In my last post I talked about entropy, in particular with reference to a book I’ve recently re-read by Carlo Rovelli called ‘The Order of Time’. I ended with the question (one as much for myself as anyone else); what has this got to do with my work?

So, here goes with (the beginnings of) an answer.

As I’ve said, my work has often sought to imagine past moments as if they are ‘now’ in order to better empathise with those who lived at the time; in particular those who lived through traumatic events.

Borrowing from the world of physics and what I’ve gleaned about entropy, I can look at a past moment as something which has a very low entropy (and here, of course, I’m using these terms in a loose, ‘poetic’ way rather than anything scientific). The past is like the sandcastle as opposed to the pile of sand (but with far fewer possible configurations of state than the castle).

This is because the past moment has happened and therefore its form is fixed; there are no different configurations by which it can enter the next moment as the next moment has also already happened. If we think of the moment we are living now, then we can think of it as having very high entropy as there are countless possible configurations by which we, as people living in this particular moment, can enter the next and so on. We are like the pile of sand as opposed to the castle.

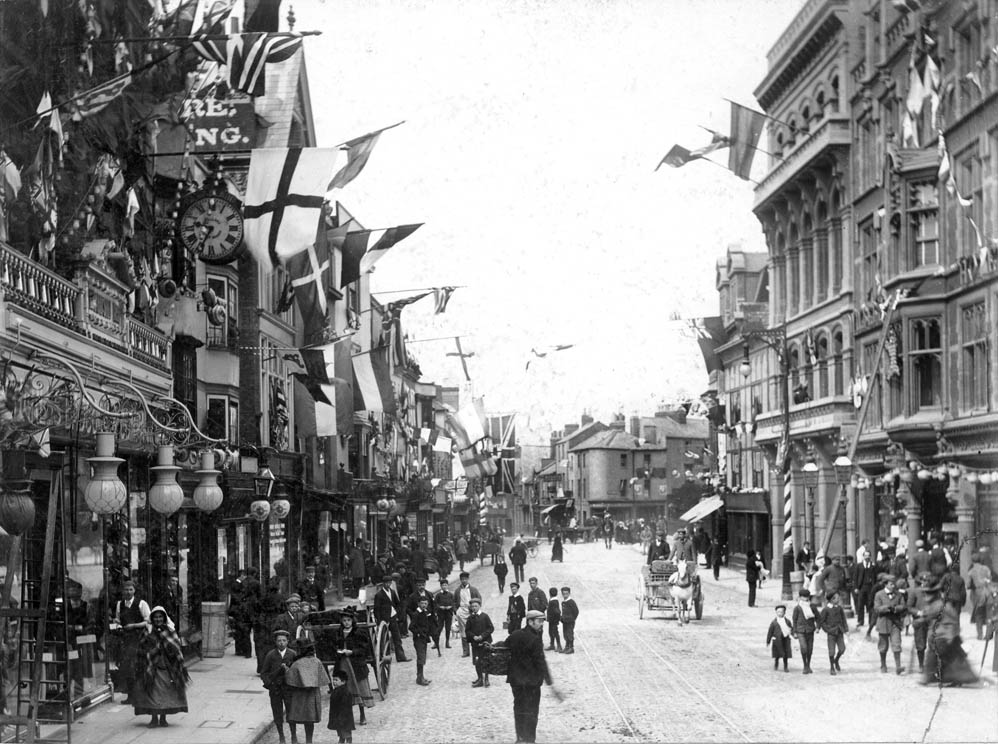

Below is a photograph taken in Oxford in 1897 to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubliee.

I want to look at this photograph as being illustrative of a moment in time rather than as an object in its own right. So what do we see?

If we are going to try and recreate a past moment, we have to try and think of that moment as it happens, not as it was. So, when I look at an image like this, at a moment frozen in time 125 years ago, I try to imagine the scene just before the image was taken and for a short while after. To do that, I might zoom in on a detail – one of the people – and imagine them moving. I imagine the noise of the scene, the sounds they might have heard and think about what they might have been saying (if anything).

It’s easy to animate the faces above, but to animate the moment, I have to zoom out a little, to catch more of the scene around them. If we look at the boy in the first image for example, we can see that he is standing with a girl and a small boy. The girl is clearly talking to him but his eyes are on the camera. The small boy beside her looks impatient as if he wants to be doing something else.

And we can continue to zoom out and allow more of the moment to reveal itself.

One thing I do find with photographs like this, is that it’s often those people who are in the background and who are completely oblivious to the picture being taken that allow me to animate the scene. For example, this man (below) up a ladder adjusting the bunting.

One can imagine him working and the effort he is making and the fact he’s unaware that he is part of the picture allows me to reach beyond the edges of the photograph. It’s as if, through his being unaware of the photograph, the boundaries of the photograph are dissolved and the moment is given rein to move (a piece I made as part of my MA several years ago – Creatures – is concerned with this very idea).

But what has this all got to do with entropy?

The present moment has ‘high entropy’ in that the number of possible configurations (the different configurations that our blurred vision does not distinguish between) which will take this moment into the next are vast. But for a past moment, such as the one above, the number is practically zero, in that the moment has come and gone. It’s ‘entropy’ is very low. So if we are to try and imagine this moment in 1897 as if it’s now, we have to ‘disorder time’ and imagine the scene as if its ‘entropy’ is as high as he moment in which we now exist.

In a post from several years ago (Windows, Bicycles and Catastrophe) I talked about these background details and how they can help bring a past moment to life.

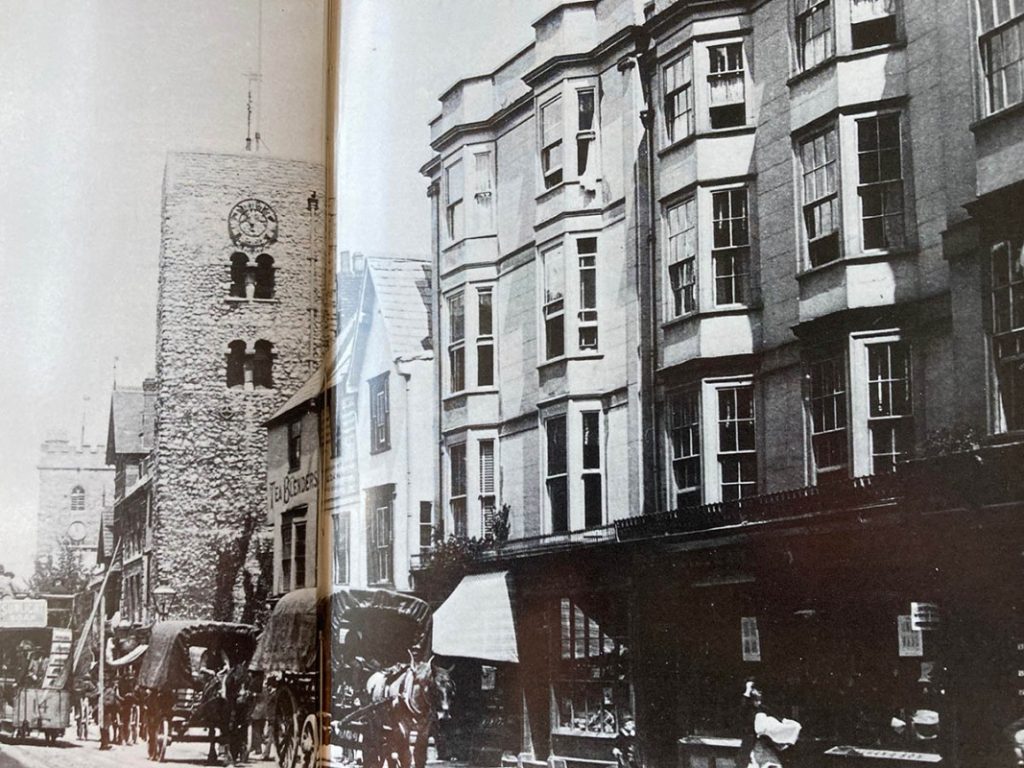

In the picture above, the horses and carts locate the photograph in the early 1900s but it’s the windows – the open windows – which help me locate myself in the time. Why? Because the rooms behind the windows are spaces outside the photograph; spaces oblivious to the photograph being taken. It’s as if they have escaped the moment frozen by the camera. The open windows also speak of a time before the photograph was taken and therefore give the photograph a sense of duration which, like the rooms behind them, also extend the boundaries of the image. When the photographer took the photo, the windows had been open a while beforehand; people had (obviously) opened them and I can begin to imagine those moments. I can imagine being in one of those rooms, looking out through the open window and seeing the horses down on the street and hearing the sounds of the city. These open windows therefore can help us see the past moment as it happens rather than as it was. They ascribe the picture a duration and give it flow.

In his book, The Order of Time, Carlo Rovelli writes: “The growth of entropy itself happens to open new doors through which entropy can increase further.” In the case of this image, Rovelli’s doors are our windows but the effect is the same. We begin to disorder time and locate among these details, pockets of potential. Instead of everything being fixed, there is room for manoeuvre, for change; entropy increases.

As I wrote in my previous post: …our blurred view of the world equates to our recognition of things as things; objects with form, and it’s because of this that we experience the flow of time; the sandcastle collapsing on the beach and the castle falling slowly to ruin.

This blurring is the term used to describe how we perceive the world. We see things as particular (things as things; objects with form as opposed to how they are at the microscopic level). Rovelli writes: “The notion of particularity is born only at the moment we begin to see the universe in a blurred and approximate way. Boltzmann has shown that entropy exists because we describe the world in a blurred fashion. He has demonstrated that entropy is precisely the quantity that counts how many are the different configurations that our blurred vision does not distinguish between.”

In the case of the past itself and our view of it, our ‘blurred view’ is that of the object, the photograph, the relic. It is the knowledge we derive from sources; diaries, letters etc.

Rovelli continues: “The difference between past and future is deeply linked to this blurring. So, if I could take into account all the details of the exact, microscopic state of the world, would the characteristic aspects of the flowing of time disappear? Yes. If I observe the microscopic state of things, then the difference between past and future vanishes.”

A quote from William Blake is pertinent to this point: “If the doors to perception were cleansed, then everything would appear to man as it is – infinite.”

If then, we imagine the entirety of the past as being akin to the world at the microscopic level, then as we look beyond what our blurred vision allows us to see of the past (beyond the relics and artefacts) and see the details (for example, the rooms beyond the windows), then, just as at the microscopic level, where the difference between past and future collapses, so it does when we focus our attention on those seemingly insignificant details; details which we might well experience in our own, everyday lives.

One aspect I want to return to is the flow of time. As I wrote above: “These open windows therefore help us see the past moment as it happens rather than as it was. They ascribe the picture a duration and give it flow.” But this will have to wait for my next post.