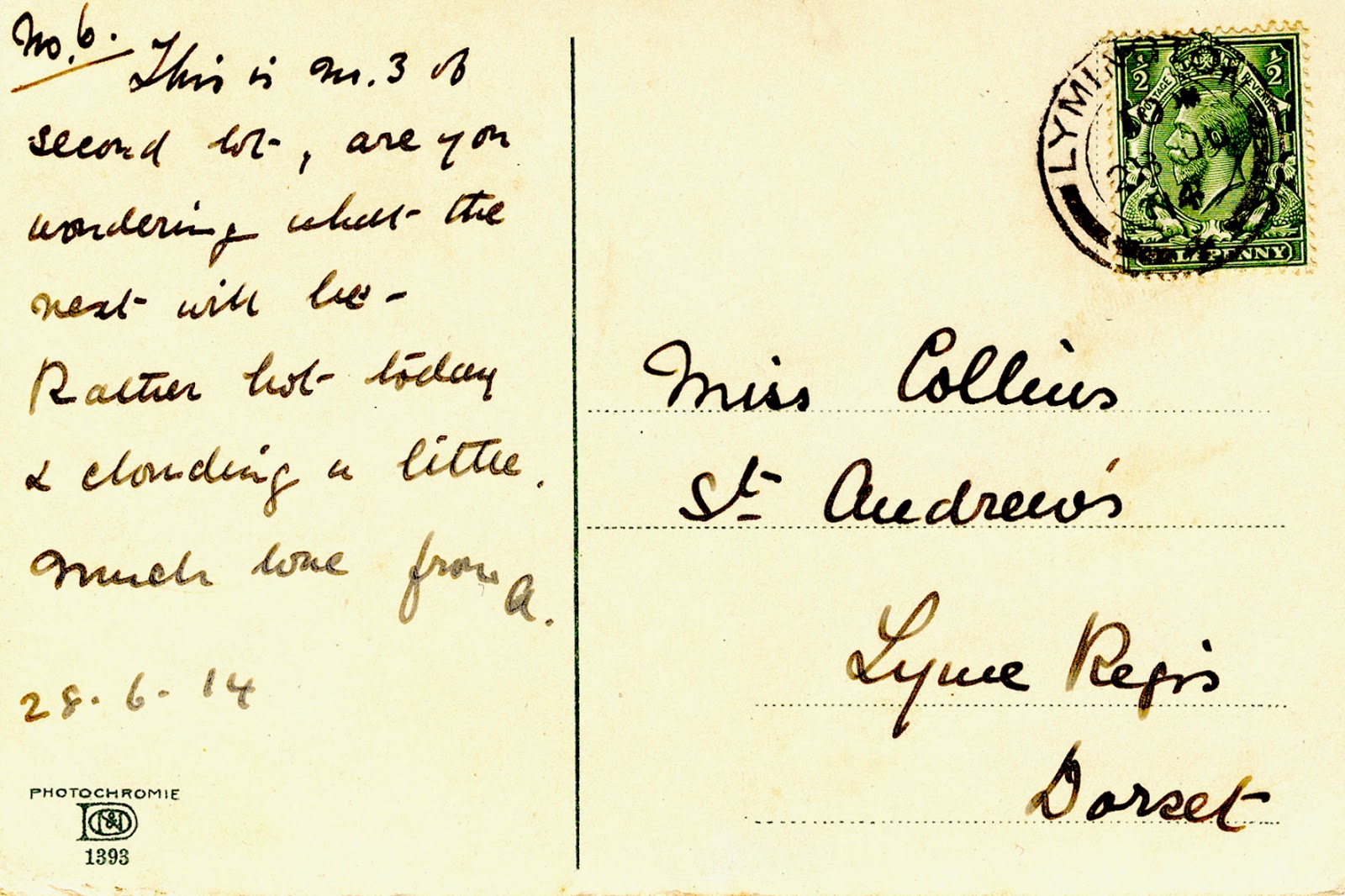

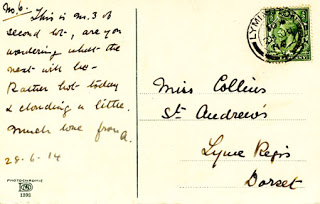

With love from ‘A’ – 100 Years on

With the centenary of the start of World War I (August 4th) almost upon us, today’s date is no less significant. 28th June 1914 was the day on which Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo, thus precipitating a chain of events which was to lead to the chaos and carnage of World War I.

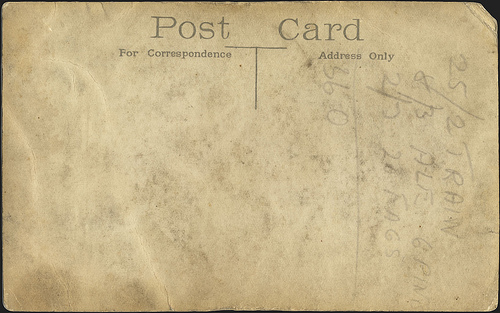

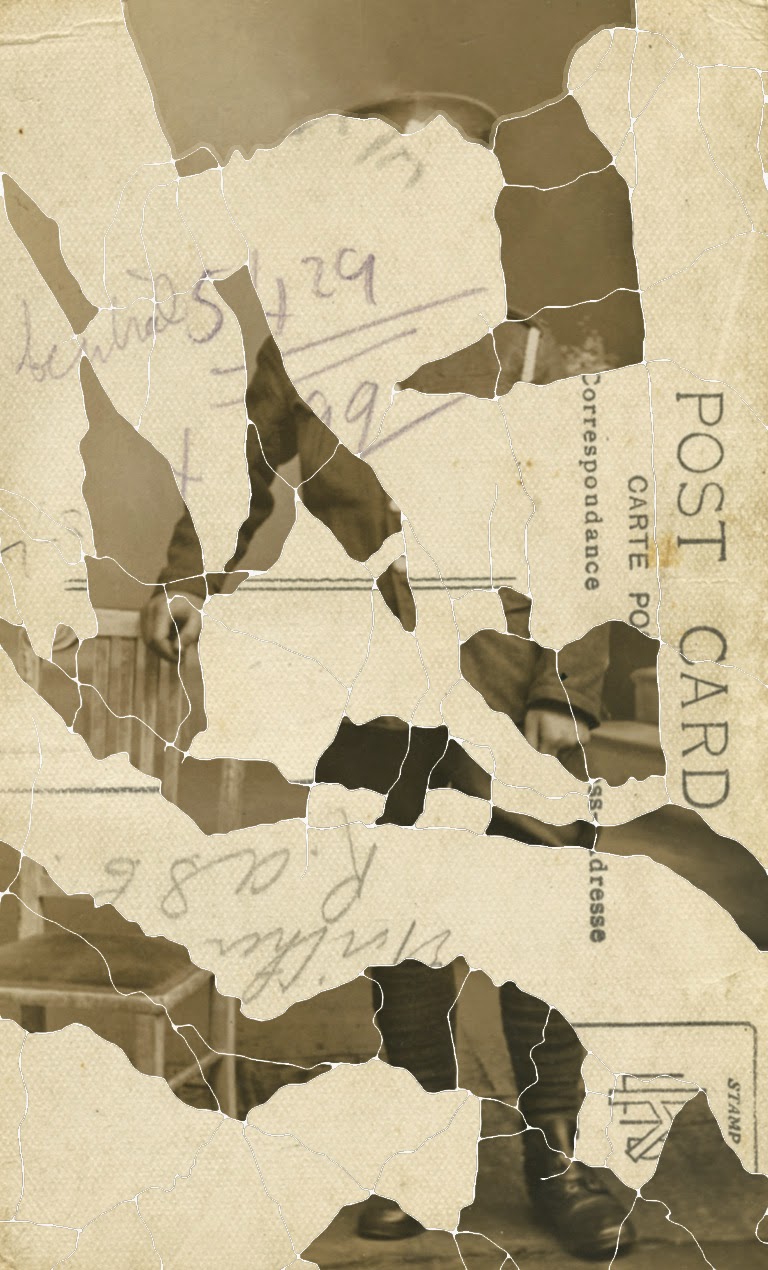

The postcard shown below (both front and reverse) was written on that day, exactly 100 years ago.

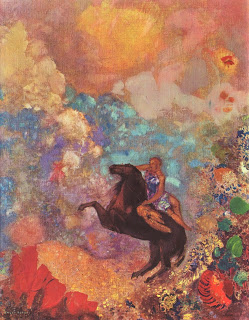

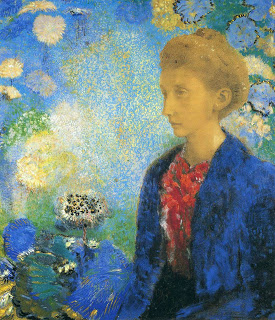

Backdrops (Odilon Redon)

A Backdrop to Eternity

Below is a typical, early 20th century studio portrait. The subject – a boy – sits on a prop. Behind him hangs a backdrop on which is painted an idealised scene – something like the view of a country estate with trees, balcony and lake.

When I first got the photo (as part of a job-lot of old photographs) I gave it a cursory look and that was that. I hardly noticed the backdrop behind, which is perhaps the point.

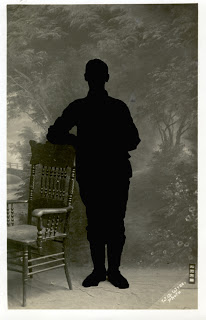

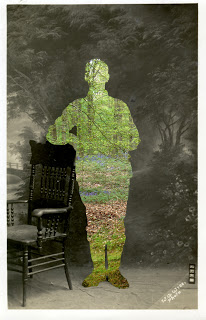

The image below is another studio portrait from around the same time. The subject rests upon a prop – in this case a chair. Behind him hangs a backdrop – a bucolic scene replete with woodland path, flowers, river and bridge – and again, when I first looked at the photograph – given to me as part of a collection of around 200 – I hardly noticed the backdrop; my eyes were drawn only to the soldier. But as I began analysing the backdrops of other postcards in the collection, becoming more aware of the differences between studio-based portraits, and those taken in more informal, often domestic settings, I started to think more about these backdrops.

“We whose generations are ordained in this setting part of time, are providentially taken off from such imaginations. And being necessitated to eye the remaining particle of futurity, are naturally constituted unto thoughts of the next world, and cannot excusably decline the consideration of that duration, which maketh Pyramids pillars of snow, and all that’s past a moment.”

That click of the camera, that moment, would, when pressed against the face of eternity, encompass all that has so far come and gone since the Universe began. It’s a concept quite impossible for the human mind to hold and so – in some – the void is filled with God and an afterlife. After the war, many of the bereaved tried to fill the void left in their lives through Spiritualism, attempting to contact their loved ones in an eternity filled perhaps with pre-war, picture-postcard landscapes; trees, fields, flowers, rivers and so on. And in many ways, the photographs of the soldiers above, become not images of insignificant moments made before their departure, but images of their place in an eternal moment once the war was done.

After the war, the sense of emptiness must have been everywhere. Every insignificant moment – barely acknowledged before the war – now pregnant with a pervasive sense of incomprehensible loss. The world was outwardly the same, shifted just a little, but it had taken the lives of millions to push it there.

New Work 3

New Work 2

New Work

Work in Progress

New Work in Progress (WW1)

Projections

Having completed my last stitching project based on trench maps from World War I, I decided to try and superimpose some postcard portraits onto them, of soldiers headed for the Front. In the first (below) I used the photograph of a family which I ‘projected’ onto the map as shown hanging on a washing line.

What strikes me about this image as a whole, is the contrast between now and then as it exists in the contrast between the black and white of the photograph and the colour of the day. This colour, and the sense of the nowness of the present, helps strengthen my own empathetic feelings towards those long since lost – and all but forgotten – to history.

The fact the map hangs on a line like an item of washing, also reinforces the sense of domesticity which is a theme running through some of the postcard portraits, many of which were taken in the backyards of soldiers (or their parents), where evidence of the everydayness of domestic life is in abundance.

One such photograph shows a young couple who’ve recently been married. They stand, unsure of what the future brings, both wearing a look full of apprehension, staring into the lens of the camera, as if this ‘clock for seeing’ as Barthes once referred to them, really could show them the future.

The image onto which their portrait has been projected shows the reverse side of the map, where the threads used to stitch the past together hang like the cut threads of countless lives.

Serre Palimpsest (completed)

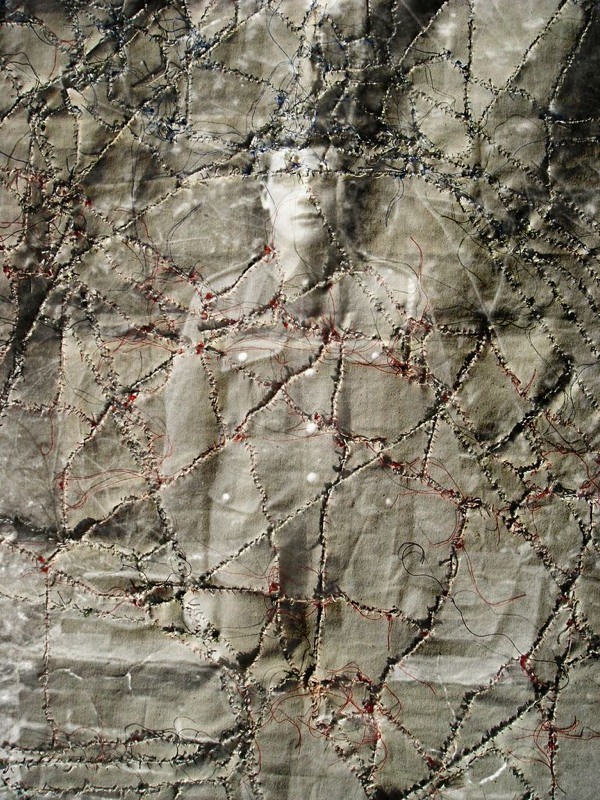

I’ve just completed – after several weeks of stitching – a piece of work called ‘Serre Palimpsest’ the creation of which I’ve been documenting on my blog. It became apparent soon after I started this work that this was a piece with two sides which may seem an obvious thing to say, but it seemed to me that the two sides we’re saying different things, just as things below the surface say something different to those above, whilst as the same time remaining connected.

The two images below show the completed work. The first, the front:

The second, the reverse:

The lines stitched in black show the roads before the war (the modern day road system is pretty much the same), the blue stitching and red show the British and German trenches respectively – with No Man’s Land between, and the green stitching shows the modern day field boundaries.

What was interesting about creating the work was how the threads from the reverse of the piece would emerge into the front, mirroring the way pieces of the past (bits of old shell etc.) find their way to the surface after many years below the ground. The cut lines on the reverse made me think of the paths soldiers would have taken to get there; paths which in many cases were cut in the Somme.

Occasionally, the threads would be tied together on the reverse which again made me think of how our lives today are similar to those who died in that their lives were lived lives too; of course their circumstances couldn’t have been more different, but the fact is that the vast statistics of the Somme comprise real individuals.

To take the photographs I hung the piece on the washing line. The weather was unseasonably hot and sunny, much like the weather would have been on the first day of the Battle of the Somme (1st July 1916). As I looked as the work swaying gently in the breeze, I thought about the photographs taken in the back gardens of those who were about to set off for the Front. I was reminded too of the backdrops used in studio-based photographs.

Two Soldiers

I was once given a collection of 200 World War I postcards featuring portraits of soldiers and have always wanted to trace some of those featured. Through research on the National Archives website and through deciphering rather bad handwriting I discovered that the man immediately below is one Walter Henry Chevalier who served in the Army Service Corps and Northumberland Fusiliers. I think, if my research is correct, that he survived the war, dying in 1962 aged 64.

Below, another World War I soldier and another survivor. The rather splendid surname ‘Dangerfield’ is written on the back and having searched for him and got over 100 Dangerfields I had a closer look at the image. The spurs and the crop suggest of course something to do with horses and the cap badge as far as I can see is that of the Royal Horse Artillery. Having refined my search, I found Edward Paul Dangerfield, Second Lieutenant in the Royal Horse Artillery. Again, if my research is correct, he survived the war and died in 1978.

Empathy and the First World War (Part 2)

In many respects then, this image is, for me, quite an unsettling one – even more than that I discussed before. ‘The men that we’re about to bury,’ the men seem to be saying, ‘are just like you’. (I was reminded, looking at this image, of the fact that when soldiers marched to the front, just before an attack, they sometimes saw the huge pits dug in preparation for their deaths.)

But would such interpretations arise if the image were black and white? My feeling is they wouldn’t and having made the image monochrome, I can see why.

For one thing, it ceases to be an image into which I feel I could step; it remains very much an image. Colour delineates distance, whereas in black and white the image seems a lot flatter. (I have to point out that I’m not suggesting black and white photos don’t convey distance, or that this colour image, made black and white accurately reflects how it would look if shot on black and white film. The autochrome process, when made black and white like this, makes the resulting image very grainy). Secondly, the men no longer seem to be looking at me, but rather at the photographer. But most importantly, as a black and white image, this picture ceases to be about the soil, the substance which, during the war claimed both the living and the dead. The distinction between the soil and the grass is lost – a distinction which, in light of the time (1919), is especially poignant. Nature returns to reclaim what’s hers, and following the gaze of the diggers, that includes us. World War I was about, amongst many other things, the soil and vast ruination – and that is what this image is about. The grass comes as it comes upon castles ruined over long stretches of time. But as Christopher Woodward writes in his book In Ruins ‘Nature’s agent does not have to be flowers or fig-trees. In the case of Van Gogh, it was the miserable mud of Flanders.’

I see this photograph very much in terms of its texture. I see its weight, as if its colour makes it synaesthetic: I see in terms of touch. Empathy – as regards an empathetic understanding of this image – does not mean I empathise with what these men were doing when the photograph was taken, or what they too had certainly endured in the preceding years of war, but that I can see this moment as having once been now. As I wrote before, if anything hinders an empathetic engagement with the war, it’s the sense that it’s always already happened. In this image, it has already happened, but the wounds are still raw.

Empathy is a dialogue between bodily experience and knowledge. Visiting a battlefield, what we know of the war influences our bodily experience and vice-versa. Empathy is in many respects articulated through metaphor. The same is true of the photograph; but whereas on a battlefield we stand in the landscape, we can only look at the image, such is where a synaesthetic response is so important, and synaesthesia is after all a kind of metaphorical discourse.

A Poignant Postcard

As part of my forthcoming exhibition, I’ve been purchasing a few postcards for a piece of work, one which mirrors previous works I’ve made with postcards of World War One soldiers. One of my recent acquisitions can be found below.

The postcard shows a quiet, tranquil beach scene, which when one looks at the reverse becomes particularly poignant.

It was posted in the summer of 1914, just a few weeks before the outbreak of World War One. What’s more, the date at the bottom, 28th June 1914, is the date that Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir apparent to the Austro-Hungarian throne was assassinated in Sarajevo.

Future Work

Mine the Mountain 2

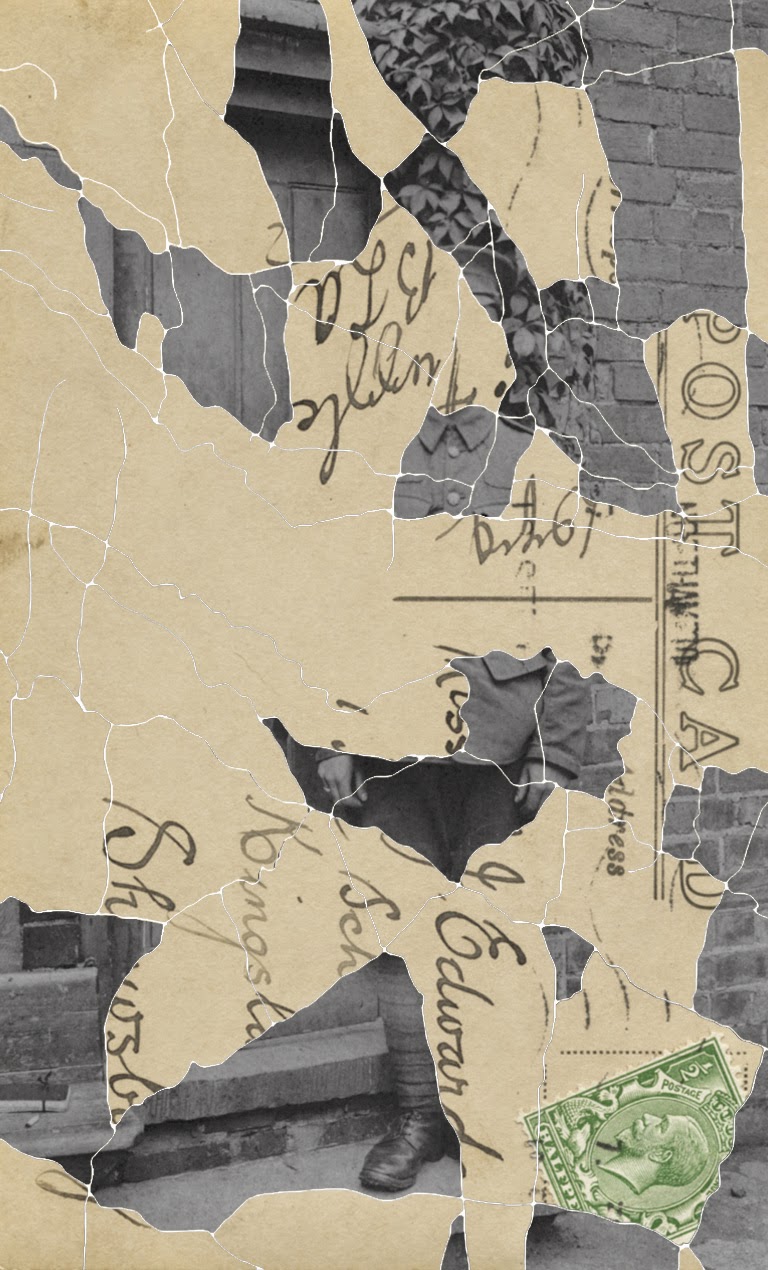

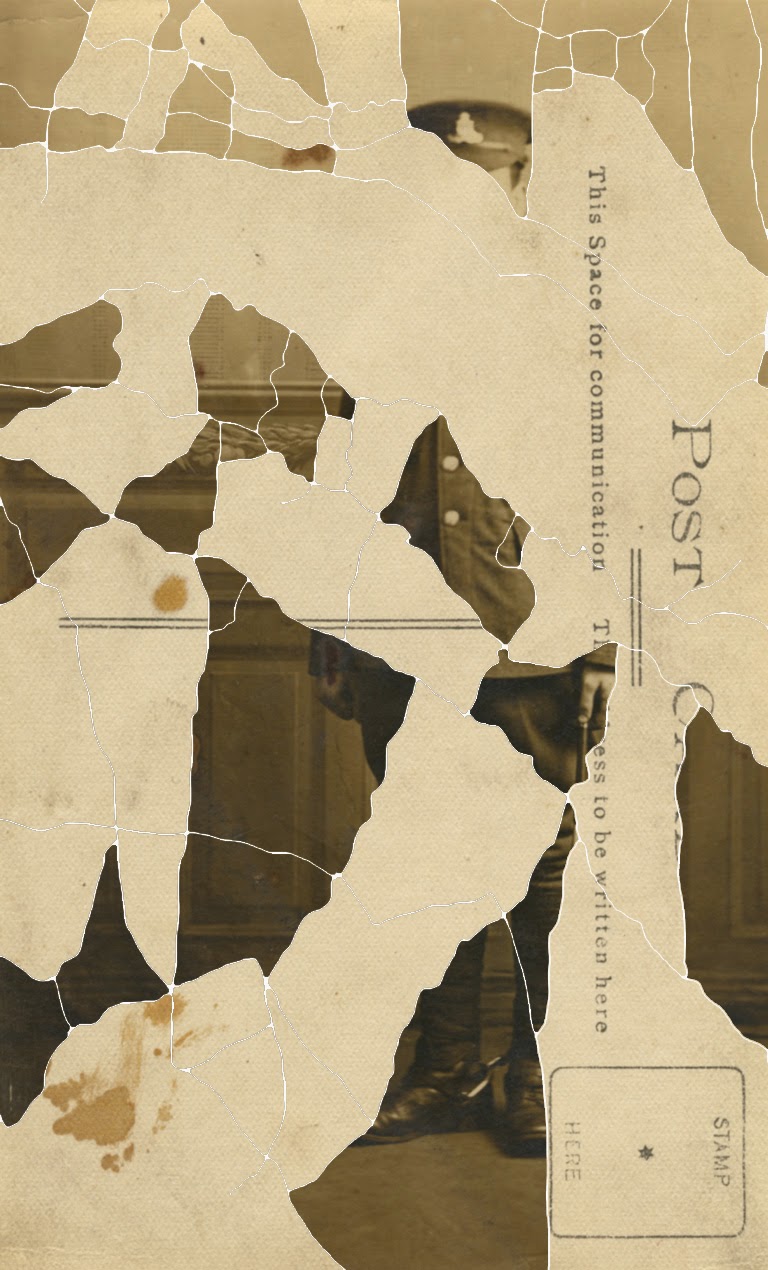

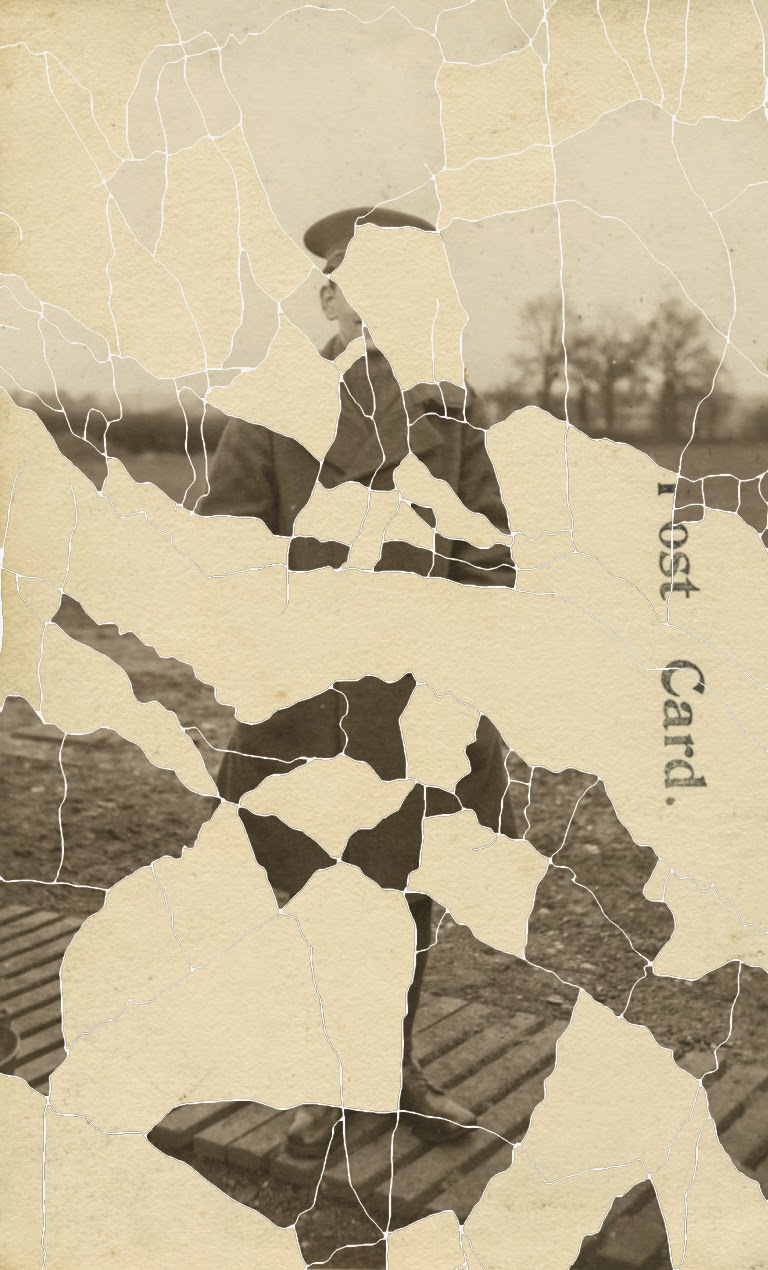

Postcards are a kind of conversation, inasmuch as they’re a connection between two places; one that’s unfamiliar and one that’s known. That’s not always the case of course, but their form’s a framework – a metaphor – with which I try to engage with the past.; to find its lost, anonymous individuals. ‘The Past is a foreign country’, wrote the author L.P. Hartley in the first line of his novel The Go-Between. Whatever information we receive about that place, whether in writing, an object, a painting or a photograph, it comes like a postcard from a foreign shore.

Postcards are fragments, pieces of a world which has vanished, often carrying information of little or no consequence. In the translator’s foreword to The Arcade’s Project, Walter Benjamin’s ‘monumental ruin,’ we read:

“It was not the great men and celebrated events of traditional historiography but rather the ‘refuse’ and ‘detritus’ of history, the half concealed, variegated traces of the daily life of ‘the collective,’ that was to be the object of study.”

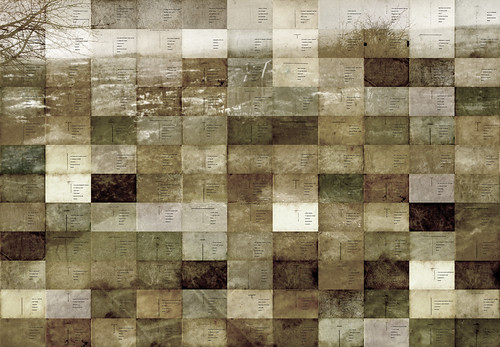

The ‘collective’ is represented in this exhibition by the sheer number of postcards and the pictures which they make when grouped together as a whole. What their component images say, echoes my attempt to find the individual so often subsumed, both in unimaginable numbers and the history which we read in books or know through film and television.

In photographs we often come closest to finding individuals when – ironically – they’re distant, when they’re blurred and unaware of the picture being taken. These are genuine moments of history. With words, it’s often the smallest of details which brings the past alive, for in these parts the whole of the time from which they’re now estranged is immanent.

Tom Phillips, in the preface to his book ‘The Postcard Century’ writes that with postcards:

“High history vies with everyday pleasures and griefs and there are glimpses of all kinds of lives and situations.”

High history sits in every word, even in the ‘x’ of a single kiss. Or the words in the postcard below; prices for Train, Ale and Fags.

A postcard too is often the physical trace of a journey, one connecting the dots from the place in which it was posted to its final destination. But this destination’s never really reached, and as such, a conversation which may have begun 100 years ago, is never finished. We read the words today, written before we’d ever the hope of existing, sent by those who don’t exist anymore.

The images in this exhibition are not ‘genuine’ postcards per se, but they are (for the most part) postcard-sized, inspired by a collection dating from the First World War. It’s the idea of the part (the individual image) as being a part of a whole which interests me and the whole being immanent in the part, just as humanity is immanent in every individual.

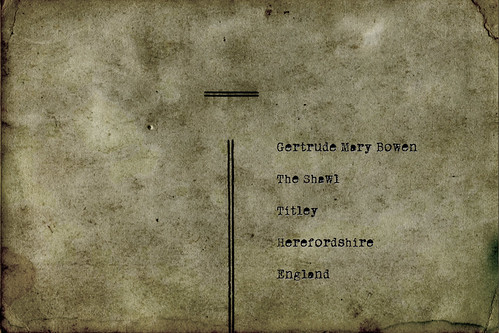

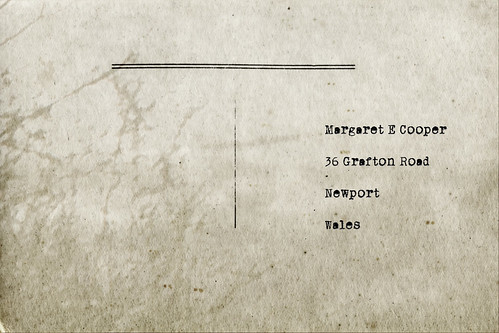

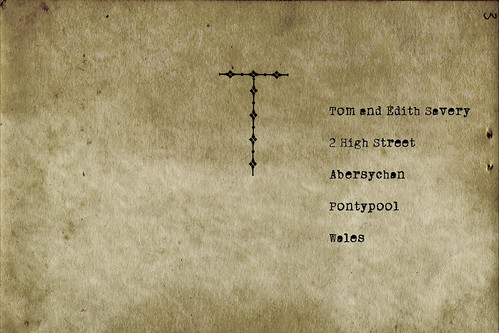

Front and Back Battlefield

Below are examples of the postcards I have made featuring the names and addresses of next-of-kin of men of the 2nd Monmouthshire Battalion who fell in the Fisrt World War. I’m making the work for a conference in Tourist Experiences: Meanings, Motivations, Behaviours at UCLa in April. The first image shows the postcards in their entirety.