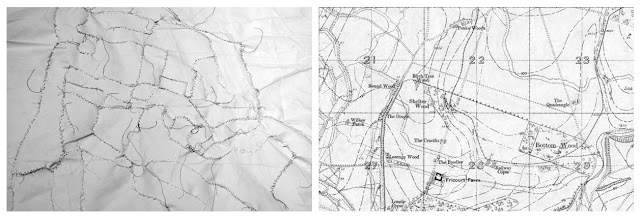

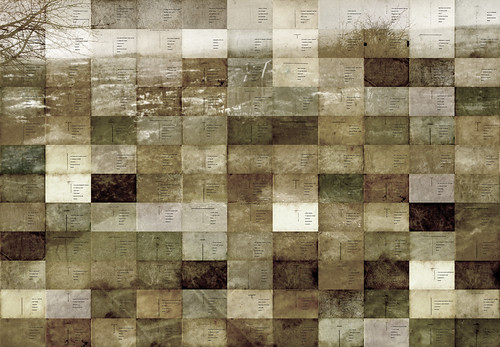

I completed my first three stitched ‘trench maps’ today and have popped them in frames ready to be exhibited in Luxembourg. Ideally they wouldn’t be in frames at all and would be presented on a much large scale, but as first versions go I’m pleased. Certainly I can see how I would like to progress them, adding more layers to create kinds of palimpsests.

Empathy and the First World War (Part 5)

Empathy and the First World War (Part 5)

The backgrounds of these postcards have become of great interest to me in as far as they help elicit a sense of empathy with those who are pictured. Some of the postcards feature no backgrounds at all and are simply headshots which make an empathetic response a little more difficult. What I want to look at here are natural and studio-based backgrounds, examples of which can be found below.

I’ve already discussed windows in old photographs and in the background of the image above one can see a window of one of the houses behind.

I wonder what the same scene would be like if I was standing behind, looking through the net curtains? I’d see the back of the young man being photographed and those who are taking the picture – more proud parents perhaps? I’d watch for a while, then turn my back and return to my own life within the terraced house. It’s imaginative wanderings like this which serve to animate the scene, to remind us that the past was once ‘now’.

I imagine this photograph was taken in the garden of the soldier’s parents’ house. I can imagine them holding this image, just as I’m doing now and walking outside to see that corner of the garden in which he’d been standing. The dilapidated fences, the dirt ground, the trees and the houses behind would all resonate with his presence. If I walk outside into my own garden, with this image in my hand, everything that makes ‘now’ what it is, would serve to animate it. The feel of the wind, the sounds of the birds in the trees, the feel of the ground beneath my feet etc.

This photograph was obviously taken in a studio and whereas in the previous image the backdrop is a real scene, the one above is like something from an 18th century painting. In the foreground we can see bunches of wild flowers growing alongside a quiet country track, leading off through an idealised landscape complete with ‘Rococoesque’ trees, a river and a picturesque bridge. One almost expects the solider to turn away from the incongruous chair and to walk off up the path and out of sight.

With the first image, the domestic backdrop of a garden, its fences, the chicken coup and the backs of neighbours’ houses provides a stark and disturbing contrast with what we know awaited the young man being photographed. This contrast is just as stark in the studio picture above, and in some respects even more disturbing.

Whereas the fictional scene could at least be imagined by the artist, what the man standing before it was about to face on the battlefield would never have been conceivable even with the keenest of imaginations. Reality was in a way even less real than this Arcadian backdrop which seems to depict something akin to Paradise. Perhaps this is why I find this image so haunting?

The reverse of the postcard contains text which reads: To Mr J Wade, With happy memories of past days spent at Waresley House.

I did some research into Waresley House and discovered that it was once the home of both the Peel family (Robert Peel) and the Perrins family of Worcester Sauce fame. A large Georgian pile, I wondered what the soldier did there, who Mr J Wade was and whether or not he was the owner of the house. Having looked at the 1911 census however, I could find no record of Mr Wade. The house was owned by a Mr Gibbons, an 87 year old widower who lived there with his two daughters (both single and aged 49 and 47) and nine domestic servants.

It is possible that Mr Gibbons died soon after 1911 and that Mr Wade took over the house thereafter. Looking for Mr Gibbons on Ancestry, I found him in the same house in 1891 along with 13 children. The cook in 1911, Mary Pugh was also listed.

Empathy and the First World War (Part 4)

Another postcard from my World War One collection:

It’s a rather faded image but we can see that it shows a man standing outside a gate to what looks like the back yard of a house. Like the previous image (see Part 3) the man is dressed in his uniform, ready to head off to war. Or perhaps he’s returned, on leave maybe, about to go back to the Front? We’ll never know, but looking at his face, there’s something about his expression which looks weary at the very least. Of course this is probably reading too much into the picture, but there is something about his face which makes me wonder. To make it easier to see, I’ve enhanced the image a little:

Detail of the soldier’s face:

Like the previous postcard, I can well imagine the scene without the soldier standing there; the feel and the colour of the ivy, the bricks and the old, rather battered door. My imagination colours the image, and through this colouring, the textures of the bricks and the door become apparent. And like the other postcard, it is in itself a tactile object which speaks of the soldier’s absence more than his presence – after all, a postcard is a form of communication sent by someone who is, at the moment, absent from the life of the receiver. Turning it over and looking at the reverse, I could see that it had been addressed to a Miss V. J. Edwards. I wondered if she was the man’s fiancee, but looking at his hands, I could see that he was wearing what appears to be a wedding ring. And again the hands are like those I’ve discussed previously (see Part 1 and Part 3).

Could Miss Edwards be his sister? As I hold the postcard, and turn it over in my hand, I find myself performing an action she herself would have performed. What would she have thought as she read the rather enigmatic text?

1919 16.Puzzle BLA.

I’m assuming that the number at the top is the date (1919) which means we can perhaps also assume the soldier on the front survived the war. Was the photograph itself taken when the war was over? Would that account for his rather tired expression? It seems unlikely, and given the rest of the text, it might be that this isn’t the date at all. Sadly, the franking mark on the stamp isn’t clear enough to tell. What does 16.Puzzle BLA mean? Is it No.16 in a series of puzzles? Is BLA itself the puzzle – a secret code shared between the two; between the soldier and Miss Edwards? Interestingly, in the image itself, we can see in the bottom left hand corner, a notebook on a wooden bench. Did the soldier conceive his puzzles within its pages?

A hand rolled cigarette lays next to it, and the two together serve to animate the image – or rather the soldier in the image; I can picture him smoking, writing in his notebook, in a hand like that on the reverse. Holding the postcard and reading it, I can also ‘animate’ the person to whom it was sent.

With this single image then, a relationship long forgotten has been re-established.

Reading Roads

Introduction

In Wales in 2008 I walked a path along which my great grandfather had walked every day from his home to the mines in which he worked. He died in 1929 (as a consequence of his work) and all I knew of him, before my visit, were what he looked like (from two photographs) and things my grandmother had told me. But on that path I felt I found him on a much deeper level. The feel of the wind, the way the clouds moved, the sound of the trees and the line of the horizon were all things he would have experienced in much the same way. It was as if these elements had combined to ‘remember’ him to me.

As a consequence of my walk, the line which linked us on my genealogical chart changed to become instead a path, for when I follow lines in my family tree from one ancestor to the next and find myself at the end, so that path in Wales had led to my being born. That path on which I walked for the very first time, was as much a part of who I was as my great grandfather: “places belong to our bodies and our bodies belong to these places.” [i]

Roads (paths, tracks and traces) have become an important part of my research and it was whilst reading Edward Thomas’ poem Roads that I found connections between what he had written and what I was thinking. I’ve reproduced the poem below, and where necessary added my thoughts.

Roads by Edward Thomas (1878-1917)

I love roads:

The goddesses that dwell

Far along invisible

Are my favourite gods.

Roads go on

While we forget, and are

Forgotten like a star

That shoots and is gone.

The reference to stars (or a star) in this verse, reminds me of a quote (to which I often refer) from Roland Barthes’ book Camera Lucida, in which he writes:

“From a real body, which was there, proceed radiations which ultimately touch me, who am here; the duration of the transmission is insignificant; the photograph of the missing being as Sontag says, will touch me like the delayed rays of a star. A sort of umbilical cord links the body of the photographed thing to my gaze – light though impalpable, is here a carnal medium, a skin I share with anyone who has been photographed.”

On this earth ’tis sure

We men have not made

Anything that doth fade

So soon, so long endure:

The hill road wet with rain

In the sun would not gleam

Like a winding stream

If we trod it not again.

They are lonely

While we sleep, lonelier

For lack of the traveller

Who is now a dream only.

From dawn’s twilight

And all the clouds like sheep

On the mountains of sleep

They wind into the night.

The next turn may reveal

Heaven: upon the crest

The close pine clump, at rest

And black, may Hell conceal.

Often footsore, never

Yet of the road I weary,

Though long and steep and dreary,

As it winds on for ever.

Helen of the roads,

The mountain ways of Wales

And the Mabinogion* tales

Is one of the true gods,

(*In the tale of Lludd and Lleuelys from the Mabinogion, you will find the following text: “Some time after that, Lludd had the island measured in length and breadth; the middle point was found to be in Oxford. There he had the earth dug up, and in that hole he put a vat full of the best mead that could be made, with a silk veil over the surface. He himself stood watch that night.” I discovered this passage whilst researching my Welsh ancestry, and being as I am from Oxford, found it rather appealing.)

Abiding in the trees,

The threes and fours so wise,

The larger companies,

That by the roadside be,

And beneath the rafter

Else uninhabited

Excepting by the dead;

And it is her laughter

At morn and night I hear

When the thrush cock sings

Bright irrelevant things,

And when the chanticleer

Calls back to their own night

Troops that make loneliness

With their light footsteps’ press,

As Helen’s own are light.

Now all roads lead to France

And heavy is the tread

Of the living; but the dead

Returning lightly dance:

Whatever the road bring

To me or take from me,

They keep me company

With their pattering,

Crowding the solitude

Of the loops over the downs,

Hushing the roar of towns

And their brief multitude.

Two Soldiers

I was once given a collection of 200 World War I postcards featuring portraits of soldiers and have always wanted to trace some of those featured. Through research on the National Archives website and through deciphering rather bad handwriting I discovered that the man immediately below is one Walter Henry Chevalier who served in the Army Service Corps and Northumberland Fusiliers. I think, if my research is correct, that he survived the war, dying in 1962 aged 64.

Below, another World War I soldier and another survivor. The rather splendid surname ‘Dangerfield’ is written on the back and having searched for him and got over 100 Dangerfields I had a closer look at the image. The spurs and the crop suggest of course something to do with horses and the cap badge as far as I can see is that of the Royal Horse Artillery. Having refined my search, I found Edward Paul Dangerfield, Second Lieutenant in the Royal Horse Artillery. Again, if my research is correct, he survived the war and died in 1978.

Empathy and the First World War (Part 3)

It’s hard to tell where this image was taken, whether in a garden or a public park, but clearly it shows a young man in his new army uniform about to head to war. He stands to attention, albeit somewhat awkwardly, staring into the camera – almost through it, into the distance. I wonder as I look at him who is on the other side taking the photograph? A proud parent perhaps, an anxious one? A friend or maybe some other relative? The young man in question would, I imagine, have left soon after the image was taken and the question is there to be asked: would they – whoever it was – have seen him again? Behind him a tangle of brambles foreshadows the barbed wire entanglements laid out in front of the trenches, wire on which so many like this young man lost their lives.

As with the previous images I’ve discussed (see Empathy and the First World War Part 1 and Part 2) I’m interested in how I can find a way of empathising with this individual, a young man whose name has been lost and who, for all I know, exists only within the image on this postcard. The difference between this ‘image’ and those discussed previously are that this is a physical object – a postcard; one of a number printed as keepsakes. However, as I look at it, I try as I do with other photographs to imagine the moment in which it was taken. I imagine the click of the camera , satisfied comments from the photographer, after which the young man picks up his cap, puts it on and walks off down the path. The crunch of footsteps dissipates along with the voices and I am for that moment left standing looking at the brambles and the undergrowth.

For some reason it’s hard for me to visualise this young man in colour – there’s something in his face which prevents me from seeing him talk. But without him there I can picture the rest of the scene easily enough in colour; I can see the colour of the bricks, the undergrowth and the path. I can see the leaves move and then imagine myself moving, turning and seeing people walking in the distance. I can hear sounds – birds and so on, perhaps because I can hear them outside my window on what is a beautiful spring-like day. It’s a photograph which depicts the presence of the young man in the picture and yet speaks of his absence, which is of course hardly surprising given that it was taken almost 100 years ago. Whether he survived the war or not he’s going to be absent from the world today.

The way in which I hold the postcard and look at the image is important, for it no doubt echoes that of those who knew him, who whilst he was away looked at the image and remembered their friend or loved one; someone who was present in their minds and yet absent from their immediate world.

On the reverse are the words ‘POST CARD’ and a ‘T’ shaped divide between correspondence and address. The postcard itself is blank, save for the 15p pencilled in the corner – the apparent monetary value of the image. I’ve worked before on the idea of the ‘T’ shape as being like a makeshift grave-marker and having looked at the photograph on the other side and having imagined him walking away – leaving just the image of the brambles – it becomes all the more poignant. There is no message, no address. Just ’15p’.

When looking at the previous images (see Empathy and the First World War Part 1 and Part 2) there was one moment with which I could attempt to empathise – that being when the image was captured, but with the postcard there are many more which I can narrow down to two, one specific, the other more general. The first of course is again when the image was taken, the second an amalgamation of all the times it was handled, held between two hands just as I’ve been holding it today. The postcard, as an object, fits physically into a sequence of ‘gestures’, a moment in which the stark boundary between now and then – as described when a photograph is taken – is blurred. Empathy in this respect is not necessarily with the young man, but with those who remembered him; not with the man within the image, but with those who held the image.

Thinking about my hands holding the postcard, turning it round now, I find myself looking at the young man’s hands hanging at his side. They remind me of the hands of the corpse in the first image I looked at (see Part 1) and again an empathetic link is established. I wrote earlier how I found it hard to imagine his face moving in any way – it seems definitively frozen by the camera – and yet looking at his hands the opposite is true. I can well imagine them twitching nervously, unsure of what to do as he stands to attention.

I think too of the grass in the second image (see Part 2) growing over the turned earth and can well imagine the brambles behind the man doing the same.

I’ve written before how empathy is a kind of feedback loop, where our own bodily experience is influenced by our knowledge and vice-versa, growing all the while so that bodily experience influences knowledge whether, in the case of this subject, standing on a battlefield or looking at a photograph. I can see this loop working as regards the images I’ve discussed so far, how empathy accumulates slowly over time.

Empathy and the First World War (Part 1)

Windmill Military Cemetery, Monchy le Preux, east of Arras, 1918

The shadow figure of a survivor reflecting at the side of a grave is the image of the Great War and while these men are not quite silhouettes, they are nonetheless unknowable, just like the dead next to whom they stand. In Brook’s iconographic photo the silhouetted man and the corpse are one and the same thing, as if the dead man’s shadow, is for a time, living a while longer. There is then little to divide the four men and the two on either side from those over whom they stand, just as throughout the war, the gap between life and death could be measured by the thickness of a cigarette paper.

New Marston War Memorial Names

At the bottom of my street is a War Memorial such as you find in most towns and villages throughout the country. I’ve walked past the memorial many, many times and while I’ve often thought of those who died in both World Wars, I’d never before read its list of people. Therefore, this week I did just that and have spent time researching where they died and where they’re now buried.

A couple of details at once stood out : A G Akers, the first on the list, lived in my road and died of wounds on the last day of the war; 11th November 1918. Arthur Gerald Harley was killed in action, aged 21 on 1st July 1916 – the infamous first day of the Battle of the Somme.

I will endeavour to find out as much as I can about some of those who are commemorated on this memorial, in the meantime the following list is what I’ve so far discovered:

Canvas and Trench Map

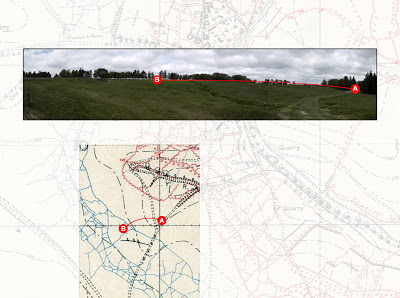

Trench Panoramas

There is something aesthetically beautiful about photographs taken of the Western Front during World War One. It might sound a strange thing to say, but it’s not unlike the view I have of those photographs taken by the Czechoslovak Secret Police in Prague. Although taken in very different circumstances, they are nonetheless about observation – secret observation of a perceived or definite enemy.

The photograph below is one of those panoramas, taken in Serre during the First World War. (I do not have permission to reproduce the image so have shown it below in no great detail.)

The fact I find these images so aesthetically pleasing is perhaps a reminder of the distance between myself and the subject. These images, it goes without saying, were not taken for their aesthetic appeal. These were images designed to better enable armies to deliver death to the enemy.

I wanted somehow to use this look in creating panormas of fake landscapes based on places to which I’ve been and the work I’ve made as part of my Mine the Mountain series, in particular, The Past is a Foreign Country which is shown below.

Alongside this work, I will, at the next Mine the Mountain exhibition, show a series of landscape photographs taken on trips around Europe, such as the two below.

I wanted to show that although the past as we perceive it is in some respects a fiction (in that it can only be imagined) it was nonetheless real – that what happened did so in what was then the present. Taking the aesthetic of the panorama above therefore, I’ve created an amalgma of the landscapes, making a single panorama. It’s not a finished piece by any means, but the start of a new line of work.

Beaumont Hamel

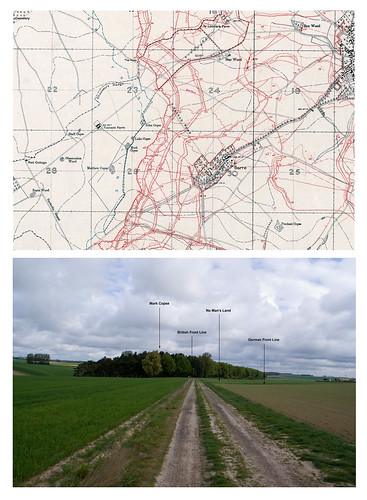

Battle of the Somme – Serre

First image is a detail from a Trench Map (1916) showing Serre, the German Front Line and trenches (red) with the British Front line in blue. The photograph below shows Mark Copse, from where the 11th Battalion East Lancashire Regiment went over the top on 1st July 1916 suffering horrendous casualties as a result.

The Somme

“Frontiers are lines. Millions of men are dead because of these lines.”

Georges Perec

The name Somme is, in the minds of many, synonymous with death, a byword for futile and indiscriminate slaughter. Think of the Somme and the image of men walking towards their deaths comes to mind. Think of the Somme and one date stands out above all others; 1st July 1916, the day the battle began. The battle itself lasted over four months, up until November 18th, but the 1st July is as infamous a date as any, being as it is the blackest day in British Military History. By the end of the first day’s fighting, British and Commonwealth forces had lost almost 60,000 men, with 20,000 of those killed or missing in action – a number which is almost impossible to comprehend. The exact number of casualties over the entire course of the battle (1st July – 18th November 1916) is unknown, but Allied forces lost some 620,000 men with over 145,000 killed or missing in action. Germany suffered around 465,000 casualties with almost 165,000 of those killed or missing.

These numbers are of course horrendous, but there’s always a danger that statistics such as these will only ever be numbers, rather than a single death multiplied several thousand times. Every one of those over 300,000 killed or missing in action was a son, husband or brother; an individual whose life was cut short for a small patch of ground. And we mustn’t forget the wounded whose injuries were often appalling – the result of a new type of warfare, where bodies were mauled and mangled by artillery shells, machine gun fire and shrapnel. Disfigurements and mental illness meant that even if they were lucky enough to return, many would never again lead a normal life.

Before visiting the battlefields, I recorded my thoughts on how I imagined the Somme. Drawing on old photographs, books I’ve read and contemporaneous records, I’d built up a picture – a collage of sorts – of devastated fields, cut through with trenches; craters and mud, machine gun fire and shells. I’d imagined woods reduced to spent matchsticks occupying a space on the horizon and the terrain as I saw it in my mind’s eye was almost always flat. The images themselves were silent, equivocal and without any weight or real sense of place. There was colour but like any specific detail the colours were always vague. Any imagined scene was removed from my senses. I could try to imagine the war, but of course any idea as to what it was like would – to say the very least – be well wide of the mark. I could imagine the rain, the blue sky, the smell of the grass, but still it was all divorced from my senses; an indeterminate collection of images wherein there was little sense of direction. I could try and imagine movement, but any progression derived only from a series of stills as if I was looking down a length of film found on a cutting-room floor.

Having arrived in the Somme, we drove towards our B&B, down the narrow roads which cut across the fields. The sun was setting, casting long shadows which lay down across the landscape like discarded coats and clothes. I couldn’t help but think of those who’d stood in the trenches on the morning of 1st July 1916, knowing they might never see another sunset again. For a moment, this sunset became the one they wouldn’t to see. The sunset of that terrible day.

On arriving at the B&B we found our first cemetery.

We had just over a day to explore the Somme battlefields and therefore took the ‘Circuit of Remembrance’ a route signposted with poppies which takes in the major sites of the battle. Starting at Beaumont Hamel, we travelled to Thiepval, Pozières, Longueval, Rancourt, Peronne and La Boiselle. The following morning, we travelled to Serre to see the place where, among others, the Accrington Pals suffered horrific losses on that first terrible day.

Travelling through the countryside and seeing signposts pointing the way to villages and towns such as Arras, Pozières and Thiepval, I felt a strange sensation, in that prior to visiting the Somme, these legendary names were almost fictions – places connected with a distant past found only in the pages of history. Temporal distance in some way then correlates with geographic distance, where places one has never been are like those times to which one can never go. It’s as if they are names of moments in time rather than places in another country; the past is indeed a foreign country, and yet one it seems can go there.

Of all the places we visited along the ‘Circuit of Remembrance,’ two stand out in particular; the site of the attack on Serre at what is now The Sheffield Memorial Park, and the Newfoundland Memorial Park at Beaumont-Hamel. Of course all other sites were extremely poignant, not least the Memorial to the Missing at Thiepval and the many cemeteries, all immaculately kept, which are found throughout the Somme countryside.

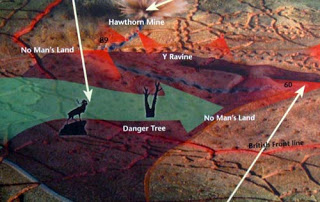

The first place we visited was the Newfoundland Memorial Park at Beaumont Hamel.

It’s one of the few sites in the Somme region where the ground has remained largely untouched since the end of the First World War. The trenches are still visible, for example, St. John’s Road and Uxbridge Road which once led to Hyde Park Corner and Constitution Hill; trenches now filled in beneath a field of Rape (the line of the Uxbridge Road trench has been marked in white in the car park).

The naming of the trenches has always interested me. It’s almost as if in the midst of the ruined landscape, whose pre-war character had all but been effaced, a new place was brought into being; not simply a ruin of that pre-existing world, but a new world entirely; a labyrinth of lines cut into the ground, named after streets or towns back home. It’s as if these ‘streets’, ‘lanes’ and ‘alleys’ were each a piece of the collective memory of those who fought and died there; fragments of a place called ‘home’ to which many would never return. Now of course the trenches have all but disappeared along with the men who made them, along with their individual memories. And yet they remain on maps and in books, and although the ruined towns and villages have been rebuilt, their own much older names seem to belong more to this other lost world than that before or after.

It was at Beaumont Hamel that the Newfoundland Regiment attacked on 1st July 1916, suffering as they did appalling losses. The following description is taken from the ‘Newfoundland and the Great War’ website:

“Thus it was that the Newfoundlanders moved off on their own at 9:15 a.m., their objective the first and second line of enemy trenches, some 650 to 900 metres away. In magnificent order, practiced many times before, they moved down the exposed slope towards No Man’s Land, the rear sections waiting until those forward reached the required 40-metre distance ahead…

…No friendly artillery fire covered the advance. A murderous cross-fire cut across the advancing columns and men began to drop, at first not many but then in large numbers as they approached the first gaps in their own wire. Private Anthony Stacey, who watched the carnage from a forward trench with Lieutenant-Colonel Hadow, stated that “men were mown down in waves,” and the gaps cut the night before were “a proper trap for our boys as the enemy just set the sights of the machine guns on the gaps in the barbed wire and fired”. Doggedly, the survivors continued on towards The Danger Tree.”

The ‘Danger Tree’ still stands, and standing there today, looking at the sheep laying around its base, it’s hard to imagine the scene at that same place 96 years ago.

Like many who’ve read about the Somme, I was aware how close the opposing armies were to one another – at least in terms of stats – separated as they were by the void of No Man’s Land, but it was only in this place that the distance was made startlingly apparent; it was hardly any distance at all. Entering the memorial, one can see the British front lines. A leaflet guides you around and suddenly, you find yourself looking back from the German front line towards where you entered, a distance which is all but a few minutes’ walk away. And in between is a patch of ground, much like any other you might have seen before but upon which thousands lost their lives.

The following images show the Caribou Monument to the Newfoundland Regiment (shown on the map above) which stood at the British Front Line. The Danger Tree is that shown above which marked the furthest many men managed to get. The Y-Ravine is behind the German Front Line, the trenches of which are also shown below.

Of course it goes without saying that in 1916, the ground would have looked very different. Pockmarked by shells, cut through with trenches running on for miles and covered with swathes of barbed wire it would have presented advancing troops with considerable difficulties even without the horrors of enfilading machine gun fire and pounding artillery.

As far as can be ascertained, 22 officers and 758 other ranks were directly involved in the advance that day. Of these, all the officers and around 650 other ranks became casualties. Of the 780 men who went forward about 110 survived unscathed, of whom only 68 were available for roll call the following day. To all intents and purposes the Newfoundland Regiment had been wiped out, the unit as a whole having suffered a casualty rate of approximately 90%.

It goes without saying that as tourists today we can never imagine what it was like to be a part of this battle, not that we should be deterred from trying. Even so, one can appreciate things which sharpen the focus of any prior knowledge of the war and in particular any images which one might have imagined beforehand. I’d read about the attack on Beaumont Hamel in a book by Peter Hart and had imagined a vague collection of ‘ambiguous stills’ with which I did my best to appreciate the experiences of those who suffered the appalling violence of that first day. But standing in the middle of what had been No Man’s Land, with the British Front Line to my left, beside the Newfoundland Caribou Memorial, and the German Front Line to my right – just behind the memorial to the 51st Highland Division – I was struck by how small the battlefield, at that position, was. As I’ve said, if this was any place in the countryside, it would constitute nothing more than a small part of a short walk, but in 1916 it was a great advance, in the pursuit of which, many thousands lost their lives.

There is a tendency at sites such as this, or rather in associated museums (for example that in Ypres) to create recreations of battles with sounds effects, waxworks, lighting effects and so on. For me, such recreations do nothing other than turn history into fantasy. They push history – which already borders on fiction (in that it can only be imagined) – deeper into the world of make-believe. Recreations serve no other purpose than to ‘entertain’ and certainly do little by way of justice to memory of the men who fought there. It’s much better to be in a place, to hear the birds and see the trees… they might not be shells or machine guns, but they are real all the same.

I must admit I could have stood there in ‘No Man’s Land’ for hours, collecting together what I knew of the war and what I could glean from the guide and anchoring it to the reality of the world by which I was surrounded. What I could really appreciate here was the terrain, not only the pock-marked surface, but the level of the ground which, superficially at least, appeared quite ‘flat’. Certainly, if one was out walking, one wouldn’t think it was particularly steep or hilly. However, from the point of view of those who left the British Front Line to attack the Germans, one could see what they were up against. The ground rose just enough to leave them exposed, while at the same time affording the German army at least a degree of shelter. Indeed, something which I found myself coming to understand in the Somme, were the subtle shifts of the terrain and how such changes, visible to the individual eye, shaped the war as a whole and determined the fates of so many hundreds of thousands of men.

The image below is taken in what was No Man’s Land. The Y Ravine Cemetery is on the right. Over the ridge in the distance is the German Front Line.

Over the course of the last few years, ever since my visit to Auschwitz, I’ve tried to understand what it is about being in a particular place that makes knowledge of a past associated with that place so much more compelling. It seems obvious that it should be the case, but why? I can watch countless DVDs about the Somme for example, view masses of photographs, read the testimonies of those who fought and look at the lists of the names of the dead. But only by standing there, in the middle of a field (upon which sheep were grazing) did the full horror make itself known.

I felt exactly the same thing at the Sheffield Memorial Park, situated on what was once the British Front Line between ‘Matthew Copse’ and ‘Mark Copse’ near the village of Serre. It was from here that an attack was made on what was then a fortified village by, amongst others, the Accrington Pals and Sheffield City Battalions, again on that infamous day, 1st July, 1916.

Again, staring ahead towards the Queens Cemetery, behind which the German Front Line would have run, one could see just how close the two sides were to one another. One could also read the terrain and see the advantage the Germans had when facing the approaching army. As a result therefore, one could also see just what the soldiers of the Pals Battalions were up against, even without the horrors of machine guns and artillery.

Again I have to stress, that we can never fully appreciate what the men who climbed from their trenches faced that fateful day. But as with my experience at the Newfoundland Memorial, I found that in looking towards where the German lines would have run, across the field over which the soldiers would have walked, the horrors of which I’d read became much clearer. I couldn’t see the guns of course, or the artillery and barbed-wire. I wasn’t walking into a hail of bullets with shrapnel flying from shells bursting all around me. But there in the tranquility of the present day, where one could hear the birds, I’d brought with me to that place, the whole of my existence – my past – and that was something at least I had in common with the brave men who fought there.

In La Boiselle, one can find the Lochnagar Crater, caused by a huge mine detonated at 7.28am on 1st July 1916. Containing 24 tons of explosives, it was at the time the largest ever man-made explosion.

At 300 feet in diameter and 70 feet deep, the crater is still the largest caused by man in anger. Again, like the various battlefield sites, it’s a tranquil place, in stark contrast to the violence from which it was created. And yet, although one can’t hear the noise, one can see it in the vast space left in the ground. The sound has left a footprint; it’s become physical, just as sounds remain in the pock-marked battlefields found across the Somme.

In some respects, this idea of a ‘sonic footprint’ is akin to that of people leaving a trace on paths, roads, tracks and other lines found in the landscape. The trenches for example – those which one can see today – are not as they were in 1916 (i.e. they’re not as deep and are grown over with grass) but they are lines created by people many years ago. They might not call to mind a sound in quite the same way as the Lochnagar crater, but they’re nonetheless records of actions and movements.

In his book, ‘Lines, A Brief History’, anthropologist Tim Ingold writes that human beings, ‘leave reductive traces in the landscape, through frequent movement along the same route’. He considers this in light of the etymology of the word writing (derived from the Old English term writan – meaning to incise runic letters in stone) and surmises that human beings somehow ‘write’ themselves in the landscape. Henri Bergson wrote that our whole psychical existence was something just like a single sentence. I believe,’ he said, ‘that our whole past still exists.’ The whole past could be said to exist, upon and within these trenches, as ‘sentences’, ‘written’ in the landscape by men almost 100 years ago.

These lines can also – metaphorically speaking – be thought of as magnetic tapes, where as we walk, we record our presence; where what we see, hear, touch etc. at any given moment, is analogous to the recording head of a tape-player arranging the magnetic particles so as to record the sound or video image. Equally, when we walk down a particular street, path or track, we simultaneously play-back previous recordings, those laid down by people long since lost to the past and the battlefields of the Somme are a perfect place to illustrate this point.

At the battle for Serre on that fateful day – 1st July 1916, hundreds of men lost their lives on the ground between the village and the memorial where we were standing. The weather on the day of our visit was mixed, but mostly dry (the battle took place on a beautiful summer’s day). There were patches of blue sky and the odd cloud. Looking ahead, I could see the lie of the land. I could see the distance, the village of Serre and behind me the trees of the copse. I could hear the birds and feel the ground beneath my feet. Imagine then, that as I walked, the things I saw were somehow recorded in the ground upon which I was walking: the position of the sun, the colour of the sky, the sound of the birds and the distance. As a record-head receives information and translates it onto tape, so metaphorically, my body was doing the same.

Of course, recording-heads don’t just record, but play-back all that’s previously been recorded. Again we can think of the ground as being crossed by many lines and that along every one of those lines are hundreds of ‘recordings’ left by those who went before us. We can imagine that what they saw, what they heard and what they thought were all translated into the ground upon which they walked.

It was Bill Viola who said that ‘we have been living this same moment ever since we were conceived. It is memory, and to some extent sleep, that gives the impression of a life of discrete parts, periods or sections, of certain times or highlights’. If we think of the lines the soldiers left behind, lines which stopped abruptly in No Man’s Land, we can imagine them leading all the way back to the time they were born.

These long, individual lines are of course impossible for us to imagine in their entirety, but on sites such as the battlefields at Serre and Beaumont Hamel, where the lines of trenches can still be seen and where No Man’s Land stretches out ahead, we can be sure at least of seeing a small part. By following these fragmentary lines, our bodies in a very small way mirror that of the soldiers. Again I have to stress the words very small way and again make it clear that we can never know what it was like to experience what they did.

When we walk down the line of a trench, the gestures of our bodies are bound in some very small way to mirror those of people caught in the midst of war. When we look at the sky, down at our feet, turn our heads left or right, we can assume that an aspect of the way our bodies move is almost a mirror-image of those who went before us. We can imagine then, that when we plant a footstep, the way our body moves, what we see around us is akin to the idea of our bodies playing back that which has been recorded in the ground; the ground determines how we move – determines the shape of our body; thus we empathise kinaesthetically with those lost to the past.

These lines, as I’ve said, are only fractions of the total line carried by men into battle, i.e. the total span comprising the entire geography of their lives. But history is full of holes, and the gaps have holes of their own.

History tells us only a little about the past. It gives us the outline whereas the rest is all but missing. The history of an event, as told in a book, has a beginning, a middle and an end, but of course in reality the past is never like that. Historic events are about the people involved, many of whom are missed out altogether. For George Lukács, ‘the “world-historical individual” must never be the protagonist of the historical novel, but only viewed from afar, by the average or mediocre witness.’ In other words, those historic events written about in books, are best discovered through the eyes of those who are missing from the text, people who at best are either given the epithet ‘mob’ or ‘masses’ or are bundled into numbers and tables of statistics. It’s through the eyes of these people that I want to see the past.

To consider this a little further; in the film Jurassic Park, the visitors to the Park are shown an animated film, which explains how the Park’s scientists created the dinosaurs. DNA, they explain, is extracted from mosquitoes trapped in amber and where there are gaps in the code sequence, so the gaps are filled with the DNA of frogs; the past is in effect brought back to life with fragments of the past and parts of the modern, living world. This ‘filling in the gaps’ is exactly what I have done throughout my life when trying to imagine the past and it’s just what we do in terms of the fragments of lines upon which we can kinaesthetically engage with people lost to the past. Where there are gaps we use our own lives to fill the holes and thereby understand that those who died in places like the Somme, were people just the same as ourselves.

Something else which plays a key role in interpreting landscapes such as those at the Somme is something which we might describe as ‘Embodied Imagination.’ We all at some point in our lives try to imagine the past whether through photographs, paintings or literature, but what we imagine always comprises snapshots, static images animated to some degree by our imaginations. It’s exactly how I described my thoughts on the Somme before my visit.

“Before visiting the battlefields, I wanted to record how I imagined the Somme. Old photographs, books and contemporaneous records all made a picture – a collage of sorts, comprising devastated fields, cut through with networks of trenches. Craters and mud; machine gun fire and shells. Woods reduced to spent matchsticks occupying a space on the horizon. The terrain as I’d imagined it was always flat and the images themselves silent, equivocal, without any weight or sense of place. There was colour but like any specific detail it was always vague. Any imagined scene was removed from my senses. I could try to imagine the war, but of course any idea as to what it was like would be well wide of the mark to say the very least. I could imagine the rain, the blue sky, the smell of the grass, but still it was all divorced from my senses; an indeterminate collection of images wherein there was little sense of direction. I could try and imagine movement, but any progression derived from a series of stills as if I was looking down a length of film found on a cutting-room floor.”

In his book ‘The Materiality of Stone: Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology,’ Christopher Tilley writes:

“At the basis of all, even the most abstract knowledge is the sensuous, sensing and sensed body in which all experience is embodied: subjectivity is physical… The body carries time into the experience of place and landscape. Any moment of lived experience is thus orientated by and toward the past, a fusion of the two. Past and present fold in upon each other. The past influences the present and the present rearticulates the past.”

In a ‘Phenomenology of Landscape,’ he writes: “Knowledge of place stems from human experiences, feeling and thought.”

We could say therefore that knowledge of the Serre battlefield, for example, stems from ‘human experiences’ (the experiences of those who fought in 1916), ‘feeling’ (my own kinaesthetic experience of the battlefield in the present day) and ‘thought’ (my embodied imagination where my knowledge of past human experience is animated by my own kinaesthetic experience). Knowledge of a place is both geography and biography, of both the place and the individual.

Again, Christopher Tilley’s work is useful here. In his book, ‘Body and Image,’ he writes:

“What the body does in relation to imagery [landscape], its motions, its postures, how that imagery [landscape] is sensed through the fingers or the ear or the nose, as much as through the organ of the eye, actively constitutes the mute significance of imagery [landscape] which to have its kinaesthetic impact does not automatically require translation into either thoughts or meanings. The kinaesthetic significance of imagery [landscape] is thus visceral. It works through the muscles and ligaments, through physical actions and postures which provide affordances for the perceptual apparatus of the body in relation to which meaning may be grafted on, or attached. Meaning is derived from and through the flesh, not a cognitive precipitate of the mind without a body, or a body without organs.”

The ‘perceptual apparatus of the body’ as described by Tilley is akin to what I’ve described as my kinaesthetic experience of the battlefield. ‘Meaning’ can then be ‘grafted on’ or ‘attached’, where that meaning is my knowledge of past human experience. The whole is what I’ve described as ‘embodied imagination.’ But we must be careful not to reduce experience down to a mind/body dualism. The mind is not divorced from the body, neither is the body separate from the mind. ‘Consciousness is corporeal.’

I mentioned earlier the names of the trenches; the fact that for four years, a strange, new and violent place was imposed upon a peaceful agricultural landscape; how it’s almost as if the names of the trenches were fragments of the collective memory of those who dug and occupied them. Today, when we walk along what remains, we engage kinaesthetically with those who knew them during the war and we carry with us the entire geography of our existence, stretching back in a line to the day we were born. In effect, we impose – just as we’ve done throughout our lives – our own world upon that which already exists. “In a fundamental way,” writes Christopher Tilley, “names create landscapes” and in a sense, the names of those we have known, whether throughout our lives or for a few minutes are mixed with the names of streets, cities and buildings, to make a landscape unique to us as individuals. The landscape of the Somme, in the physical present or in books and maps has been created not only by the names which existed prior to the war, but by the names of the trenches, fortifications and not least the names of everyone who fell here.

Inevitably in a place such as the battlefield at Serre where so may men fell on that small patch of ground, one’s thoughts will turn to death – the literal end of the line. In an interview in 1979 with Frank Venaille, writer Georges Perec was asked: “…don’t you think that… the determination to work from memories or from the memory, is the will above all to stand out against death, against silence?”

If we can empathise kinaesthetically with the lives of the men who fought, it’s almost inevitable that we will somehow engage with their deaths which inevitably means a contemplation of our own, and in that sense, the fact that we can then walk away means that to some extent we do indeed stand out against death and silence.

Death is at its most visible in the cemeteries and monuments of the Somme. The landscape is covered with hundreds. Immaculate and maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, they are strangely beautiful places wherein one’s breath is always taken away by the row upon row of white headstones. It’s only here the scale of the slaughter becomes apparent. Some headstones have names, many – where names are unknown – have just the words A Solider of the Great War. Often the date is familiar, coinciding with the start of a phase in the battle, July 1st 1916 for example. But many men too vanished altogether and over 72,000 of these men are commemorated on the Thiepval memorial to the missing.

In some respects, by being in the places where they fell, by walking the lines of the trenches and through ‘reading’ or ‘playing-back’ ‘recordings’ in the lines which cover the Somme as I’ve described above, we are, kinaesthetically, remembering the missing and all who never returned home. People are places and places are people. Remembrance is not an act solely of the mind, but of an embodied imagination.

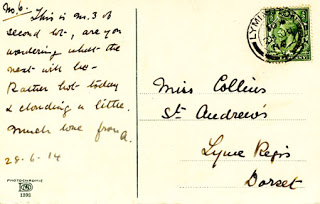

A Poignant Postcard

As part of my forthcoming exhibition, I’ve been purchasing a few postcards for a piece of work, one which mirrors previous works I’ve made with postcards of World War One soldiers. One of my recent acquisitions can be found below.

The postcard shows a quiet, tranquil beach scene, which when one looks at the reverse becomes particularly poignant.

It was posted in the summer of 1914, just a few weeks before the outbreak of World War One. What’s more, the date at the bottom, 28th June 1914, is the date that Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir apparent to the Austro-Hungarian throne was assassinated in Sarajevo.

8th May

The following is a painting by Fred Roe (1864-1947) entitled The Eighth May which shows a scene from the Battle of Frezenberg Ridge, which took place on 8th May 1915 in what was to become known as the Second Battle of Ypres. My great-great-uncle, Jonah Rogers was killed that day near the farm depicted in the painting.

The painting is in the collection of Newport Museum and Art Gallery.

Mine the Mountain 2

Postcards are a kind of conversation, inasmuch as they’re a connection between two places; one that’s unfamiliar and one that’s known. That’s not always the case of course, but their form’s a framework – a metaphor – with which I try to engage with the past.; to find its lost, anonymous individuals. ‘The Past is a foreign country’, wrote the author L.P. Hartley in the first line of his novel The Go-Between. Whatever information we receive about that place, whether in writing, an object, a painting or a photograph, it comes like a postcard from a foreign shore.

Postcards are fragments, pieces of a world which has vanished, often carrying information of little or no consequence. In the translator’s foreword to The Arcade’s Project, Walter Benjamin’s ‘monumental ruin,’ we read:

“It was not the great men and celebrated events of traditional historiography but rather the ‘refuse’ and ‘detritus’ of history, the half concealed, variegated traces of the daily life of ‘the collective,’ that was to be the object of study.”

The ‘collective’ is represented in this exhibition by the sheer number of postcards and the pictures which they make when grouped together as a whole. What their component images say, echoes my attempt to find the individual so often subsumed, both in unimaginable numbers and the history which we read in books or know through film and television.

In photographs we often come closest to finding individuals when – ironically – they’re distant, when they’re blurred and unaware of the picture being taken. These are genuine moments of history. With words, it’s often the smallest of details which brings the past alive, for in these parts the whole of the time from which they’re now estranged is immanent.

Tom Phillips, in the preface to his book ‘The Postcard Century’ writes that with postcards:

“High history vies with everyday pleasures and griefs and there are glimpses of all kinds of lives and situations.”

High history sits in every word, even in the ‘x’ of a single kiss. Or the words in the postcard below; prices for Train, Ale and Fags.

A postcard too is often the physical trace of a journey, one connecting the dots from the place in which it was posted to its final destination. But this destination’s never really reached, and as such, a conversation which may have begun 100 years ago, is never finished. We read the words today, written before we’d ever the hope of existing, sent by those who don’t exist anymore.

The images in this exhibition are not ‘genuine’ postcards per se, but they are (for the most part) postcard-sized, inspired by a collection dating from the First World War. It’s the idea of the part (the individual image) as being a part of a whole which interests me and the whole being immanent in the part, just as humanity is immanent in every individual.

Echo

Last week I installed a temporary artwork in St. Giles, Oxford entitled Echo. The piece comprised approximately 200 photographs of individuals isolated from group shots of the fair taken in 1908, 1913 and 1914. The date of the exhibition, Wednesday 9th September was important in that it was the day after St. Giles’ Fair was taken down, and the ‘space’ left in its wake (the fair was up for two days and filled the entire street) helped frame the fact that all those people shown in the exhibition, who had once stood in the same street, had, like the fair, gone. I was interested in the boundary between existence and non-existence, the impossiblity – within the human mind – of death as nothing and forever. What I hoped the photographs conveyed was the importance of having been.

The installation required grass in order that I could place the markers in the ground and the War Memorial in St. Giles was the only viable option. What was particularly interesting was how the location altered the meaning of the work in that one couldn’t help identify the people with the memorial and in particular those who fell in World War One. Given that some of the men pictured in the photographs almost certainly went to war and may well have lost their lives, so the work took on a new and poignant dimension. Many of the women would have lost husbands, brothers, fathers, uncles and so on.

Click here to read more about this exhibition.

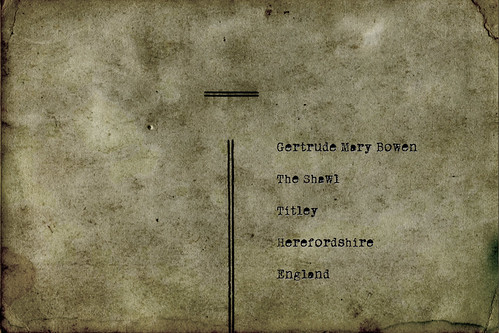

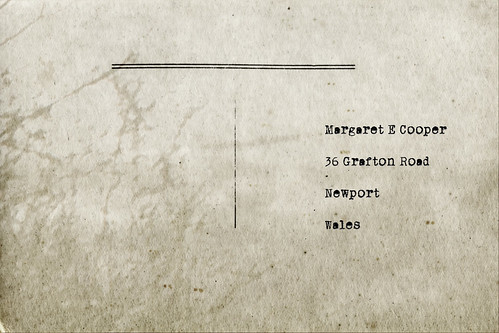

Front and Back Battlefield

Below are examples of the postcards I have made featuring the names and addresses of next-of-kin of men of the 2nd Monmouthshire Battalion who fell in the Fisrt World War. I’m making the work for a conference in Tourist Experiences: Meanings, Motivations, Behaviours at UCLa in April. The first image shows the postcards in their entirety.

Front and Back (2nd Mons)

I started work on a new painting today based on the work I made as part of my Mine the Mountain exhibition. This piece, Front and Back (2nd Mons), uses the ‘T’ shaped divides on the backs of postcards which are then stencilled onto the canvas, already painted with a generic battlefield scene. I would really like to paint this on a large scale but we’ll see how this goes first.